10 Characteristics That Define Gen Z (Part II)

And 10 Startups Building on Them

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Hey Everyone 👋 ,

Tomorrow we’re hosting the inaugural Index Gaming Summit. As I’ve written about in Digital Native, gaming is the largest media category (~$200B in revenue, bigger than the music + box office + streaming video industries combined) and the most underrated. In our cultural imagination, we still think of a gamer as an antisocial teenage boy in his mom’s basement. But that stereotype couldn’t be more wrong: the average age of a U.S. gamer is 35, 45% of gamers are women, and gaming is inherently social. Nearly 1 in 2 people on the planet (about 3.5 billion) play video games.

During the Summit, we’ll hear from leaders across the Index gaming portfolio—Roblox, Discord, King, Supercell, Dream Games, Rec Room, and more.

The Summit is free, virtual, and open to everyone—you can register here 🎟

Hope to see you there! 🎮

With that, on to this week’s piece—Part II of examining Gen Z characteristics.

10 Characteristics That Define Gen Z (Part II)

Last week, I opened with a George Orwell quote: “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” The idea was that Gen Z is changing the world around us in real-time, and that observing change as it happens requires concerted effort.

The new generation is redefining how people transact and interact online. There are already big businesses that have become effectively synonymous with Gen Z: SHEIN and Depop, Roblox and BeReal, even Notion in some ways.

But first and foremost, of course, is TikTok—and TikTok is eating the world. From a piece in Bloomberg this week:

More time is now spent on TikTok than on Facebook and Instagram combined. Three years after turning on ads, TikTok will do more in ad revenue this year than Twitter and Snap combined. And the cost for a one-day run of a TopView ad (an ad that the TikTok app opens directly into) has swelled 4x year-over-year to $2.6M.

The sheer scale of Gen Z-dominated apps speaks to the size of the opportunity—and Gen Z is already the U.S.’s largest generation, with 86 million Gen Zs to 82 million Millennials. The generation will dominate commerce and consumer social for decades to come.

In Part I last week, I dug into five generational characteristics and examined one company building in each:

This week, I’ll dig into five more characteristics:

👚 Thrifty

🤲 Sharing

🌱 Impactful

📈 Investing

🪐 Escapist

As with last week, the goal here is to explore how change is happening in real-time—right in front of our noses.

👚 Thrifty

One of the most stunning success stories of the past few years has been the rise of SHEIN. SHEIN, a Chinese company founded in 2008, came out of nowhere to become America’s largest fast-fashion retailer:

SHEIN has grown over 100% every year for eight straight years, and its latest private market valuation makes it worth more than Zara and H&M combined. Last month, SHEIN dethroned Amazon as the No. 1 shopping app in the iOS and Android app stores.

SHEIN’s velocity is something to behold: 8,000 new items are added to SHEIN every day, while Zara adds 500 every week. SHEIN is basically an internet-native reincarnation of Zara and H&M, leveraging better technology to squeeze three week design-to-production timelines into three days. SHEIN combs competitor’s websites and Google Trends to figure out what’s in style, then creates designs quickly, forecasts demand, and adjusts inventory in real-time.

SHEIN’s speed and ease (the company is 100% e-commerce) has led to an ultra-consumerist culture in which customers often buy clothes from SHEIN multiple times a week. A phenomenon called a SHEIN “haul” has emerged on social media, in which influencers buy $500+ of SHEIN clothing for try-on videos. (SHEIN hauls, mostly on TikTok, are reminiscent of Forever 21 hauls on early YouTube.)

One of the most interesting Gen Z contradictions is the generation’s simultaneous concern for the environment and penchant for ultra-fast-fashion. In a survey from Wharton, 75% of Gen Zs said that a brand’s sustainability is important when making a purchase. And yet, Gen Z is powering SHEIN’s explosion. What gives?

My take is that consumers do care about the environment—but they also care about a good deal. And the latter often trumps the former in the ranking of priorities.

🤲 Sharing

The rise of SHEIN and ultra-fast-fashion has in turn fueled the resale economy. Guilt from participating in the consumerist culture outlined above—buying clothes two, three, four times a week—can be partly assuaged by reselling what you buy. And in a world in which every outfit finds its way to your Instagram grid, people are less keen to repeat what they wear; they would rather follow the endless cycle of buy, sell secondhand, buy, sell secondhand.

Secondhand fashion is one of the fastest-growing but least-talked-about industries. Resale is a $40B market expected to double to ~$80B by 2025 and to triple to ~$120B by 2030. About a quarter of the secondhand market is apparel, which will grow 40% per year through 2025. In 2019, secondhand apparel grew 21x faster than traditional apparel and in 2020, 36 million Americans sold items secondhand for the first time. By 2030, the secondhand fashion industry will be nearly twice the size of the fast fashion industry.

I’ve written in the past about Bella McFadden, a professional reseller on Depop, a secondhand clothing marketplace popular among Gen Zs (90% of Depop users are under 26). Last year, McFadden became the first person to make over $1 million selling on Depop. She’s now sold 64,205 items (!) through her Depop store, which has 380,000 followers.

Gen Z celebrities also embrace resale culture. Olivia Rodrigo has been called “the first Poshmark pop star,” with one fan saying: “I definitely think she gives that cool friend kind of vibe—she still goes to smaller thrift shops and that’s very relatable.” Rodrigo even sells her clothes on her own Depop store with an average price of ~$30.

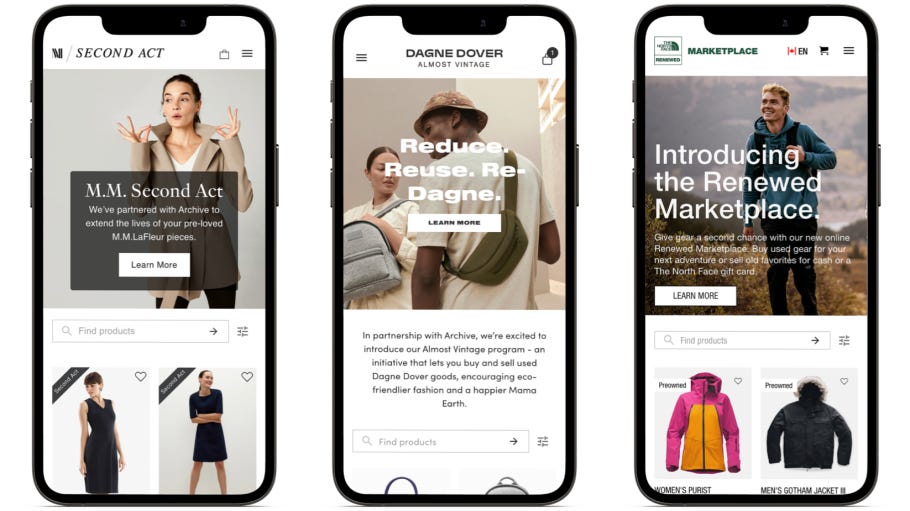

New startups are making it possible for brands to own their own secondhand. Archive, for instance, builds white-labeled peer-to-peer marketplaces on the websites of brands like North Face, Oscar de la Renta, and Cuyana. Brands get to control their brand’s resale experience, flex their focus on sustainability, and capture more thrifty, cost-conscious consumers.

Another growing trend is resale at checkout. Reminding consumers of the opportunity to resell down the road increases conversion to buy and lifts AOV (average order value). I’m furnishing a new apartment right now. I’m more willing to splurge on that expensive coffee table from Restoration Hardware if RH tells me, “Resell this $3,000 table for $2,000 in three years.” From the consumer mindset, price becomes less of an issue and friction to buy goes down; I might even think, “I just saved $2,000 so let me go buy new dining chairs!”

We’ll see more brands control the resale experience and lean on resale to drive conversion. We’ll also see more vertical solutions emerge. Facebook Marketplace has quietly become the second-largest marketplace in the world by number of monthly active users, second only to Amazon. The success of Marketplace (which now seems to be the part of the Facebook app stemming churn) speaks to the opportunity for secondhand. The unbundling of Facebook Marketplace is the new unbundling of Ebay.

🌱 Impactful

A key driver of secondhand is the environmental component. The fashion industry contributes 8% of greenhouse gas emissions; fast-fashion is a particular culprit.

This speaks to an adjacent, broader trend: impactful commerce. Young consumers want to shop with brands that align with their values. We see this sentiment in how today’s breakout brands are values-driven: Allbirds and Everlane are built around sustainability; Bombas and Warby Parker use “buy-one-give-one” business models. And we see this sentiment in the success of brands that take a stand—Nike’s Colin Kaepernick ad campaign comes to mind. (Nike consistently ranks #1 for Gen Z’s favorite brand.) In consumers’ eyes, if you don’t stand for something, you don’t stand for anything.

I wrote earlier this year about our investment in Beam, which is building the infrastructure for impactful commerce. At checkout, Beam gives you the option to contribute a percentage of your cart size—typically 1%—to a non-profit. Here’s a nifty GIF to show how selecting a non-profit at checkout looks in motion:

Importantly, it isn’t me that’s paying—it’s the brand. Why are brands willing to give up 1% of revenue? For one, brands are able to put their money where their mouth is when it comes to the causes they champion. Communicating these values creates customer loyalty. But more tangibly, brands see real ROI: AOV goes up meaningfully; cart abandonment rates go down; shoppers become more likely to become repeat customers.

I expect this form of impactful commerce to become tablestakes. In 2022, people—and especially Gen Zs—expect to shop their values.

📈 Investing

Last year’s meme stock craze feels like a long time ago. It might be (rightfully) remembered as an emblem of 2021 market exuberance, but it should also be remembered as the moment when Gen Z cemented itself as the investing generation.

A key fact underpinning inequality is that millions of Americans don’t own stock. Only about 1 in 2 Americans have any sure to the stock market (including retirement plans), and that exposure is stratified by income: only 15% of families in the bottom 20% of income earners hold stock, while 92% of families in the top 10% of the income distribution own stock. The top 10% of income earners own 10 times as much of the stock market as the bottom 60%, and white investors own 3x as much stock as Black or Hispanic stockholders.

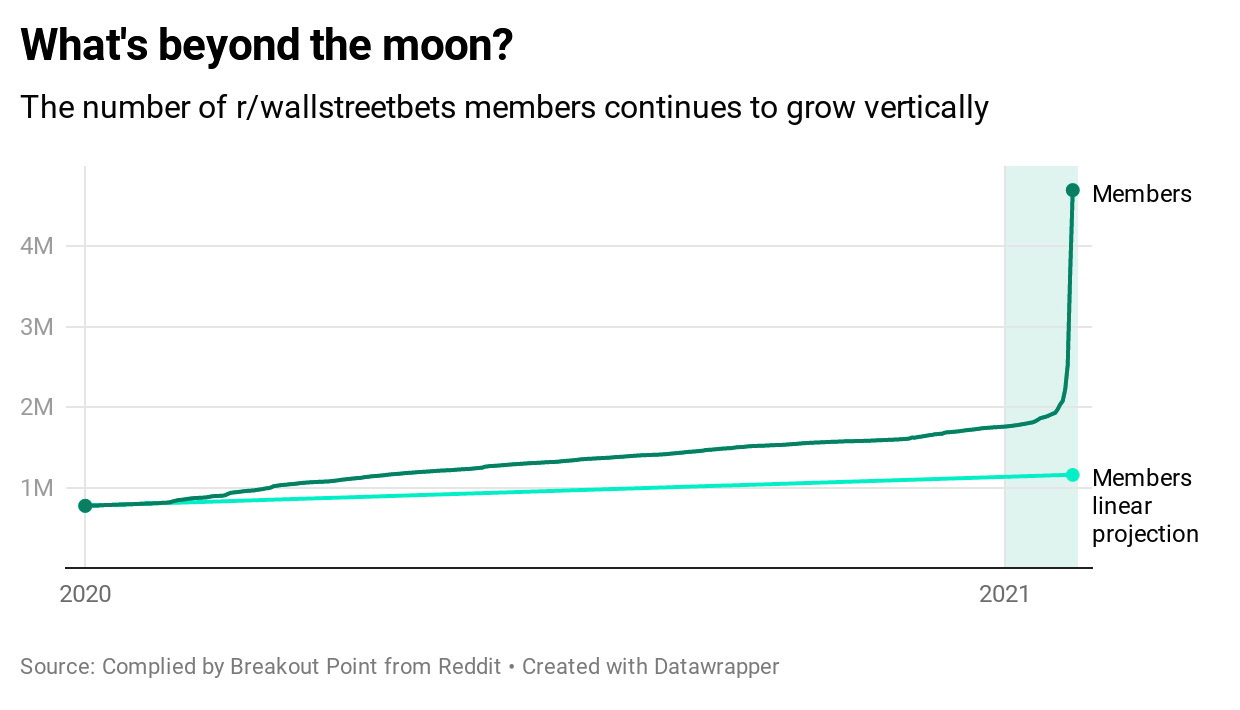

The rise of Robinhood and r/WallStreetBets has happened alongside the rise of a populist, stick-it-to-the-man ethos. The meme stock craze showed that.

But there’s a more fundamental mentality shift at play—the shift to thinking like an owner, of rejecting the idea of renting time to a corporation for 50 years. We see new platforms underpinning this shift: Masterworks lets you invest in fine art; Rally lets you invest in people; Alt lets you invest in sports cards. The value proposition is that you can get exposure to a new asset class to build wealth.

What’s also interesting about the investing movement is that it’s become a social phenomenon. Just look at r/WallStreetBets’s 12.2 million members. Investing is about community. Companies like Dub lean into the social side of investing, letting you swap ideas with other investors and even “dub” someone to mimic their portfolio construction. The aspiration is to democratize knowledge and to build in community support.

If the 20th century version of investing was confusing, inaccessible, and solitary—e.g., a wealthy businessman hiring a stockbroker—the 21st century version of investing is convenient, communal, and open to everyone.

🪐 Escapist

In Ready Player One, the analog world is crumbling, and people retreat to the metaverse-like OASIS to entertain themselves. The OASIS is an escape.

In our modern world, young people likewise use technology to escape. Binge-watching Netflix, endlessly scrolling TikTok, going down late-night YouTube rabbit holes. The internet provides refuge. (The irony, of course, is that often people are seeking refuge from the toxic sides of technology. Escapism is closely related to stress and anxiety, characteristics covered in last week’s piece.)

The playwright George Bernard Shaw once said, “Without art, the crudeness of reality would make the world unbearable.” You could extend his words to entertainment: for many, life would be significantly less bearable sans movies and TV and books. Think of the meaning that the world’s enduring IP franchises inject into people’s day-to-day lives. (I know my life would be dimmer without Star Wars.)

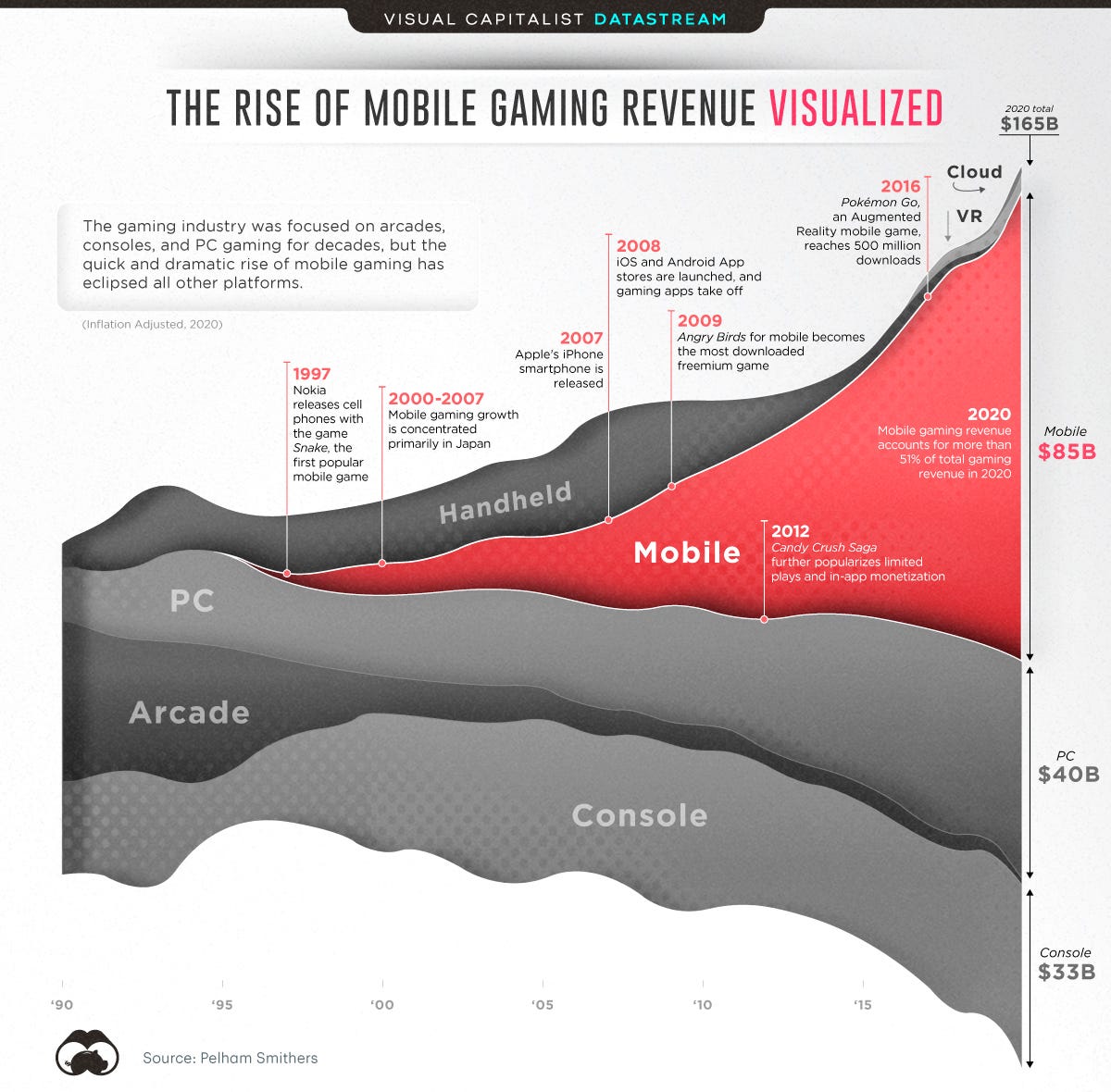

When I think of escape, I think of one category in particular—gaming. And I especially think of mobile gaming, which has exploded over the past decade.

How many people have escaped the world for hours on end with Candy Crush?

And new companies like Dream Games (one of our investments at Index) are creating new iconic franchises for entertainment and escape: Dream’s Royal Match is one of the fastest-growing games in history.

This is where I again plug tomorrow’s Index Gaming Summit, where the founder of Dream Games, Soner Aydemir, will be speaking 😁 RSVP here.

One other interesting trend has been the rise of hypercasual games—games with ultrasimple gameplay. Take, for example, Fill the Fridge (stocking a fridge) or Acrylic Nails (painting nails). Hypercasual games often incorporate ASMR (e.g., popping bubble wrap), another escapist and pleasure-centric phenomenon. Hypercasual game downloads surged to 15.6 billion last year, up from 12.6 billion in 2020 and 7.5 billion in 2019, and Zynga recently bought a stake in hypercasual game studio Rollic for $180M.

Hypercasual games are a form of comfort food—they provide mindless and enjoyable escape at a time when people need it most.

💭 Bonus: Nostalgic

In response to last week’s piece, my friend Eric made an interesting point: arguably more compelling than Gen Z characteristics are Gen Z contradictions. And chief among contradictions is Gen Z’s nostalgia for the 90s and the aughts.

Why, for instance, are Friends re-runs more popular among teenagers than the hundreds of new shows on streaming services? Why are wired headphones back in vogue when AirPods exist? In an age of Spotify, why are vinyl sales exploding?

Part of nostalgia is pandemic-fueled: nostalgia is a source of comfort during difficult times. (The need for comfort has only increased in 2022 with Ukraine, gun violence, Roe v. Wade overturned, and more.) TikTok is full of videos reminiscing on the small comforts of yesteryear, and this is very much a Millennial phenomenon too.

But part of nostalgia also stems from the pervasiveness and intrusiveness of tech, which makes young people long for an analog world. Today’s tech-dominated world gives older technologies, like vinyl, a certain romanticism. The idea of a world pre-iPhone (which came out exactly 15 years ago today) sounds downright utopian.

Many Gen Z characteristics intersect and build on one another. Stress and anxiety beget the need for escapism. Thriftiness fuels secondhand, which in turn is built on impactful commerce. The investing generation goes hand-in-hand with entrepreneurship. Many of these traits can also be found in Millennials, and many will be found—perhaps moreso—in Gen Alphas, the oldest of whom are 12 (three years younger than the iPhone). Behavior shifts influence capitalism and commerce and culture. We can do our best to examine these shifts and predict their ripple effects, but ultimately we’ll have to just wait and find out.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: