CAC: Customer Acquisition Chaos

The Challenges & Opportunities in Connecting Brands and Customers

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

CAC: Customer Acquisition Chaos

The history of commerce is effectively the history of human society. Commerce has existed as long as humans have been around. At its simplest, commerce is defined as the exchange of goods and services for some form of currency. One of the earliest recorded forms of commerce was cattle trade, around 10,000 B.C. Cattle had a fixed value and were exchanged for goods and services 🐮 The Latin word for money, pecunia, comes from pecus, which is the Latin word for cattle.

We’ve come a long way from trading cows. Commerce is now a $26 trillion global market (e-commerce is about $10 trillion), mostly underpinned by cash, credit cards, debit cards, and, increasingly, digital payments. A marketplace is arguably the oldest business model in the world, and marketplaces have been reinvented in the internet age.

Particularly, the internet has reinvented the discovery aspect of commerce—how brands find customers and vice versa. And two decades into the internet age, customer acquisition is at a unique inflection point. That’s the focus of this week’s piece. I’ll frame things by looking at the Past, Present, and Future of customer acquisition.

At the end, I’ll make my first ask of this Digital Native community. TL;DR: if you’re a brand struggling with customer acquisition costs, we have a portfolio company building a new way for brands to acquire customers economically and measurably. Shoot me an email at rex.woodbury@indexventures.com if you want to be connected to the company 📬 More info below.

Now, on to the Past, Present, and Future of commerce… 🛍

PAST

First, some context setting.

There are two primary types of shopping: search-driven shopping and discovery-driven shopping. Today, Amazon dominates search-driven shopping: 74% of online shopping searches in the U.S. now originate on Amazon.com (much to Google’s chagrin). You go to Amazon and you search “paper towels” or “hand soap” or “laundry detergent.” Search-driven commerce often erodes the influence of brand. If you’re Bounty or Ivory or Tide, you need a customer to type “Bounty paper towels” or “Ivory hand soap” or “Tide detergent” to get top billing in the search results. Ben Thompson wrote about this challenge two years ago in The Anti-Amazon Alliance: before the internet came along, Procter & Gamble only needed to market Tide so that a customer would recognize the orange packaging on the grocery shelf.

But now, P&G needs to get that consumer to type the word “Tide” itself—otherwise, top hits for detergent might be for competitors or for Amazon private-label products. Brand recall, as opposed to brand awareness, is a much more difficult and expensive proposition.

Although Tide dominates the U.S. laundry detergent market (41% market share, more than the next five brands combined), when I search “laundry detergent” on Amazon I don’t see Tide anywhere:

Tide ranks 9th, despite having both more reviews and better reviews than any of the Arm & Hammer products listed first. Half of the first eight products I see are effectively advertisements for Amazon Fresh.

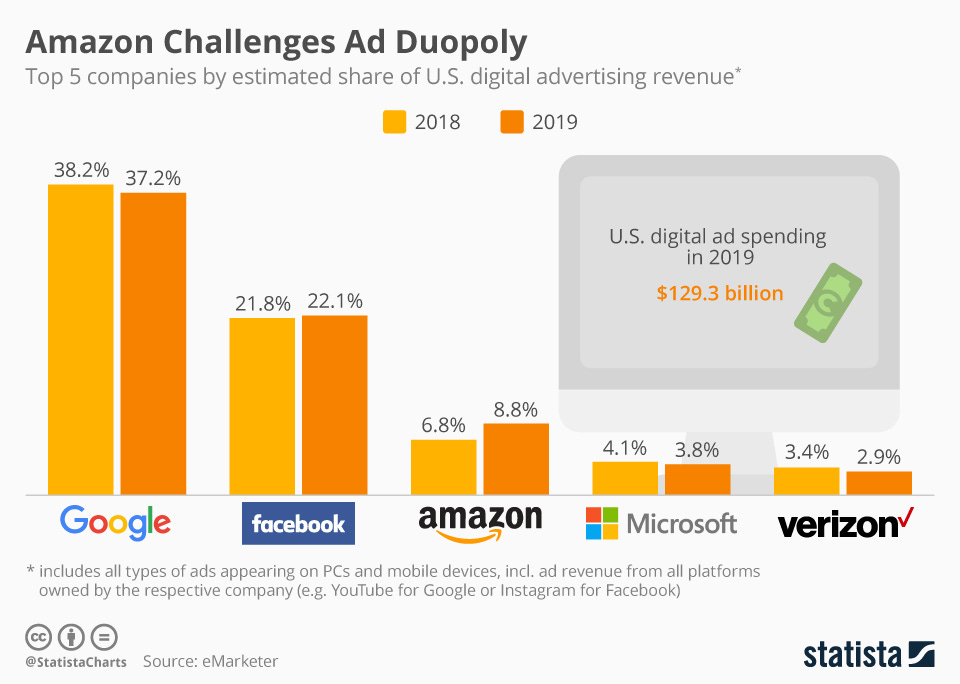

Amazon’s dominance in search-driven shopping is a key reason it’s been able to build a formidable advertising business in a few short years. For the better part of a decade, the Google and Facebook duopoly dominated digital advertising—over two-thirds of every $1 spent on online advertising went to the pair.

That graphic is from 2017, and Amazon didn’t even register. It was around that time that Amazon began turning on its advertising engine, and it was off to the races. (The chapter on advertising in Brad Stone’s Amazon Unbound is excellent.) By 2019, Amazon had emerged as a clear 3rd-place to Google and Facebook, growing quickly:

Now Amazon is a top-5 global business by advertising revenues.

Looking at 2022 data vs. that ~2020 data, Amazon’s ad revenue is already up to $30B+. Amazon is a certified advertising behemoth.

On to the second type of shopping: discovery-driven shopping.

Discovery-driven shopping is the mall. It’s wandering around, browsing, deciding what you might want to buy. Discovery-driven shopping is about serendipity.

But discovery-driven shopping is more difficult online. Amazon, for one, is terrible at it. Rather, social platforms have become the nuclei of discovery commerce, with Shopify providing the plumbing underneath. In one of my first Digital Native pieces over two years ago, I made this chart to illustrate the two forms of shopping:

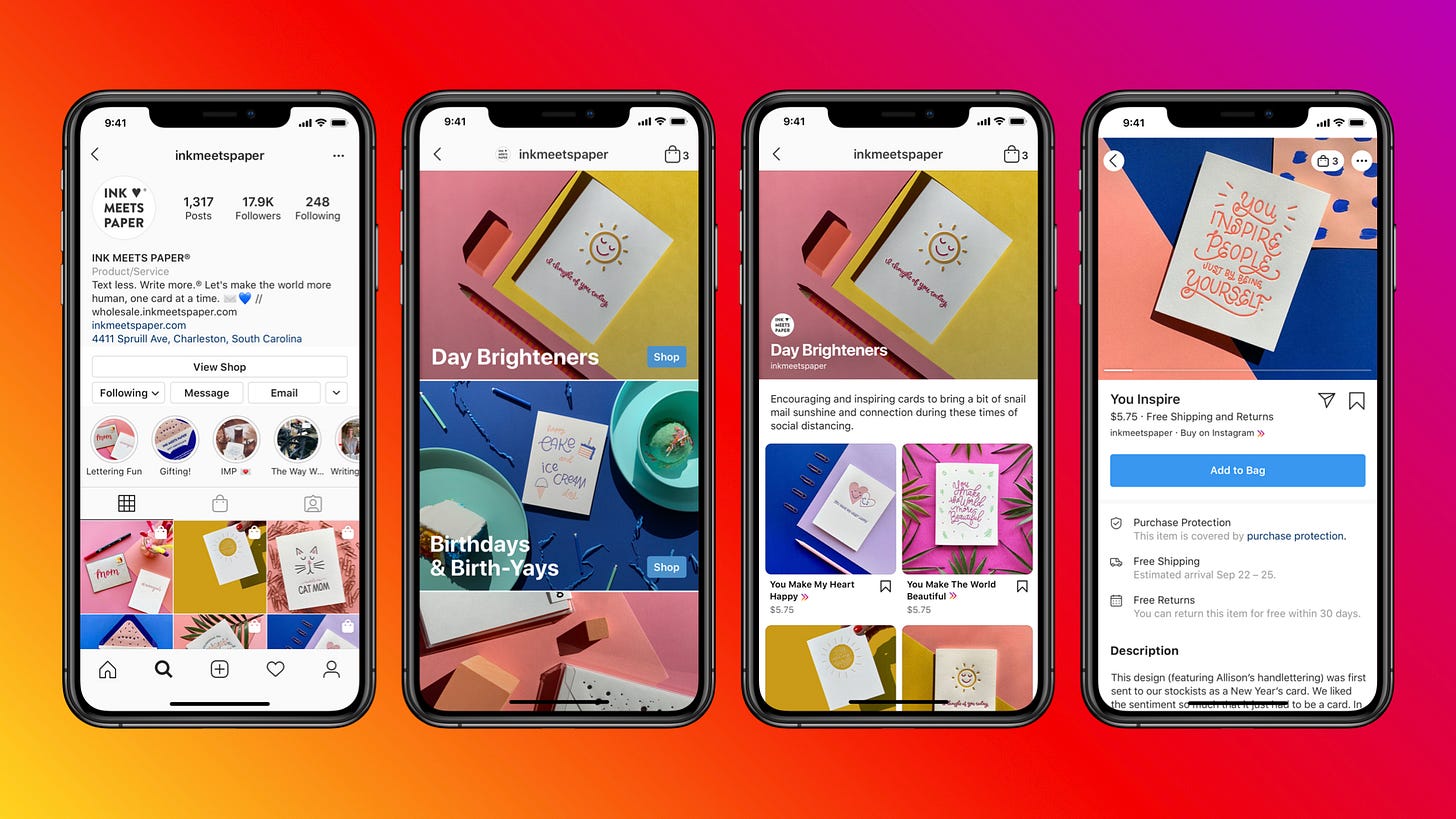

That piece was effectively an argument for Instagram to go all-in on commerce, mirroring China’s Xiaohongshu in social commerce. In the U.S., social commerce hasn’t taken off to the same degree as in China; rather, commerce seems to be layered on top of existing social platforms (Instagram, Pinterest, Facebook Marketplace), rather than companies blending social + commerce from the get-go. (One interesting development: Pinduoduo, the largest social commerce company in China with 800M users, announced yesterday that it’s about to enter the U.S. market.) Instagram, as a visual platform built on aspiration, is a logical destination for discovery-driven commerce. But Instagram Shop has stalled, and Instagram seems more focused on its all-out assault on TikTok with Reels.

This leaves a key gap in discovery-driven shopping, which we’ll get to later.

PRESENT

Advertising and commerce are two sides of the same coin; you can’t have one without the other. And there are two types of advertising worth knowing: direct response advertising, which has the goal of making a transaction happen then and there, and brand advertising, which has the goal of building brand equity.

The Tide example above illustrates the difference between the two. If Tide paid per click on its suggested search result, that would be direct response advertising (specifically, it would pay-per-click advertising). The TV commercials that build general awareness of Tide, meanwhile, are brand advertising. You can think of direct response as more immediate, while brand advertising is more of an enduring, slow burn use of ad dollars.

I’ve been doing a lot of furniture shopping lately for my new apartment. Here’s an example of direct response advertising: when I search Ruggable rugs, Google instead serves me a sponsored placement for Rugs USA, a direct competitor to Ruggable in the “washable rugs” category. The second result, also paid, is for Ruggable itself.

The classic example of brand advertising, meanwhile, is Coca-Cola. Coke doesn’t care that you buy that Coke right now, but rather that next time you’re thirsty at a movie theater, you reach for a Coke and not a Pepsi. Companies like Nike and Disney also rely heavily on brand advertising, building long-term brand equity.

Direct response is where most of the money is in digital advertising, which makes sense—direct response drives real outcomes for brands, and it’s highly measurable. Direct response lends itself naturally to the internet, where attribution is easier than with TV or physical advertising like billboards.

Most estimates have direct response comprising about 80% of all digital ad dollars spent online. Facebook, Instagram, Snap, YouTube, and now TikTok have followed a predictable migration from brand to direct response. YouTube’s rapid revenue growth in the past few years is partly related to its shift to direct response, which still only makes up an estimated 20-30% of its revenue. TikTok, for its part, is currently making a huge effort to build out direct response. Twitter, unfortunately, never quite figured out direct response, which is a key reason its share price is up only +3% since IPO compared to Facebook’s Meta’s +300% gain.

But the customer acquisition engine is breaking. Meta, Google, and now Amazon have a stranglehold on the digital advertising market, and even digital real estate is finite. CACs are consistently rising. The direct-to-consumer brand movement was built on direct response advertising, facilitated by the internet. All of a sudden brands didn’t need wholesale. But most DTC brands will eventually hit a plateau: for instance, you might hit $20 million in revenue when all of a sudden, your CACs creep up from $100 to $200; and if the LTV (lifetime value) of your customer is only $175, the math just doesn’t make sense.

During the 2010s DTC boom, a popular saying became “CAC is the new rent.” Rather than acquiring customers with geography (“Oh, what’s that new store over there? Let me check it out!”), DTC brands relied on direct response ads. But when CACs got too high, DTC brands opted to go the old-fashioned route: brick-and-mortar locations. All of a sudden, every gentrified street in America had a Casper showroom, an Everlane store, a Warby Parker location, an Outdoor Voices outpost, and so on.

Brands like Warby Parker and Jessica Alba’s Honest Company now get 50% or more of their revenue from physical retail locations:

Alongside rising CACs, Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) changes have dealt a blow to digital advertising. ATT is Apple’s opt-in privacy framework that requires all iOS apps to ask users for permission to share their data. Spoiler alert: many people do not opt in. Meta estimates that it will lose $10 billion in ad sales revenue (about 8% of its annual revenue) because of ATT. When the company announced that, the stock plummeted 26%—$230 billion of market cap wiped out in one day.

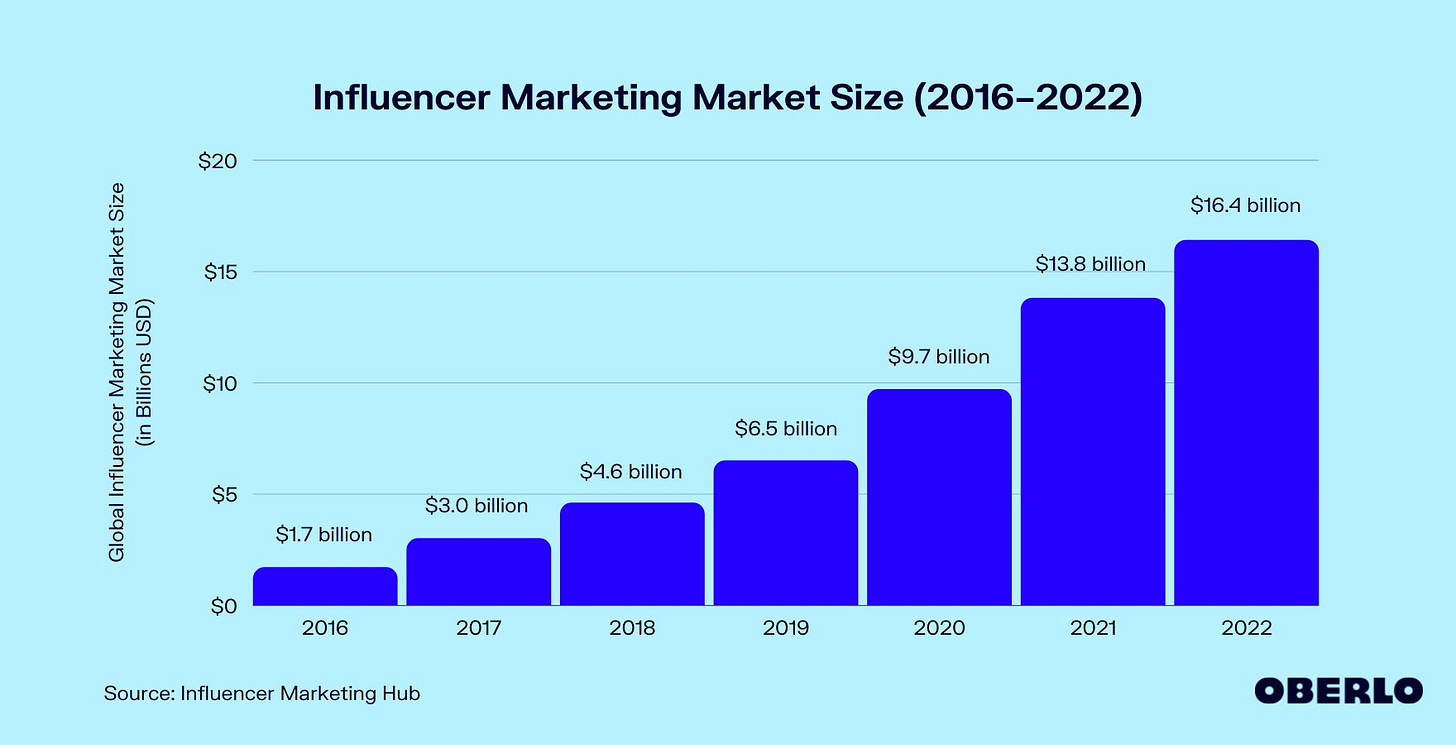

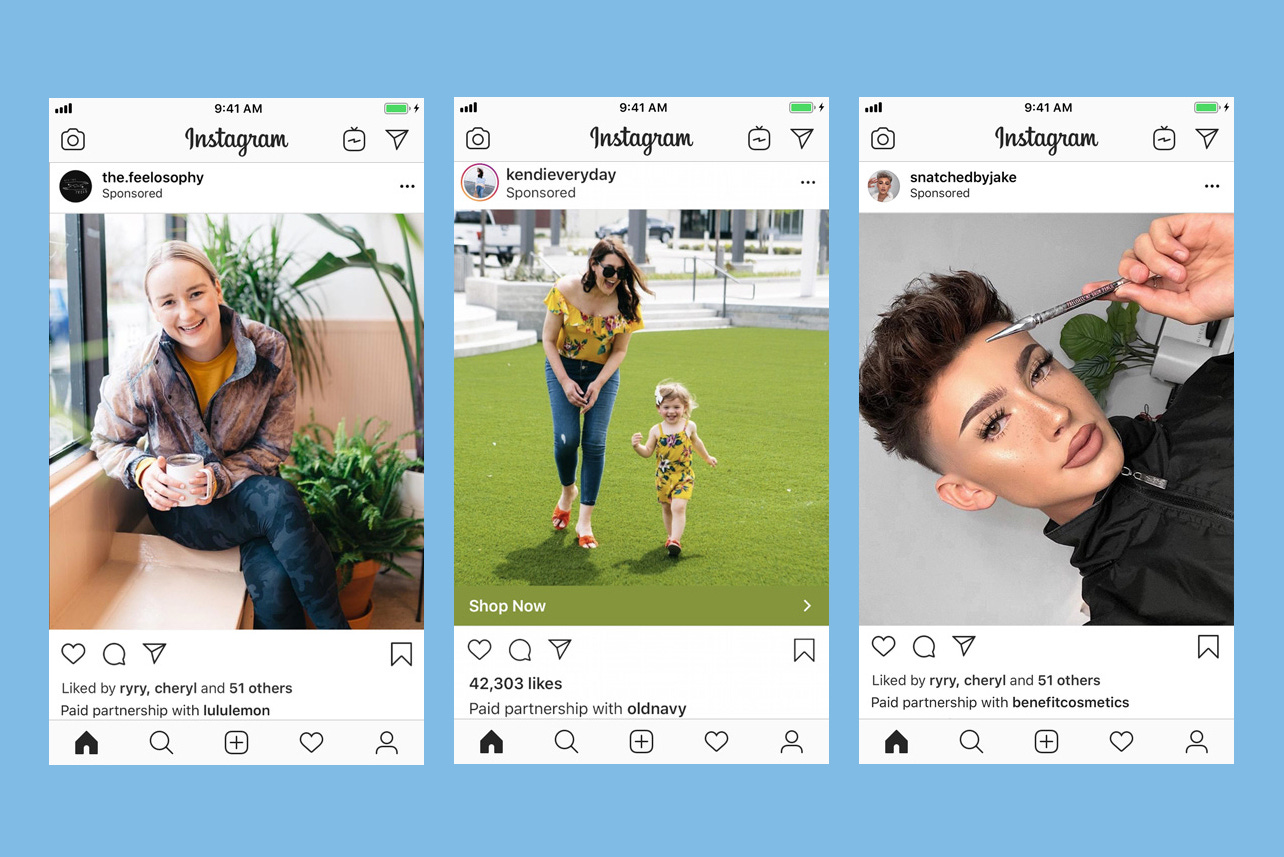

Meta and Google are becoming more expensive and less measurable for brands, leading brands to start exploring new customer acquisition channels. Influencer marketing is one option, and the industry has swelled from $1.7 billion in 2016 to $16.4 billion in 2022 (a 46% CAGR). Influencer underpins discovery-driven commerce.

But influencer marketing is also broken. As I wrote in May’s Influencer Marketing 2.0, most influencer campaigns rely on hefty upfront lump-sum payments and use hacks like discount codes to track attribution. ROI is often poor, and measurement is even worse. The channel is difficult to scale efficiently.

But with brands hungry for new customer acquisition channels, something needs to give. And that brings us to how the commerce and digital advertising worlds will respond to rising CACs and privacy changes.

FUTURE

The old playbook—spin up Facebook Ads Manager, sprinkle in some SEO and SEM, maybe experiment with an influencer campaign—doesn’t work anymore. That playbook is now too expensive and too difficult to measure. Brands need to get savvy about efficiently acquiring customers in what’s become the new normal for commerce/advertising.

Brands need new channels. One opportunity: creators.

If Target and Walmart were the wholesale retailers of the 20th century, creators are the wholesale retailers of the 21st. Creators aggregate demand for a variety of products in a single cohesive digital destination. To return to me furnishing my apartment—in 1985, I might have gone to Macy’s and Sear’s at the mall to buy stuff; in 2022, I instead follow a bunch of home decor influencers on Instagram and shop their recommendations.

We recently invested in a company that enables creators to be the next-generation sales channels for brands, in a transparent and privacy-forward way. Brands care about a few things: 1) They only want to pay when they’ve acquired a new customer and done so profitably; 2) They want to control who can sell / promote their brand and where; and 3) They want the ability to measure what’s working and know what’s worth doubling down on. This company gives brands all three.

If you work at a brand or if you run a brand that’s struggling with customer acquisition, send me an email at rex.woodbury@indexventures.com 📬 I’ll put you in touch with our portfolio company.

Final Thoughts

The internet revamped the age-old process of connecting brands and customers. It’s no longer as simple as wandering the market in your town square, or driving to your local mall to browse shops. Brands are competing for customers in a complex, expensive, and always-evolving digital environment. In a recession, customer acquisition efficiency becomes even more paramount.

But the evolution of the internet also presents new opportunities: now is one of the most interesting times in commerce history to reinvent the playbook for acquiring customers. The 2032 customer acquisition playbook will look dramatically different than the 2022 playbook.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Anti-Amazon Alliance | Ben Thompson

Apple’s Privacy Features Will Cost Facebook $12 Billion | Forbes

Statista, eMarketer

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: