Black Mirror, Euphoria, and Technology's Double-Edged Sword

Examining the Social Impact of Tech

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Hey everyone 👋 ,

Last week’s piece was more practical, diving into the specific companies powering new segments of commerce. Part II of that piece will be in the same vein.

But in between, I wanted to write something different. This week’s piece is more philosophical, tackling existential questions around technology and its impact. I’ll do so through the context of two of my favorite shows. Then next week will be back to tactical and specific 😊

Let’s dive in.

Black Mirror, Euphoria, and Technology's Double-Edged Sword

[Note: Some spoilers for Black Mirror episodes below.]

Black Mirror’s “Hang the DJ” episode opens on Frank and Amy, a couple on a seemingly-mundane first date. But what’s unique about Frank and Amy is that they were set up by a device called “Coach” that matches them with a partner for a set period of time. Frank and Amy are given 12 hours together, enough for “Coach” to determine their compatibility.

It appears that “Coach” concludes Frank and Amy aren’t meant to be: after the 12 hours are up, they’re instructed to go their separate ways. Coach tells them that “The System” will monitor each relationship they’re given, eventually assigning them a lifelong partner on “Pairing Day” with a success rate of 99.8%. Coach pairs Frank and Amy with new matches, but both can’t stop thinking about the other.

Eventually, Frank and Amy decide to run away together. But as they attempt to scale the walls to escape, it’s revealed that none of this is real—it’s all a simulation being run by an algorithm inside a Tinder-like app, assessing how compatible Frank and Amy are in the real world. We see that in 1,000 simulations, the couple ran away together 998 times, thus making them a 99.8% match.

The episode ends on real-life Frank and Amy, each looking at a dating app screen that says the other is a 99.8% match. They lock eyes in a bar and begin their real first date.

“Hang the DJ” is Black Mirror’s commentary on Tinder/Bumble/Hinge and our tech-controlled dating lives—how we live in a totalitarian regime ruled by algorithms.

Black Mirror’s name refers to a blank screen—the moment when your Netflix episode finishes, the screen goes black, and you find your face reflected back at you. In the words of the show’s creator, Charlie Brooker: “Any TV, any LCD, any iPhone, any iPad—something like that—if you just stare at it, it looks like a black mirror, and there’s something cold and horrifying about that, and it was such a fitting title for the show.”

I think of technology as also a two-way mirror: technology reflects and distorts society, and society in turn reflects and distorts technology. Internet culture used to be a subset of culture; now internet culture is culture writ large.

Like most things, this has both good and bad elements. Technology itself isn’t moral or immoral; it’s amoral, and it’s up to us to wield it responsibly. Black Mirror’s commentary on dating apps is chilling, and yet millions (billions?) of people have met their life partner through a dating app. Tinder’s algorithm led me to the person with whom I’ve built a life for the past 6 years—what could be more impactful than that?

The writer Kevin Kelly describes two classes of problems caused by new technology:

Class 1 problems are due to technology not working perfectly.

Class 2 problems are due to technology working perfectly.

Class 2 problems are easier to neatly categorize: they’re the technologies built with mal-intent. But Class 1 problems are both murkier and more common. Algorithms, for instance, can be powerful tools for good. Dating apps are one example, but we see small examples in our everyday lives: every Monday morning, I look forward to my “Discover Weekly” playlist on Spotify, a set of songs masterfully curated for me by Spotify’s algorithms. Yet algorithms can easily slip into Class 1 problems—for instance, when they learn to isolate us in social media echo chambers or to reward clickbaity fake news headlines (you could argue some of this may be Class 2, if business models intended this algorithmic behavior).

The good-bad duality of algorithms and AI is a recurring theme in Black Mirror.

One of Black Mirror’s most moving episodes is “Be Right Back”, which tells the story of a young woman whose husband dies in a car crash. In her grief, she signs up for a service that creates a digital version of her dead husband by digesting all of his past online communications and social media profiles. She’s able to message with him, with the AI predicting his likely responses and humor:

Predictably, this goes south: the widow becomes addicted to this AI replica of her late husband and fails to move on in her life. But there are also potential silver linings: she allows her young daughter to talk with the AI sporadically, as a way to get to know the dad she’ll grow up without.

A more sinister use of artificial intelligence comes in the episode “White Christmas” through a technology called a Cookie. A Cookie is essentially a more futuristic version of a smart home assistant. But the catch is that a Cookie is a small-scale simulation of a real person’s consciousness, trapped inside a white egg-shaped device.

The Cookie sits on your kitchen counter and obeys your commands (“Turn on the lights”, “Play music”), just as Siri or Alexa do today. But the AI is miserable because it’s a person’s fully-intelligent consciousness imprisoned in a computer. (In a cruel twist, the device is designed so that seconds in the real world pass by as years in the device—this ensures that the person’s consciousness has its will broken and thus acquiesces to commands.) This episode invites fascinating ethical questions: for one, is this a form of torture? The AI isn’t real, of course, but it thinks it is.

A more optimistic take on a similar technology comes in Black Mirror’s best episode, “San Junipero.” In this episode’s world, people who are dying can upload their consciousness to a virtual reality world called San Junipero (filmed in Cape Town), where they live forever in youthful bodies. The story centers on two young women who fall in love in San Junipero as their 90-year-old bodies expire in a nursing home back in the “real world.” The episode is beautiful, representing Black Mirror’s rare optimistic take on the potential of technology.

In the real world, algorithms and artificial intelligence are becoming more powerful and more widespread. TikTok’s algorithm, for instance, often seems to know us better than we do. From Michelle Santiago Cortés’s recent piece in The Cut:

Emely Betancourt would rather show you her Notes app before handing over access to her TikTok For You Page. It’s too eerily accurate a virtual mirror, she tells me, one that took hours of scrolling to create. The For You Page is TikTok’s primary feed. At first, it shows you its most palatable offerings: videos with millions of likes, celebrities, Charli D’Amelio—milquetoast, likable content. As you start watching and liking posts, you go deeper into a niche you’ve co-created with the platform’s famous algorithm. Betancourt knows it sounds intense, but she feels like her FYP truly understands her inside and out: “I feel like it’s really a reflection of my subconscious thoughts; even things I never say out loud, it will know.”

Some people have even learned their sexual orientation from the videos TikTok learns to serve them:

At a recent work dinner, my colleague prompted the group with an interesting question: what’s on your YouTube/TikTok home screen? As we went around the table, people’s answers offered an intimate portrait into their interests and desires and personalities; there are few better ways to capture who we are than what sophisticated algorithms tell us about ourselves.

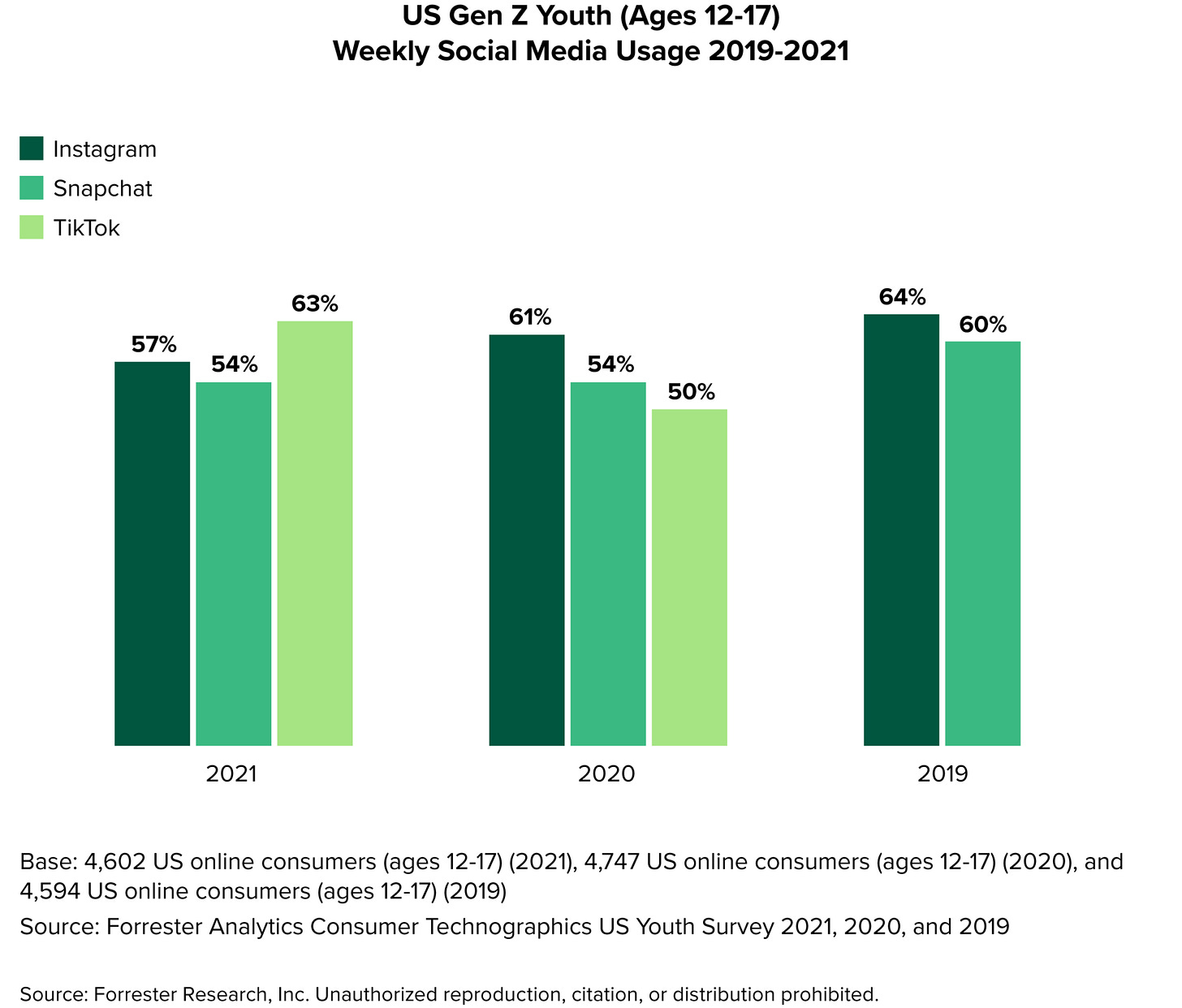

Over a billion users experience TikTok’s algorithm each month. Among U.S. teens, TikTok has skyrocketed to become the most popular social app:

But like all social media, TikTok has a dark side.

The New York Times had a chilling recent piece about Ava Majury, a 14-year-old with 1.2 million followers on TikTok. The article tells the story of how a man named Eric Justin became obsessed with Ava through her TikTok. After Ava began to notice Justin’s comments on her videos, she learned that her “friends” at school were selling the man photos of her as well as her personal information, including her cell phone number and home address.

On the morning of July 10th, Eric Justin showed up at Ava’s Florida house with a shotgun and blew down her front door. As the family cowered in the back of the house, Justin’s shotgun jammed and Ava’s dad, a retired police officer, shot and killed him with a handgun. Investigating officers found that Justin was carrying two cell phones containing thousands of photographs of Ava and hundreds of hours of her videos.

What’s stunning is how little this incident changed Ava or her family’s behavior. Ava continues to post on TikTok daily, though she’s now homeschooled. It turns out that before the incident, Ava, just 14-years-old, had sold Justin photos of herself—with her parents permission. (She sold him two selfies for $300 over Venmo.)

The article ends with Ava waxing poetic about TikTok: “I’d post a video at night, close my eyes, and in the morning it was exciting to see how many views I got.” Her father then chimes in: “It’s like Christmas every day.”

Most commenters seemed to agree on how disturbing the article was:

Ava’s story speaks to how much of an inevitability social media has become to many, and especially to young people—even real-world violence and death can’t cause a young girl to stop posting online. People become addicted to online fame and validation; it fuses into our identities.

This story reminded me of Black Mirror’s episode attacking social media, “Nosedive.” Nosedive takes place in a world in which social media opinion has become the currency used to establish status in society. People are rated on every interaction, given a score out of 5. Your rating determines your quality of life.

The episode follows Lacie, a 4.2 who is desperately trying to claw her way to a 4.5 so that she can qualify for a fancy apartment. Of course, a series of unfortunate events causes Lacie’s rating to plummet, giving us the titular nosedive.

While “Nosedive” is extreme, it mirrors much of our real world. Status is conferred through likes and followers; influencers are adored; people are “cancelled” online.

Other episodes offer additional commentary on social media—in one, for instance, a new device lets you “block” someone in the analog world much as you can block them on Facebook or Instagram or Twitter. The blocked person appears only as a fuzzy silhouette in your vision. In our impending AR world, this technology seems less far-fetched.

While Black Mirror centers its stories around technologies, Euphoria is remarkable in how unremarkably it treats technology. The high school students in Euphoria are digital natives: they don’t know a world without the internet and social media. Their lives casually revolve around technology. The show doesn’t treat this as good, bad, or even noteworthy; it just is.

In this shot, we see a character’s phone reflected in her eye as she cries.

(I’m convinced that Euphoria is the most beautifully-shot show on television. Check out this video as proof.)

This emphasizes an important point: technologies are rarely as revolutionary in the moment as they seem in Black Mirror. Rather, they seep into our lives slowly at first, and before we know it, they’re as inextricably woven into our social fabric as they are in Euphoria. When cell phones first came out, they were viewed as toys for the rich. In 1983, a cell phone cost $4,000—$10,000 in today’s dollars. A cell phone weighed two pounds, was a foot long, took 10 hours to charge, and delivered only 30 minutes of talk time. Fast forward to today, and phones are our banks and schools and health clinics—our portals to society and the connective tissues in our relationships.

Innovation has never happened at such a rapid pace. To use one of my favorite WaitButWhy graphics:

Every day, new technologies are being announced that seem straight of a sci-fi novel—or a Black Mirror episode. Often, we recoil when we learn of them. But over time, they become normalized and a part of everyday life.

Is tech a good thing? Yes. Is it a bad thing? Also yes. It’s both, and the best companies and entrepreneurs will play pivotal roles in shaping how it’s used.

Sources & Additional Reading

Black Mirror, created by Charlie Brooker, is one of my favorite shows. It’s an anthology show so each one-hour episode is a completely independent story. (One of my strong opinions is that there should be more of these, for when you don’t want to commit to a new show or a two-hour movie). Check it out on Netflix. Euphoria is on HBO and is also excellent.

The Anti-Amibition Age | Noreen Malone, NYTimes

Why Do People Resist New Technologies? | World Economic Forum

Because Your Algorithm Says So | Michelle Santiago Cortés, The Cut