5 Lessons from China's Internet Companies

This is a weekly newsletter about how people and technology intersect. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

5 Lessons from China's Internet Companies

A decade ago, China leapfrogged the West on consumer internet innovation. The changing of the guard coincided with the rise of mobile. Many people in the U.S. and Europe were first introduced to the internet on desktop—on their Macintosh, their Dell, their Macbook. And the West remains stubbornly desktop-centric: many consumers still wait to make a big purchase until they’re back sitting at their computers.

China, meanwhile, is mobile-first. Most Chinese were introduced to the internet through mobile devices. Back in 2014, mobile internet users in China surpassed desktop internet users, and the gulf has only widened: today, 1.4 billion Chinese access the internet via mobile devices, 3x the number who visit the web through desktop. The proliferation of cheap smartphones (Xiaomi, for instance, sells its devices just above cost, instead making its profit from its online services business) brought the mobile internet to China’s Tier 3 and Tier 4 cities.

The mobile era made China one of the most interesting places to look for consumer internet innovation; Chinese tech startups were often harbingers of new products and consumer behaviors in the West. And as the world continues to cleave into two internets—driven by U.S.-China geopolitical conflict—it becomes less likely that China’s tech companies will directly bring these innovations to the U.S. and Europe. (TikTok is the only Chinese app to ever gain real traction in the West.) Instead, new startups in the West will learn from and then replicate many of China’s innovations.

Earlier this summer, I wrote about Soul, a Chinese social app with 33 million monthly active users. Soul—which describes itself as “an algorithm-driven online social playground”—had a line in its IPO filing that caught my eye:

“We have especially attracted young generations in China, who are native to mobile internet and who therefore more palpably experience the loneliness technologies bring.”

That line captures the double-edged sword of consumer technology. As more of our lives go digital, we more deeply feel the gaps where rich, in-person interactions used to be; the best of technology will never be able to replace the best of human interaction. This is most acute for digital natives: 79% of Gen Zs report feeling lonely, compared to 71% of Millennials and 50% of Boomers. And yet, technology is also a salve for that isolation, connecting us in new ways to new people. Technology is both a source of modern loneliness and an antidote.

China—whose young people are even more mobile-native than America’s—has innovated on technology solutions to loneliness. Soul mentions the word “community” 43 times in its F-1 filing. There are many interesting learnings from China’s internet companies; this week, I’ll go through five learnings built around the common theme of community.

Bullet Commentary & the Hive Mentality

Social Serendipity

Participatory Experiences

Collaborative Learning

Social Commerce & Livestreaming

Bullet Commentary & the Hive Mentality

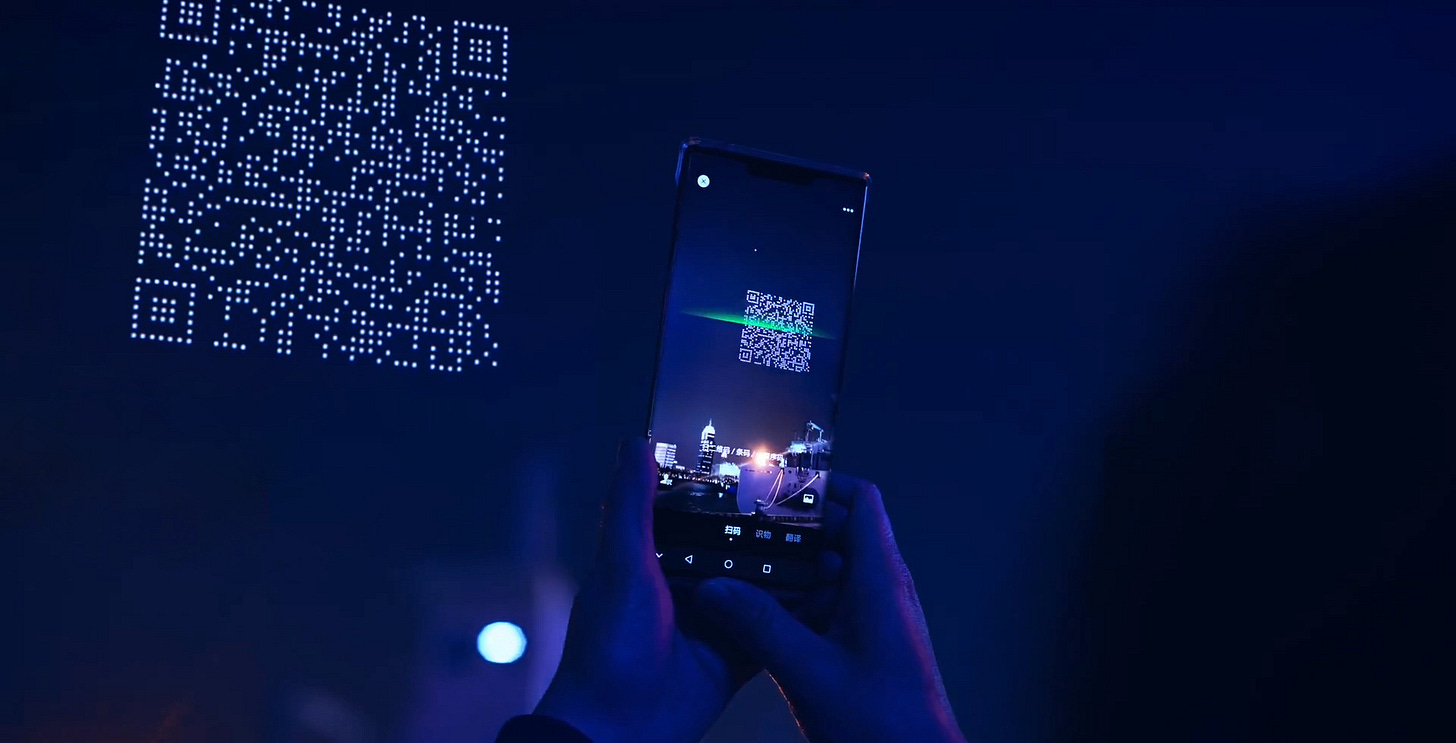

Bilibili is one of the most fascinating companies in China. What other company acquires new users by having 1,500 drones form a giant QR code in the Shanghai sky?

Scanning that QR code, by the way, downloads one of Bilibili’s most-popular mobile games.

Bilibili is a community-centric social app with a $35 billion market cap—202 million monthly active users spend 75 minutes a day on the app. Bilibili is built around shared interests and purposefully builds friction into community. In order to join a community, users have to pass a 100-question exam. A representative question to join the Harry Potter community, for instance, is: “How many horcruxes does Voldemort have?” (Any self-respecting person should know the answer is seven.)

Building friction into community ensures best-in-class retention: ~85% of Bilibili users retain after 12 months.

Bilibili originated as a place for anime enthusiasts, but has since expanded to music, dance, science, film, fashion, and more. There are communities for virtually everything. In the West, we’ll see more companies build friction into their communities to boost engagement and retention.

The most interesting feature of Bilibili—and the one most central to community—is bullet commentary. When you consume content on Bilibili, comments from fellow community members flash across your screen, time-stamped to when that user had that reaction. Only members of the community—those who passed that 100-question exam—can leave comments, ensuring quality.

Anyone who has read YouTube comments will be familiar with comments like “2:43 had me in tears” or “0:43 my jaw dropped”. Bullet commentary takes that concept and integrates it directly into the content in real-time. I like how Lillian Li describes the feature: “The feeling from watching a video with bullet commentary, after the initial chaos, is one of tapping into the hive mind, or sitting in a rambunctious movie theatre, or following a show’s live tweets.” For a deeper-dive on how bullet commentary works, DJY Research has a great piece here.

One reason that TikTok succeeded is that the internet has eroded our attention spans; 15-second videos hold our attention better than YouTube videos or a Netflix show. Bullet commentary builds on the same premise. Most Gen Zs scroll their phone while they watch TV—the show alone isn’t enough. When you watch a Presidential Debate or NBA final, how often are you checking live reactions on Twitter or internet message boards? Bullet commentary embeds that community directly into the product, letting you tap into the hive mind and find camaraderie through your screen.

Social Serendipity

In Bowling Alone, a seminal work on American loneliness published in 2000, Robert Putnam wrote:

“Serendipitous connections become less likely as increased communication narrows our tastes and interests. Knowing and caring more and more about less and less. This tendency may increase productivity in a narrow sense while decreasing social cohesion.”

Putnam’s words—written four years before Facebook was founded—foreshadowed the algorithmic echo chambers that would define the social web. Our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter feeds sorted us into secluded corners of confirmation bias.

AI may be the solution to serendipity. AI-driven feeds untether the social graph from our offline connections: instead of hanging out online with the people you went to college with, you can forge new friendships and uncover new content creators. Bytedance’s suite of AI products—including TikTok outside of China—are the most successful AI-powered social products to date. Where Facebook is for utility, TikTok is for discovery.

TikTok’s algorithms surface content based on how good it is—factors feeding the algorithms range from how many people interact with a video (like, share, comment), to a video’s completion rate, to your location. Last year, TikTok shared how its algorithms work in an effort to be more transparent during U.S. government scrutiny.

TikTok’s China counterpart, Douyin, has a formidable competitor that’s lesser-known outside China. Kuaishou just reached 1 billion monthly active users (about on par with Instagram) who average 85 minutes a day on the app. Within China, Douyin and Kuaishou popularized algorithmic video feeds and serendipitous content consumption. Soul extended the concept to a social graph, pairing anonymous users based on shared interests.

U.S. startups are following suit. Clubhouse recommends audio rooms, often full of complete strangers. ItsMe, through its avatar interface, matches you with new people around the world. And Honk lets you discover people to chat with based on your interests.

AI also has a dark side: our TikTok feeds can rapidly become echo chambers, showing us what we want to see and exposing us to only like-minded people. Tech is a double-edged sword and guardrails need to be in place. But who we find community with is no longer limited to who lives on our street or who goes to our school. That’s progress. Our online social graphs are no longer dependent on our offline connections.

Participatory Experiences

In China, there’s a fascinating dating app called Yidui. Yidui users go on a video date chaperoned by a matchmaker, who helps guide the conversation and keep the date on track. At the same time, viewers—often thousands of them—can livestream the date. Viewers type in the chat and suggest conversation topics, give reactions to how they think the date is going, or send virtual gifts to the people on the date.

“Yidui matchmaker” is a new job title: 40,000 professional matchmakers arrange ~10 million dates every month for ~50 million users.

Yidui, like many Chinese internet companies, doesn’t fit cleanly into one bucket. Is it a dating app? A livestreaming app? An entertainment platform? A chat app? It’s all of the above, and more. It’s a place for communities to congregate around the shared experience of finding a mate.

Most fascinatingly, Yidui takes one of the most private (and, often, most awkward) life experiences—going on a first date—and turns it into a widespread community activity. To some, this is horrifying or blasphemous; to others, the companionship is welcome. Yidui shows that on the internet, everything—even the most intimate life experiences—can be participatory and social.

Collaborative Learning

Last fall, in a deep dive into the education sector, I shared this chart to emphasize that tutoring companies dominate edtech.

The rankings have shifted since then—Byju’s now holds the top slot after its most recent raise, and Coursera went public and sits at a ~$5 billion market cap. But the takeaway remains the same: tutoring marketplaces are often the largest and most scalable education companies, with strong network effects—every additional tutor and learner leads to a better experience for everyone.

Chinese tutoring companies are among the largest, as 43% of urban Chinese household income goes toward supplemental education. In the U.S., it’s closer to 2%.

Last week, the Chinese government cracked down on the tutoring market, citing its burden on families. (The cost of supplemental education has been tied to lower birth rates, as parents often can’t afford to educate more than one child.) Overnight, the multibillion-dollar Chinese private education market all but evaporated.

Despite China’s crackdown—another proofpoint of how challenging it’s become to do business in the country—the West can learn from Chinese tutoring marketplaces. Edtech in the U.S. and Europe remains solitary—some form of Zoom school and individual assignments. It’s telling that America’s most valuable education startups are MOOCs (massive open online courses), which have suffered ~5% completion rates because they uncouple community from learning.

Post-COVID, the share of U.S. household spending toward supplemental education will be meaningfully higher—not at China’s levels, but likely in the mid-single-digits. And the next generation of edtech companies will build community into the product. This is happening both in tutoring marketplaces that provide peer-to-peer learning, as well as with cohort-based courses offered by companies like Maven, Reforge, and Section4. As in China, Western technology-based learning will be more collaborative and social, solving many of the problems that plagued the first generation of edtech.

Social Commerce & Livestreaming

The melding of social and commerce is more advanced in China than in the West. Two companies come to mind.

Xiaohongshu—which means “Little Red Book”—is like Instagram if Instagram had introduced Instagram Shop years earlier and made it its premier feature. Xiaohongshu has always been more commerce-centric than Instagram, focused on discovery-driven and serendipitous shopping—the digital equivalent of browsing the mall. It’s the counterpart to more search-driven shopping sites like Alibaba’s TMall or JD.com.

Pinduoduo—which translates to “together, more savings, more fun”—is even more social in how it approaches commerce. The company encourages you to shop with friends by giving you discounts on group orders. Social connection is built into the shopping experience. Pinduoduo, or PDD, has had a remarkable run—since its IPO in 2018, its market cap has swelled from ~$20 billion to ~$110 billion. In 2020, PDD reported 788 million active buyers—more than the 779 million on Alibaba, a company 16 years older.

For years, people have touted the rise of social commerce in the West but we haven’t seen any players break through. My (non-expert) thesis is that there’s a distinction between the U.S. and China in how platforms evolve: in China, it’s possible to combine social and commerce from the start; in the U.S., though, you have to start with social and layer in commerce over time. This may be because of how natural mobile shopping is to Chinese internet users, or it may be because of the dominance of U.S. social platforms. But the winners in social commerce (so far) are the big social apps.

The exception to this may be in vertical opportunities within social commerce. Within food, for instance, Snackpass describes itself as “food meets friends” and lets you gift your friends food. It’s creative and unlike anything else out there.

There are also interesting intersections between social commerce and livestreaming, another innovation from China. In 2020, livestreaming in China was a $60 billion market reaching 617 million people—62% of all Chinese internet users. Those people tune in to popular creators like Austin Li Jiaqi, known as “The Lipstick King” for trying on 380 lipsticks during a seven-hour livestream. Livestreaming and social commerce go hand-in-hand: Li Jiaqi sold 15,000 lipsticks to his viewers in just five minutes, grossing $145 million on Taobao during China’s Singles’ Day.

Livestream commerce is nascent in the U.S., but it’s beginning to take hold. As in non-livestream social commerce, vertical platforms have the most traction. Whatnot, a livestream shopping site for collectibles, is the largest today.

In the coming years, both social commerce and livestreaming (as well as the growing intersection of the two) will continue to take hold in the West, following China’s example.

Bonus: Business Model Shifts

One through-line that cuts through all of the above is business model innovation. U.S. consumer internet has long been reliant on digital advertising. Partly because it matured on mobile—at a time when mobile advertising was less proven and mature—the Chinese consumer internet pioneered more creative and diversified revenue streams. Take Facebook and Tencent. Facebook earns 99% of its revenue from ads; Tencent stitches together ads, payments, mobile gaming, and value-added services.

Digital advertising isn’t going anywhere; massive businesses have been build on its back. Google revenue grew faster last quarter than it has in a decade.

And many large Chinese companies still rely on advertising. Pinduoduo, despite being an e-commerce company, makes almost all its money from ads rather than from its 0.6% cut of gross merchandise volume. Bytedance is already the third-largest advertising company in the world after Google and Facebook (and ahead of Alibaba and Amazon).

Crucially, sometimes advertising is the right model. YouTube and Netflix will both do about $30 billion in revenue this year with dramatically different business models and cultural impact. YouTube has 2.5 billion users to Netflix’s 200 million.

But the West will continue to shift to more diversified and less ad-centric models. This is largely because Google, Facebook, and Amazon together command almost $0.75 of every $1 spent on digital advertising. Advertising is also a ~$700 billion market that’s already ~50% online; commerce is a ~$20 trillion market that’s ~20% online.

Tencent, Bilibili, and Kuaishou all rely heavily on “value-added services”—things like micropayments and subscriptions and virtual currencies. More Western companies will turn to VAS, particularly if Apple and Google reduce the 30% tax they take on every digital economy. Already, Discord and Clubhouse have eschewed ads and Facebook, Snap, and Amazon all have virtual currencies within their ecosystems. Business model innovations—many borrowed from China—will define the next decade of the consumer internet.

Final Thoughts

From 1965 to 2008, the frequency of the word “I” in American books doubled. A study of magazines found that themes of family dominated in the 50s—“Love means self-sacrifice and compromise”—only to be replaced by themes of independence in the 60s —“Love means self-expression and individuality”. In Bowling Alone, Putnam writes: “People divorced from community, occupation, and association are first and foremost among the supporters of extremism.” Some part of today’s partisanship and populism no doubt stems from rising loneliness and the urge for belonging.

Over the past 50 years, America has continued its steady march from collectivism to independence, and technology has contributed to that shift. But technology is also an answer for loneliness. Chinese companies have recognized that tech is both the root of the problem and the potential solution to it. They’ve innovated in consumer social, in education, in commerce. Many of the fastest-growing Chinese startups are built on the premise of bringing people together.

On a recent episode the Sinica podcast, Lillian Li quoted the economist Douglass North on the definition of institutions: “Institutions are the rules of the game in a society, or, more formally, are the humanly-devised constraints that shape human interaction.” She then made an astute observation: the big tech platforms are the new institutions. Over the last half-century in America, institutions have rapidly lost power. Churches, for instance—once the connective tissue of many communities—saw membership dip below 50% for the first time in 2020.

As institutions wither, tech platforms accrue power. They are the new institutions—the humanly-devised constraints shaping human interaction. Hopefully, the next generation of internet companies will build in social features that bring people together, creating community online that’s sorely lacking in the analog world.

Sources & Additional Reading

Two great reads on Bilibili are this piece from Lillian Li and this piece from DJY

For a deep-dive on bullet commentary in particular, read this piece from DJY

To learn more about Pinduoduo, Acquired has a great podcast episode

Related Digital Native pieces: