Beauty Is in the Algorithm of the Beholder

Ozempic, the Snob Effect, and Shifting Societal Beauty Standards

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 65,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Beauty Is in the Algorithm of the Beholder

Last week, I saw an interesting TikTok from user Nina King that made me think: with Ozempic becoming cheaper, King mused, thinness would become more accessible. Would this mean that thinness would no longer be the beauty standard?

King references Bill Bryson’s At Home, a good book that chronicles some interesting parts of human history. Bryson spends a fair amount of time talking about “the snob effect,” which posits that the demand for a specific good by those with a high income is inversely proportional to the demand for that good by those with a lower income.

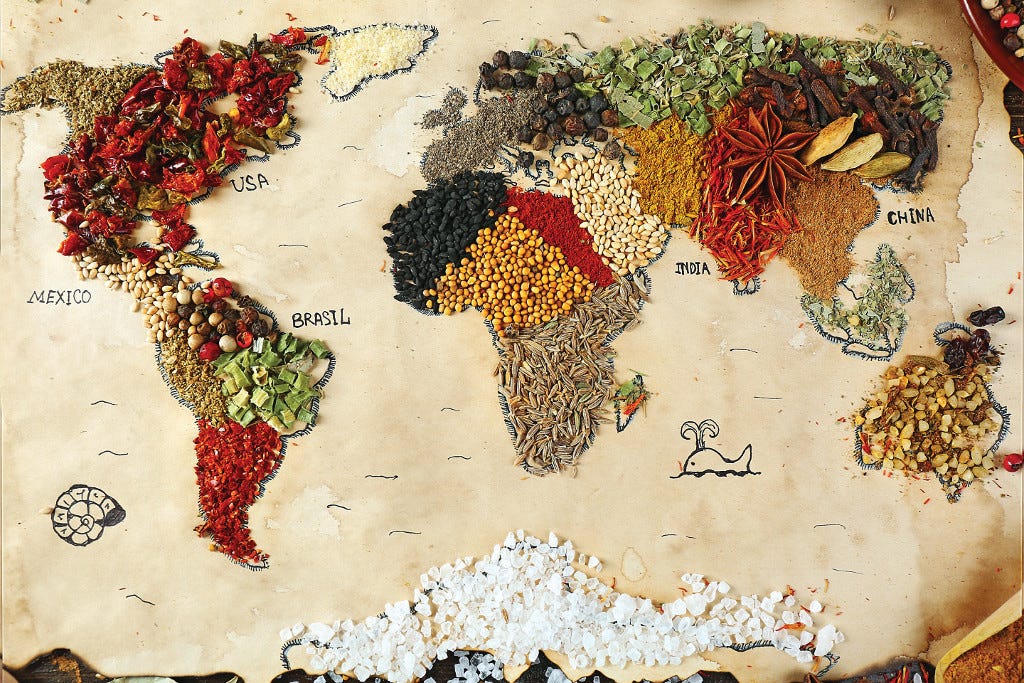

Take the spice trade, which took Europe by storm a few hundred years ago and which Bryson cites as a prime example of the snob effect. From the 15th to 17th centuries, Europeans really wanted spices—so they invaded and colonized a bunch of countries to get them. But as European control of spices grew, the cost of spices went down; soon, even the working class could season their food with spices.

Heavily-spiced foods, which had once been a status symbol, lost their allure—the accessibility of spices neutralized their desirability. (Ever wonder why British food is so bland? With spices so abundant, no one cared anymore.) Many Europeans, like the Brits, instead became obsessed with how hot they could get their food—a new marker of status. Now you know why you burn your tongue every time you have tea in London.

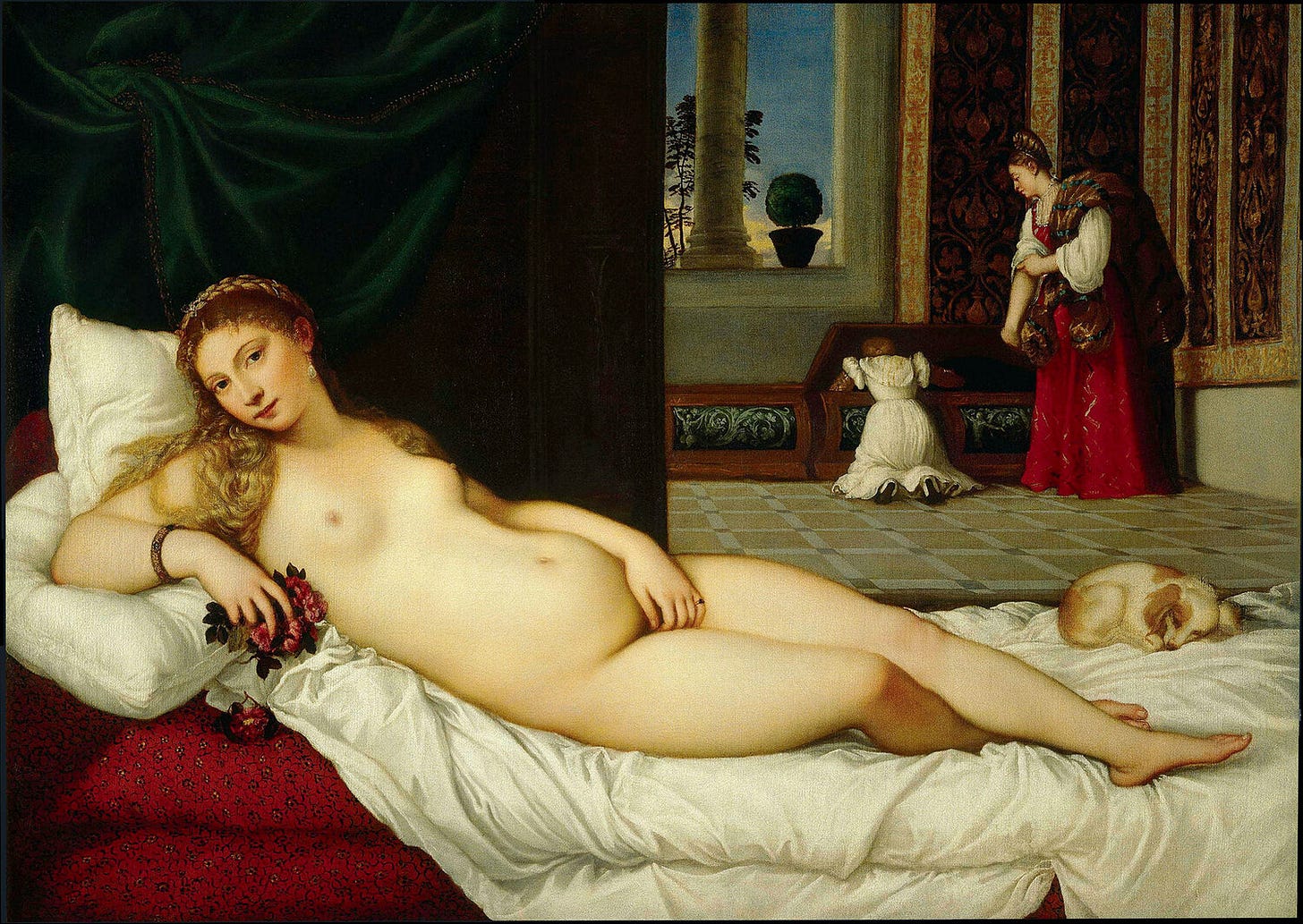

Let’s return to weight. Throughout most of human history, being plump was the beauty standard. Having a bit more weight signaled that you were of higher income, that you could afford food. This standard began to change around the Industrial Revolution. Today, of course, being thin is what’s desirable: the most calorie-dense foods are the cheapest, and having the leisure time to go to the gym and eat well flexes your status.

GLP-1 agonists are still expensive. They’re a rich person’s product. But that’s changing. A March 2024 study found that Ozempic could be manufactured for less than $5 per month, significantly lower than its list price of ~$1,000 per month. The US government, meanwhile, is expected to include Ozempic in a list of drugs that Medicare will negotiate prices for, due to be announced in February 2025. If Medicare covers Ozempic for obesity treatment, commercial insurers should follow suit.

So what happens when everyone can be thin?

Evolving Beauty Standards + “The Selfie Thesis”

It’s interesting to step back and think about shifting beauty standards more broadly.

We’re becoming a more visual culture: the internet turbocharged vanity. 2022’s The Seven Deadly Sins of Consumer Technology looked at how popular internet products often prey on our innate human behaviors, and how plenty prey on Vanity specifically: companies like Instagram, sure, but also companies like Lightricks, the Israeli maker of editing apps like Facetune. (Technically, Envy is one of the Seven Deadly Sins, and Vanity isn’t—but Vanity is a close cousin of Envy.)

I’ve written in the past about “the selfie thesis”—my view that any product or service that makes us look better in a selfie (or on a Zoom meeting) probably has tailwinds behind it.

Let’s tick through a few examples.

Med Spas and Non-Invasive Cosmetic Procedures

First, we’re seeing an explosion in cosmetic procedures. Over the past few weeks, the internet has become obsessed with the “glow-ups” of celebrities like Lindsay Lohan and Christina Aguilera. Hundreds of TikToks have dissected their appearances, declaring, “There’s a new surgeon in Hollywood.”

Celebs like Lindsay and Christina aren’t alone—the med spa market is booming. The industry will swell from $18B last year to $84B+ by 2032—a 19% CAGR.

More and more people are opting for non-invasive procedures; Botox seems completely destigmatized and widespread. Growth in non-invasives is accelerating every year:

How does this trickle into Silicon Valley? Some companies, like Moxie, have grown quickly by building vertical software for brick-and-mortar med spas. Others, like Persimmon, enable at-home Botox and injectables—the model here is clever, allowing nurses to earn supplemental income (most nurses administer Botox as a side hustle during their days off), while allowing customers to avoid stigmas of going in person to get their Botox.

But just as people catch up, are beauty standards again changing? As one TikTok comment observes:

The snob effect is, well, in effect. Many commentators—including TikTok-famous plastic surgeons—think the Lindsay and Christina transformations are the result of 1) dissolved filler, and 2) the so-called “ponytail facelift,” which is all of a sudden the procedure du jour.

Of course, it’s taboo to comment on people’s cosmetic procedures—and on whether someone might be on Ozempic. But for many celebrities—including Aguilera, Oprah, and Kelly Clarkson—there has been rampant online speculation about GLP-1 agonists.

The Ozempic Economy

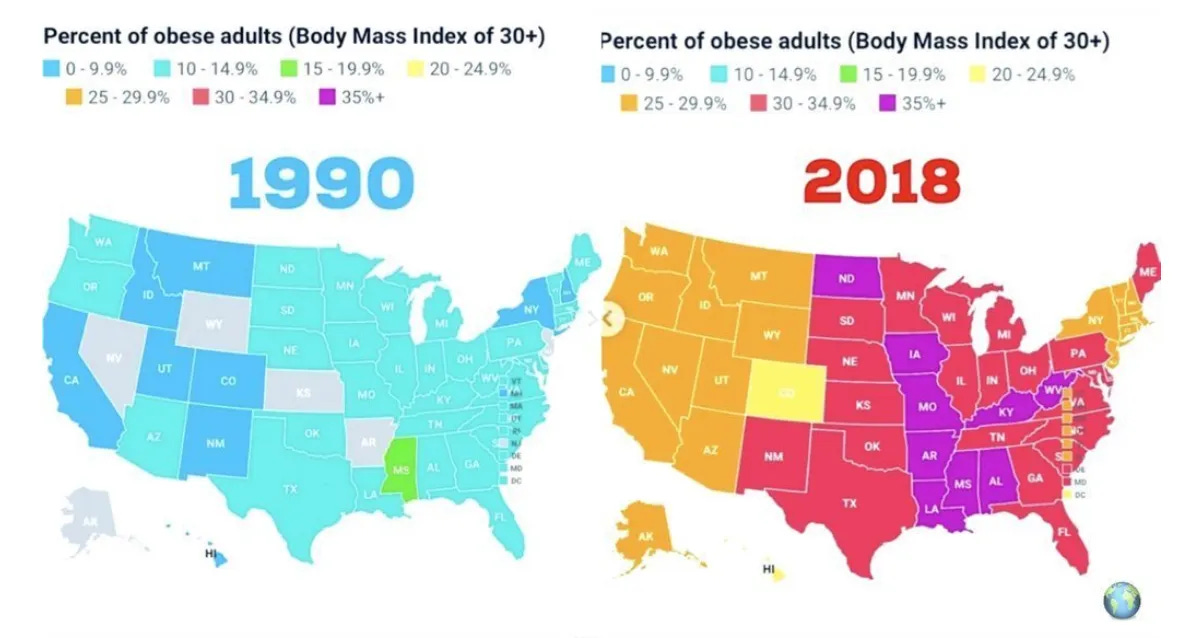

America clearly has an obesity problem. Back in January 2023, in The Startups Combatting Obesity, we shared this chart, which comes from Justin Mares:

In 1990, zero states had obesity rates above 20%. In 2018, zero states had obesity rates below 20%. Yikes. Since 1990, the rate of obesity has doubled among American adults. Nearly 3 in 4 adults in America and more than a third of children are overweight or obese.

Why? Well, to put it bluntly: it’s the food, stupid. Ultra-processed foods—think chips or sugary cereals—now make up 73% (!) of America’s food supply. These foods comprise 60% of the typical adult’s diet and 66% of the typical kid’s diet.

This is a very American problem. Here are US obesity rates compared to Europe:

That January 2023 Digital Native piece goes into more depth, but clearly this problem continues to get worse. This is why I think it’s a when, not an if, that the government and commercial insurers cover GLP-1 agonists. So what’s happening in the Ozempic economy? (Side note: Ozempic is the name of the drug used to treat type 2 diabetes that also has weight loss effects; Wegovy is the name of the drug specifically prescribed for weight management. Ozempic has seemingly become the catch-all term in culture that refers to GLP-1 agonists broadly. Both Ozempic and Wegovy are made by Novo Nordisk.)

This piece is a great read on how Ozempic is shaping Americans (hat tip Damir for the rec), and here’s an interesting chart on how widespread GLP-1s have become across the 50 states:

Pretty quick work for a drug that’s still relatively new (and one that’s still prohibitively expensive). The Economist estimates that by 2031, the market for GLP-1 drugs will be over $150B. For perspective, that’s on par with the market size for all drugs used to treat cancer ($185B in 2021).

So how does this shape the business world? Here are new US business listings for med spas and weight-loss centers:

The med spa boom mentioned earlier certainly rides the GLP-1 tailwinds. But GLP-1s are also powering telehealth. Hims has quietly become a powerhouse in telehealth, expanding far beyond its original focuses (erectile dysfunction, hair loss) and amassing ~$1B in annualized revenue and a $5.5B market cap.

Hims began offering oral weight loss pills like metformin (not a GLP-1) last year, and that line of business now rakes in $100M+ a year. Only recently has the company added Ozempic and Wegovy, alongside a compounded version of semaglutide GLP-1 that is significantly cheaper—about $200/month, 10-20% of branded Ozempic and Wegovy prices. My friend Gaurav wrote a good breakdown of Hims’s foray into weight loss, and he estimates that GLP-1s are still only about ~$16M or less in annualized revenue. But clearly the company is investing heavily into these products, with the hopes of riding one of the biggest waves in modern healthcare: JP Morgan estimates that by 2030, about 10% of Americans will be on GLP-1s.

Amazon has also gotten into the race, largely through One Medical, which it bought for $3.9B in 2022. Amazon operates a pharmacy in New York that offers GLP-1s like Zepto, and it should double down on the category given the size of the prize to be won.

AI Editing

Social media gave rise to so-called “Instagram face”—people getting procedures to look in real life as they do on Instagram. This is a huge trend in plastic surgery. But what happens when AI can take our distortions of reality to the next level?

The aforementioned Facetune, made by Lightricks, popularized photo editing in the mid-2010s. The app ran ads like this:

And prompted memes like this one:

What’s the next evolution?

AI should give us even more control over online appearance. Imagine snapping a photo at the beach, then being able to prompt a model: “Make my hair longer and wavier. Make my skin tanner and add freckles. Make my nose thinner and my cheekbones more pronounced.” Humans are vain creatures; we’ve already established that. I imagine we’ll go as far as technology will allow us to come across more desirable. Deepfakes will be an issue, but so will AI-edited images of people’s bodies and faces.

In his 1996 novel Infinite Jest, David Foster Wallace foretold a version of America that looks eerily like our country today. In Wallace’s novel, the rise of a “video phone” makes users so self-conscious about their appearance that they turn to digital masks to look perfect on screen. These masks airbrush wrinkles, whiten teeth, and erase eye bags. Eventually, people who use the digital masks become so vain and so obsessed with looking flawless that they refuse to interact with people in real life, sans mask.

Written at the inception of the internet (11 years before the first iPhone), Infinite Jest was shrewd in understanding that humans will always use technology to improve appearance. AI will be the next tool, in a long lineage of tools, designed to accomplish that familiar goal.

Skincare, Dermatology, and Beauty

The above examples make our focus on aesthetics sound bad. We can’t help it; it’s human nature. And while some extreme procedures or unhealthy beauty standards can be bad, much of our focus on aesthetics also means a focus on health. GLP-1s are an amazing drug; sure, they’re stigmatized, but hopefully they can help reverse our obesity epidemic. The “acceptance” of obesity in culture over the past few years—an offshoot of woke mania—isn’t a good thing: obesity is a serious health epidemic, and we need to innovate our way out of it (if we can’t solve it by changing the food supply or with good policy, which it seems like we can’t!).

Take skincare, one of the fastest-growing sectors out there:

Gen Z loves skincare. And while some skincare centers on vanity, yes, much actually centers on broader health. I’ve written in the past about Honeydew, one of our Daybreak companies that breaks down barriers to dermatology care. Over 100M Americans have a chronic skin condition, 2x the number who have diabetes. But nine out of 10 people with a treatable skin disease don’t get treatment. Honeydew is an example of a company that broadens access to care, allowing people to get treatment for intense issues like cystic acne, eczema, or psoriasis.

We see companies like Nourish, Fay, and Berry Street do something similar for dietitians—they make your consults with a dietitian covered by your insurance, thereby expanding the market via telehealth. Good healthcare companies can broaden access to care. Yes, health is inextricably tied to vanity—but it also matters for a host of other reasons.

Final Thoughts

Where do we go from here? Well, for one, I expect GLP-1s to soon be covered widely—in a few years, more than 1 in 10 Americans will be on one. This will have ripple effects:

A 5% reduction in weight can cut an obese person’s medical costs by $2,000 per year. A full transition from obesity to healthy weight saves nearly $30,000 in annual medical costs. Will medical costs go down dramatically?

Depression rates among obese children are double those of average-weight kids. Do GLP-1s lead to better mental health?

A new study found that GLP-1s actually worsen mental health. Are the drugs having side effects? No, the study found that for obese people, eating is a huge source of joy. Removing that source of joy deteriorates mental health. So which is it: will GLP-1s improve or worsen our mental health crisis? Time will tell.

Snack food companies are already bracing for a hit, and Walmart is reorienting its SKUs across product categories to reflect use of GLP-1 agonists. Check out the chart below, which shows which snack categories Ozempic users are buying less of (hint: if you’re a maker of meat snacks or trail mix, I’ve got bad news).

One wild effect: it’s estimated that United Airlines would save $80M a year in fuel costs if its customers lost an average of 10 pounds. So do airlines get better margins because of GLP-1s?

These are just some of the ripple effects we’ll see. How else should founders and investors think about what’s happening in health and beauty?

Beyond GLP-1 mania, I expect skincare and beauty to continue compounding rapidly and for med spas to continue booming. I think Botox and other injectables are here to stay, and that we’ll see increased spend on more invasive procedures. That ponytail facelift everyone’s talking about? In five or 10 years, it might be commonplace.

And how will beauty standards evolve with these new innovations and technologies? There’s a good question for your Thanksgiving dinner. Spice up the conversation and debate “the snob effect” over turkey and mashed potatoes.

Some TikTok users think that with Ozempic widespread, muscled bodies will be in. You can’t fake hours in the gym or a pricey personal trainer.

And of course, the rich will stay a few years ahead of the curve. One out-there piece of news to end on: the WSJ reported this week that there’s a new procedure in cosmetic surgery—changing the color of your eyes.

Doctors who perform the procedure use a laser to cut into patients’ corneas, then widen those incisions and fill them with dye. Some people want normal-looking, but different eyes—say, turn brown eyes blue. Other people want intentionally unnatural-looking eyes. It’s only a matter of time until a Star Wars superfan comes out of the hospital with Darth Maul’s eyes.

The procedure is—shocker!—controversial, and only a few doctors will perform it. But more will perform it over time, as the operation costs a hefty $12,000. Where there’s demand, there will be supply.

One day, everyone might have dyed eyes—then the pendulum will swing back, and natural eyes will be back in. The rich will be on to something new to collect status. The cycle will continue.

Sources & Additional Reading

My friend Damir recommended this piece, which is a deep-dive into the Ozempic economy and its ripple effects in culture

My friend Gaurav mused on Hims’s foray into GLP-1s here

Make sure to check out Nina King’s TikTok and Bill Bryson’s At Home

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: