4-Wheel Suitcases and Innovations Hiding in Plain Sight

Category Creation vs. Category Reinvention

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 65,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

4-Wheel Suitcases and Innovations Hiding in Plain Sight

If we’ve had mass air travel for 80+ years, why did it take us 70+ years to make suitcases with four wheels?

Notion’s Ivan Zhou posited this question on Twitter over the weekend, and I found it an interesting thought exercise. From Ivan’s chronology:

1900s: Suitcases become common with steamers

1960s: Mass air travel takes off

1970s: First patents for wheeled luggage emerge

1990s: Male pilots start using wheels, breaking a feminine stigma of “wheels = weak”

2010s: The rise of China’s economy and tourism leads Chinese factories to commoditize spinner wheels

2010: LVMH buys Rimowa and turbocharges it, making upright luggage fashionable

Damn. It took a combination of product innovation (patents), mass adoption (air travel), social de-stigmization (changing gender attitudes), and globalization (China) to get us a no-brainer (at least in hindsight) product. My shoulders still hurt from lugging around an oversized duffel in the 2000s and 2010s.

Ivan then asks what suitcases can teach us about AI adoption. My view: we’re still in the “suitcases for trains” era, with mass adoption yet to come and “obvious” product innovations still far off. Consider this: 71% of the Fortune 500 still rely on mainframes. IBM, a stock I would short in a heartbeat, underpins most of that. Mainframes, in fact, handle 90% of all credit card transactions and manage 68% of the world’s production IT workloads. In the year 2024. Nearly three-quarters of companies still run on these:

AI, as we think of it today, is new. Only in the 2010s did GPUs become powerful and affordable enough to drive AI improvements in areas like language models and image recognition. If this is a 50-year tech cycle, we’re in the early innings. So what are the equivalents of four-wheel suitcases—the things that will deliver 10x better products (and “duh” moments) when they eventually arrive?

Some ideas that come to my mind:

AI personalization in e-commerce:

We will all get hyper-personalized shopping recommendations. And shopping will be conversational. Instead of sorting for “mens” and “jackets” and “black” on a website, we’ll say, “Find me winter coats under $300 that pair well with both dress shoes and sneakers, that I can wear to my work at a tech startup in Brooklyn but also on upstate trips.” We’ll go to Amazon for search-driven shopping (“paper towels”) and we’ll go to [fill-in-the-blank company] for conversational commerce.

AI product design:

We’ll be able to wear or use any product we can dream up. Mass production will turn into mass personalization. An example here is Arcade, the new company from Mariam Naficy. Arcade is starting with jewelry and rugs as its first two categories. If you think about it, why shouldn’t you get your own custom products, straight from your imagination? A combination of (1) creative tooling for AI product design, and (2) better supply chain / manufacturing will make this possible.

AI healthcare diagnostics:

As AI models ingest huge swaths of health information, we’ll get better diagnostics. And models trained on our own data—probably connected to our wearables or a phone app—will better personalize and optimize our own health. We’ll get a “virtual doctor” that will analyze any symptoms, health history, or genetic data to improve our our lifestyles and health outcomes.

AI language translation:

Two years ago in Crazy Ideas we posited the end of subtitles. From that piece:

We joke about bad dubbing in movies—and it’s almost always better to watch a foreign film with subtitles. But technology is rendering both dubbing and subtitles moot. We’ll live in a world where Trump can deliver a speech in Mandarin, where MrBeast can hold an online meet-and-greet in Tagalog, and where you won’t even know that your favorite YouTuber—whose videos you adore in English—only speaks Russian in real life.

This isn’t so far off. AI products will seamlessly translate any language in any context—even for idiomatic or cultural nuances—which seems simple in hindsight, but which will require immense computational and contextual advances to become broadly adopted.

When I think about big ideas, I tend to break them into (1) Category Creation and (2) Category Reinvention. Let’s take both in turn.

Category Creation

Many of the largest venture outcomes were category-creating companies. Uber is the canonical example, pioneering the ride-hailing market. Uber wasn’t really disrupting taxis; it was creating its own new market.

As Bill Gurley outlines in a post from 2014, many experts dramatically underestimated Uber’s market opportunity. One finance professor at NYU, Aswath Damodaran, wrote in Uber’s early days: “For my base case valuation, I’m going to assume that the primary market Uber is targeting is the global taxi and car-service market.” He arrived at a TAM of $100 billion.

Damodaran’s error, of course, was not recognizing that Uber’s product would expand the market. As Gurley points out, Uber offered a 10x better offering than taxis.

✅ Coverage density was higher, which drove down average wait times to under five minutes

✅ Geolocation on mobile devices enabled anyone to call a car, nearly from anywhere

✅ Payment was done via mobile, meaning customers didn’t need to carry cash

✅ The dual rating system ensured quality

✅ Digital record of each ride meant that Ubers were safer than cabs

This set the stage for category creation, and Uber has ridden that creation to a $160B market cap.

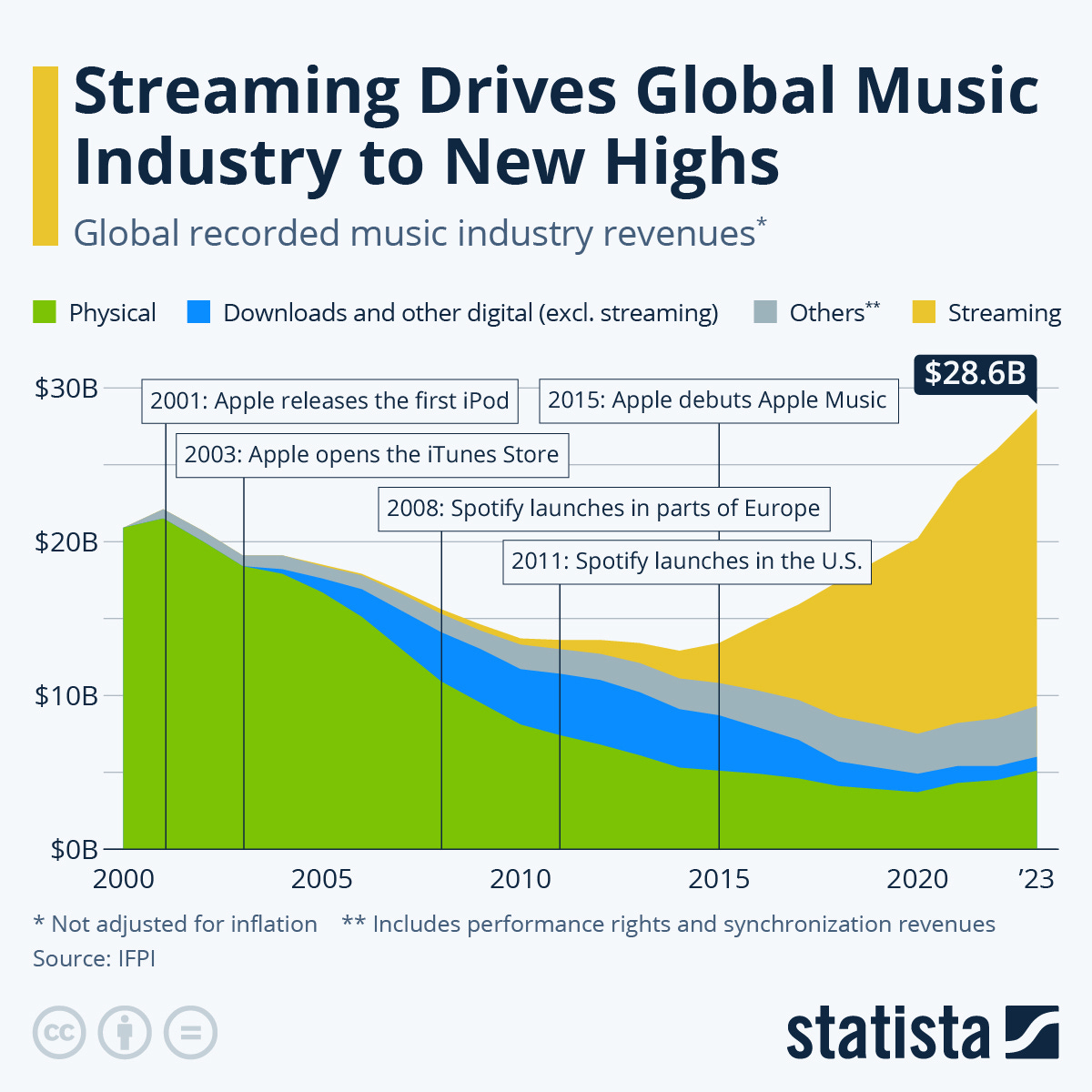

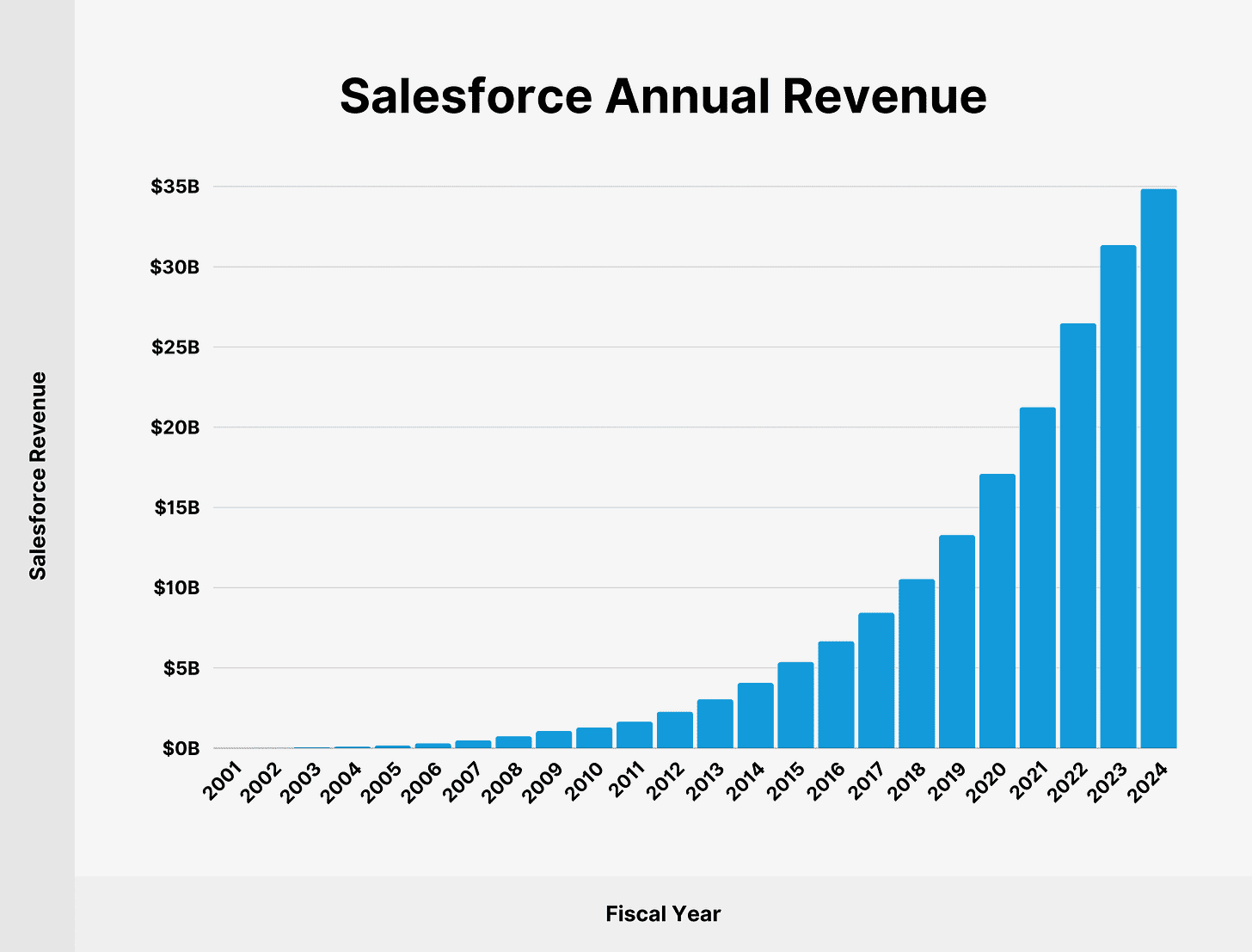

Other stories of category creation tell a similar story. Think Spotify in music streaming; the company has a market-leading 32% market share, ahead of two of the most well-funded and formidable competitors on the planet (Apple and Amazon are #2 and #3). Or in B2B, think Salesforce: Salesforce pioneered software-as-a-service as a business model and cloud-based CRMs as a product.

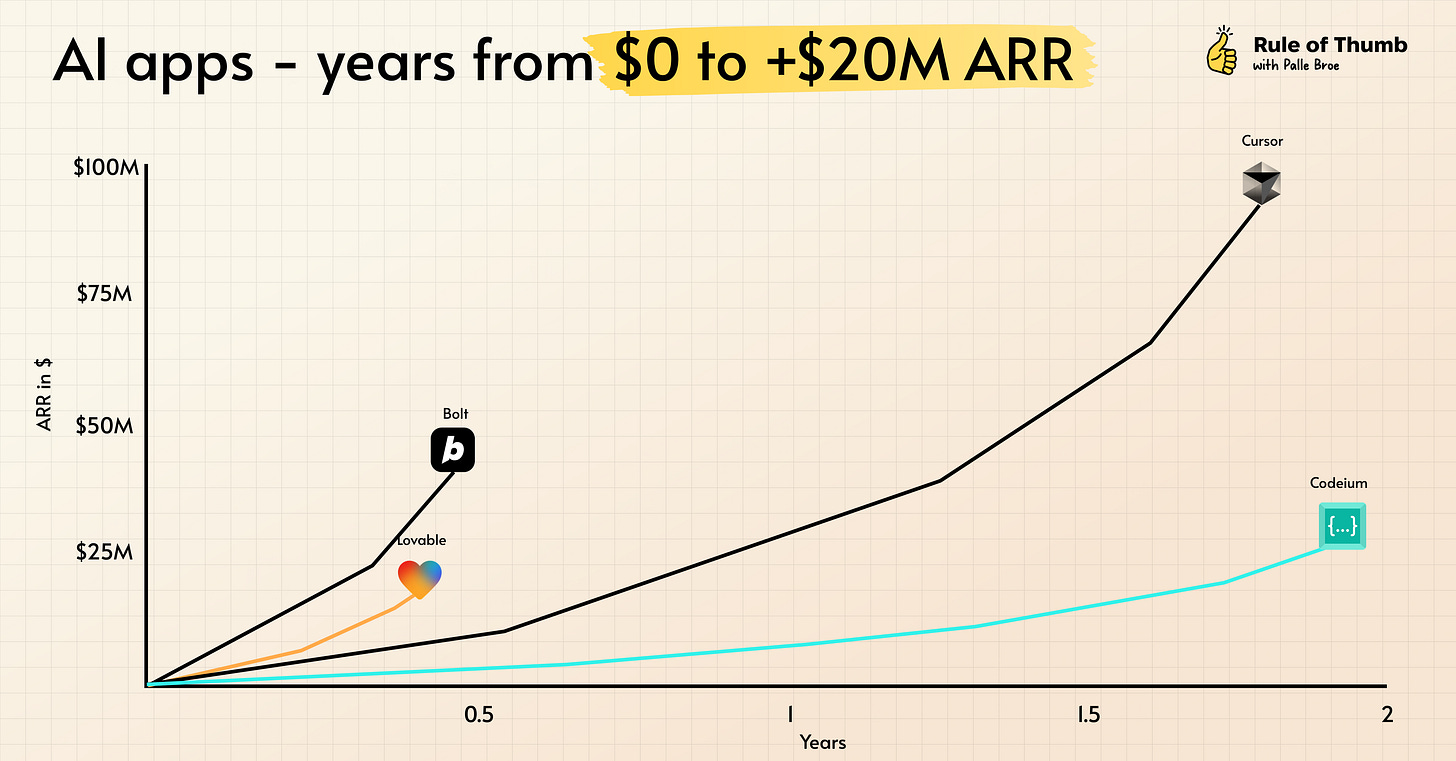

When I think about category creation today, I think about some of the examples earlier—AI conversational commerce, AI doctors, AI language translation. Earlier this year we wrote The Age of Fragmentation: AI’s Impact on Content and Code. That piece honed in on two examples—Sekai in AI content creation, and Lovable in AI code creation. Sekai is an example of category creation: Sekai—whose name means “world” or “earth” in Japanese—is a gen AI storytelling platform built on the blockchain. You can think of Sekai as fan fiction on steroids, with new tools for content production and new rails for content ownership. This is category creation, in the same way that YouTube pioneered online video (with Flash as the enabling technology).

The second example from that piece, Lovable, is an example of category reinvention.

Category Reinvention

A common form of AI innovation right now isn’t creating a new category, but rather AI-ifying an existing category. Take website builders—Squarespace is an example of an incumbent, but Squarespace is vulnerable to the Lovables of the world, which can spin up a website in seconds (and, yes, do a lot more).

Below is the output for when I write the prompt:

Can you create a landing page for my venture capital firm, Daybreak, that shows a pretty sunrise and explains that we are a thesis-driven venture capital firm focused on partnering with early-stage technology companies?

This isn’t to pick on Squarespace. Wix and Webflow are just as vulnerable. And Lovable isn’t the only disruptor: Bolt is a US competitor that is reportedly even faster-growing, 0 to ~$40M in about four months:

The first wave(s) of software companies digitized the world. Now past winners are being disrupted by new AI-native challengers.

I like how Michael Dempsey puts it:

If the prior decade of technology as an asset class was about incumbent industries being swallowed up by tech, leading to an expansion of the market cap of “tech” as a category, then the next may be about disruption and market cap destruction within tech itself.

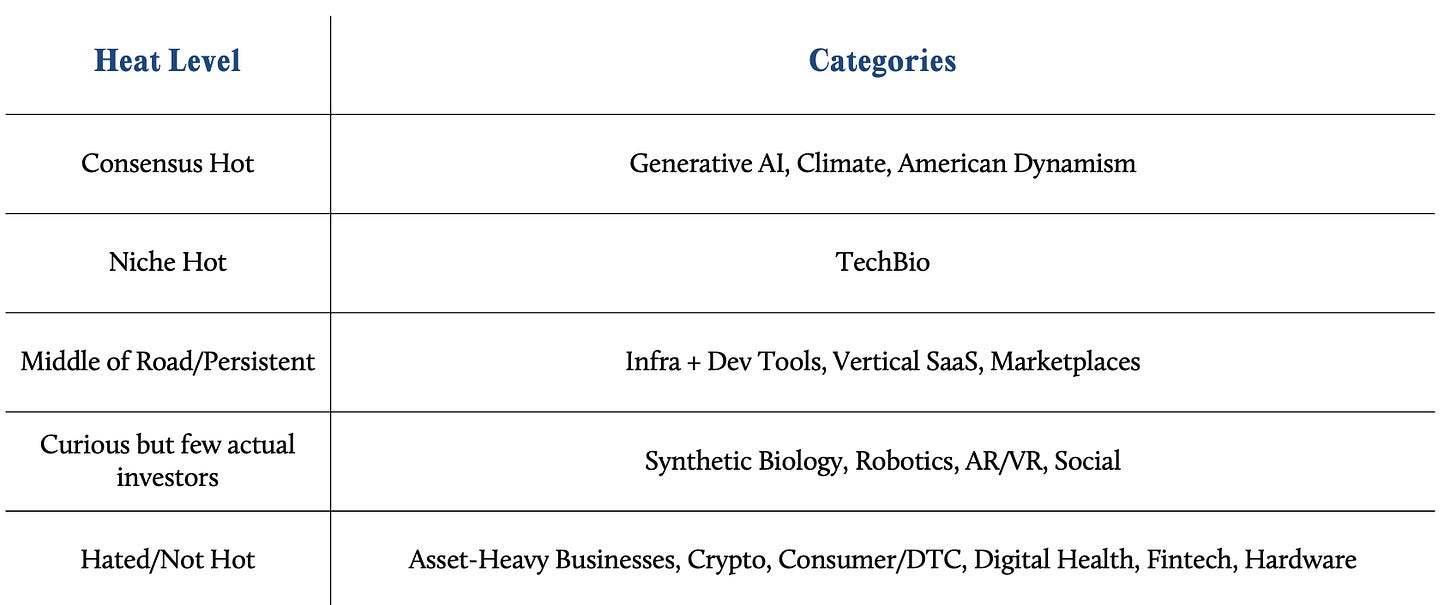

Michael includes this nice graphic, which effectively captures what’s “hot” and what’s “not” in venture circles.

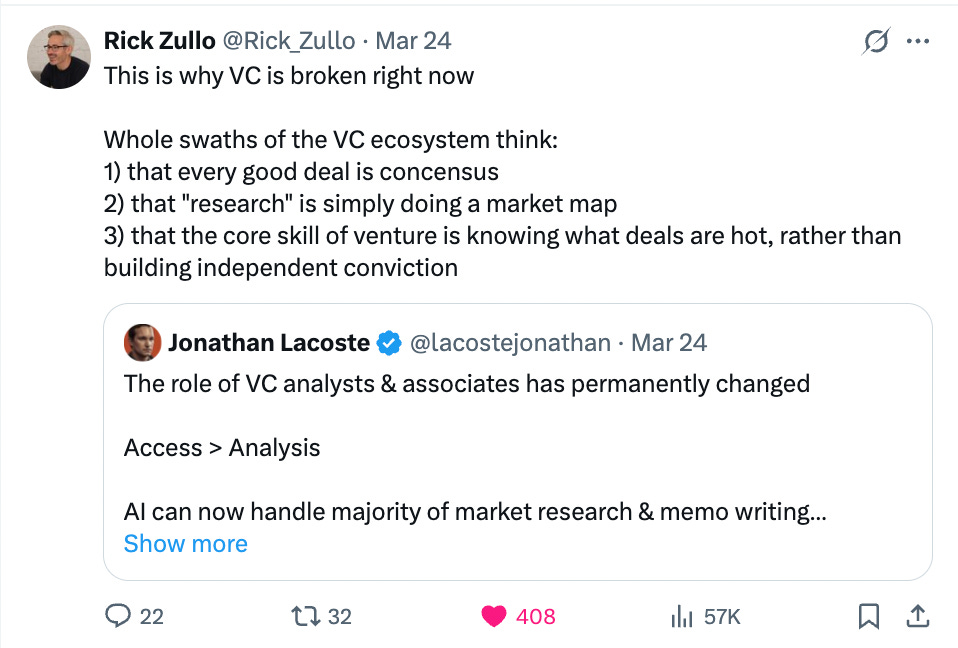

A tweet made the rounds this week bemoaning how junior VCs have become incentivized to chase hot deals, rather than practicing original thinking. This is spot on; don’t even get me started on the incentives at venture firms. A good forcing function for building independent conviction: think through what categories don’t exist today, but could exist (and be huge) in five years—or think through which categories are uniquely vulnerable to reinvention.

Final Thoughts

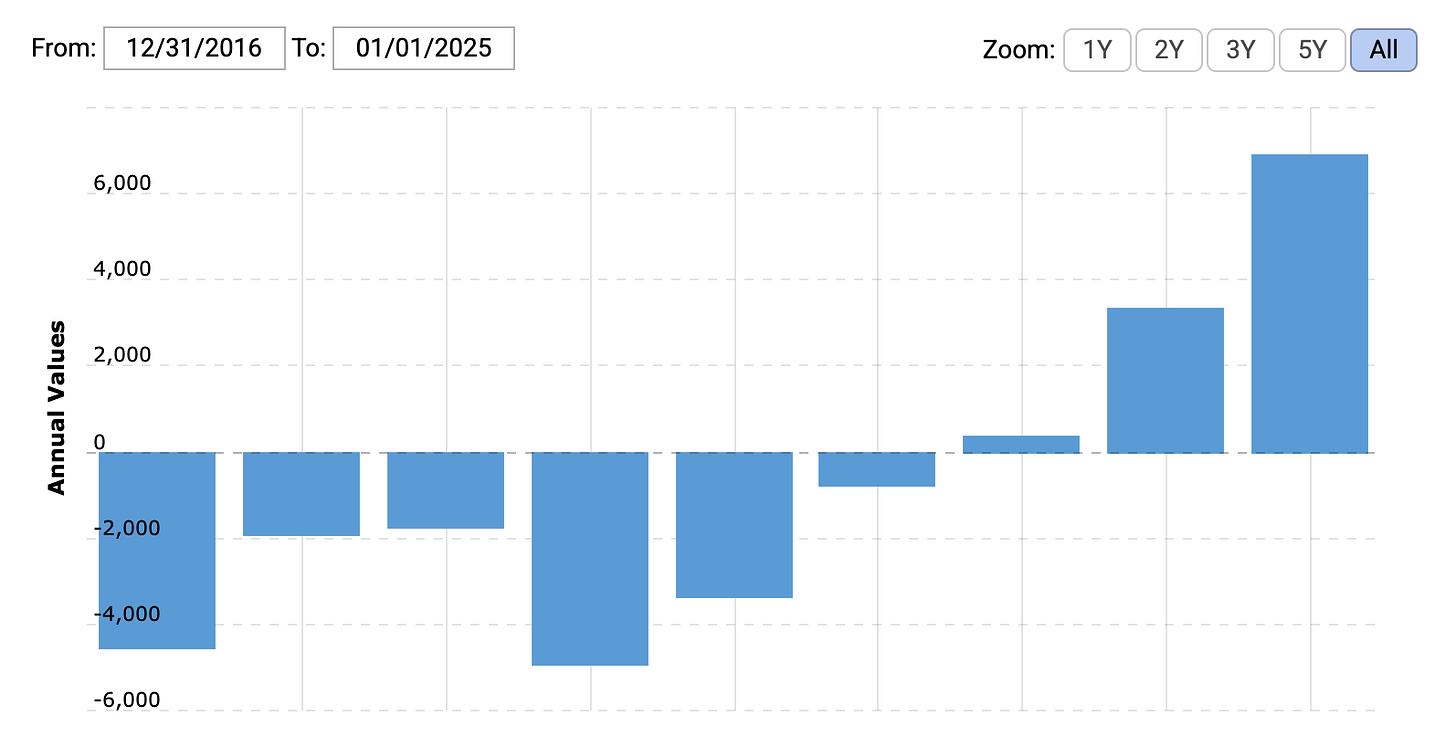

When it comes to new categories, not everything needs to work right away. To return to the Uber example: Uber burned tremendous sums of money for years to create its category and cement its category-leadership. Now, Uber is finally reaping the rewards: free cash flow for 2024 was nearly $7B, over 2x 2023 free cash flow (which itself was nearly 8x 2022). The J-curve is working.

In AI, many companies will have a hell of a J-curve. With how fast the industry is changing—and how quickly costs are dropping—things will probably work out for category leaders. Cursor may be giving ~70 cents of every dollar it makes to Anthropic right now—but long term, that probably won’t be the case. OpenAI is also following a ferocious J-curve.

When it comes to category reinvention, it’s all about timing. Thing about Figma displacing Sketch and Invision by building on WebGL. Think about Robinhood disrupting E*Trade by being mobile-first. To take a more recent example:

This week, 23andMe filed for bankruptcy. In its wake, a new company will probably emerge. One contender is Nucleus Genomics. I liked how its founder, Kian, framed the timing difference between 23andMe’s founding and now:

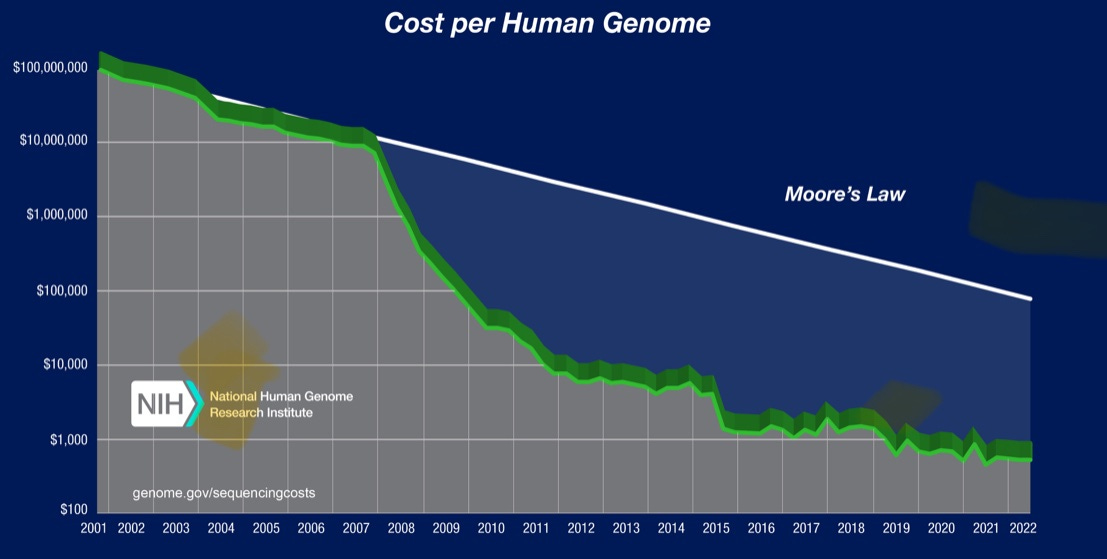

The number one greatest detail that is currently being missed from this story is the chart below. When 23andMe launched in 2006, it cost about $10 MILLION to read all of someone’s DNA (“whole genome” test). Hence, the technology 23 used missed millions of genetic markers that could dramatically shape someone’s health, and future family.

Now? This whole-genome test cost just a few hundred dollars. We can now finally bring — to everyone — a true DNA health test: family planning, disease risks, how your DNA affects your metabolism of different drugs — and more — into a single cheek swab.

Here’s the visualization:

23andMe impressively built a household name around DNA testing. But its timing was probably off (and the company made a number of other mistakes too). When it comes to category reinventions, timing trumps everything. We’ll going to see a number of categories re-made, from website development to DNA testing.

Sources & Additional Reading

Here is Ivan’s tweet

I liked Michael Dempsey’s writing on category creation

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: