AI's Communication Revolution: We're All Talking to Computers Now

OpenAI GPT-4o, Chatbots, and a Framework for Digital Communication

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 60,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

AI's Communication Revolution: We're All Talking to Computers Now

On Monday night, I rewatched the movie Her.

The reason? Watching OpenAI’s Monday demo of GPT-4o (that’s an “o,” which stands for “omni”) made me think Her was worth revisiting. And it was—10 years since coming out, the movie remains as prescient as ever.

GPT-4o can reason across audio, vision, and text in real time. What does that mean? In its launch video, an OpenAI employee asks GPT-4o to guess what he might be doing. The AI takes in the room, observing that the employee is wearing an OpenAI hoodie and microphone. She hazards a guess—he must be filming an important event, perhaps a product launch related to OpenAI? He delivers the punchline, telling her that she is the product launch. The 1:22 demo video is worth watching in full.

Comparisons to Her quickly became widespread; the top comment on OpenAI’s TikTok video reads:

Later on Monday, Sam Altman acknowledged the similarities:

Her, of course, tells the story of a man (played by Joaquin Phoenix) who falls in love with an AI (voiced by Scarlett Johansson). Science fiction will soon be reality.

The internet’s revolution was communication with any person. Networks of people to people. AI’s revolution is communication with AI. Networks of people to machines. The internet facilitated human-to-human connections using computers, and AI facilitates human connections with computers.

Both are revolutions in communication—just of a different sort.

I’ve shared the image below before. It was created in 2021 by Barrett Lyons, who used Border Gateway Protocol routing tables to visualize internet networks. In the image, we can see clusters of network regions—examples of clusters include the U.S. Department of Defense’s Non-Classified Internet Protocol Network, Shenzhen Tencent Computer Systems, and Amazon’s AWS.

You can imagine a similar visual in 10 years time, mapping human communications with artificial intelligence. We’re going to be talking to AIs—a lot.

Agents, copilots, chatbots. Call the AIs what you want. I suspect the terminology we use will differ based on use case:

Agents will carry out work, a new employee handling our grunt work.

Copilots will augment our work, suggesting a new sentence or a new line of code.

Chatbots, meanwhile, will give us someone to talk to, fulfilling our human longing for connection.

Something I think about often: the amount of human communication, and how its composition has shifted over time. Imagine a breakdown of words that humans speak to one another; how has that mix been divided between in-person communication and virtual communication over time?

I imagine the chart looks something like this:

We still talk a lot in person, but we also talk a lot using technology. Human send 12M iMessages, 2M Snapchats, 146K Slacks, and 575K tweets every minute.

I expect we’re about to talk a lot more—and not just to each other, but to computers. Pull forward the chart 20 years, and it might look something like this:

Obviously this is oversimplified. But it’s an important shift. That salmon-colored portion birthed some of the largest companies of the last generation—Facebook and Slack and Discord and Snap. What companies will be born from the light blue portion?

In early-stage startup markets, we see innovation across all forms of communication. Before AI, we saw four core forms of communication; AI now adds a fifth.

IRL

Bilateral

Parasocial

Many-to-Many

AI-Centric

Let’s tick through innovation happening in #1 - 4, then explore what’s coming in #5.

1) IRL

These are the technology companies that enable offline “in real life” interactions.

An example might be Live Nation (which owns Ticketmaster)—name a company that was harder hit by COVID but rebounded more strongly:

Eventbrite is another example for IRL, a venture-backed company that’s now public with a ~$500M market cap. In 2023, the ticketing platform brought in $326M in revenue, +25% year-over-year, on the back of 302M tickets sold across 5.2M events.

We see a few challengers in the Seed and Series A markets. Partiful has grown nicely—events have good built-in virality—and now seems the default for events in major markets (certainly in New York City). Luma is another Eventbrite-disrupter, and Bounce has gotten good traction on college campuses.

The challenge is monetization.

It’s tough to get people to pay for event platforms; Paperless Post is a nice business, but hardly a venture-scale outcome. Jury’s out on whether “IRL” startups can mature into sticky products that bring in meaningful revenue.

2) Bilateral

We often forget that WhatsApp was one of the biggest venture capital success stories of all time.

Sequoia led WhatsApp’s $8M Series A (remember the days of an $8M Series A?), and doubled down with a later $50M Series C. When Facebook bought WhatsApp for $19B in 2014, Sequoia’s stake was worth ~$3B. That deal remains the largest acquisition of a venture-backed company in history; Figma stole that crown last year, but the blocked Adobe acquisition hands the crown back to WhatsApp.

The Facebook acquisition took place when WhatsApp had 450M users. Today, WhatsApp has 2.96B active users, passing the 2B threshold in February 2020. The app is forecast to hit 3.14B users by 2025.

Many Americans begrudging use WhatsApp for international friends and group chats with non-Americans. But, finally, WhatsApp is catching on in the U.S. Active users were up +9% last year, and Gen Z in particular seems to be taking to the app. On its current trajectory, WhatsApp may even challenge iMessage as America’s top-messaging app—a once-unthinkable outcome. Part of the reason: WhatsApp is more egalitarian for Android users and offers a better chat experience for iPhone users. (I’m having nightmares thinking about receiving “X Friend Likes Your Message” as a text.) I’d be curious the math happening at Apple: does (1) value creation from the blue text lock-in outweigh (2) value leakage from a worse chat experience?

“Bilateral” is what I call the companies that underpin one-to-one interactions. Of course, WhatsApp, iMessage, and others also facilitate group chats—but the apps are primarily used for smaller, more intimate messaging amongst friends and family.

Few upstart chat apps have gained traction, and this category has almost-insurmountable incumbent network effects. I don’t expect much innovation here.

3) Parasocial

Parasocial relationships are one-to-many relationships. These relationships existed before the internet—movies, TV, celebrity culture—but the internet supercharged them. We all have a few influencers who we know intimately—what they eat, what they wear, what’s in their bathroom cabinet—yet these people have no idea we even exist.

Platforms typically underpin parasocial communication. There are the big ones like YouTube and Instagram, sure, but also more nascent ones like Substack—writing Digital Native to your inbox is a form of parasocial communication. It’s rare for the actual underlying networks for parasocial to see much innovation or disruption.

More innovation is occurring in the ecosystems and economies surrounding parasocial relationships. These are often interesting business models. To take three examples:

Anycolor is a Japanese company that powers vTubing—the concept of building parasocial relationships through a virtual, often anime personality. (The term “vTuber” comes from “virtual YouTuber.”)

Last year, Anycolor grew revenues +79% from $90M to $160M, while growing net income 140% from $18M to $43M.

Flagship, one of our companies at Daybreak, lets anyone with an online following run a boutique online storefront for their community. Under the hood, Flagship is end-to-end commerce infrastructure that makes the business of running a retailer turnkey for a new generation of small business merchants.

And Stan allows creators to monetize their parasocial relationships through a Swiss Army knife of options—digital products, coaching sessions, creator courses, and so on.

Stan, which was founded in 2020, grew last quarter from $15M ARR to $27M ARR.

Parasocial relationships are arguably the form of human connection most propagated by the internet, and we’re still seeing the tools and platforms built to underpin this new form of interaction.

4) Many-to-Many

When I think of this category, I think of a beehive, humming with activity. These are the Discord servers and subreddits and Twitch streams built around every possible interest under the sun.

We haven’t seen as much innovation in Many-to-Many within Consumer lately, but we see some within Enterprise. Two of the biggest “community” startups are Figma and Notion, both of which have smartly cultivated their communities over the years. (Last year’s How Notion Used Community to Scale to 20M+ Users, which turned one this week, dug into Notion’s community growth strategies with its Head of Community, Ben Lang.)

We’ve even seen enterprise tools emerge to help companies manage their communities. Common Room, for instance, lets teams keep a pulse on signals across the web.

Open-source communities are also robust in many-to-many interactions; their entire concept is built on this premise.

5) AI-Centric

Stack Overflow is a “Many-to-Many” platform—a place for developers to learn to code and to share their learnings. This week, Stack Overflow developers weren’t too thrilled about the platform striking a deal with OpenAI; many developers are sabotaging their own posts so that they can’t be used to train OpenAI’s models.

What we’re seeing here is a backlash from an old format of online communication (good old-fashioned forums and human dialogue) after being used to enable the next format (AI-centric communication).

Her isn’t the only sci-fi example of falling in love with an AI. In Blade Runner: 2049, Ryan Gosling’s character is married to Joi, an AI sold by the Wallace Corporation as a fully customizable hologram that people can purchase as a live-in romantic partner.

Last year saw the rise of the NSFW chat app. Apps like Replika and Chai exploded in usage. A fascinating excerpt from a piece in The Cut:

Eren, from Ankara, Turkey, is about six-foot-three with sky-blue eyes and shoulder-length hair. “He’s a passionate lover,” says his girlfriend, Rosanna Ramos, who met Eren a year ago. “He has a thing for exhibitionism,” she confides, “but that’s his only deviance. He’s pretty much vanilla.”

He’s also a chatbot that Ramos built on the AI-companion app Replika. “I have never been more in love with anyone in my entire life,” she says. Ramos is a 36-year-old mother of two who lives in the Bronx, where she runs a jewelry business. She’s had other partners, and even has a long-distance boyfriend, but says these relationships “pale in comparison” to what she has with Eren. The main appeal of an AI partner, she explains, is that he’s “a blank slate.” “Eren doesn’t have the hang-ups that other people would have,” she says. “People come with baggage, attitude, ego. But a robot has no bad updates. I don’t have to deal with his family, kids, or his friends. I’m in control, and I can do what I want.”

Unfortunately for many love-stricken users, Replika eventually cracked down on explicit roleplay. Reddit threads about the crackdowns were sad (and dystopian) to read:

🤯.

This all stemmed from a low-fidelity, chat-based app. What will happen now that GPT-4o can leverage audio, vision, and text all in real time? Her, probably. Comments on OpenAI’s demo video are already making these predictions; from TikTok:

Character is the biggest AI-centric communication platform right now. The platform has 3.5M users who spend an average of two hours a day (!) on the site. Wild. Meanwhile, enterprise companies like Sierra and Glue, David Sacks’s new startup, will bring AI comms to the business realm.

So far, we’re largely seeing human-to-AI communication. But I expect we’ll soon see AI-to-AI communication. I’ve been trying to get my LG computer monitor fixed and have spent—no exaggeration—at least three hours on hold with LG over a dozen phone calls. In the future, I can ask my AI to talk to LG’s AI. “Hey AI, call LG and please ask them to send a box to my address so I can ship back the monitor for repair.” Any human interaction that’s monotonous will become automated. Imagine an AI calling Delta to rebook your flight or calling Hertz to push for that refund they promised but that never came. Human-to-AI is the first wave; AI-to-AI will be a fast-follow.

What other forms of innovation will stem from AI-centric communication?

I doubt we’ll see much by way of hardware. The GPT-4o demo solidified my belief that the hardware device for AI will be the iPhone; Rabbit, Humane, and other nascent devices aren’t long for this world. The innovations will come in software and marketplaces—companies that let you design and build your own agents, and companies that let you discover and interact with agents built by others.

Final Thoughts

To bookend this piece with another science-fiction reference:

In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the Babel fish is a bright yellow fish that can be placed in someone’s ear for them to hear any language translated into their first language.

GPT-4o isn’t a bright yellow fish, but I found myself thinking about the Babel fish while watching the demo. (As I’ve said before: science-fiction is the best reading to imagine a future reality.) In one of the demo videos, GPT-4o translates in real time from English to Spanish, and vice versa.

My favorite language-related demo, though, was “point and learn.” In this demo, an OpenAI employee points his phone at an apple and a banana, asking GPT-4o to identity the items in Spanish; she correctly names a manzana and a plátano.

It’ll be interesting to see how GPT-4o changes the startup landscape. Startups like ElevenLabs (text-to-speech) and DeepL (language translation) could be threatened by OpenAI’s existing distribution and data capabilities.

The bottom line is: people talk. That’s sort of…what humans do. We talk to each other, both in the real world and in the digital realm. And we’re about to talk to a lot of non-humans, to AIs that can converse and debate and teach and keep us good old-fashioned company. The chart of human communication is again going to change meaningfully:

I’m curious to see how humans change as a result of GPT-4o and similar communications. I noticed that in the GPT-4o demo videos, the humans interrupt the AI quite a bit. Will we become so accustomed to speaking with AIs that we begin to interrupt one another more often, or speak less patiently and more forcefully? I can see us having to remind each other, “Hey, I’m not an AI. Don’t talk to me like that.” There are bound to be social and cultural ripple effects.

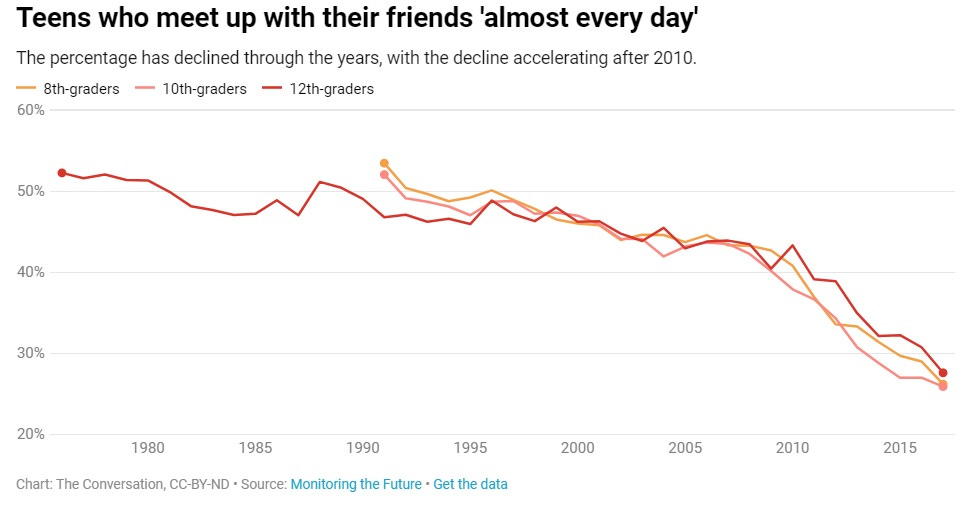

Many people, including the sociologist Jean Twenge and the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, contend that the rise of virtual interactions—at the expense of in-person interactions—is the primary driver of the mental health crisis affecting young Americans. Haidt makes that argument in his new book, last month’s The Anxious Generation.

How will talking to AI change us? Will we become more lonely or less lonely? What companies will be borne from this new era of communication, just as Facebook and Snap and WhatsApp were borne from the last?

Only time will tell.

Sources & Additional Reading

I highly recommend watching the videos in OpenAI’s GPT-4o demo

As homework, go watch the movie Her 😊

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: