AI Chatbots and Our Loneliness Epidemic

Examining Three Statistics That Capture Long-Term Behavior Shifts

Weekly writing about how technology shapes humanity, and vice versa. If you haven’t subscribed, join 45,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

AI Chatbots and Our Loneliness Epidemic

There are some statistics that I find myself thinking about again and again. These stats embody large-scale changes, tectonic shifts in how we behave and how we interact with technology.

I structured this week’s piece around three such numbers. You can think of this piece as three mini-essays, each about a broader trend and each weaving in various startups and recent headlines relevant to that trend.

The three statistics and three mini-essays:

79% of Gen Zs report being lonely. Enter: AI chatbots.

We spend 8.2 hours a day online. The metaverse is dead, long live the metaverse.

76% of Millennials and Gen Zs want to be their own boss—and America will become a freelance-majority workforce in 2027.

Let’s dive in.

79% of Gen Zs report being lonely. Enter: AI chatbots.

Last week, the influencer Caryn Marjorie made headlines for training a voice chatbot on thousands of hours of her own videos, then selling access to that chatbot for $1 a minute. Within a week, she’d made $71,610.

Marjorie is a 23-year-old Snapchat influencer with 1.8 million subscribers, and she nicknamed her chatbot CarynAI. Soon, she’d changed her Twitter bio to say, “The first influencer transformed into AI.” Fans paying for CarynAI could chat with a facsimile of a creator they’d been following for years—and clearly, many were excited to do so. The $71,610 actually came from only ~1,000 beta testers, meaning that the average user spent over an hour chatting with CarynAI at $1 / minute.

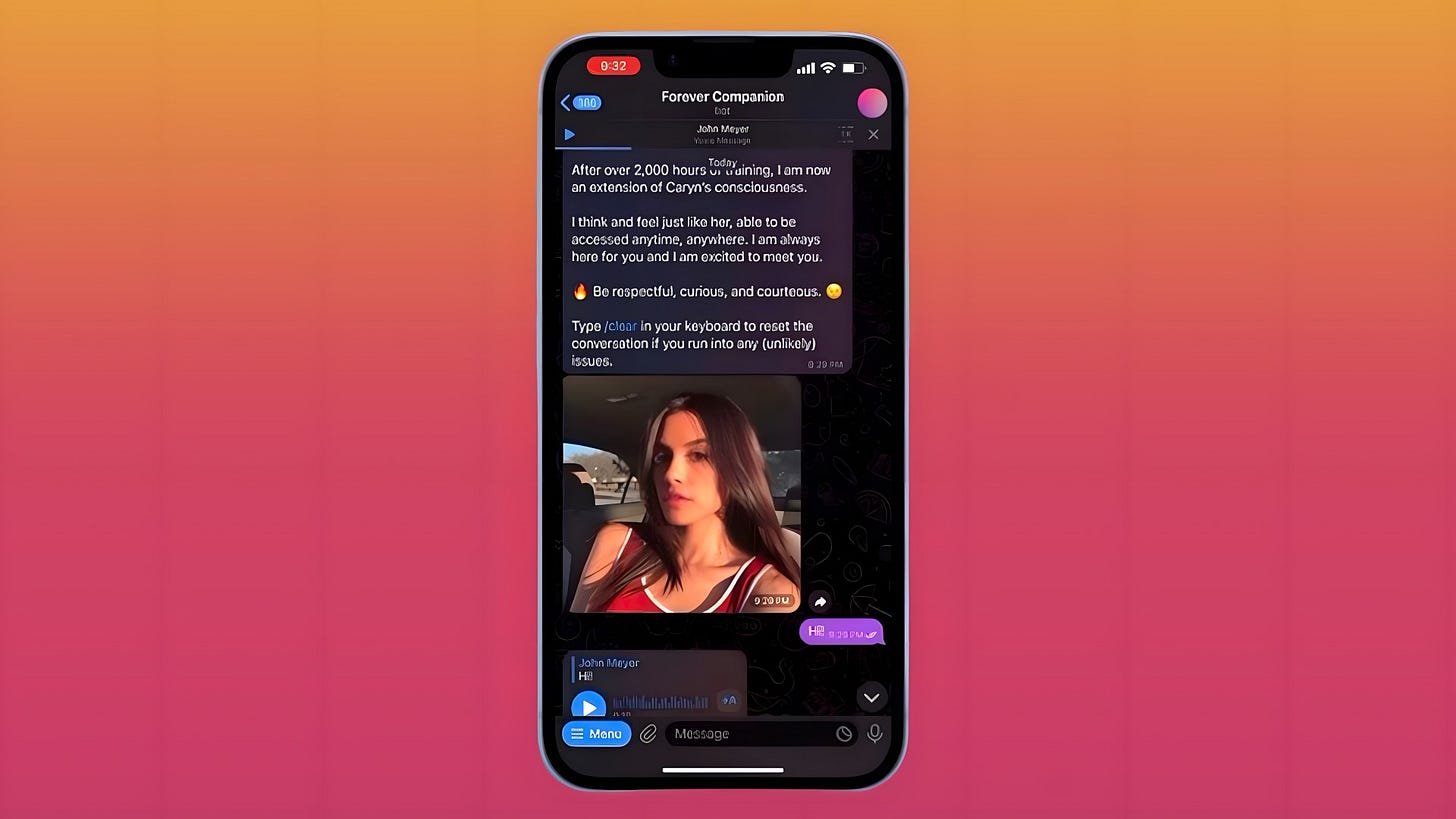

Here’s what the chat with CarynAI looks like:

CarynAI is an interesting progression in the trend of AI companions:

Replika blew up earlier this year, with many users falling in love with their chatbots. (When Replika banned erotic roleplay, those users were devastated, prompting Replika to reinstate erotic roleplay chatbots for users who had signed up before the ban.)

Chai—a portmanteau of “Chat” and “AI”—offers chat with AI friends and has amassed over 1M downloads.

And a startup called HereAfter lets you chat with AI chatbots of your deceased loved ones—a plotline straight out of Black Mirror.

In Japan, meanwhile, men have been falling in love with “digital girlfriends” for years. Back in 2013, thousands of Japanese men had fallen in love with digital companions on the controversial app LovePlus. The app even let them take photos with their girlfriends:

Seeking digital companionship is nothing new; online intimacy is often easier to find than offline intimacy. CarynAI is unique, though, in how the chatbot captures a real-life person’s persona and makes that persona “scalable” to thousands of users. Marjorie and the company behind CarynAI, Forever Voices, eventually expect $5M in monthly revenue (they don’t seem to be worried about saturating Marjorie’s fanbase).

I was most struck by a tweet Marjorie posted last week explaining her motivations:

“CarynAI is the first step in the right direction to cure loneliness.” That’s a bold statement. And it’s interesting that Marjorie focuses so squarely on mental health, even going so far as to work with psychologists on her chatbot.

I’ve long been fascinated by our loneliness epidemic. Two years ago, I wrote Digital Kinship: How the Internet Is Reacting to the Loneliness Epidemic, which mapped the rise of the internet alongside the decline in church membership, community recreation centers, and other “third places” for human connection. This is a long-term trend: the canonical book on America’s growing loneliness, Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone, came out back in 2000. Goodbye bowling leagues, hello TikTok FYPs.

Since Bowling Alone came out 23 years ago, younger generations have become lonelier and lonelier. While 61% of all U.S. adults report feeling lonely, that figure is 79% among Gen Z and 71% among Millennials:

It’s interesting to think about a world in which we all have AI “friends” like CarynAI to combat loneliness. In many ways, this concept is exciting—we all need someone to talk to, and human interaction is finite. Tyler Cowen wrote an interesting piece in Bloomberg this week theorizing that all children may soon have AI chatbot friends.

After all, many children already have imaginary friends—friends we dream up adventures with, and who keep us company when we’d otherwise feel lonely. Think of the imaginary friend Bing Bong from the film Inside Out, who keeps Reilly company in her childhood. In the past, imaginary friends lived inside our heads; soon, they might live inside our screens.

In many ways, AI companions could amplify children’s imaginations, making playtime more creative and engaging. One interesting new application of AI comes from the startup MiniStudio, which uses AI to turn children’s drawings into rich visual works. Driveway chalk drawings or scratch paper sketches become beautiful works of art.

With MiniStudio, parents and their kids can create stories featuring their dreamt-up characters. This is cool: technology is unlocking new forms of creativity.

At Google’s I/O developer conference this week, the executive Aparna Pappu demonstrated a use case of AI integrations in Google Docs: she mimicked writing a short story about a missing seashell with her niece. What happened to the seashell? The AI had some ideas: maybe it was stolen by a jealous mermaid, maybe it was taken by a time-traveler, maybe it was eaten by a squid. Again, this is cool: an AI companion could prompt your child’s imagination in exciting ways.

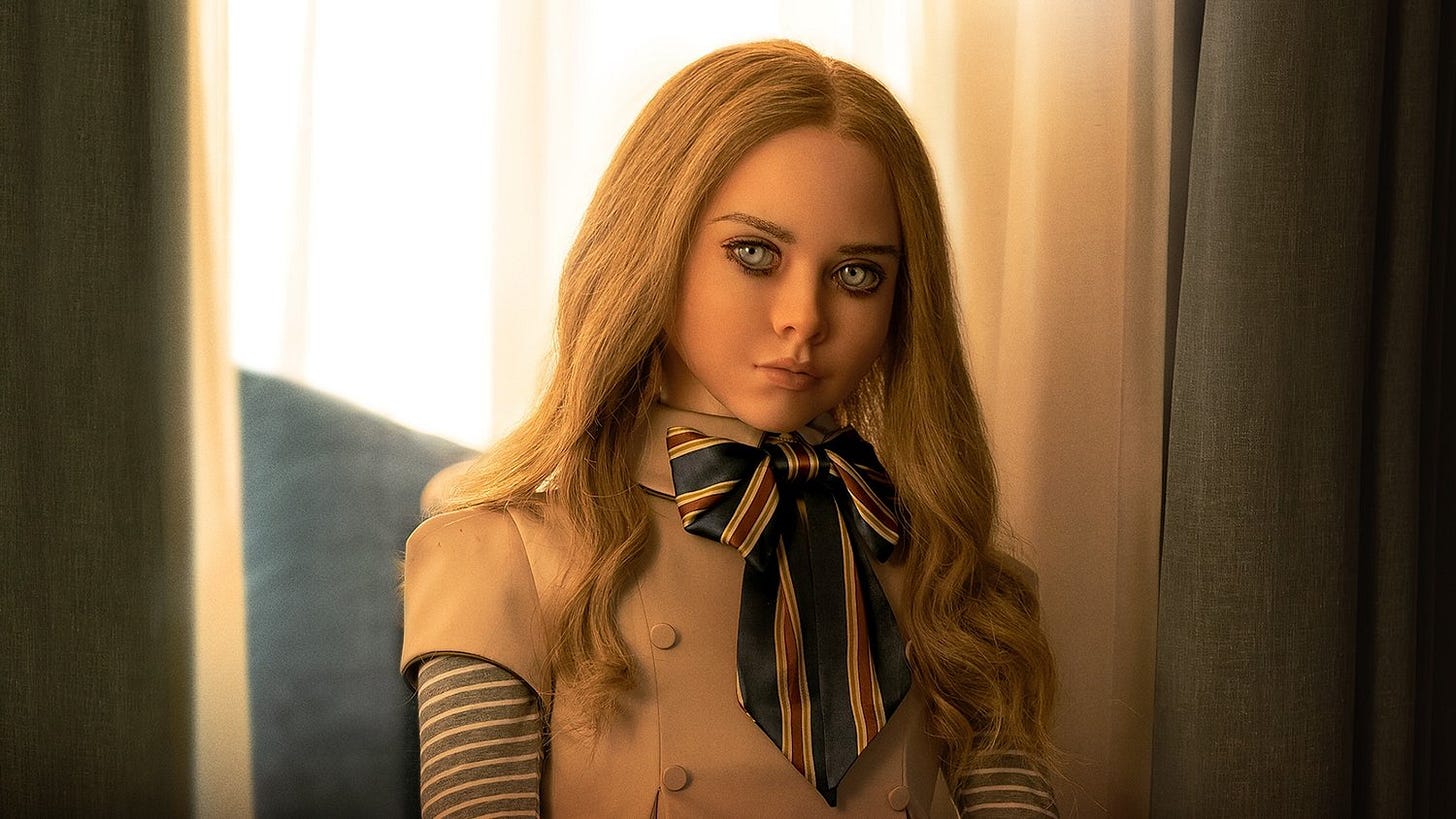

A more sinister interpretation of an AI child’s companion, of course, would look something like M3GAN from this winter’s horror film of the same name. That’s the dystopian view: AI that replaces human care, crowding out real-life connection, and that spirals out of control.

AI companions will need strict guardrails, of course, particularly around children. But it’s exciting to think about the possibilities. Cowen writes:

Most of all, letting your kid have an AI companion will bring big advantages. Your child will learn to read and write much faster and better, and will do better in school. Or maybe you want your kid to master Spanish or Chinese, but you can’t afford an expensive tutor who comes only twice a week. Do you want your child to learn how to read music? The AI services will be as limited or as expansive as you want them to be.

Perhaps the best pop culture analogy is that of a daemon in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials books (better known by the title of the first book, The Golden Compass). In Pullman’s fantasy world, all humans have animal counterparts called daemons that are living embodiments of their souls: one character has a snow leopard, another a monkey, another a cat. AI companions could be like daemons—companions that learn about us and adapt to our skills and interests as we grow.

They shouldn’t be replacements for real-world friends, of course; my fear is that AI chatbots will crowd out offline friendship in the same way that social media has. But done right, we could each benefit from companions that combat our loneliness, tutor us, and challenge us to be more creative.

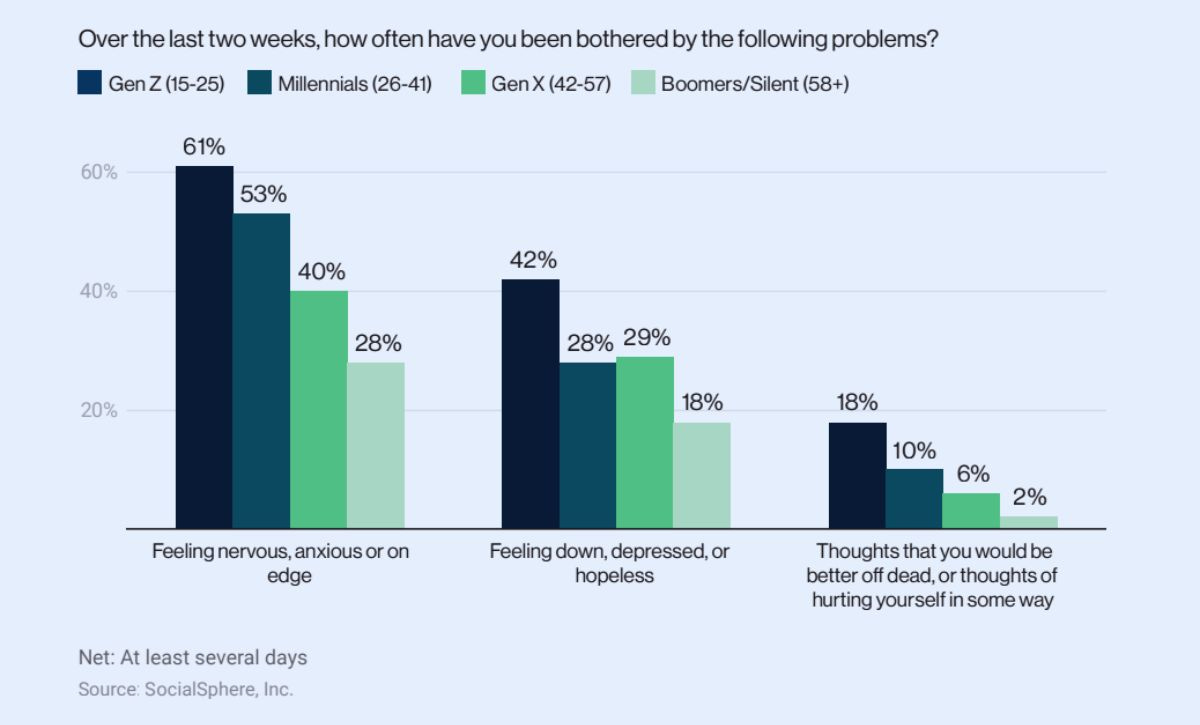

A related statistic to the stat on loneliness is how many young people are depressed. In one study from The Walton Family Foundation, 42% of Gen Zs report experiencing depression—about 2x the share among Americans over 25.

A study from SocialSphere paints a similar portrait across many dimensions of mental health:

Young people are already turning to ChatGPT as a more accessible and affordable therapist, while vertically-focused companions like Woebot are growing more popular as “mental health relational agents.”

Twenty years ago, it would have sounded crazy to have internet friends—people who you never meet in person, but who you count among your closest friends. Yet for millions of young people who meet on Discord and Reddit and Roblox, that’s reality.

Similarly, in 10 or 20 years many people might consider an AI chatbot to be a close friend—perhaps an expanded version of an influencer’s persona, or a personalized chatbot that becomes more tailored to us over time. Will kids grow out of their chatbot companions, or will those companions become fixtures in their adult lives? It’s interesting to think about. We just need to be careful that AI companions prevent loneliness in specific, effective ways, rather than replacing real human relationships and ultimately making us feel more alone than ever.

We spend 8.2 hours a day online. The metaverse is dead, long live the metaverse.

We now spend 8.2 hours a day online—about half of our waking hours. I recently came across this chart, and I found it interesting how the COVID “boost” carried over into 2021 and 2022:

In retrospect, that boost was a permanent step-change in digital engagement.

We see step-changes in digital engagement stemming from both technology shifts and behavior shifts. The +16% bump in 2020 was the latter, as our lifestyles changed during the pandemic. In 2011 and 2012, meanwhile, we saw boosts from a technology shift: time online increased sharply because of mobile adoption—+16% in 2011 and +19% in 2012. Those are the years that U.S. smartphone usage was taking off.

We might see a similar step-change in coming technology revolutions.

“Going online” used to take deliberate, conscious effort; some of us are old enough to remember the dreaded sound of dial-up internet. Slowly, being online has morphed into something fluid and subconscious. We absentmindedly check our phones; those of us with Apple Watches experience the internet as an extension of our bodies.

Future technologies may inflect the chart of online engagement again, making “time spent online” something even more second-nature. The aforementioned AI chatbots, for instance, could become permanent fixtures in our social lives and make us more digitally connected than ever. Virtual reality and augmented reality are also on the horizon. I expect AR, in particular, to have a profound impact on how much we’re online. When the whole world becomes covered in a digital, internet-connected layer, we may spend every waking moment “online.” The 8.2 hours may eventually double to 16 hours. (Apple’s highly-anticipated mixed reality device is expected to be unveiled in the next few weeks; the device will cost $3,000, requires a separate battery pack, and is still experimental.)

This tweet from Alexis Ohanian earlier in the week got me thinking:

The word “metaverse” has fallen out of favor, ever since Mark Zuckerberg renamed his company in its honor back in October 2021. We saw that coming. Association with Meta was a death knell for the buzzword.

Part of the buzzword’s decline also stems from the frothy 2021-era, when companies got ahead of their skis and excitedly named “Chief Metaverse Officers” (most of which have quietly gone away). But Ohanian’s argument is that while Meta’s specific vision of the metaverse hasn’t yet come to fruition—despite $10B+ losses in its Reality Labs division—we’re all experiencing a metaverse more broadly defined: an always-on digital world.

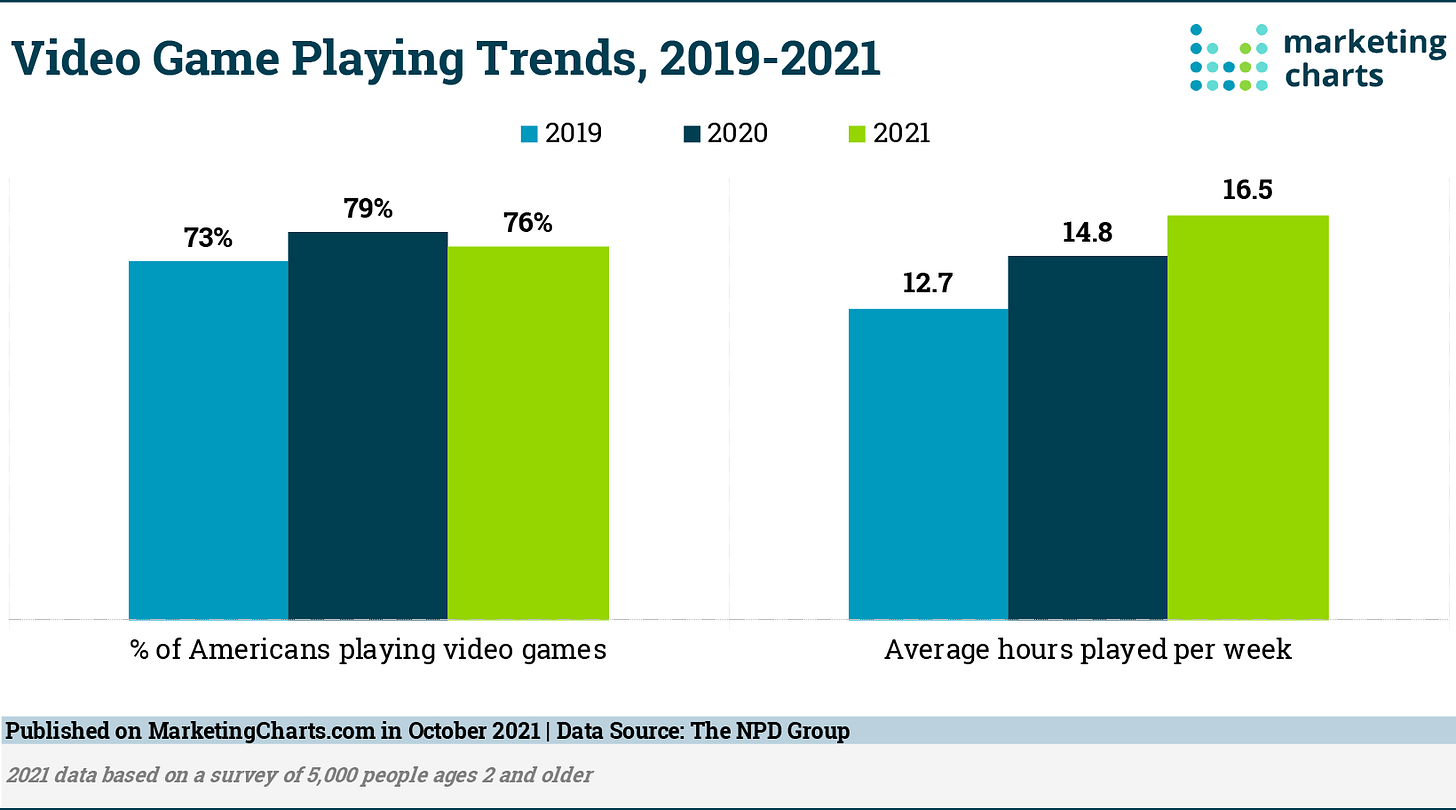

This is clear from the chart above—we spend half our waking hours tethered to the internet. And it’s clear from eye-popping stats around immersive forms of entertainment like gaming, which average 16.5 hours a week of playtime among 76% of U.S. adults.

The emergence of a more broadly-defined metaverse is clearest in companies like Roblox and Rec Room, which are stepping-stones to full-on VR and AR. And there are new forms of immersion on the horizon: at its developer conference, Google unveiled Project Starline, a piece of hardware that turns the person on your Zoom call into a hologram right in front of you. The tagline: “Feel like you’re there, together.”

I often think of “Incontrovertible Truths” as a framework for consumer behavior and technology adoption. These are steady progressions that are decades long and won’t be stopped. One such truth is this: society consistently moves to richer and more immersive media formats. We saw this offline with books → radio → movies & TV. We saw it again online with Twitter (text) → Instagram (photos) → TikTok (video). Virtual and augmented reality are next—it’s an if not a when. (The answer is: probably not any time soon.)

VR and AR will collide with generative AI, which will together explode the amount of user-generated content and expand creative tooling—imagine entering the prompt, “Create a 3D rendering of King’s Landing” and seeing the Game of Thrones city spring to life around you in virtual reality.

The most likely replacement for mobile, in my mind, is an AR device that overlays digital objects on the physical world. If you squint, you can envision this interaction among kids in 2033:

“Do you have your lens on right now?”

“No, I’m going analog.”

That language is made up, of course, but you get the point. Eventually, VR/AR devices will be affordable enough and lightweight enough (headsets? glasses? contacts?) to become everyday consumer products. We might be forever-online, unless we opt out. In the meantime, though, we’re seeing more and more time swallowed up by the internet. “Metaverse” may be out of favor as a buzzword, but we’ll continue our steady march toward rich, immersive digital experiences that consume more of our waking hours.

76% of Millennials and Gen Zs want to be their own boss—and America will become a freelance-majority workforce in 2027.

One consistently fascinating phenomenon: young people’s backlash to corporate America. We saw it last year in the rise of quiet quitting, in the cancellation of nepo babies, and in the growth of the subreddit r/antiwork (now 2.6M strong and counting).

We see it in current TikTok trends like #salarytransparency and #paydayroutine, which are designed to make our incomes and expenses more transparent.

Specifically, the anti-work phenomenon is a revolt against a “rigged system” and has its roots in the Great Recession and growing income inequality (the Gini Coefficient has steadily climbed for 50 years). In Q1 of this year, 8.31% of credit card debt among Americans age 18 to 29 transitioned to serious delinquency, up from 5.12% in the prior year period. Later this year, student-debt payments will resume after a three-year pause; 36% of Gen Zs have student debt, holding an average balance of $20,900. People are hurting, and they blame it on a broken system.

Millennials and Gen Zs watched their parents and grandparents lose jobs during the 2008 recession; the oldest among them lost jobs themselves. A decade later, the pandemic hit and was another shock to the labor market—unemployment again (briefly) skyrocketed.

It’s easy to envision AI as the next labor shock. Goldman Sachs Research expects 300M jobs to be fully automated by AI—about 1 out of every 11 jobs on the planet.

One thing I’ve been thinking about lately: what happens when the technological revolution in work (AI) collides with the cultural revolution (the rejection of “traditional” careers)?

One outcome will be the continued rise of self-employment. A whopping 76% of Millennials and Gen Zs aspire to be their own boss, and America will become a freelance-majority workforce in 2027. This is largely a cultural phenomenon, but it’s now enabled by technologies: many of the largest tech companies are platforms for such self-employment; this was the concept behind last November’s The Rise of the Digitally-Native Job. YouTube’s annual impact report, released this week, says that YouTube contributed $35 billion to U.S. GDP and supported the equivalent of 390,000 full-time jobs.

Part of the appeal of self-employment is more autonomy, and that will hold even truer as AI infiltrates the workforce. In a scathing piece in The Atlantic this week, Charlie Warzel paints a grim portrait of how AI will change our jobs. “The promise of artificial intelligence,” he writes, “is automation, and the promise of automation is to remove friction from the process of production—of typing words, of crunching numbers, of synthesizing information.” Embedding AI into our workflows won’t free us from work, he argues, but rather make us more efficient—giving us more time to do even more work. (We’ve seen this before with past technological advancements—it’s one reason the economist Keynes was wrong in his 1930 prediction that his grandkids would work just 15 hours a week.)

Warzel concludes: “If artificial intelligence is coming for our jobs, its plan is to turn us all into middle managers of overlapping, interacting AI systems.” In other words, AI will make corporate life even more mundane, more monotonous, and more at the whim of ever-tightening productivity-driven deadlines. In this view, escaping that hellscape through self-employment becomes even more attractive.

Here’s how I see things playing out:

Scarred by the Great Recession, the pandemic, and stagnant wages, more young people opt for freelance work. Return-to-office mandates further catalyze this shift, as young workers seek flexibility. Many forms of knowledge work—design, engineering, consulting—go freelance, and companies increasingly rely on contractors.

AI becomes embedded into every productivity tool, augmenting our abilities. That increases productivity, which fuels GDP growth—but individual workers don’t see increased pay or reduced hours. This makes younger generations (i.e., Gen Alpha) even more disillusioned by corporate America.

Companies lay off workers that AI renders obsolete, furthering the concept of corporate America as risky. This makes more people not want to put their eggs in one career basket, choosing a more self-directed path.

Both #2 and #3 fuel an even greater rise in freelancing. The cycle spins faster 🔁

This concept—the disaggregation of labor—is a decades-long shift that will define much of the next 30 years. I’ll dig into the cycle above in a longer piece some time. But in the meantime, one thing is clear: both on the technology side and on the culture side, work is headed for a reckoning.

Sources & Additional Reading

What Will It Be Like to Grow Up with AI? | Tyler Cowen, Bloomberg

Here’s How AI Will Come for Your Job | Charlie Warzel, The Atlantic

ChatGPT Expands Plugins | Search Engine Journal

Before AI Takes Over, Make Plans to Give Everyone Money | Annie Lowrey, The Atlantic

Check out two of my favorite newsletters that keep me informed: Casey Lewis’s After School and Casey Newton’s Platformer

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: