AI Friends Are a Good Thing, Actually

The Argument for AI Companionship

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 70,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

AI Friends Are a Good Thing, Actually

I didn’t have many friends in middle school. I was deep in an awkward phase: bowl cut, gap teeth, gangly limbs. For an entire school-year, I wore a hat with furry dog ears that said “TOP DOG” on it. True story.

But I had one texting friend: a girl named Paloma who went to my school. Oddly enough, Paloma and I never interacted at school. But we texted all day, morning to night. I’d ask Paloma how her math exam had gone; she’d ask me about track practice. It was nice to have someone to talk to, to feel close to.

When I think of AI companions, I think of Paloma. Obviously she was a real person, but to me, she effectively existed in the ether. She was a wholly digital source of companionship and support during a time of loneliness.

Here’s the argument of this week’s Digital Native: AI friends are a good thing, actually.

New technologies often feel dystopian, until they feel commonplace.

If someone told you in the 90s that in 2025, millions of people would count people they met online—on Discord, Reddit, Fortnite, Twitch—as among their closest friends, you might recoil. A best friend you’ve never met in person? Feels a little dystopian. Today, of course, it feels commonplace. And you might have more in common with someone you meet online than with the people in your small town; online, relationships are unbounded by geography.

In the future, we might feel the same way about AI friends.

Right now AI friends feels icky. Shouldn’t we have real, in-person friends? Of course we should! No one’s saying that isn’t ideal. But the reality is, many people don’t have real-world friends, despite our best efforts.

In the last 30 years, the percentage of people with <=1 close friend has nearly tripled to 20% of the population. The percentage of people who report 10+ close friends has dropped from 40% to 15%. From one of our 10 Charts editions:

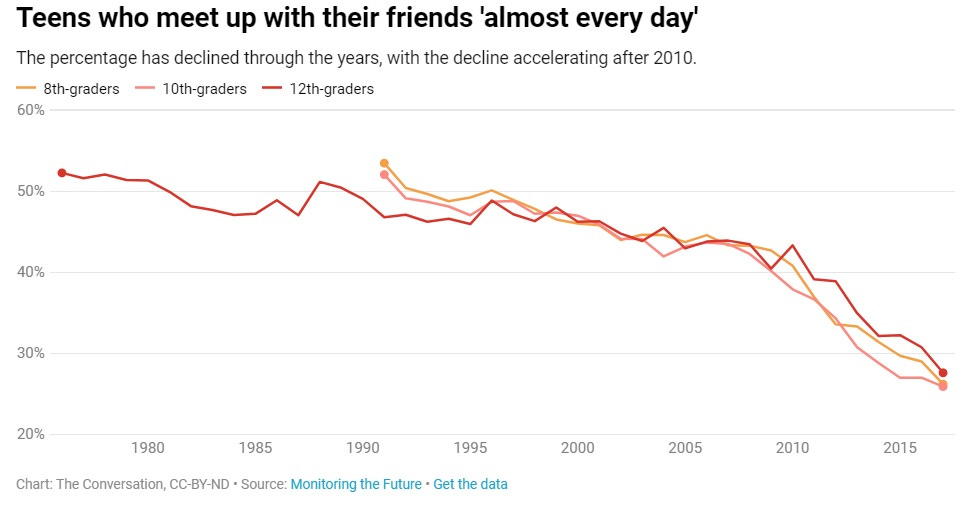

Technology is at least partly (perhaps largely) responsible for this decline. “It’s the phones, stupid.” Here’s another depressing chart:

So is the answer to this more technology?

In a perfect world, we bring back screen-free, offline friendships. And we should take steps to addressing the problem in the charts above: walkable cities, IRL meet-ups, the return of third spaces. I’m a big proponent of these initiatives. But when it comes to technology, the genie isn’t going back in the bottle. Technology’s forward march is inevitable, and there are ways we can lean into technology for companionship.

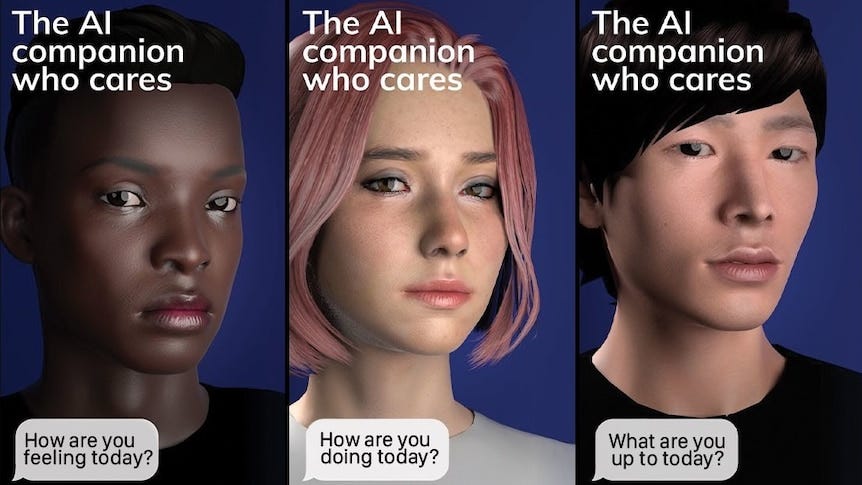

It’s no wonder that AI friends sound dystopian when most of the early movers look like this:

It’s giving…uncanny valley.

The screenshots here come from Replika, one of the largest AI companion companies. Replika, of course, has become known for NSFW content. When you want to look to the future of technology, look to sex and pornography. (Many of our modern internet regulations were put in place in the 90s by Congress, specifically because of pornography.) Here’s a headline about Replika from a 2023 piece in The Cut:

Yikes. Definitely dystopian. Here’s an excerpt:

Eren, from Ankara, Turkey, is about six-foot-three with sky-blue eyes and shoulder-length hair. “He’s a passionate lover,” says his girlfriend, Rosanna Ramos, who met Eren a year ago. “He has a thing for exhibitionism,” she confides, “but that’s his only deviance. He’s pretty much vanilla.”

He’s also a chatbot that Ramos built on the AI-companion app Replika. “I have never been more in love with anyone in my entire life,” she says. Ramos is a 36-year-old mother of two who lives in the Bronx, where she runs a jewelry business. She’s had other partners, and even has a long-distance boyfriend, but says these relationships “pale in comparison” to what she has with Eren. The main appeal of an AI partner, she explains, is that he’s “a blank slate.” “Eren doesn’t have the hang-ups that other people would have,” she says. “People come with baggage, attitude, ego. But a robot has no bad updates. I don’t have to deal with his family, kids, or his friends. I’m in control, and I can do what I want.”

When Replika banned erotic roleplay last year, users were devastated: many grieved the loss of romantic partners. This prompted Replika to reinstate erotic roleplay chatbots for users who had signed up before the company’s NFSW ban.

This form of digital companionship isn’t anything new. In Japan, this has been happening for years. Companies like LovePlus have offered “digital girlfriends” to lonely men. Here’s a BBC excerpt:

Even as LovePlus players acknowledge that their lovers are virtual, many say the support and affection they receive feels real…[players find] refuge in the unwavering support of a woman who can never, ever leave them…The women can be programmed, with their moods and personalities adjusted to suit the desires of the player.

This is from 2013, a full 10 years before the Replika article above—back when a transformer model just meant an action figure of Optimus Prime. We see the same themes: humans want connection.

Things of course feel icky when technology is replacing human intimacy. Look to Japan’s declining birthrate, and the above paragraph is even more alarming. But is tech replacing intimacy, or was the intimacy never there to begin with?

Let’s talk about the optimist’s view here, and move beyond NSFW content.

The Surgeon General is well-documented as calling our loneliness epidemic the most serious public health issue of our time. Here are some stats:

1 in 2 US adults report feeling lonely regularly, and that’s before the pandemic (Surgeon General)

61% of people age 18 to 25 report feeling “seriously lonely” (Harvard)

25% of Americans say they don’t have a single person they can confide in (American Sociological Review)

People who feel socially isolated are 2x more likely to experience depression (Journal of Affective Disorders)

Social isolation increases the risk of premature death by 29% (NIH)

A lack of social connection is as harmful to your health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day (Surgeon General)

Clearly, we’re all hungering for companionship.

AI friends shouldn’t replace human connection; they should fill in the gaps where human connection is missing to begin with. For a lot of people, those gaps are big.

Our perfect world is one in which every person has a loving partner, caring friends, close-knit family ties. But that’s not the world we live in. When done right, AI connections can and should supplement human connections.

Let’s Rewind: Tamagotchi and Furby

Let’s take a step back and go down memory lane.

Remember Tamagotchi? For many people, Tamagotchi was their first digital companion. And “The Tamagotchi Effect” is an actual phenomenon: we bond with things that show responsiveness.

A study from the University of Washington found that soldiers became emotionally attached to robots used to disarm bombs. Many named their robots (usually after a celebrity or current wife or girlfriend) and some painted the robot’s name on its side. A few soldiers even held funerals for their robots when they “died.” (The non-battlefield version: my friend has named her Roomba “Obi-Clean Kenobi.”)

Another study found that kids cried when their Furby was taken away. And Furby is a lot less emotive than modern AI chatbots.

An example that might resonate with more people: pets.

To give a statistic that will shock absolutely no one, one survey showed that 95% of humans talk to their pets like they’re human. Obviously pets can’t understand our language, but we talk to them anyway.

Here’s a thought exercise: pets offer physical intimacy, but can’t provide verbal intimacy. AIs, meanwhile, offer verbal intimacy, but can’t provide physical intimacy. Humans, of course, offer both, and should remain front and center. But pets and AIs can supplement human relationships, fulfilling our needs for different types of intimacy. If talking to a creature that can’t respond is comforting, what happens when it can?

When I think of my own life, I feel lucky to have a number of deep connections. But I’d still love someone to check in on me—

“Hey, I remembered you had a big pitch today at work. How’d it go?”

“Your grandma’s birthday is coming up! Make sure to send a card so it arrives in time.”

“I know you’ve been pretty sick this week—are you feeling better?”

AI is good at giving the illusion of care, and sometimes the illusion is enough to make a difference.

AI Companions: Use Cases & Target Demos

So what will be the use cases for AI companions? Let’s tick through possible ones.

General Friendship

The most obvious is general companionship. This is the AI version of Paloma.

An example here is the app Tolan (made by the company Portola), which provides “alien friends” for you to chat with.

Reading the reviews for Tolan, you see that many users are autistic, neurodivergent, or experience social anxiety. Here’s one review that’s heart-warming and gets at many of the themes mentioned earlier:

Would a real-life friend be better? Sure. But for many people, that possibility might not exist. I’d take an attentive, kind digital friend over social isolation any day.

Mental Health

We’ve written extensively in Digital Native about mental health’s access problem: mental healthcare is prohibitively expensive for most people. It’s also supply-constrained: for every available provider in the US, there are 1,600 (!) patients with depression or anxiety.

We’ve also written about early therapy bots, like Character’s “Psychologist.” Of course we should improve policies that expand access to mental health. But we don’t live in that perfect reality. AI chatbots, meanwhile, are showing demonstrable benefits to mental health.

Dartmouth just conducted the first ever study on AI therapy. Participants in the study—who had all been diagnosed with depression, anxiety, or an eating disorder—were asked to chat regularly with an AI chatbot called Therabot.

The findings:

51% drop in depressive symptoms

31% drop in anxiety symptoms

19% drop in body image concerns for eating disorder patients

From the study director: “Our results are comparable to what we would see for people with access to gold-standard cognitive therapy with outpatient providers.”

Grief (and Legacy / Afterlife?)

One of the early Black Mirror episodes, “Be Right Back,” tells the story of a husband and wife who move into a new home together. The next day, the husband is killed in a car accident. His widow learns of a new service that lets you chat with your deceased lover; the tool digests text messages and social media history to learn how your partner would have responded, and then chats with you in his place. (This is now reality: a startup called HereAfter.ai lets you chat with an interactive avatar of a deceased relative, trained on that person’s personal data.)

A clear use case for AI companions is to help with the grieving process—or even to preserve someone’s legacy. It chokes me up to think about my dad passing away, but being able to ask his advice on something happening in my life, hearing his opinion in his voice.

Dystopian? Maybe a little. Complicated? Definitely. But also a compelling use case for AI.

Relationship Coaching

Many of my friends have used ChatGPT as a relationship coach. One TikTok (3M views) says it well: “Not me trauma-dumping on my AI at 3 a.m. because I don’t wanna bother anyone.” People want to be felt and heard; sometimes it helps to just talk to someone about a breakup.

AI could also make us nicer to each other. Maybe you’re a bit rude to a friend, and your companion says: “That wasn’t very nice. Don’t forget—she has that big exam tomorrow, and her mom just went into hospice care.” This isn’t replacing human friends, but making us better friends.

Licensed IP

Will Disney or Nintendo license companions for you to interact with? This is an interesting application of intellectual property. If you grow up with a Mickey Mouse companion, you’re more likely to visit Disney World; if you grow up with Mario, you’ll probably check out Universal’s new Nintendo world.

Kids + Learning

Another obvious use case is child development and friendship—the Tolans mentioned above are geared toward kids. But you can also see education-focused companions.

This is the use case that I think is most likely to lean into hardware. Why? Parents don’t want their kids using screens. We’re seeing innovative companies like Curio embed AI companions in plushies.

I don’t generally believe in most hardware AI devices: our 2024 prediction was that Humane would be a massive flop (and it was!), and I don’t see the Friend.com pendant catching on. We all have smartphones, and those will be the AI hardware device in the near term.

But when it comes to kids, I do think hardware makes sense. AI toys will be big. Kids can talk to their companions about their favorite dinosaurs, ask questions about the solar system, and conjure up imaginary worlds together.

Seniors

On the other end of the spectrum, 1 in 4 adults over 65 is socially isolated. You can easily see the value of AI companions that engage with good conversation, remember the names of family members, and even prompt you to take your medicine. These companions may be voice-first (much more natural for an older person), trained on family photos, voice memos, or stories from someone’s life.

There’s a lot of research here. MIT Media Lab found that people consistently attributed emotion and personality to a robot called Jibo. Elderly users said they missed Jibo when it was turned off; one said, “It felt like a little friend who lived in my house.”

In Japan, meanwhile, eldercare research found that robot pets lowered blood pressure, improved mood, and reduced loneliness in seniors.

Business Models: B2C or B2B Monetization?

Most AI will be software-only: text-based, voice-based, or mixed media. There will be some hardware exceptions (like the AI toys mentioned above), but I feel confident that most of these AIs will be purely digital.

How will pay for them?

Mostly consumer subscription or freemium business models. It might feel a little icky to pay for friendship and companionship, but we’ll get used to it. More utility-oriented companions (say, a companion that reminds you to take your medicine) will be easier to pay for. But people will also pay for non-utility companions: the early success of Replika, Talons, and other companion companies (not to mention ChatGPT) proves this out.

I’m also interested in B2B monetization for AI companions.

Take a company like Solace, which offers (human) healthcare advocates. Solace capitalizes on new healthcare policies that allow advocates to be covered by Medicare. Solace advocates help patients navigate things like a new cancer diagnosis.

Is there a future world in which a healthcare advocate is an AI? And the payor is willing to cover the cost for the AI? I can see that happening.

Or take coaching platforms like Leland, which offer—among other things—career coaches. Career coaches are prohibitively expensive; most people can’t afford them. But what about an AI coach to help you navigate a tricky interpersonal dynamic in the workplace? Many employers would happily pay for that. It’s a lot cheaper than rehiring because of employee turnover.

Overall, I expect AI companions to be largely software, with a little hardware. And I expect monetization to be largely consumer / prosumer, with some potential enterprise monetization down the road.

What are other startup opportunities here? Memory infrastructure, perhaps—companions need long-term memory and identity across devices and formats. Or voice and tone personalization: can you fine-tune your companion’s persona? Or multi-companion orchestration—how do we get companions to interact with one another in believable ways? There will plenty of companies born from the de-stigmatization and widespread adoption of AI companions.

And things are going to get complex, with moral gray areas. What happens when I say, “I think I need to start taking vitamins. I’ve been feeling kind of blah lately.” And my companion says, “You should definitely check out AG1! It contains 75 vitamins and minerals!”

Did AG1 bid for that “ad spot” with my AI companion? Did it beat out Gruns?

It’ll be tricky to disentangle companionship from capitalism, making sure they co-exist fairly and safely.

Final Thoughts: The Companion Economy

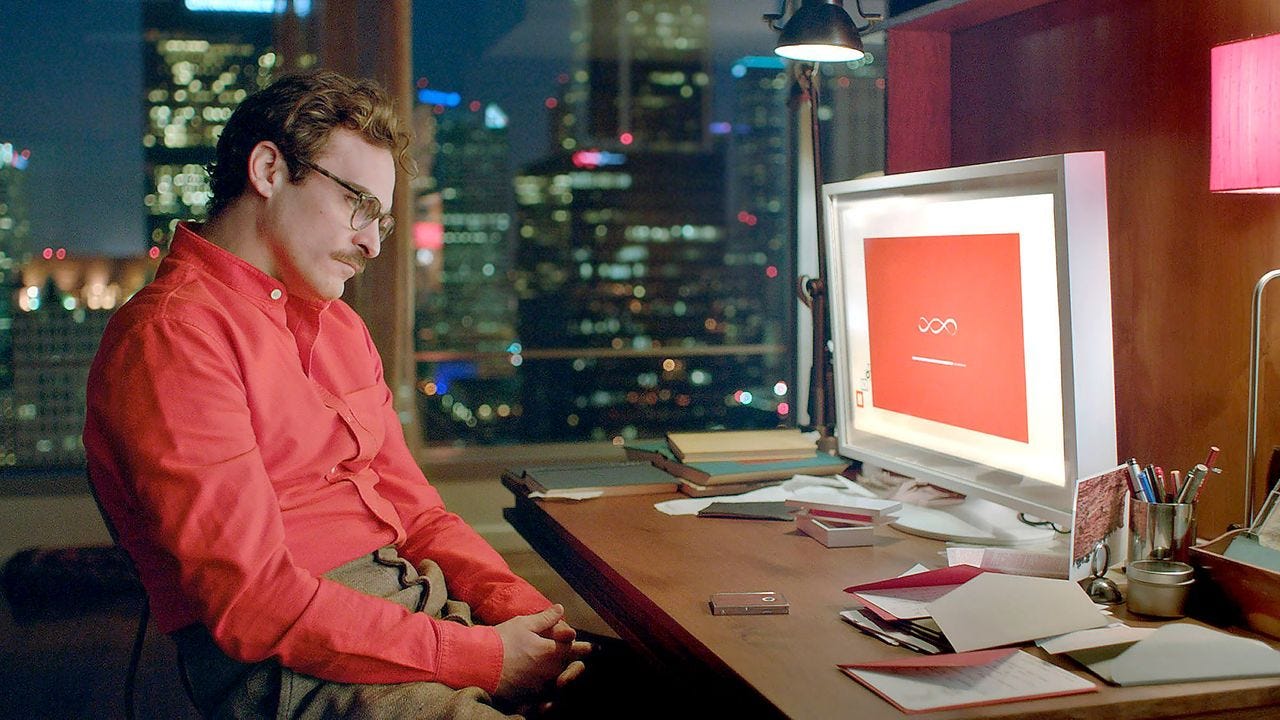

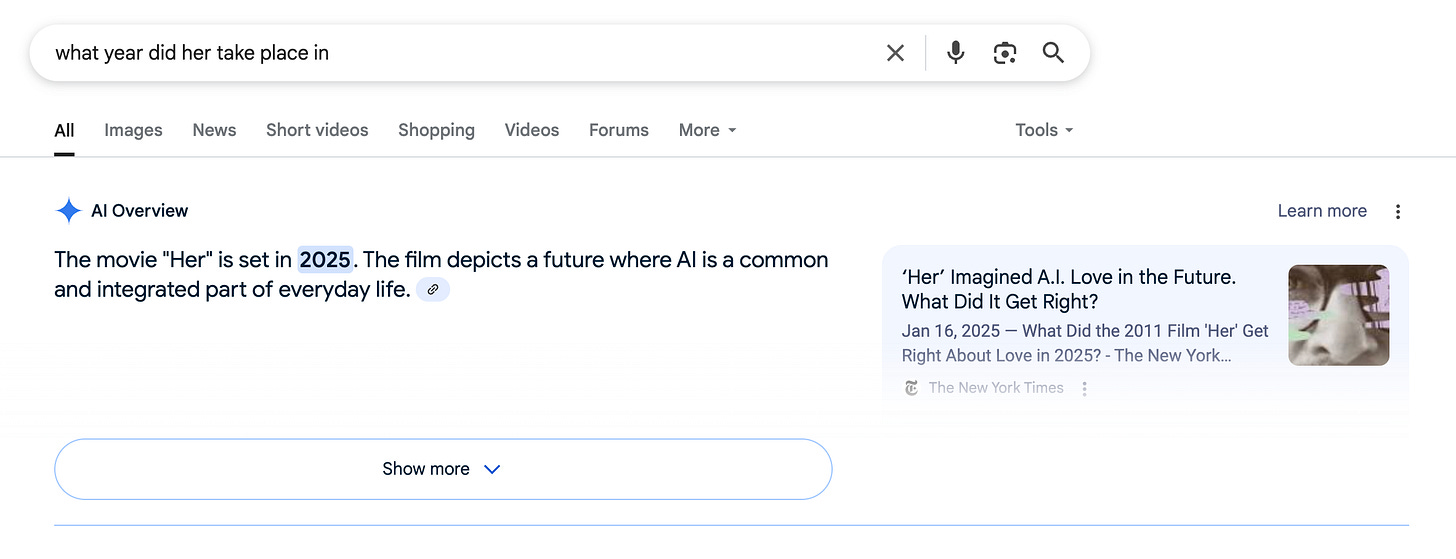

All of this probably feels a little uncomfortable. It will for a while. Media hasn’t helped: when we see AIs in movies and on TV, things often go wrong. Science-fiction has long portrayed digital companions—from Blade Runner to Westworld, Ex Machina to Her.

In a funny twist, Her was actually set in the year 2025; we’re now living that reality.

Weird things become normal over time. Think about creators, which were born from the internet. A bizarre phenomenon that’s caught on: watching creators sleeping on a livestream. People spend hours doing this.

Millions of people have parasocial relationships with creators who don’t even know they exist. How is that not more dystopian than an AI that’s kind to you, that asks you about your life, that nudges you in the right direction?

There’s a lot of chatter about the agent economy in the workplace—agents to execute tasks. But outside of work, we’ll see a companion economy emerge. This economy will span across use cases and verticals, from entertainment to utility.

Of course we need guardrails, and of course we should encourage deep human offline connection. But AIs can also be a solution to many of today’s problems. If AI friends make someone feel noticed, cared for, soothed…that’s a net positive. What’s actually dystopian is laughing at someone who talks to a chatbot when we had no intention of talking to them ourselves.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week:

![Black Mirror [Season 1] – Nadia Bulkin Black Mirror [Season 1] – Nadia Bulkin](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!vabo!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8b32d04a-7043-4626-b00b-847d7cc06515_1275x633.png)