Came for the AI Tool, Waiting for the AI Network

Why are AI creative tools single-player, and will that change?

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 70,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Hey Everyone 👋,

This week we hit 70,000 subscribers. We also recently hit the 5-year mark for Digital Native. Thanks for following along! To celebrate, let’s talk about AI music videos and debate whether AI creative products will be tools or networks.

Without further ado…

Came for the AI Tool, Waiting for the AI Network

One of my good friends is the mastermind behind an Instagram account called PopDaddy AI.

What is PopDaddy AI, you might ask? Well, as the Instagram bio would tell you: Pop Daddy is “honoring pop girls with the highest form of praise—unhinged fan fiction made with love.” What does this mean in practice?

First, it means that gay men spend way too much time thinking about female pop stars (guilty as charged). Second, it means that PopDaddy is using the latest AI tools to create AI-generated music videos. The account first blew up with a mash-up of Lady Gaga and Taylor Swift singing the former’s new song, “How Bad Do U Want Me.” Besides being the song of the summer (you heard it here first!), “How Bad Do U Want Me” is a song from Gaga’s recent Mayhem album that sounds straight off Swift’s 1989. PopDaddy’s video inserts the two pop divas into an AI music video, complete with motorcycles, explosions, and a convertible driving off a cliff into the Grand Canyon. You can check out the masterpiece here.

Why are we talking so much about a fake music video? 🤨

Well, this is how most people will use AI. We’ve written ad nauseam about AI agents in the workplace. That’s the corporate use case. But outside of work, what will be the tools that are commonplace, that are used by billions of people every day? Creative tools.

Naturally, I became interested in how my friend was making the videos. Thankfully, he outlined his creative process. Here’s his stack:

ChatGPT

Kling AI

Midjourney

Adobe Photoshop

Kling AI again

Let’s quickly break down how he makes a single scene using these tools:

1) ChatGPT

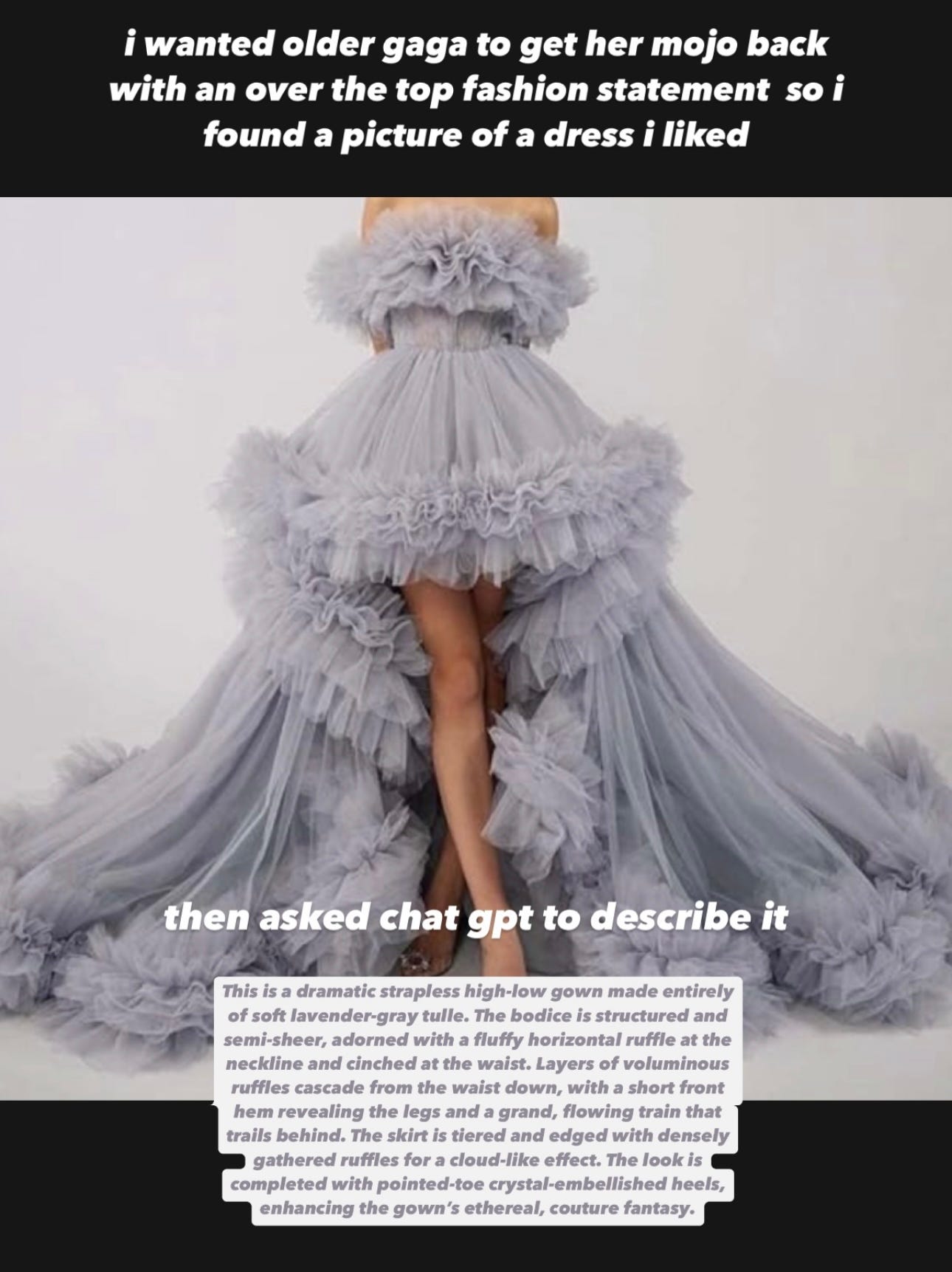

First, my friend will decide his vision. Say he wants to put Gaga in a beautiful gown. He finds a dress he likes online, then asks ChatGPT to describe the dress. ChatGPT spits out a description:

2) Kling AI

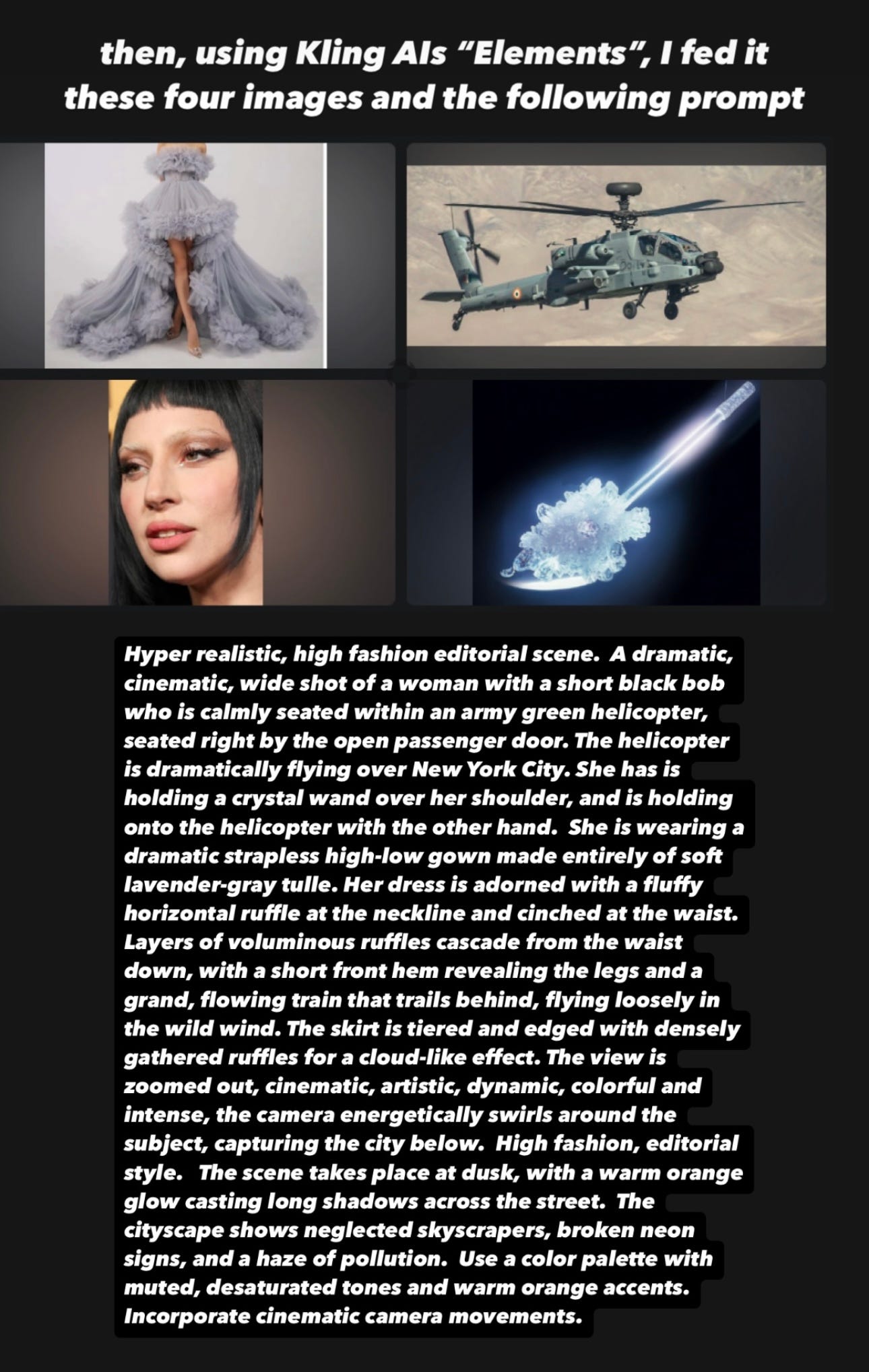

He then has a vision for putting Gaga in a helicopter. He uses Kling’s “Elements” feature to feed the model four elements and a prompt.

Kling doesn’t do the best job here, unfortunately.

3) Midjourney

So he turns to Midjourney for a better image. The same prompt leads to this:

4) Adobe Photoshop

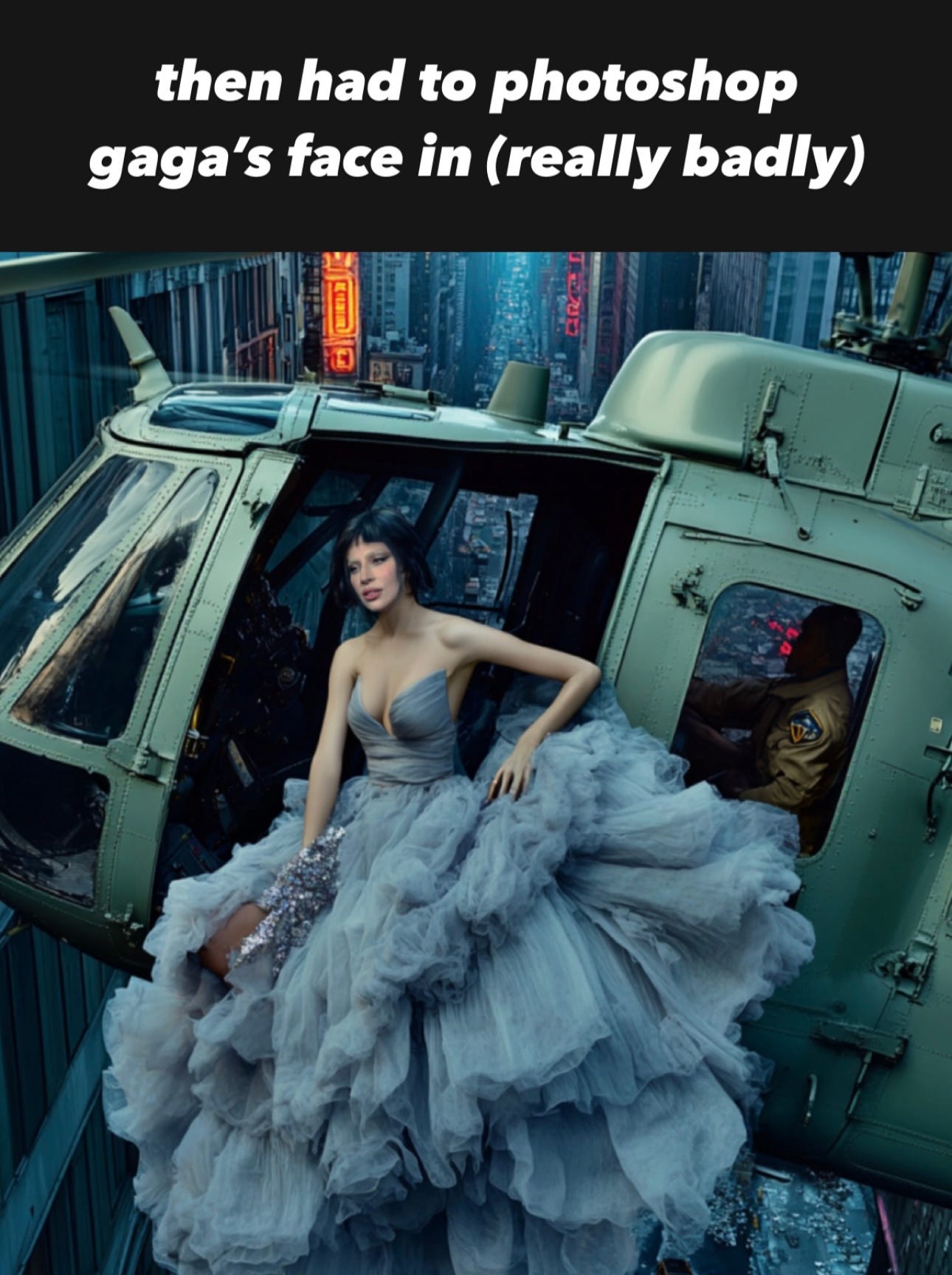

He uses good old Photoshop to get Gaga’s face in there.

5) Kling AI again

And as a final step, we’re back to Kling, which is much better at animating an image than actually creating that image.

Voilà, we have a scene for the music video.

Bending the Arc

Most people won’t dedicate hours to painstakingly crafting fake music videos. My friend is special that way (in the best possible way). But most people will use AI tools to make stuff. And they can make that stuff more quickly, more cheaply, and of higher quality than in past technology eras.

This is a long-standing thesis in Digital Native: the arc of technology bends toward more accessible tools and higher quality output. This isn’t anything new. Way back in 2015 (yes, that’s already 10 years ago), Steven Johnson wrote in The New York Times:

The cost of consuming culture may have declined, though not as much as we feared. But the cost of producing it has dropped far more drastically. Authors are writing and publishing novels to a global audience without ever requiring the service of a printing press or an international distributor. For indie filmmakers, a helicopter aerial shot that could cost tens of thousands of dollars a few years ago can now be filmed with a GoPro and a drone for under $1,000; some directors are shooting entire HD-quality films on their iPhones. Apple’s editing software, Final Cut Pro X, costs $299 and has been used to edit Oscar-winning films. A musician running software from Native Instruments can recreate, with astonishing fidelity, the sound of a Steinway grand piano played in a Vienna concert hall, or hundreds of different guitar-amplifier sounds, or the Mellotron proto-synthesizer that the Beatles used on ‘‘Strawberry Fields Forever.’’ These sounds could have cost millions to assemble 15 years ago; today, you can have all of them for a few thousand dollars.

We’ve seen more examples in recent years. When Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” set the record for longest-running #1 hit a few years back, the song’s beat had been bought on BeatStars for $30. Last year’s Sabrina Carpenter smash “Espresso” used a beat built from Splice loops. Best Picture-winning movies have been edited on Final Cut Pro, which you and I can buy for $299. And so on.

AI supercharges cultural production, and tools are improving at an exponential rate. Just a year or two ago, creative tools were struggling with human fingers. Now, I can’t even remember the last time I saw a six-fingered hand. One viral TikTok video shows Harry Potter characters at a techno-rave; this comment sums it up well:

Just this week, I sent a message to my group text about Katy Perry’s stunning red carpet look at the Met Gala:

Only a day later did I realize that this was AI-generated, and Perry wasn’t even at the Met Gala. (This was the second year in a row that Perry fooled me. Fool me once…)

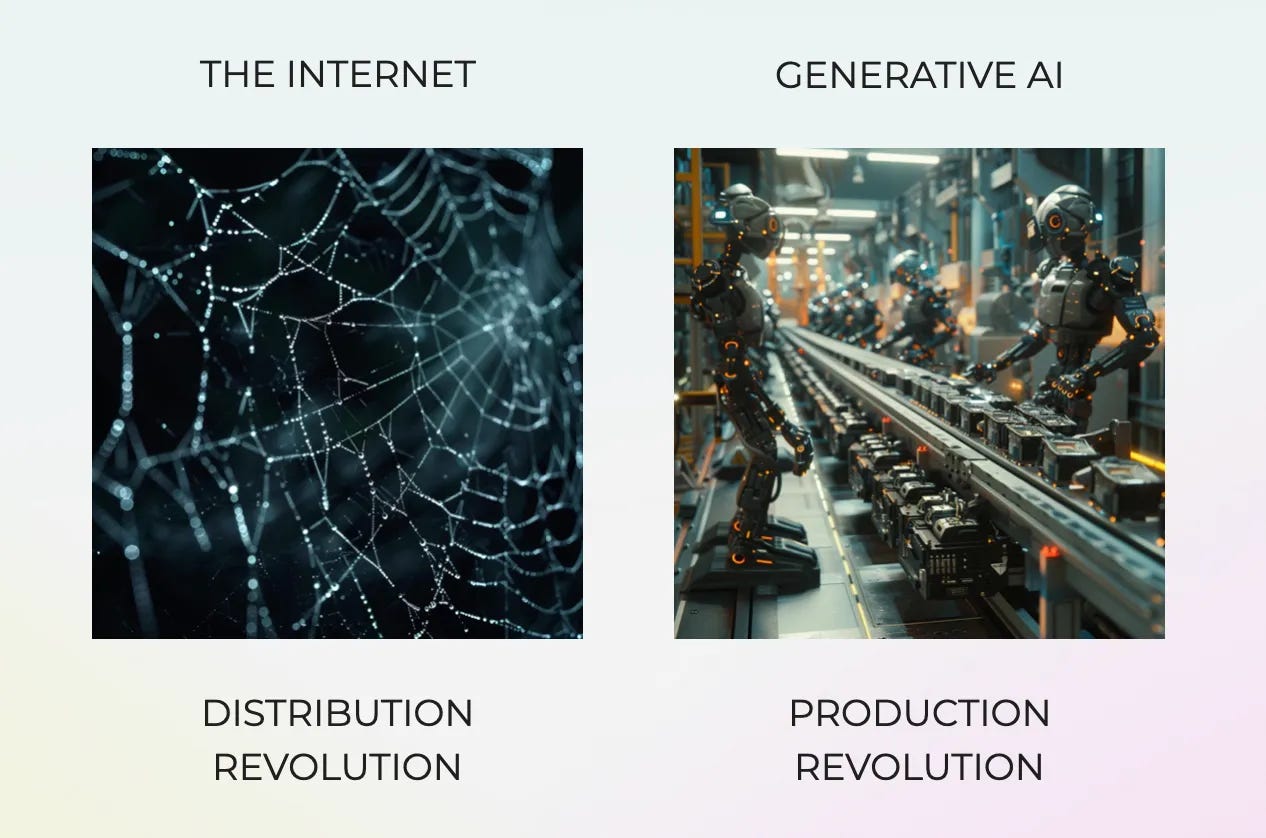

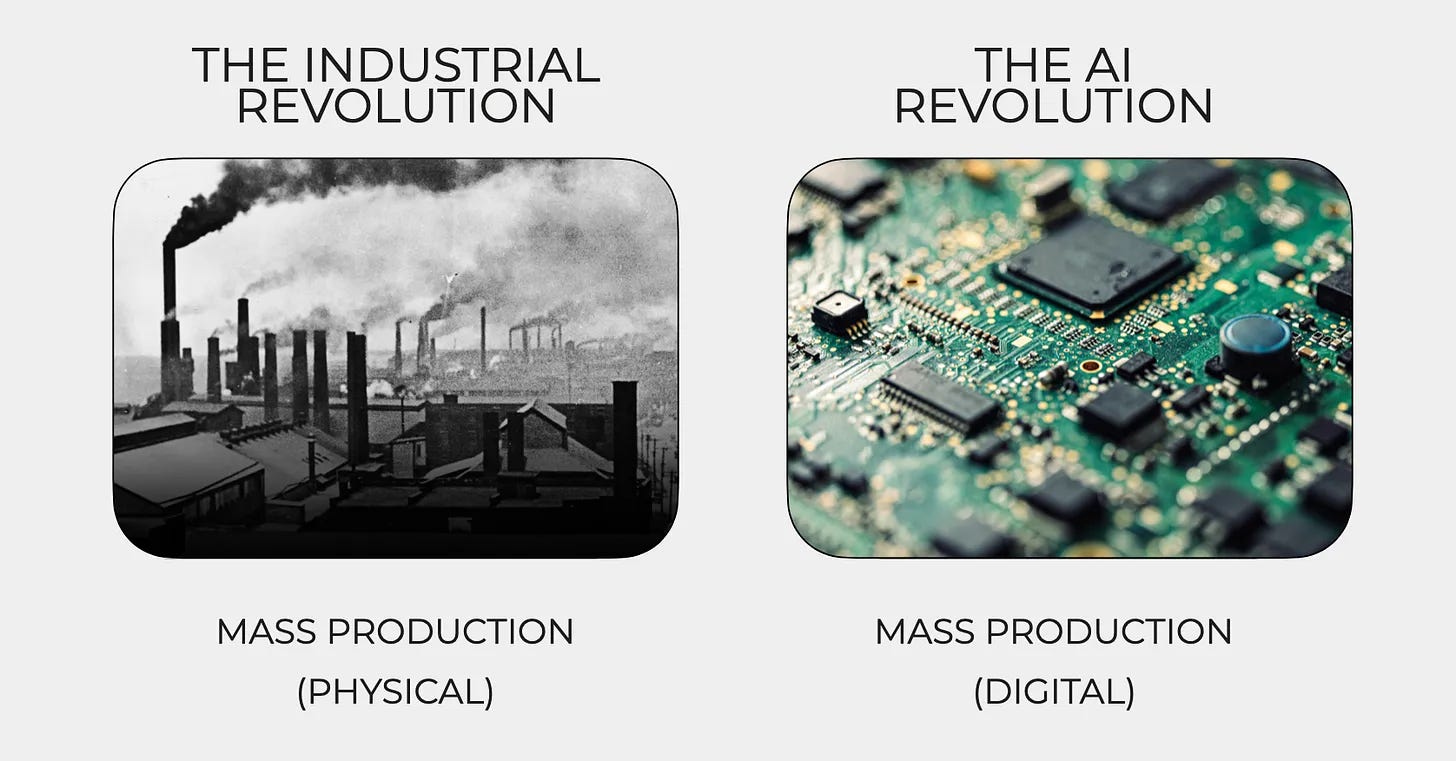

In last year’s Weapons of Mass Production, we argued that AI is a production revolution similar to the Industrial Revolution, but this time encompassing digital production.

Every month, the speed of creation is accelerating and the cost of creation is decreasing. The big creative industries are changing rapidly.

But the problem right now is that creative tools are just that—tools. Where are the networks?

“Show me the networks!”

Let’s take an example. A recent viral trend was the “Starter Pack” trend. This basically encompasses people generating an image of themselves that resembles an action figure inside the packaging. Here’s my Starter Pack:

Fun stuff. Once I have the image, there’s plenty I can do with it.

Say I want to animate the image and add audio. I’ll use Hedra, which is my favorite creative tool (I think it’s better than Kling). I upload my image and add a prompt:

I want to animate this image so that the person walks out of the packaging and begins walking toward the camera. They should smile and swing their arms, and maybe take a sip out of their coffee.

I add a short audio script and boom—we have a walking, talking action figure Rex:

AI tools are mind-blowing and they’re progressing nicely. But the challenge isn’t in the tooling. The challenge is in the frictions around (1) inspiration, (2) sharing, and (3) remixing.

I’ve seen dozens of “Starter Packs” across social platforms. But in order to figure out how to make my own, I had to go down a rabbit hole. Eventually I found a TikTok video explaining what prompt to use, and with some trial-and-error got the half-decent output above. But why did it take me 10 minutes to track down the prompt and figure out how to do it?

This is because AI tools are single-player, like Photoshop or Final Cut, and not networked platforms like TikTok or GitHub.

This limits sharing. When I’m done with my Starter Pack, there’s no natural place to share my creation, apart from old-school networks. Worst of all, no one can remix my creation. Content is meant to be remixed; TikTok’s entire premise is on remixing (Duets, Stitches, trending sounds, and so on). AI tools should learn from that.

OpenAI is a research entity and enterprise company that happened upon the fastest-growing consumer product of all time in ChatGPT. But ChatGPT isn’t built like a networked, social consumer application. It’s built like a productivity tool.

The question for AI creative tools: will they remain single-player, or will they become networks over time? Today’s tools are designed for solo workflows, which allows them to supercharge productivity. But their solo nature limits serendipity, remix culture, and feedback loops.

On TikTok, every piece of content is a node in a network. AI outputs should also live in a network. Imagine creative tools that let you remix other people’s AI videos, fork a prompt and iterate on it in public, collaborate with others in real-time, watch creation in process a la Twitch. There’s a lot left wanting in the 1.0 tools we have today.

I made an analogous argument in February’s The ChatGPT Prompts That Can Be $1B+ Companies. Why should we have to discover great prompts on Twitter, Reddit, TikTok? There should be network features where we can see creators’ prompts, then go build on them and personalize them. Prompts like the Starter Pack should go viral on ChatGPT, or at least on an AI-native platform! Kling, Sora, Midjourney, Hedra, etc. are tool-centric, not creator-centric. There’s no native follower graph, reputation system, or creator identity built into the tools. These tools are built like Adobe products, not like creator networks.

Final Thoughts

When GPT-4o came out last month, Studio Ghibli images were everywhere on Twitter. But should a meme go viral across the same platform on which it was created? This is a key question over the coming years—do AI tools become networks, or do existing networks integrate AI tools? The title for this piece, of course, is a nod to Chris Dixon’s 2015 blog post “Come for the tool, stay for the network.” (By the way—OpenAI is clearly thinking about this: Twitter competitor is reportedly in the works.)

Again, not everyone will go through the trouble of PopDaddy AI’s creative process. But that process will be much simpler in a few years: it might live in a single tool, and a single prompt might glean a rich, visually-arresting music video.

Two questions to ponder as we wrap up:

One, how will the growing AI backlash affect creative tool adoption?

Demi Moore recently had to apologize for hopping on a popular trend: seeing what AI thinks your pet looks like as a human. Seems innocent enough, but Moore had to say sorry to angry fans who lashed out about AI being “wasteful” and “unethical.” Just last week, Duolingo’s CEO came under fire for saying his company will be—gasp!—“AI-first.” And people recently got angry when Sam Altman said that saying “please” and “thank you” to ChatGPT is costing OpenAI millions (and thus creating environmental damage). It’ll be interesting to see how rejection of AI adoption (which seems to skew younger?) collides with AI’s invasion of creative tooling.

The second question: do AI tools enhance or erode the quality of cultural outputs?

A good read in The Atlantic this week wonders whether this is the “worst-ever” era for American pop culture. Americans seem to think so. From the article:

According to a recent YouGov poll, Americans rate the 2020s as the worst decade in a century for music, movies, fashion, TV, and sports. A 2023 story in The New York Times Magazine declared that we’re in the “least innovative, least transformative, least pioneering century for culture since the invention of the printing press.” An art critic for The Guardian recently proclaimed that “the avant garde is dead.”

What’s so jarring about these declarations of malaise is that we should, logically, be in a renaissance. The internet has caused a Cambrian explosion of creative expression by allowing artists to execute and distribute their visions with unprecedented ease. More than 500 scripted TV shows get made every year; streaming services reportedly add about 100,000 songs every day. We have podcasts that cater to every niche passion and video games of novelistic sophistication. Technology companies like to say that they’ve democratized the arts, enabling exciting collisions of ideas from unlikely talents. Yet no one seems very happy about the results.

We have more art and content than ever, but we’re somehow in a cultural dark age? I don’t buy it. My view is that people love to hate on the present (fear-mongering, hand-wringing).

I take the more optimistic view: AI tools will supercharge creativity. We’ll get more content—a lot more—and sifting through it for quality will be a challenge. But lower barriers to creation are a good thing. Who doesn’t want more music videos of our pop icons?

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: