AI in 2023: The Application Layer Has Arrived

Use Cases for Algorithmic Recommendations, Image Models, & Language Models

This is a weekly newsletter exploring the collision of technology and humanity. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Hey Everyone 👋 ,

What’s exciting about AI right now is that the platform layer is solidifying, meaning that it’s time for the application layer to emerge. In other words, the stuff that you and I will interact with every day.

Over the past few months, I’ve written several Digital Native pieces about what’s happening in AI. Given that this is the topic in tech as we head into 2023, I wanted to combine those pieces into one cohesive deep-dive on AI, and then expand upon them.

The result is that this is a longer piece than usual, but my hope is that it offers a “state of the union” snapshot for where we are and a hint at where we might be going.

Let’s dive in.

AI’s Application Layer Has Arrived

When I think about what’s happening in artificial intelligence, I tend to think of two movies. One came out 33 years ago, and one came out 10 months ago.

Hyperland is a mostly-forgotten 1990 film written by Douglas Adams, an author best known for writing The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. The premise of Hyperland (which you can watch on YouTube here) is that Adams is fed up by passive linear TV—what the film calls “the sort of television that just happens at you, that you just sit in front of like a couch potato.”

Seeking a more interactive form of media, Adams takes his TV to a dump, where he meets Tom (played by Tom Baker). Tom is a software agent—essentially, a digital butler capable of personalizing your information and entertainment diet to your specific interests. Tom takes our protagonist through a virtual land of hypermedia—linked text, sounds, images, and videos. In other words, Tom takes Adams on a journey through the internet. (More specifically, through a long and winding Wikipedia-like rabbithole—11 years before Wikipedia would be founded).

Hyperland—and the character of Tom in particular—reminds me of our current reality: AI-powered algorithmic recommendation engines, sculpting a hyper-personalized internet tailored to our unique interest graphs. This is what I’ve referred to as ‘The Tikokization of Everything.’ (David Karpf makes the savvy argument that there’s one key difference between Hyperland and modern day: in the film, you control the algorithms; today, of course, algorithms are optimized to make money for the companies who develop and deploy them.)

The second film I’m reminded of is a more recent creation: March 2022’s Everything Everywhere All At Once, in my mind a sleeper contender for Best Picture at this year’s Oscars. Everything Everywhere is one of the more…chaotic movies in recent memory. The film tells the story of Evelyn (Michelle Yeoh), a Chinese immigrant who runs a laundromat that’s being audited by the IRS. Evelyn soon discovers that she lives in but one universe out of infinite universes, and she must traverse the multiverse in order to save her family.

In many ways, the film acts as a metaphor for the chaos of the internet. In an interview with Slashfilm, Daniel Scheinert, one of the film’s directors, put it this way: “We wanted the maximalism of the movie to connect with what it’s like to scroll through an infinite amount of stuff.”

The YouTuber Thomas Flight (who has an excellent analysis of the film) calls Everything Everywhere one of the first “post-internet” films, capturing the weirdness of online life. One of the fascinating aspects of living in 2023—and one of the guiding themes for Digital Native—is the fact that our brains are no different than they were a century ago (evolution, it turns out, takes a long time), yet our world has changed dramatically in 100 years. As Flight puts it: “We live in a time when more interesting ideas, concepts, people, and places can fly by in the space of one 30 minute TikTok binge than our ancestors experienced in the entirety of their localized illiterate lives.” How does that rapidly-evolving digital chaos warp our slow-to-evolve human minds?

The universes of Everything Everywhere are diverse and deeply, deeply weird. There’s a universe with no human life, in which everyone is a motionless rock. There’s a universe in which everyone is a crayon drawing. There’s a universe in which everyone has hot dogs for fingers (I told you it’s weird).

The movie captures the internet’s kinetic energy and relentless pace.

Yet the movie reminded me less of the internet, and more of what’s happening in generative AI. Just as the film allows its protagonist to translate anything from her imagination into a tangible reality, generative AI allows us to turn our thoughts into words and images and videos.

Here’s what Midjourney produces when I type in the prompt “A person made entirely of fruit”:

Here’s what I get when I type “New York City skyline in the style of Van Gogh”:

I could spend hours (and I have spent hours) experimenting with such prompts.

Generative AI—which broke through in 2022—is the most compelling technology since the rise of mobile and cloud over a decade ago. The platform layer is calcifying, and we’re seeing green shoots of an exciting application layer—the products that could become part of everyday life for billions of people.

The goal of this piece is to examine the “why now” behind this moment in AI, and to explore the ways that startups can build with AI. We’ll cover:

Setting the Stage

Algorithmic Recommendation Systems

Image Models

Language Models

Use Cases for Generative AI

Business Models

Final Thoughts & Key Questions Still to Answer

With that, let’s get to it.

Setting the Stage

Over the past decade, two primary forces have powered technology: mobile and cloud.

Mobile facilitated the rise of large consumer internet companies: Uber and Lyft, Instagram and Snap, Robinhood and Coinbase. Each was founded between 2009 and 2013. Digital advertising rapidly shifted to mobile in the 2010s, and desktop-era companies like Facebook had to scramble to reinvent their businesses.

Cloud, for its part, underpinned an explosion in software-as-a-service (SaaS) and enabled data to become the most prized resource in a business (“Data is the new oil” and all that). Emergent companies—again, each founded between 2009 and 2013—included Slack and Airtable, Stripe and Plaid, Snowflake and Databricks.

The percentage of corporate data stored in the cloud doubled from 2015 to 2022:

Few charts are more impressive than that of Amazon Web Services revenue over the past decade (with 35% profit margins to boot!):

Mobile and cloud made the 2010s a very, very good decade in technology. But over the past few years, we’ve seen a lot of clamoring for what comes next. Virtual reality? Augmented reality? Autonomous vehicles? Crypto? Web3?

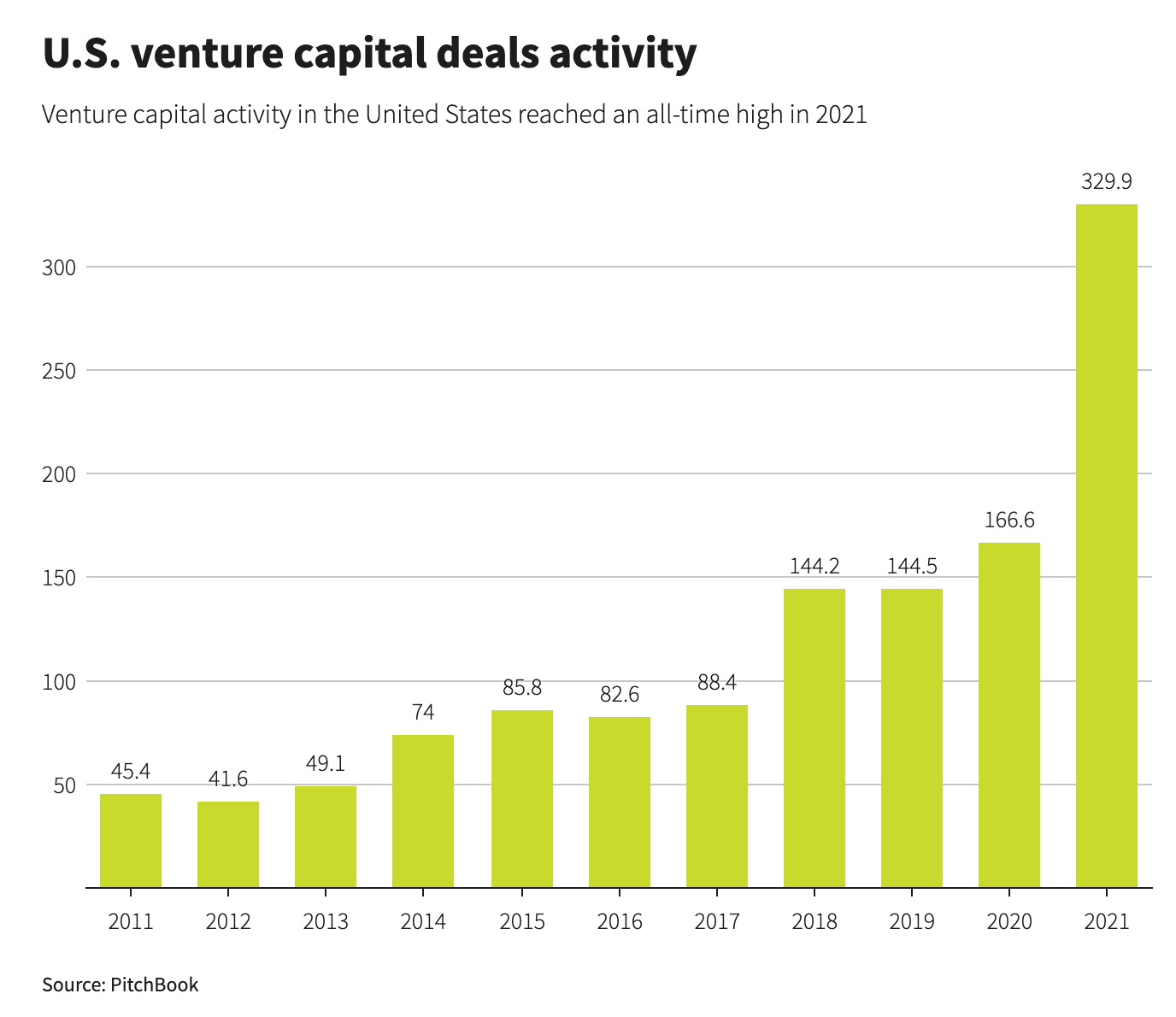

Each is interesting for distinct reasons and within distinct use cases—but each is also very, very early. The entire VR industry is equivalent to just 2% of Apple’s 2021 revenue. (Though perhaps that will change with Apple’s forthcoming mixed reality headset.) Much of the hype surrounding new technologies and vaunted “platform shifts” derives from anxiety around mobile and cloud being…old. AWS launched in 2006; the iPhone came out in 2007. Neither mobile nor cloud are saturated, but they aren’t as ripe for greenfield opportunity as they once were. At the same time, we’ve seen an unprecedented influx of private capital chasing startups:

Perhaps the most compelling—and most likely—force to power tech in the 2020s is artificial intelligence. AI has improved dramatically over the past few years. Until recently, Gmail’s auto-complete sentence feature was almost unusable; now it’s scarily good. Facebook users will recognize how good AI has become at identifying friends in photos; Facebook’s DeepFace engine is now actually better at facial recognition than humans. And just since last summer, we’ve seen the emergence of everything from Stable Diffusion to Midjourney, ChatGPT to Lensa. AI is becoming mainstream.

We’re at an AI inflection point (more on why later) and this inflection point is underpinning a Cambrian explosion in innovation. The years 2009 to 2013 birthed dozens of transformative startups powered by mobile and cloud. The coming years will do the same, with AI this time acting as the catalyst.

Over the holidays, a friend asked me a question: is AI a bubble, or the next big thing? The answer is probably both.

There’s a lot of excitement right now, much of it warranted and much of it probably irrational, premature, or both. But when you zoom out, there’s no doubt that we’re on the cusp of an exciting new era in technology.

Algorithmic Recommendation Systems

Much of the buzz lately has been around generative AI, but “traditional” AI still has a lot of room to run. And perhaps no use of AI is more visible to more people than TikTok’s For You Page, the best modern-day analogue to Hyperland’s prescient ultra-personalized internet.

TikTok pioneered the immersive, algorithmic For You Page to curate content…well, for you. Each posted video is pushed to an initial set of viewers, then evaluated based on how those viewers respond to it—how long they watch, if they like the video, if they comment on it, and so on. If viewers respond well, the video is pushed to even more viewers, and the cycle continues.

I was recently talking with my colleague Martin about what’s coming next in technology after mobile and cloud. We were chatting about AI, and thought back to the famous “Unbundling of Craigslist” graphics from a decade ago.

Here’s a detailed view of Craigslist unbundling:

Here’s a cleaner view of the same concept:

The basic premise of these graphics was that major categories were being reinvented by more focused, better products. Often, the disruptor leveraged a new technology: Tinder, for instance, was one of the first mobile-only dating apps.

A similar reckoning may come from AI applications. Major categories—dating, real estate, job searches—may find themselves completely upended by better use of artificial intelligence. Why swipe endlessly on Tinder when AI can surface your perfect match? A decade from now, we could be looking at a version of the graphic above with a completely different set of logos—AI-first companies that reimagined each category. Generative AI will play a role here, of course, but TikTok-like recommendation systems are also powerful; we’re still in the early innings of our digital worlds becoming more and more tailored to our unique tastes and preferences.

Let’s look at an example—commerce.

SHEIN, in many ways, is TikTok’s sister company. SHEIN and Bytedance (TikTok’s parent company) are both Chinese companies and are two of the world’s three most-valuable startups (America’s SpaceX slots in at #2 to break up #1 Bytedance and #3 SHEIN).

Just as TikTok has infiltrated U.S. media, SHEIN has infiltrated U.S. fast fashion—

Here’s a different view, comparing SHEIN to H&M and Zara sales:

SHEIN’s explosion is nothing short of remarkable: SHEIN has grown over 100% every year for eight straight years (!), and its latest private market valuation makes it worth more than Zara and H&M combined. In June, SHEIN dethroned Amazon as the No. 1 shopping app in the iOS and Android app stores.

SHEIN’s velocity is something to behold: 8,000 new items are added to SHEIN every day, while Zara adds 500 every week. SHEIN is basically an internet-native reincarnation of Zara and H&M, leveraging better technology to squeeze three week design-to-production timelines into three days. SHEIN combs competitor’s websites and Google Trends to figure out what’s in style, then quickly makes its own designs, forecasts demand, and adjusts inventory in real-time.

To bring us back to AI, one aspect of SHEIN that’s impressed me is its recommendations. Just as Bytedance anticipates the content you’ll want to watch, SHEIN anticipates the clothes you’ll want to buy. SHEIN is to commerce what Bytedance is to content.

Over the weekend, I went online shopping for a friend’s upcoming 30th birthday party. The party is Euphoria-themed, meaning you basically come dressed like Maddie or Cassie or Nate Jacobs from the HBO show. I’d never shopped on SHEIN before, but I typed in “men’s mesh black top” to look for a shirt. Then I clicked on the “Pants” category and was met with this screen:

Based only on a single search for that mesh top, SHEIN was able to anticipate pants that were very much the same style and theme. Impressive. (Also, please don’t assume these are the clothes I normally wear.)

In some ways, this is a more sophisticated version of the concept Stitch Fix pioneered with its personal styling subscription boxes. Stitch Fix had humans in the loop, but also leveraged data science based on a lengthy onboarding questionnaire. SHEIN, meanwhile, made spot-on recommendations based on only four words I typed (and likely a lot of data around what I clicked on, where my mouse hovered, and so on).

Stitch Fix’s personal styling market has proven relatively niche, and the stock has gotten clobbered. Active clients are down to 3.9 million, a 200,000-person year-over-year drop (down 5%). The company is pivoting hard to its Freestyle product—a more traditional shopping experience—but that segment is still a small portion of the business.

Though Stitch Fix is struggling, it was on to something groundbreaking—personalized commerce. The company just arrived at the concept a few years too early, when AI wasn’t yet sophisticated enough to take the place of a lengthy questionnaire and small army of data scientists. SHEIN is a step in the right direction, but we’re still only at the cusp of AI-driven recommendations.

Imagine a company that combs through your camera roll and—with stunning accuracy—recommends a new wardrobe for you. Or maybe the company simply asks you to link your Instagram account, and then it digests every like and follow you’ve ever made to deliver incredibly accurate, personalized fashion recommendations.

The major consumer applications of AI will lean heavily into sophisticated recommendations that anticipate your wants and desires before you even know them—in the same way that the TikTok For You Page has shown people that they’re gay before they themselves have arrived at that realization. Perhaps the example company above reinvents commerce in an FYP feed, allowing you to browse one highly-curated item at a time—double-tap to buy, swipe up to see the next item.

The world is shifting to personalization, and AI is the fuel on the fire. I like how my friend Alex puts it:

All of a sudden, a “1-on-1” experience is replicable at scale—and today’s AI applications are still rudimentary compared to those we’ll see in the coming years. Think of every Craigslist category above—education, books, home decor. Each one is ripe for reinvention.

Image Models

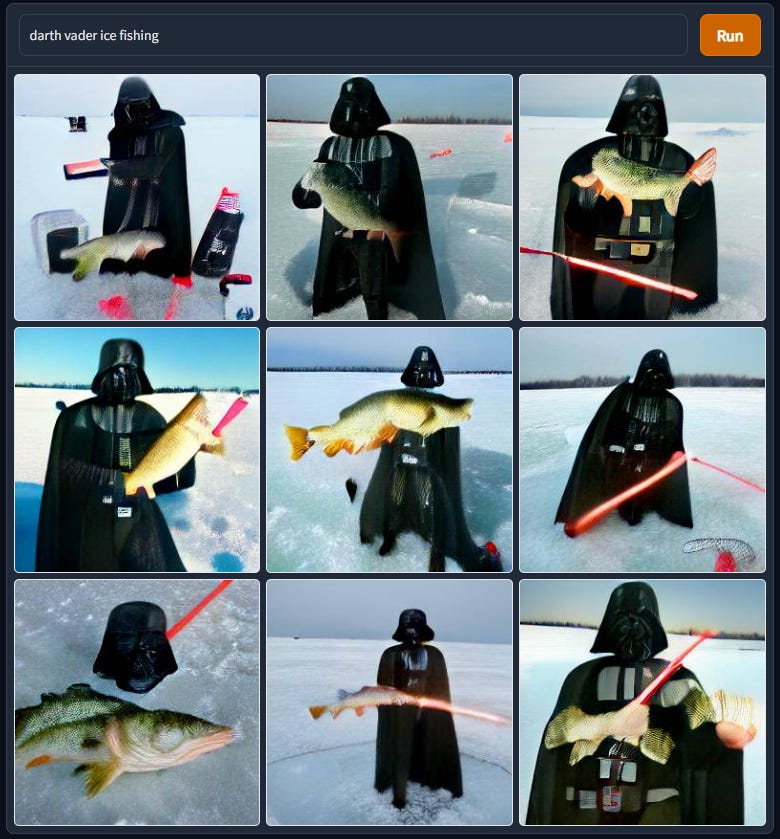

Text-to-image generative AI exploded in 2022. First on the scene was DALL-E from OpenAI (the name is a portmanteau of the artist Salvador Dalí and Pixar’s WALL-E). Not everyone could access DALL-E, but creations began to make their way across the internet; my favorite is the Twitter account Weird DALL-E Generations.

To much of the world, DALL-E was the first true “wow” moment with AI. Speaking with MIT, OpenAI’s Sam Altman credits this fact to the emotional power of images:

I would say the tech community was more amazed by GPT-3 back in 2020 than DALL-E. GPT-3 was the first time you actually felt the intelligence of a system. It could do what a human did. I think it got people who previously didn’t believe in AGI [artificial general intelligence] at all to take it seriously. There was something happening there none of us predicted.

But images have an emotional power. The rest of the world was much more amazed by DALL-E than GPT-3.

People tend to prefer richer media formats: Instagram (primarily photos) has always been more popular than Twitter (primarily text); TikTok (primarily videos), meanwhile, has been eating away at Instagram usage, forcing the latter to pivot to video with Reels. The same preferences, in my mind, will hold true for generative AI: images > text, soon video > images, and eventually immersive 3D experiences > video. (This truth on consumer preferences is also the reason I continue to be long-term bullish on VR and AR.)

After DALL-E got things started, Stable Diffusion and Midjourney came along last summer and shook things up. Stable Diffusion was groundbreaking in that it was open-source, meaning developers could build on top of it. To get technical, Stable Diffusion moved diffusion from the pixel space to the latent space, driving a profound increase in quality. (More on that here if you’re interested.) Midjourney, meanwhile, was groundbreaking in how accessible it was. Midjourney exists on Discord: anyone can sign up for a free account and get 25 credits, with images generated in a public server. (You can join the Discord here.) After you exhaust your 25 credits, you pay either $10 or $30 a month, depending on the number of images you want to create and whether or not you want them to be private to you. Midjourney has rapidly become one of the most popular servers on Discord (perhaps the most popular server?) with 7.4 million members. (I believe that the Genshin Impact server, with ~1M members, previously held the crown as top server, but I could be wrong on that.)

You can see here how Midjourney, DALL-E 2, and Stable Diffusion each have slightly different styles when using the same text prompt:

The below timeline, meanwhile, gives a broader appreciation of how AI image generation has improved over the past decade (notice both the growing complexity of the prompts in recent years, and the improving fidelity of the outputs):

Last year was a tipping point for image models, with rapid improvements in quality. One example: famously, AI is bad at making hands. It’s very difficult to know how many fingers have already been made unless the AI has an excellent sense of context. The result is that we end up with lots of four- and six-fingered hands. In the below side-by-side of Midjourney v3 (July 2022) and Midjourney v4 (November 2022), you see marked improvements: we no longer have a penguin with two beaks and a penguin with three legs.

When I think of the early challenges of image generation, I think back to the early challenges of animation a century ago. One of the reasons that Mickey Mouse wears gloves is that it made for much faster animation; hands are difficult to draw. The same goes for Fred Flintstone and George Jetson—neither has a visible neck, because allowing for a neck meant that a character’s entire body needed to shift with each movement and expression. That meant a lot more work for the animator. A necktie and a high collar offered tricks for animators to speed up production.

Half a century later, of course, animation has come a long way. Finding Nemo was in some ways an excuse for Pixar to show that it could animate realistic water. Ditto for Monster’s Inc. and fur. Pixar waited until The Incredibles, its 6th feature film, to tell its first story about humans because CGI technology hadn’t previously been ready (part of the reason Toy Story focused on toys was because Pixar couldn’t yet render detailed humans—you barely see Andy and his mom in the film).

The arc of digital creation is following a similar path to the arc of animation, but the pace of improvement in technology is only increasing. The difference between the Midjourney images of penguins above, for example, was the result of just a handful of months.

Language Models

In the Black Mirror episode “Be Right Back”, a husband and wife move into a new home together. The next day, the husband is killed in a car accident. His widow learns of a new service that lets you chat with your deceased lover; the tool digests text messages and social media history to learn how your partner would have responded, and then chats with you in his place. The plot of this episode (which came out in 2013) is now reality. A startup called HereAfter.ai lets you chat with an interactive avatar of a deceased relative, trained on that person’s personal data.

Last year saw a leap forward in language models alongside the leap forward in image models. In November, OpenAI released ChatGPT, which gained 1 million users in the first five days after release. ChatGPT is incredible; using it is a “magic moment” in technology akin to your first time using Google Search. (Every time I use ChatGPT, I’m reminded of the Arthur C. Clarke quote: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”)

A few examples below of what ChatGPT can do:

Prompt: “What are wormholes? Explain like I am 5.”

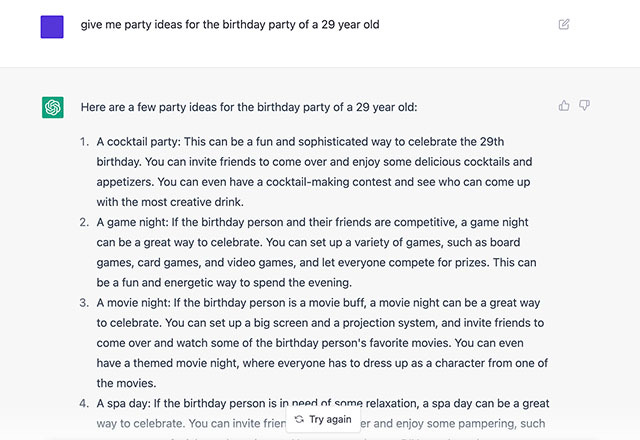

Prompt: “Give me party ideas for the birthday of a 29-year-old.”

Prompt: “Write a song on working from home with accompanying chords.”

The modern pace of development and adoption of AI can be traced to a seminal paper published by Google in 2017, Attention Is All You Need. The paper, co-authored by Aidan Gomez, founder of Index portfolio company Cohere.ai, catalyzed an era of “transformer” models that have grown exponentially in size.

While GPT-3 came out less than three years ago with ~200 billion parameters, the new GPT-4 has ~1,000,000,000,000 (a trillion) parameters.

Here’s a more entertaining view, courtesy of Andrew Reed:

Each new model makes leaps forward in its ability to come up with new ideas, understand context, and recall information. But larger models are also much, much more expensive to train. Training a model with hundreds of billions of parameters can cost millions of dollars. For this reason, big models are becoming the foundations upon which startups build. My colleague Erin Price-Wright draws the analogy to Amazon’s AWS or Microsoft’s Azure—cloud computing platforms upon which millions of businesses rely.

As an example, many startups build on OpenAI’s GPT-3. Jasper, for instance, provides an AI copywriter powered by GPT-3. Starting at $29 / month / seat, Jasper gives you writing superpowers. Yet Jasper was taken aback by OpenAI’s release of the free ChatGPT, which it worried would cannibalize its business. (The Information has some terrific reporting on the Jasper-OpenAI relationship.) The dynamic between foundational models and the companies building on them will be interesting to watch play out this year.

Use Cases for Generative AI

One of the earliest forms of AI was handwriting recognition, used primarily by the postal service to read addresses on envelopes. But that use case of AI is incredibly specific. When it comes to generative AI, we’ve seen: 1) massive improvements in image and language models, and 2) valuable infrastructure provided by companies like OpenAI, Hugging Face, and Stability.ai. Those two factors combine to broaden the possibilities of use cases.

I like how Nat Friedman framed the opportunity in a conversation with Daniel Gross and Ben Thompson:

When people hear about getting involved in AI and large language models, they assume a lot of specialized knowledge is needed. In order to work with these things I have to know deep learning and gosh, I probably have to know calculus or at least linear algebra, and I’m just sort of not into that sort of thing. Do I need to know how to program CUDA kernels for Nvidia hardware? It’s intimidating.

And what I think they’re missing is that I think this is a fallacy, and I think the fallacy is sort of saying, gosh, to make paint you have to be a chemist. And so if I want to be a painter, I have to learn chemistry. And the reality is you can be a great painter and not know anything about making paint. And I think you can build great products with large models without knowing exactly how they’re made.

I love that analogy. It’ll become easier for anyone to build tools that harness AI—to paint. Every industry is ripe for change.

One dramatic oversimplification is that use cases can be grouped into two buckets: 1) Creativity, and 2) Productivity.

When it comes to creativity, we see generative AI lowering barriers to creation. With Midjourney, you can make concept art for a movie. Companies like Latitude.ai create games like AI Dungeon that leverage GPT-3 for AI-powered exploration. Alpaca, meanwhile, took Twitter by storm with the demo of its Photoshop plug-in; the company’s mission is “to combine AI image generation power with human skill.”

I’ve written in the past about the growing accessibility of creative tooling. Back in 2015, Steven Johnson wrote in The New York Times:

The cost of consuming culture may have declined, though not as much as we feared. But the cost of producing it has dropped far more drastically. Authors are writing and publishing novels to a global audience without ever requiring the service of a printing press or an international distributor. For indie filmmakers, a helicopter aerial shot that could cost tens of thousands of dollars a few years ago can now be filmed with a GoPro and a drone for under $1,000; some directors are shooting entire HD-quality films on their iPhones. Apple’s editing software, Final Cut Pro X, costs $299 and has been used to edit Oscar-winning films. A musician running software from Native Instruments can recreate, with astonishing fidelity, the sound of a Steinway grand piano played in a Vienna concert hall, or hundreds of different guitar-amplifier sounds, or the Mellotron proto-synthesizer that the Beatles used on ‘‘Strawberry Fields Forever.’’ These sounds could have cost millions to assemble 15 years ago; today, you can have all of them for a few thousand dollars.

This is remarkable, and it continues to hold true: Parasite, the 2020 Best Picture winner, was cut on Final Cut Pro. Tools are progressively becoming more affordable and more accessible, crowding in more creation.

AI broadens what’s possible. Imagine Roblox Studio powered by AI, or what AI can unlock when combined with Figma. It’s now been over two years since I made this graphic:

YouTube was revolutionary, but left barriers to creation: 1) the money to invest in expensive tools, and 2) the knowledge of how to use those tools. TikTok removed those barriers with no-code-like tools, leveling the playing field. The result is that 1 in ~1,000 people on YouTube create content, while closer to 60% of TikTok users create.

Perhaps this year, this graphic can be updated with a third box—an intuitive, powerful tool that goes beyond no-code creation tools and leverages generative AI in the process of making content. Dream up photos for Instagram, videos for TikTok, or content for a de novo social network.

Just as AI amplifies creativity, AI amplifies productivity. We see this in the tools that give writers and marketers superpowers, like Jasper.ai, Copy.ai, and Lex. I asked ChatGPT to help me brainstorm new taglines for Digital Native, and its suggestions were impressive:

We see the productivity gains in Gong, which uses AI to help B2B sales teams be more efficient and effective. We see them in Osmosis, which helps ad agencies generate AI ads. We see them in GitHub Copilot, which turns natural language prompts into coding suggestions across dozens of programming languages, and which became generally available to all developers in June 2022. (Copilot now generates about 40% of code in the projects where it’s installed, headed to 80% within five years.)

The early targets of AI (particularly built on language models) will be rote, repetitive tasks. One area I see ripe for reinvention: customer support. These are the areas where today’s AI can already make serious inroads. More complex tasks (3D game creation comes to mind) will come further down the road. But any industry that involves human creation (read: basically every industry) will feel the effects of AI.

I’ve seen a few comparisons between early AI apps and early iPhone apps. Remember the flashlight app, the lightsaber app, the lighter app? Remember Fruit Ninja and Tap Tap Revenge? We’re in the very early innings of applications, and it’s too early to tell what the killer apps will be. A looming question mark is how companies will build competitive moats; true tech differentiation is rare, and companies will need to find ways to stay ahead of competition, perhaps with network effects or with iterative loops of user engagement and product refinement. After all, it turned out that 2008-era flashlight apps didn’t have much of a moat.

But just as in a few years we evolved from the lightsaber app to Uber and from Fruit Ninja to Instagram, the ecosystem will evolve rapidly and sustainable, differentiated, generational companies will emerge.

Business Models

Software-as-a-Service is a beautiful thing. Predictable, recurring revenue. 80%+ gross margins. Ideally net dollar retention >100%, meaning that even without acquiring any new customers, your business steadily grows year-over-year. (140% NDR implies that with zero new customers, you will grow revenue 40% YoY).

My hunch is that many of the best AI startups will be SaaS companies. Why change a good thing?

Runway, for example, is one of the most exciting AI companies out there. Runway offers an AI-powered creation suite, and seeing a product demo is jaw-dropping. You can get a sense for some of the product’s magic from videos like this one:

In that video, Runway offers text-to-video generation, conjuring up a city street and then letting the user quickly make changes (e.g., remove a lamp post, or make the video black and white). Imagine you work in special effects in Hollywood—Runway lets you add an enormous explosion in seconds, something that would take tremendous time and money sans AI. CBS is a customer, using Runway to cut its editing time on The Late Show from five hours to five minutes. New Balance is a customer, using custom Generative Models on Runway to design their next generation of athletic shoes.

Runway pricing will look familiar to any SaaS enthusiast:

We’re also seeing AI companies turn to other familiar business models. Midjourney leans on consumer subscription. Lensa, which took the world by storm in December, offers freemium pricing + micropayments. It cost me $8.99 for a 50-pack of custom avatars. (Side note: Lensa is a classic example of a product tapping into people’s vanity, and harks back to last year’s Digital Native piece The Seven Deadly Sins of Consumer Technology.)

The challenge with Lensa, of course, is defensibility; Lensa lives on top of Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok and will have to figure out how to develop a moat. (The same issue may apply to SaaS companies building on foundational models, as we saw earlier with Jasper vs. ChatGPT.) That said, maybe Lensa doesn’t care about a moat—the company reportedly made $40-50M in just a few weeks. There will be many AI applications that will be profitable and meaningful for their developers, without needing (or perhaps wanting) to be venture-scale outcomes.

One creative new company building with a familiar business model is PromptBase. PromptBase is a marketplace for text-to-image prompts—likely one of the first marketplaces in generative AI. It’s surprisingly difficult to come up with the right prompt to produce a stunning piece of AI art. The most beautiful pieces often stem from detailed prompts, and writing the prompt is itself a craft. Here’s an example prompt for a Stable Diffusion image:

A distant futuristic city full of tall buildings inside a huge transparent glass dome, In the middle of a barren desert full of large dunes, Sun rays, Artstation, Dark sky full of stars with a shiny sun, Massive scale, Fog, Highly detailed, Cinematic, Colorful

PromptBase sells access to such long, highly-specific prompts. The marketplace has 11,000 users so far.

The short answer for business models in AI applications is that we’ll likely see the same go-to business models that have powered tech (and business writ large) over the last generation. There will be ad-driven social networks, micropayment-driven MMOs, usage-based pricing. Marketplaces will likely (again) prove to be more capital intensive to scale, but will (again) have powerful network effects that provide strong moats. And SaaS will (again) prove to be among the most desirable business models, though AI SaaS companies will need best-in-class products to cut through the noise of how crowded enterprise SaaS has become.

Final Thoughts & Key Questions

When a technology changes how a broad range of goods or services are produced, it’s called a “general-purpose technology.” The team at Our World In Data argues that there have been two major general-purpose technologies for humans: 1) the Agricultural Revolution, which gave us food production at scale and let us transition from hunting and gathering to farming; and 2) the Industrial Revolution, which gave us manufacturing at scale. I’d argue that the onset of the internet—the Digital Revolution—marked a third. But I also agree with them that Transformative AI is the next general-purpose technology:

This is an exciting moment. Overhyped? Perhaps a little. But that hype will also attract the talent that will push forward the field; in some ways, it’s self-fulfilling.

AI isn’t going anywhere. We need to figure out how to live with AI and leverage it to amplify human abilities. Schools are struggling to figure out how to handle ChatGPT, with many opting to ban them. But I agree with the Wharton professor Ethan Mollick, who argues, “Large language models aren’t going to get less capable in the next few years. We need to figure out a way to adjust to these tools, and not just ban them.” Today’s kids will live in a world teeming with AI; they need to understand how to navigate that world.

Of course, there are major ethical issues to work out—leaps forward in technology often walk a fine line between deeply-impactful and dystopian. Among the questions we need to figure out:

Who is responsible for AI’s mistakes?

Who is the creator of an AI work? Is it the AI? The developers? The person who wrote the prompt? The people whose work was used to train the model?

How do we determine what’s human-made vs. machine-made? Where does the line that separates the two even exist?

How do we get rid of AI bias?

How do startups differentiate themselves and build a moat?

Where will value accrue in the ecosystem, and how should value creation be distributed?

Will AI be a net job creator or a net job destroyer? How do we retrain workers who are displaced by AI?

There’s still a lot to figure out. Massive technological advancements often cause massive social discord, debate, and even conflict. That’s the pessimistic view.

But I’m a perpetual tech optimist, and this is also an exciting moment—as long as we put the right safeguards in place. I’ve used this quote from Midjourney’s David Holz before, but I like how it frames the opportunity:

We don’t think it’s really about art or making deepfakes, but—how do we expand the imaginative powers of the human species? And what does that mean? What does it mean when computers are better at visual imagination than 99 percent of humans? That doesn’t mean we will stop imagining. Cars are faster than humans, but that doesn’t mean we stopped walking. When we’re moving huge amounts of stuff over huge distances, we need engines, whether that’s airplanes or boats or cars. And we see this technology as an engine for the imagination. So it’s a very positive and humanistic thing.

An engine for the imagination.

I’m sure I’ve made glaring oversights in this piece, and I’d love to hear them. I’d also love to be challenged on which use cases and business models will come first and which will ultimately be most valuable. Shoot me an email or find me on Twitter (@rex_woodbury).

One exciting thought to end on: generative AI will soon collide with other maturing technologies, such as VR and AR. Imagine text prompts that generate immersive, three-dimensional virtual worlds. That will likely be a possibility before too long. Technology often moves quickly: within a single lifetime (63 years) we went from the Wright Brothers’ first flight (1903) to putting a man on the moon (1969), 239,000 miles from Earth. Within the lifetime of someone born today, we’ll see every part of human life, work, and society reinvented by AI.

Subscribe here to get Digital Native in your inbox each week:

Thank you to thought partners on all things AI, including my Index partners Martin Mignot, Erin Price-Wright, Mike Volpi, and Cat Wu.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Terror of Everything Everywhere All At Once | Thomas Flight

Money Will Kill ChatGPT’s Magic | David Karpf, The Atlantic

The Best Little Unicorn in Texas: Jasper AI and ChatGPT | Arielle Pardes, The Information

AI’s Impact | Our World in Data

Some of my colleagues at Index wrote several great pieces on AI, including deeper dives into technical aspects | Bryan Offutt, Erin Price-Wright, Kelly Toole, Mike Volpi, Cat Wu

Generative AI | Sequoia Capital’s Sonya Huang and Pat Grady

Jeremiah Lowin and Patrick O’Shaughnessy (podcast)

Thank you to David Karpf and to Thomas Flight for making me view Hyperland and Everything Everywhere in more nuanced and interesting ways

How TikTok Holds Our Attention | Jia Tolentino, The New Yorker

A deep-dive into SHEIN | Green Is the New Black

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! See you next week.