Weekly writing about how technology shapes humanity, and vice versa. If you haven’t subscribed, join 40,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

AI’s Interface Revolution

I’ve been meeting more and more young people who consider an AI bot to be among their friends. For some, the AI is a close friend; one 17-year-old I spoke to told me, “I talk to my chatbot more than I talk to most of my friends from school.”

Maybe this shouldn’t come as a surprise, given that the number of close friends we have is on the decline. In the last 30 years, the percentage of people with <=1 close friend has nearly tripled to 20% of the population. The percentage of people who report 10+ close friends has dropped from 40% to 15%.

People are lonely, and AI offers a constant companion. One popular app is Chai—a portmanteau of “Chat” and “AI”—which offers “chat with AI friends” and which has amassed over 1M downloads. If you want to send over 100 messages a day on Chai, you have to pay for Premium, which will cost you $134.99 a year or $13.99 a month.

On the subreddit for Chai, dozens of people share stories of building deep friendships with their AI companion. Predictably, this bleeds over into intimate and sexual relationships. Earlier this year, the app Replika blew up when it allowed NSFW content. In March’s Maslow’s Hierarchy of Startups, I wrote about how people were falling in love with their Replika bots. A fascinating excerpt from a piece in The Cut:

Eren, from Ankara, Turkey, is about six-foot-three with sky-blue eyes and shoulder-length hair. “He’s a passionate lover,” says his girlfriend, Rosanna Ramos, who met Eren a year ago. “He has a thing for exhibitionism,” she confides, “but that’s his only deviance. He’s pretty much vanilla.”

He’s also a chatbot that Ramos built on the AI-companion app Replika. “I have never been more in love with anyone in my entire life,” she says. Ramos is a 36-year-old mother of two who lives in the Bronx, where she runs a jewelry business. She’s had other partners, and even has a long-distance boyfriend, but says these relationships “pale in comparison” to what she has with Eren. The main appeal of an AI partner, she explains, is that he’s “a blank slate.” “Eren doesn’t have the hang-ups that other people would have,” she says. “People come with baggage, attitude, ego. But a robot has no bad updates. I don’t have to deal with his family, kids, or his friends. I’m in control, and I can do what I want.”

Straight out of the movie Her.

Unfortunately for Replika’s users, the startup changed its rules to eliminate erotic roleplay. Overnight, people’s AI boyfriends and girlfriends were gone. Reddit threads about the phenomenon are sad to read:

Another phenomenon is young people turning to chatbots as therapists. Milo Van Slyck, a transgender man in Charleston, got into the habit of talking to ChatGPT daily as his therapist. According to Bloomberg, “[Van Slyck] says he often feels like a burden to other people, even his therapist, but he never feels like he’s imposing on the chatbot.” Chatbot startups like Woebot and Wysa now focus specifically on mental health, and they’re far more affordable than human therapists. Of course, they’re also far more unproven when it comes to bias, privacy, and medical advice.

Also in vogue: using AI to secretly hold down multiple jobs. Says one man, “ChatGPT does 80% of my job.”

Other emergent AI applications are more innocuous: there’s a growing trend of young people using AI to help brainstorm witty pick-up lines and flirtatious texts. Products like Rizz, Keys, and Your Move all serve this purpose. Check out this pun that Rizz outputs from the prompt, “Generate a flirty one-liner for my hinge match, she likes boba”—

The point is: interaction with AI is becoming second nature to us.

This means that how we interface with technology is changing dramatically, and these shifts don’t happen very often; mobile may be the most recent interface revolution on this scale, over a decade ago. When these revolutions happen, they tend to happen fast.

It’s easy to forget now, but Facebook almost missed the mobile revolution. In 2011, Facebook proudly presented its annual F8 developer conference. The only problem? Nearly every product it unveiled was built for the web. While the Facebook team had been hard at work preparing for the conference, the world had been rapidly becoming mobile-first.

Facebook had iPhone and Android apps, but they were pretty terrible: they’d been built on HTML5, a language better for building web pages than for mobile apps. As a result, they were buggy and slow. In 2012, Zuckerberg—recognizing his mistake—pivoted the entire company to mobile. Zuckerberg began to work exclusively from his iPhone, forcing himself to become mobile-first; he even wrote Facebook’s 4,000-word S-1 filing on his phone. Facebook Product Managers disabled the desktop version of Facebook, going all in on mobile. Zuckerberg declared that all meetings would present the mobile version of products first; if they failed to do so, the meeting would be over.

Turning the ship worked, and Facebook stock soared 900% from its May 2012 IPO to its peak in September 2021 (it’s now up about 460% since IPO). Today, roughly 80% of time spent on Facebook happens on mobile; for Instagram, which was always mobile-native, that figure is close to 100%. But Facebook came shockingly close to missing the most important consumer technology revolution in history.

I expect we’ll see a lot more stories like this in the coming years.

The AI revolution is happening—fast. In a few years, it will sound silly to call a company “an AI company” just as it sounds silly today to call a company “a mobile company.” AI will be part of everything.

That said, there will be AI-native companies, just as there were mobile-native companies in the 2010s—examples just from the home screen of my phone: Instagram, Snap, Uber, TikTok, and Robinhood. The massive shift in interfaces creates an opportunity for the startups, the AI-natives, and a vulnerability for the incumbents, the AI-adopters.

Let’s pause for a moment and look at new ways we’ll soon interface with AI.

In The AI State of the Union two weeks ago, we covered ChatGPT plugins. Last week, OpenAI President Greg Brockman delivered an excellent TED Talk that dug into plugins in more detail, including a live demo.

On the TED stage, Brockman announced that he would ask ChatGPT to suggest a meal for him to enjoy after his TED Talk. He would also use the DALL-E plugin to draw him a picture of his meal. (DALL-E is OpenAI’s text-to-image model, a portmanteau of Salvador Dalí and Pixar’s WALL-E—lots of portmanteaus in AI!)

First, ChatGPT came up with a meal that included a quinoa salad, mushroom caps stuffed with goat cheese, and butternut squash soup. Admittedly, it sounded pretty tasty. Then, DALL-E produced an AI-generated image of the meal:

The way this works is ChatGPT actually generates a text prompt behind the scenes—just as a human would—and then feeds that prompt into DALL-E through the plugin.

Satisfied with how the meal looked, Brockman asked ChatGPT to create a shopping list for the ingredients. ChatGPT first uses the Retrieval plugin—a plugin that helps it remember a prompt from the past—and then uses the Instacart plugin to produce the link to an Instacart shopping list.

You can see in the screenshot below that Instacart’s interface still has an important role to play here; a user is ported over to Instacart and can edit their shopping cart. The discovery of Instacart though—the customer journey to visiting Instacart.com or opening the mobile app—is completely different. This is crucial; we’ll circle back to this in a bit.

In his final step, Brockman had ChatGPT tweet out his recipe. ChatGPT uses the Zapier plugin to connect with Twitter and produce a tweet, all in real-time. The entire process—requesting the meal, ordering ingredients, and tweeting it out—all takes less than a few minutes.

Watching this demo, it’s clear that how we interact with businesses is about to change. Brockman never Googled “recipe for dinner,” he never sought out Instacart, and he never logged onto Twitter. He did everything through ChatGPT.

Plugins will soon roll out broadly, and we’re seeing more examples of AI interfaces pop up. Aidan Gomez, the co-founder and CEO of Cohere and author of the seminal Attention Is All You Need paper that proposed transformer architecture, built his own AI agent as a side project. As Eric Newcomer tells it, Gomez gave the agent access to his credit card and his password credentials to “a ton of different websites.” If Gomez says, “Go buy me some soap,” the agent knows his address and can order the soap right to his doorstop. Presumably, Gomez no longer needs to visit Amazon.com.

These examples prompt interesting questions: what does this mean for advertising, for customer acquisition, for brand? What does this mean for distribution?

What does this mean for distribution?

Every startup needs distribution; every startup needs to find customers and hit escape velocity. One of my favorite Paul Graham quotes captures it well:

“A startup is a company designed to grow fast. Being newly founded does not in itself make a company a startup. Nor is it necessary for a startup to work on technology, or take venture funding, or have some sort of ‘exit.’ The only essential thing is growth. Everything else we associate with startups follows from growth.”

But we’re at a uniquely challenging moment for distribution. For starters, every company is facing CAC headwinds. In the post-ATT world, acquisition costs are rising and measurement is deteriorating. At the same time, Big Tech incumbents are bigger and mightier than ever. Existing distribution can crush competition. This chart of Microsoft Teams vs. Slack is alarming:

How will an AI productivity startup compete with Google and Microsoft, which have billions of users across Google Workspace and Office 365? Or, for that matter, how will startups not remain at the whim of OpenAI? AI-powered copywriting startups like Jasper and Copy.ai were among the first applications of AI. They got to impressive scale quickly by building on top of OpenAI’s models, only to be caught flat-footed by OpenAI launching ChatGPT last November.

Startups will have to leverage traditional advantages to win market share and to build defensibility: speed and agility; network effects; vertical focus (for instance, focusing on the legal vertical or the HR vertical); and data moats.

But given how fundamentally distribution is changing, there will also be openings for savvy new companies. I had a good conversation last week with Mike Volpi—my go-to AI guru—as we debated whether this moment will create an Innovator’s Dilemma for incumbents.

We’re used to visiting Airbnb to find a place to stay on vacation. But what happens when we can just tell an AI companion, “Book me a home in Madrid for the week of May 12th.” The AI companion has no brand loyalty; Airbnb’s hard-earned name recognition—the result of millions of marketing dollars and a decade of word-of-mouth—now means nothing. As the user, I only care about finding a decent place to stay for a good price; I don’t care whether that’s through Airbnb, Booking.com, or a new AI-powered upstart.

Airbnb has put a lot of effort into building its brand, and it will be hesitant to disrupt itself and devalue its brand. That could make it vulnerable.

The Innovator’s Dilemma, first theorized by the late Harvard professor Clay Christensen in 1997, proposes that successful businesses tend not to disrupt themselves. Why would they? Their incentives are to please their current customers, not to shift to a new technology that may—in the short-term—rock the boat. The example people are pointing to right now is Google: ChatGPT poses the most serious threat to Google Search since its founding in 1998—yet Google has an extremely lucrative search business ($162B of its $280B in 2022 revenue came from search ads) and will be hesitant to mess with its golden goose.

The Innovator’s Dilemma creates an opening for startups, and in this tech epoch it will create an opportunity for AI-native startups. Amazon is America’s favorite brand, but even the Amazon shopping experience could be threatened. Most Americans visit Amazon.com, search “paper towels,” and buy the product. It’s a relatively frictionless experience, despite Amazon’s dark patterns. But that same transaction could be done in seconds with an AI companion like ChatGPT. “Buy me paper towels, 8-pack, and send them to the house.”

Amazon’s search-driven shopping experience devalued the importance of brand. You didn’t really care which paper towels you bought, as long as they were inexpensive and had good reviews. Bounty holds less importance on Amazon than it does on the grocery store shelf, where it sits at eye-level and where it’s colors and logo are more recognizable. Amazon became the brand, not Bounty.

Interestingly, AI could do something similar to businesses. Does an AI interface devalue the importance of Amazon’s brand? Maybe. Millions of customers will still visit Amazon.com, of course, and disruption will happen slowly. But an AI upstart that’s not afraid to sacrifice some brand value for the customer’s convenience might take market share. What if ChatGPT, which now has over 100M users, adds a Walmart.com plugin? All of a sudden, many of us may getting our paper towels from Walmart instead of from Amazon.

This illustrates the importance of partnerships; I’m sure Amazon is exploring a deal with ChatGPT behind the scenes. Clearly, Instacart’s ChatGPT plugin is important for ensuring that “order me the ingredients” in the example above leads a user to Instacart’s website. Notice that Brockman never requested that ChatGPT use Instacart; he simply said, “Now make me a shopping list.” What if Amazon Fresh had been the preferred partner instead?

The customer discovery journey to products and services will change dramatically, in turn requiring every company to rethink how it gets in front of customers. The old playbooks—paid marketing, brand awareness—will still apply, but they might not hold the same importance if an AI chatbot is the interface through which we interact with businesses. With ChatGPT, OpenAI has unwittingly become a consumer company. We’ll see if Plugins catch on to begin abstracting away other services.

Another important point: in the TED Talk example, Instacart’s interface is still part of the consumer experience with ChatGPT Plugins. That’s good for Instacart. But Instacart doesn’t necessarily need to be part of the experience. That step could easily take place all within the ChatGPT interface—or the interface for any up-and-coming AI companion—which could fully abstract away the third-party providing the service. I wouldn’t be surprised if we see this start to happen.

Consumers tend to prefer things that are fast and convenient. AI interfaces will promise an improved user experience on both fronts. I expect that fewer consumers will be loyal to brands than businesses think they will be. I also expect that brands that require trust will be tougher to disrupt. Airbnb, for instance, has trust around staying in a stranger’s home; knowing your AI chatbot booked through a reputable service will be important. A more commoditized service—where your paper towels come from, for instance—may be more easily disrupted.

There are plenty of examples we could give here. The point is: AI is a radical new paradigm for interacting with businesses. We might not visit websites or open apps nearly as much anymore. Those have been our ports to the web…forever. Or at least since the modern digital age was born.

We haven’t seen this much change in technology interfaces in a long, long time. In an interface revolution, everyone becomes vulnerable, new behaviors emerge, and tremendous value all of a sudden becomes ripe for the taking.

Final Thoughts

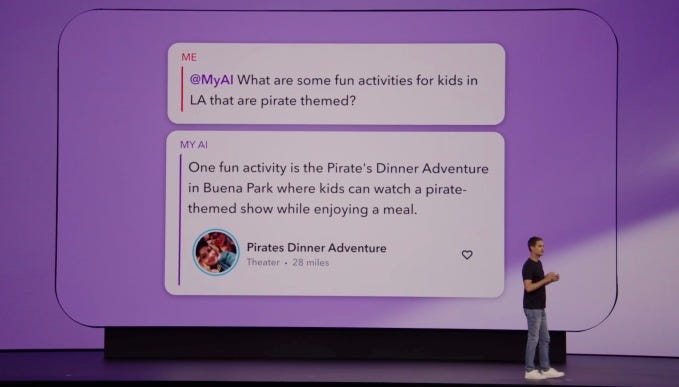

Distribution isn’t always enough. One interesting thing to watch has been Snapchat users’ reactions to Snap’s new “My AI” companion. “My AI” rolled out broadly to Snap’s 750M monthly active users last week (it had been previously been limited to paying subscribers). The product featured heavily in the Snap Partner Summit, and Snap clearly is putting a lot of emphasis on it: My AI appears at the top of every Snap user’s homepage, with everyone automatically opted in.

That hasn’t gone over so well.

The average App Store review for Snapchat in the past week was 1.67 stars, with 75% of reviews being one-star. In Q1, for reference, the average was 3.05 with only 35% one-star reviews. Users clearly want Snap to know the source of their anger: the number of daily reviews is up 5x since last week and “AI” is the top keyword in reviews.

It turns out that users don’t like that My AI was forced on them without their consent. Many are also surprised to learn that My AI knows their location, even if they’re not sharing location with Snap. As TechCrunch observes, “In a way, the AI bot is surfacing the level of personal data collection that social media companies do in the background, and putting it directly in front of the consumer.”

This will continue to be a hot-button issue: a Washington Post project called “Inside the Black Box” lets you enter any internet domain name to answer the question: “Is your website training AI?”

The next few years will bring upheaval around how we discover and interact with businesses. Will you still visit Amazon.com in five years? Will you open the Uber app to call a car? Or will you ask a chatbot, “Get me a ride to the airport for under $30” and have the entire service provider removed from the equation? In the latter scenario, what importance does brand retain, and how does customer acquisition work?

It will be interesting to see how consumers continue to embrace or reject AI, particularly as Plugins roll out more broadly and as more applications and partnerships emerge, powered by companies like Langchain. Some consumers have gone so far as to have an AI best friend, lover, or therapist. Others are angry at the mere proposition of AI being featured in a social network.

Consumer behaviors are evolving in front of our eyes; we haven’t seen this much change in technology’s application layer in a decade. Massive change creates massive opportunity.

Sources & Additional Reading:

Shoutout to Mike Volpi and Bryan Offutt for being thought partners on how interfaces and distribution are changing

Greg Brockman’s TED Talk can be viewed here

AI and dating apps | Taylor Lorenz, WashPost

The Unbearable Heaviness of Being Positioned | Packy McCormick

The Innovator’s Dilemma | Clay Christensen

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: