Building the Sustainable Economy 🌱

Sustainability Is a Cultural Reckoning That Cuts Across Sectors

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Building the Sustainable Economy 🌱

Last week, Stanford announced the largest gift in university history: a $1.1 billion commitment from John and Ann Doerr to establish the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. The Doerr School of Sustainability will be Stanford’s first new school in 70 years, bringing Stanford’s total to eight schools. (The existing seven are: Business; Earth, Energy, & Environmental Sciences; Education; Engineering; Humanities & Sciences; Law; and Medicine.)

I found it interesting that the School of Sustainability will be distinct from the School of Earth, Energy, & Environmental Sciences. And I think that’s appropriate. The two are related, of course, but the latter is a more clear-cut discipline rooted in the sciences. Sustainability, meanwhile, is something broader: sustainability isn’t a vertical, but a horizontal shift that will affect every industry.

Let’s back up for a minute. In the startup world, “clean tech” has become something of a bad word over the past decade—interestingly, largely because of John Doerr’s own misfortune. Doerr, then chairman of Kleiner Perkins, leaned heavily into clean tech investments starting around 2007. (He reportedly became interested in climate after watching Al Gore’s 2006 film An Inconvenient Truth.) At its peak, Kleiner invested nearly $1 billion into clean tech deals in 2011.

But most of those investments didn’t pan out, and—watching all this unfold—the broader tech world pulled back from clean tech. One of my favorite sayings in startups is, “Being early and being wrong often feel the same.” Doerr wasn’t wrong; he was just early. He was right that climate technology would be a once-in-a-generation shift. Unfortunately, he happened to be 10 years ahead of the game, and that prematureness lost a lot of money for KPCB. It says something about Doerr and his level of conviction that after being burned badly by clean tech, he’s still among the most vocal champions for the space.

In 2022, sustainability is finally poised to have its moment—and it’s going to be a long moment. Powered by 1) worsening climate change, 2) growing regulatory pressure, and 3) massive generational behavior changes, sustainability is positioned to be the defining trend of the next 50 years. No industry will go untouched. VC funding into startups focused on sustainability will return to record levels and, this time, will remain at those levels for 10, 20, 30 years.

When most people think of investing in climate right now, they think of carbon management. Businesses are facing pressure to reduce their carbon footprints from all sides—from regulators, from employees, and from customers. Within a few years, I expect all businesses will be required to report and reduce their footprints.

In The Glass-Half-Full View of Technology, I wrote that I tend to think of the carbon management space in two broad buckets:

First comes carbon accounting. This is how an organization gets a sense of its carbon footprint, involving reporting and measurement.

The question to answer here is: What is my carbon footprint?

Next comes carbon markets. This is how an organization—now armed with data around its carbon footprint—manages and reduces that footprint.

The question to answer here is: What can I do about my footprint?

To make this more tangible, let’s take three companies building along the “lifecycle” of carbon management: Watershed, Patch, and Sylvera.

Watershed helps companies like Airbnb, Shopify, and Sweetgreen measure and report their carbon footprints. With Watershed, companies can answer the question, “What is my carbon footprint?” You can imagine how complicated this question is for global businesses with dozens of business lines and thousands of workers. Sweetgreen, for instance, has to understand the carbon impact of the people who farm its ingredients, the truckers who haul those ingredients to its 550 restaurants, and the operations underpinning those locations. Sounds…challenging.

Once companies are armed with the knowledge of their carbon footprint, they need to offset that footprint. Some do this out of the goodness of their own hearts, but most are facing increasing regulatory pressures to do so (as well as pressures from employees and customers). Patch is a marketplace that connects companies to carbon offset projects—reforestation, wind energy, kelp farming, and so on. Companies like Farfetch, Afterpay, and Sonder can use Patch to link up with offset projects.

Sylvera comes last in this timeline. You can think of Sylvera as Fitch or Moody’s for carbon offset projects. Just as Fitch and Moody’s rate the creditworthiness of a company, Sylvera rates the quality of a project. If you’re a multi-billion-dollar corporation, you want to make sure the massive amounts of offsets you’re buying are legit; you can use Sylvera’s carbon intelligence platform to do so. Companies like Bain & Company, Delta Airlines, and Cargill use Sylvera.

Of course, the lines aren’t so cleanly cut. Watershed, for instance, started in the “carbon accounting” bucket but now also offers solutions for taking action on those emissions. The above descriptions are oversimplified, but the goal is to demonstrate how startups are building technology solutions for corporations that find themselves scrambling to understand and offset their carbon footprints.

A related area that’s seeing a lot of innovation is the supply chain. Leaf Logistics is a company that unlocks more efficient truck freight for companies like Unilever. Kargo offers loading-dock-management technology that reduces trucker dwell time (when truckers hang out and wait to be loaded or unloaded), which is a huge producer of unproductive emissions.

And Remora has one of the most innovative approaches in trucking. Remora created a device that bolts onto any semi-truck, then captures 80% of that truck’s carbon emissions directly from its tailpipe. Remora then sells that CO2 to end users, who store it away.

Many people in the tech world get solace from today’s torrid pace of innovation—they think that we’ll innovate our way out of the climate crisis. And they might be right. There are fascinating companies being started. Heirloom, for instance, aims to remove 1 billion tons of CO2 by 2035, using what it calls “the world’s most cost-effective Direct Air Capture solution.”

I’m somewhere in between—we probably should be freaking out right now, but I also get some solace from the caliber of entrepreneurs working on the climate crisis. Climate tech has been around for a long time—as evidenced by the chart of Kleiner investments above—but we do seem to be at an inflection: technology has come a long way since 2010, and even more importantly (and more depressingly), climate change has advanced rapidly, increasing regulatory scrutiny. Regulatory scrutiny pressures capitalism, which in turn jumpstarts more business creation.

I also get solace from another change, something quite profound: sustainability has become a cultural movement, and arguably the core value of an entire generation. Greta Thunberg is a household name. Middle schoolers self-organize climate walkouts. A 2021 Pew Research report found that 76% of Gen Zs list climate change as among their biggest societal concerns, with 37% listing it as their #1 concern.

There are even mainstream songs being made about climate change. Take Feels Like Summer by Childish Gambino, a.k.a. Donald Glover:

Every day gets hotter than the one before

Running out of water, it’s about to go down

Air that kill the bees that we depend upon

Birds were made for singing, wakin’ up to no sound

No sound

I know you know my pain

I’m hopin’ that this world will change

But it just seems the same

There’s a cultural reckoning happening, and we can see it in consumer behavior. In a McKinsey report last week, nearly half of consumers indicated the environment is a “very important” factor in consumer purchase decisions. (Interestingly, Millennials led the way, ahead of Gen Z. Boomers were a distant last place.)

Consumers—and, consequently, brands—are beginning to walk the walk. When writing about our recent Series A investment in Beam (Investing in Beam: Gen Z, Social Impact, and Commerce), I shared this image:

This checkout flow gives the consumer the opportunity to donate 1% of her cart size to fund the protection of 300 acres of forest for carbon sequestration. Importantly, the consumer pays nothing; the brand is giving up that revenue in order to demonstrate its values (with clear ROI on conversion to boot). A meaningful portion of Beam non-profits are focused on sustainability.

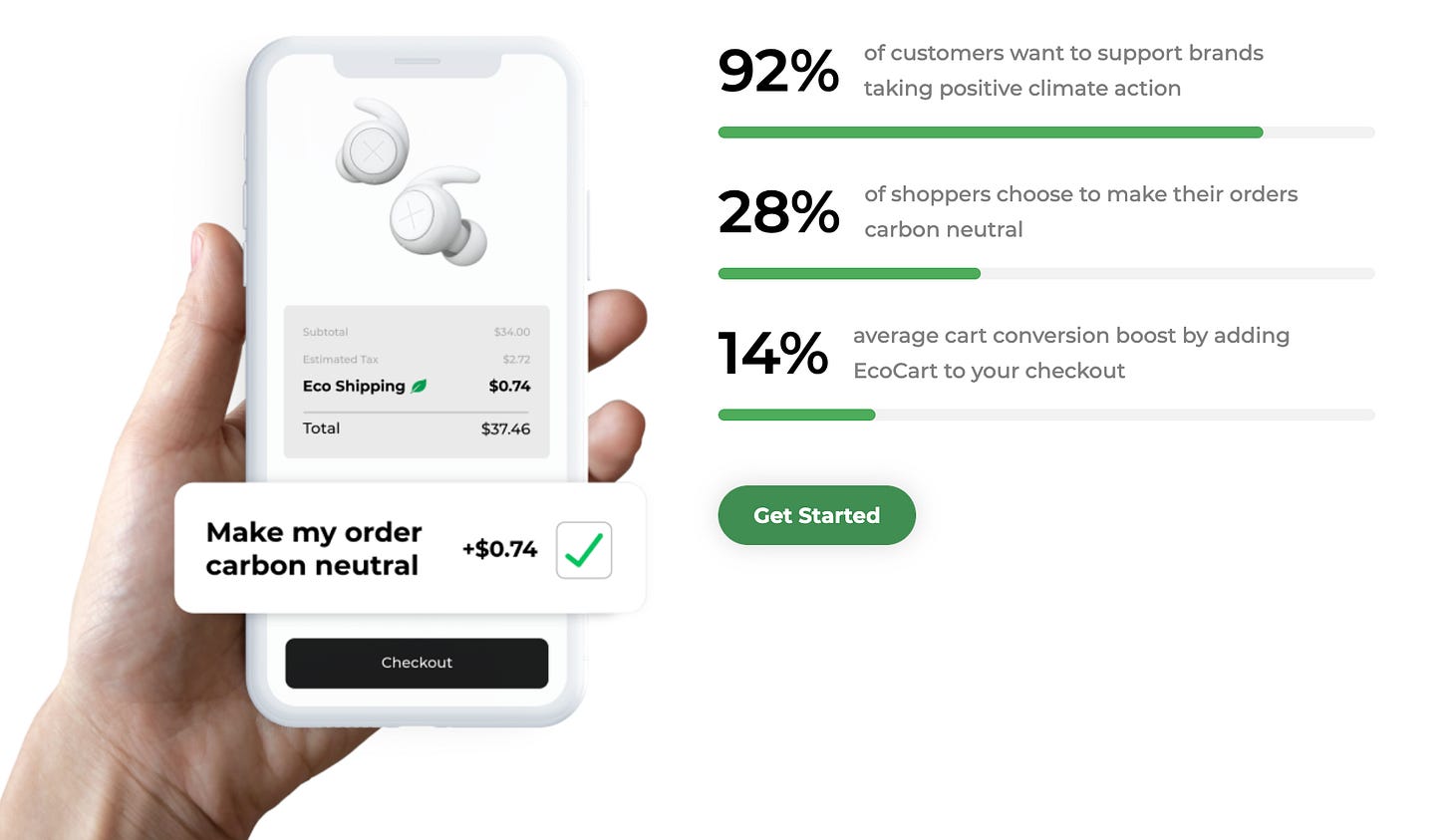

There are also startups specifically built to offset carbon footprints in the purchase flow. EcoCart and Neutrl, for instance, allow shoppers to make their orders carbon neutral. Importantly, here it is the shopper paying—usually an extra 1-2% of total cart value. This might become second nature to young shoppers, though others might balk at having to shoulder the cost. Here’s the flow on Neutrl:

One of the ironies of Gen Z’s passion for climate advocacy is Gen Z’s simultaneous love for fast fashion. Namely, the rise of SHEIN sits in stark contrast to professed values. But consumers will always value convenience and affordability above all. An offshoot of fast fashion’s popularity is that overstock and secondhand are major categories for sustainable commerce.

Globally, 12% of clothing remains unsold at the end of every season—$180B worth of waste. Most of those clothes end up in landfills.

Otrium, one of our investments at Index, is a marketplace that buys excess inventory from brands and then turns around and sells those items to consumers. It’s a clever business model that’s a win-win for both brands and shoppers. (Read my partner Sofia’s excellent piece on Otrium here.)

An adjacent category is resale, and resale remains one of the most underrated markets. Resale is a $40B market expected to double to ~$80B by 2025 and to triple to ~$120B by 2030. About a quarter of the secondhand market is apparel, which will grow 40% per year through 2025. In 2019, secondhand apparel grew 21x faster than traditional apparel and in 2020, 36 million Americans sold items secondhand for the first time. By 2030, the secondhand fashion industry will be nearly twice the size of the fast fashion industry.

Part of secondhand’s growth is driven by a new generation of more environmentally-conscious consumers. We can justify buying SHEIN items today when we can turn around and sell them on Depop tomorrow.

We’ve seen consumer-facing platforms like thredUP, Poshmark, and The RealReal go public. We’re seeing white-label solutions like Archive and Reflaunt power resale for brands. And we’re even beginning to see resale embed itself in the checkout flow—Airrobe, for instance, lets you immediately list your purchases for resale as you buy them. (This, of course, improves conversion—we’re more likely to buy something when we know we can turn around and sell it later for a decent price!)

Sustainable commerce will be one of the major trends of the coming decades, powering megatrends like overstock and secondhand.

Final Thoughts

Sustainability defies categorization. Just as every company has become a fintech (every company needs to offer some form of financing, payments, etc.), every company will become a sustainability company. It’s unavoidable. The biggest trends are often horizontal through-lines like this, cutting across sectors.

Sustainability includes the hard science that we associate with clean tech—the Heirlooms and Remoras of the world—but it also includes the ripple effects of consumer behavior across other industries: fast fashion, overstock, secondhand. Sustainability is a cultural reckoning, and we’re only at the beginning.

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: