3D Content and the Floodgates of Production

A Framework for Tectonic Shifts in Technology

Weekly writing about how technology shapes humanity, and vice versa. If you haven’t subscribed, join 45,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

3D Content and the Floodgates of Production

When I think about changes in technology and culture, I think about the Earth’s tectonic plates shifting. We don’t feel the Earth move—we don’t even think about it—but we’re constantly in motion.

Innovation is similar: for the most part, we don’t feel small day-to-day movements. There’s the occasional earthquake, yes—ChatGPT being released, for instance, or the iPhone coming out. But most innovation is subtle, compounding over months and years into more obvious changes.

When we pause to look back, it becomes clear how far we’ve come. The world has changed radically since the supercontinent Pangaea existed 200 million years ago (throwback to 7th-grade science), but those changes were gradual: most tectonic plates only move three inches a year.

It’s a similar story in technology. My dad grew up with three TV channels. Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web when most Boomers were well into their 30s, and mobile took off another two decades later. Only recently have we been able to search the world’s information (Google), connect with friends across the world (Facebook), and get nearly anything delivered to our door in two days (Amazon). We don’t feel the day-to-day changes, but society has evolved rapidly in 50 years.

What interest me now are new tectonic shifts—major shifts in technology and human behavior that will change how we live. These are decades-long shifts that we’re in the midst of. For this week’s piece, I chose three interrelated shifts:

The march towards ever-more-immersive content,

The gamification of everything, and

The opening floodgates of production.

Let’s dig into each one.

3D Immersive Content

In a recent presentation, students at the Parsons School of Design showcased the outfits they’d designed during the semester. The catch: the outfits were entirely virtual, designed to be worn in Roblox.

The presentation was the culmination of a 16-week course that Parsons created in collaboration with Roblox. The goal for students was to master a potentially-important future category of fashion, digital fashion; the goal for Roblox was to teach designers how to participate in its robust digital economy, and to age up its userbase.

Digital economies have become massive. Roblox developers earned over $600M in 2022, a payout that’s grown at a 77% compound annual growth rate since 2019. Epic Games, the maker of Fortnite, grossed nearly $50M just from sales of NFL skins.

One tectonic shift is the steady migration to ever-more-immersive content formats.

We saw this offline, with books giving way to radio, which in turn gave way to film and television. And we’ve seen the pattern repeat online: Twitter was text-based; Instagram popularized photo-sharing; TikTok is built around video. Now, every platform is scrambling to be video-first. Each major platform gets progressively more immersive.

The inevitable next step is three-dimensional content. This is an if, not a when. Young people are already spending enormous amounts of time in Roblox. In last week’s piece about Duolingo’s TikTok strategy, we talked about how much time young people spend on TikTok, yet Roblox engagement is even more impressive: while TikTok is running circles around YouTube in daily engagement (113 minutes per day vs. 77 minutes per day, for daily actives), Roblox trumps them both at a staggering 190 minutes per day. That figure is up +90% since 2020. (Roblox still skews young, with 50% of users 12 or under.)

Virtual reality and augmented reality have been hyped for years, prematurely, but they’re coming. When they arrive, we’ll realize that the hype wasn’t unwarranted, just early. (One of my favorite quotes in the startup world: being early and being wrong often feel the same.) I like how Tim Sweeney, the founder of Epic Games, once put it: “I’ve never met a skeptic of VR who has tried it.”

People prefer content that’s more immersive and more engaging; we’re just waiting on technology to catch up. And we may finally be getting somewhere. Apple is about to release its highly-anticipated mixed reality headset, which is expected to cost around $3,000 and to resemble a pair of ski goggles.

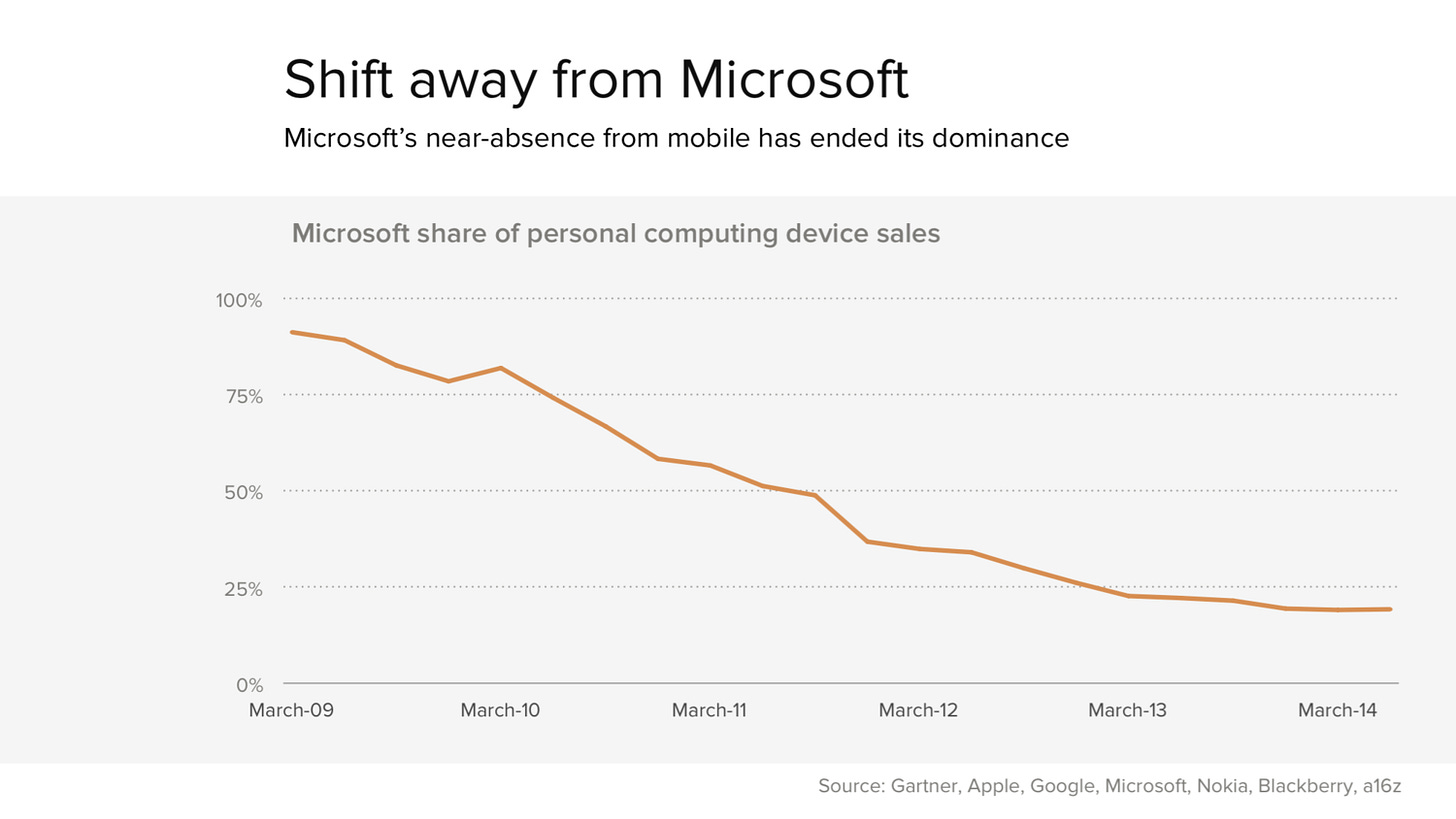

The size of the opportunity here has everyone scrambling. Meta is spending $10 billion a year on its Reality Labs division, and continues to double down on Oculus. Google, apparently not scarred by its Google Glass debacle, is building its own mixed reality headset. Microsoft, for its part, has invested heavily in HoloLens, determined to not repeat what happened with mobile. When a company misses a platform shift, the entire company becomes at risk:

What headsets need, of course, are killer applications. Gaming applications will come first, but others will follow: education, productivity, socialization. In 10 years, I don’t see us still using a tiny black rectangle of glass as our portal to the internet. We’ve seen early mobile AR applications—Pokemon GO remains the most mainstream use ($5B in lifetime revenue), and Snap says that 250M users engage with AR filters every day. But we’ll soon move beyond our phones—headsets, then glasses, then potentially even contact lenses. The killer applications will be native to these new products.

On the behavioral side, it’s interesting to see how users mimic the real-world in 3D immersive worlds. One student from the Parsons course, Yoshe Li, told The Verge:

“It’s funny that when it rains [in Animal Crossing], we just go home and change into raincoats,” Li says of playing Animal Crossing. “That’s very similar to when I was playing Roblox with my friends. We went to this game scene, and we changed clothing that matches that game scene. And we go to that one, and then we have to like change for that.”

Just as different contexts in the real world warrant different outfits, so do different contexts in virtual spaces. An avatar can’t get wet, of course, but that doesn’t matter—the same “rules” apply. When Animal Crossing blew up during the pandemic (the game broke Nintendo’s first-year sales record), people brought their offline lives into the game. Some users even put up Biden-Harris signs in their front yards:

Two years ago, in May 2021, I wrote about the Proteus Effect. The Proteus Effect is the phenomenon that our behaviors within virtual worlds are influenced by the characteristics of our avatar. Stanford’s Jeremy Bailenson and Nick Yee are the leading researchers on the Proteus Effect. In their seminal study, they showed that both an avatar’s attractiveness level and height influenced behavior:

Participants assigned to more attractive avatars were more intimate and open with other participants. They both stood closer (virtually) to other participants and disclosed more about themselves.

Participants assigned to a taller avatar behaved more confidently in a negotiation task and showed more assertive, dominant behaviors.

Bailenson and Yee later tested whether these online identities translated to offline interactions. They did. Bailenson and Yee wrote: “In addition to causing a behavioral difference within the virtual environment, we found that participants given taller avatars negotiated more aggressively in subsequent face-to-face interactions than participants given shorter avatars.”

In the 1970s, researchers showed that people’s clothing can affect behavior. Wearing a lab coat and holding a clipboard, for instance, make doctors more decisive and effective. Candidates who wear professional attire to job interviews perform better. But digital worlds magnify these effects. As Bailenson and Yee put it: “In online environments, the avatar is not simply a uniform that is worn—the avatar is our entire self-representation.”

The Proteus Effect is named for the Greek god Proteus, who could shape shift into whatever form he pleased. Digital worlds give us Proteus-like powers: the ability to rapidly and dramatically change our likeness at unprecedented speed and scale. As we spend more time as avatars, particularly within VR, the Proteus Effect will become more fundamental to how we communicate and interact.

Three-dimensional, immersive digital worlds are about to usher in new consumer behaviors. The combination of new technology and new behaviors reliably leads to large new companies. I expect that the next social network will look more like Minecraft or Roblox than Instagram or Twitter, and that categories from gaming to collaboration software will eventually be reinvented by VR/AR. We may still be a few years away from true consumer adoption, but the shift to more immersive content formats is decades in the making; we already know what comes next, and it’s just a question of timing.

The Gamification of Everything

Our attention spans are deteriorating—rapidly.

A study from Microsoft found that since the year 2000, the average human attention span has decreased from 12 seconds to 8 seconds—a 33% drop. This means that humans now have shorter attention spans than goldfish. Yikes.

In case you forgot, we were talking about our shortening attention spans. This shortening is the result of having constant, unfettered access to the world’s information, content, and communications.

The average American touches their phone 2,617 per day and unlocks it 150 times. TikTok popularized short-form video, bite-sized pieces of content that we flip through endlessly; if a video fails to capture our attention in the first few seconds, we swipe to the next. Many young people can’t sit through an hour-long TV show without being on their phones. As the joke goes, “I’m going to take a break from working on my medium-sized screen to go watch my big screen while I scroll my tiny screen.”

As more content vies for our attention, everything will become gamified. I view this as a long-gestating shift that we’re in the middle of. Time and money are scarce resources, and companies are in a battle to capture both. The result will be gamified experiences that aim to engage and retain users.

In 2010, Chris Dixon wrote a piece that famously declared, “The next big thing will start out looking like a toy.” He was right. YouTube was dismissed as “cat videos” before it swelled to 2.7B monthly active users. TikTok was dismissed as a lipsyncing app before vacuuming up nearly two hours of its daily active users’ time each day.

The next iteration of Dixon’s statement could be, “The next big thing will feel like a game.” And it will be true across every sector. As digital content becomes more infinite, consumer experiences feel asymptotically more game-like:

We see this in products today: key features like leaderboards and streaks are built around gamification principles. Strava uses leaderboards to encourage its users to work out; Duolingo uses streaks (popularized by Snapchat to gamify socialization) to encourage users to complete language-learning exercises every day. Even driving an Uber or Lyft can feel like a game: Uber uses “quests” to nudge drivers to work longer hours, and Lyft offers “streak bonuses” for drivers who accept back-to-back rides.

We’ve seen some apps pare back gamification. Robinhood got rid of its confetti celebrations after being criticized for gamifying investing. Its new celebratory product design is more restrained:

A more recent example of gamification is Temu, which has topped the App Store for most of the past six months. Backed by the Chinese internet giant Pinduoduo, Temu gamifies shopping: users can invite friends to get discounts; spin a roulette wheel to collect prizes; and even win cash prizes by collecting fish in a game 🐠

“Social shopping” has been a massive category in China for years—Pinduoduo has a $95B market cap and counts 751M monthly active users—but the category is relatively nascent in the West. Pinduoduo hopes to change that with Temu, plowing money behind aggressive user acquisition and gamifying the discount shopping experience.

In many ways, gamification can be a good thing: when done right, dull experiences like working out or language learning become fun and engaging. On the more sinister side, it’s easy to imagine fields like healthcare and financial services becoming overly-gamified in a capitalistic quest for profit. Companies and governments will need to put the proper guardrails in place. But the gamification trend isn’t going away; it’s becoming a necessity for companies competing in a world of near-infinite content and ever-diminishing attention spans.

Opening the Floodgates of Production

The internet exploded the floodgates of distribution. I expect generative AI to explode the floodgates of production.

Every product needs 1) to be created, and 2) to find its way into the hands of customers. What made the internet so groundbreaking was how it reinvented #2.

We used to have go through gatekeepers of culture—the film studio executive; the newspaper editor-in-chief; the publishing house. Gatekeepers controlled who saw what content, when, and where; gatekeepers were the arbiters of culture. Online, though, anyone could get in front of anyone. Authors could self-publish, YouTubers became more popular than late-night talk show hosts, and we saw the rise of the creator class.

Technology has also seeped into production, of course—tools ranging from Figma to Canva, Veed to Descript have made the creation process easier. CapCut, the Bytedance-owned editing app behind many TikTok trends, was quietly the 4th-most-downloaded app in the world last year (357M downloads), slotting between #3 WhatsApp (424M) and #5 Snapchat (330M).

But three decades into the digital age, barriers to production remain stubbornly high, particularly when compared to barriers to distribution. That’s now changing with generative AI.

Generative AI tools give anyone creative superpowers. In seconds, Midjourney delivers me this image from the prompt “Tectonic plates colliding, viewed from space, black and white, photorealistic and 4K”—

As someone with precisely zero artistic talent, I could never have produced a visual like that without AI’s help.

Runway brings similar creation abilities to video—anyone can intuitively create and edit high-quality video. Here’s a GIF showing a user make a cityscape more cinematic, then edit out a lamppost.

The visual effects team on Everything Everywhere All At Once, the most recent Best Picture winner, used Runway on the film. It’s one reason that the movie was able to be made with just seven people (five full-time, two contracted) on the VFX team.

On June 16th, Pixar’s new film Elemental will be released. The story is classic Pixar: it takes place in Element City, a land where Fire, Water, Land, and Air residents live together. The city is segregated into element-specific neighborhoods, and our protagonists Ember (Fire element) and Wade (Water element) prove that different elements can be friends. The film is a very on-the-nose allegory for race relations.

Pixar spent $200M making Elemental, with a ~1,000-person army of animators, writers, and actors assembling the finished product.

But imagine if anyone could create a high-fidelity animated film. In five years, you or I might be able to come up with an idea for a Pixar film and feed that idea into ChatGPT to produce a script. We might then feed that script into a new text-to-film tool that spits out a fully-rendered Pixar-quality film. That entire process might take minutes.

I can already do some of this today. My friend Justine posted over the weekend about playing around with AI tools to make herself into a Pixar character. I took her up on the challenge and made my own version.

Following Justine’s instructions, I first uploaded photos of myself to Midjourney, then added the prompt, “Male Pixar character, blond-brown hair and green eyes.” Here’s what Midjourney delivered:

A bit more Disney Animation than Pixar, but not bad. I then uploaded the image into HeyGen, wrote a short script, and turned it into a video. Here’s the final product. Unfortunately I can’t include sound on Substack, but you get the gist:

The entire process took less than five minutes, and was entirely free. Pretty cool.

A talented writer or animator, of course, will still have an edge in the quality of the Pixar film they can produce. Pixar itself probably isn’t going anywhere. But barriers to creation are falling dramatically. Anyone with a good enough idea can produce something exceptional. We used to be required to speak the language of creative tools, which required specialized knowledge; now, creative tools speak our language, responding to text prompts.

When you think like this, NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang’s prediction sounds more likely: “Every single pixel will be generated soon. Not rendered: generated.”

Final Thoughts

To summarize the three tectonic shifts:

Technology follows a reliable march to more immersive content formats.

The more content out there, the more products become gamified.

Over time, the arc of creative tools bends towards being more accessible—and generative AI will fling open the floodgates of production.

These are “rules of the universe” that I view as near-indisputable. They help guide my thinking on the progression we’ve seen with technology, and what’s yet to come. There have already been large companies built along these shifts, and each shift has the potential to underpin future value creation. For example:

What will be the platform for augmented reality or virtual reality content? It’s unlikely to be Instagram or TikTok; new content formats typically usher in de novo platforms.

Some parts of our lives remain mundane and unenjoyable—how can they be gamified in ways that incentivize good behaviors, and how can we curb “over-gamification” tendencies?

What happens when everyone is armed with production tools that make even the least-talented among us able to produce gorgeous creative works? What tools will become our go-to tools for production?

We’re headed toward a future in which theme parks may be centered around virtual reality experiences, in which our computer “screens” may be augmented reality visuals suspended in front of our faces, and in which anyone can create a full-fledged Pixar-like film in seconds. The plates are shifting under our feet, day by day. When we add up those small, consistent movements, they amount to a very different world just around the corner.

Sources & Additional Reading

Resetting the Score | Benedict Evans

Parsons and Roblox Collaborate on a Class | The Verge

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: