Lessons from China's Tech Innovation

Plus, shorter pop songs, tech in 2030, and Instagram vs. TikTok

This is a newsletter about how tech is changing how we live and work

To receive this newsletter in your inbox weekly, subscribe here 👇

Learning from China’s Innovation

I was recently talking with a Chinese friend who told me that the American tech ecosystem and the Chinese tech ecosystem have one fundamental difference: while innovation in the U.S. has focused on underlying tech, innovation in China has centered around business model shifts.

For the most part, I agree with him. His point is that Silicon Valley has created great advances in search, mobile, AI, and so on, while China's tech giants have found new ways to monetize technology and new ways to get consumers to interact with technology. I'm going to share some of the most interesting examples of innovation in China, and what we can learn from them.

Much of this content comes from Connie Chan, who I deeply admire and recommend following. I link to some of her pieces below.

Monetization & multi-modal business models

Big tech companies in the U.S. typically fall into one of two camps: their business model is based on advertising, or it’s based on subscription. For advertising, think Facebook, Google, Instagram, Snapchat, Pinterest, Yelp, and YouTube. They compete in the eyeball economy. For subscription, think Netflix, Spotify, Amazon Prime, and Apple Music. They compete in the wallet economy. This singular focus has its downsides: for example, experts predict that the average American is bombarded by 6,000 ads a day.

Chinese companies have embraced multi-modal business models. Tencent, for example, makes only 20% of its revenue from ads. It is incredibly disciplined, showing its one billion WeChat users only two ads each day. Meanwhile, 40% of revenue comes from gaming, 20% from services like livestreaming, and 20% from payments. This diversification is partially because Chinese tech companies came of age on mobile (largely leapfrogging the desktop), and ads are more intrusive on mobile; as a result, companies were forced to innovate new ways to monetize.

Influencers

In the U.S., influencers largely monetize in one way: advertising. In China, influencers become the brands. There's a Chinese company called Ruhnn that IPO'd last year. Ruhnn incubates influencers, hand-picking promising young social media users and grooming them to become online celebrities with hundreds of millions of followers. Once the influencer is large enough, Ruhnn creates a store for the influencer on Taobao.

An influencer can make clothing in real-time, livestreaming with followers and asking for design advice and taking orders. She then orders the exact inventory and ships items to her followers. Ruhnn's top influencer, Zhang Dayi, has 15 million followers on Weibo and last year did $90M in sales by herself.

This is much more advanced than the U.S. influencer economy. While there are additional challenges in the U.S. (more expensive manufacturing, for one), I see no reason a similar incubator can't work here in the states.

Books

In the U.S., tech has made books available online, but it has stopped short of reimagining what a book can be.

In China, books are created and sold tech-first. For many books, the first two-thirds are available for free on mobile; readers must only pay to unlock the ending. And in a different but increasingly common model, books are sold as bite-sized snacks, typically per 1,000 words. Readers only keep paying if they like the book. Readers are also able to give the author real-time feedback; the next "chapter" can incorporate immediate feedback from fans. This is leading to ever-longer books (leading to much better economics for the authors): one of last year's most popular books is ongoing, but has reached 10,000 chapters and is 46 times as long as the entire Harry Potter series.

These are only a few examples of how China has innovated new ways that technology can be used in consumers' lives. In the U.S., we can learn from this creativity to leverage tech in more groundbreaking ways.

Sources & Additional Reading — here are the pieces that inspired and informed this content; check them out for further reading on this subject:

Connie Chan is the leading thinker on this topic in Silicon Valley — read all her posts here

Online to Offline 2.0 (Connie Chan, a16z)

When Advertising Isn’t Enough (Connie Chan, a16z)

Chart of the Week

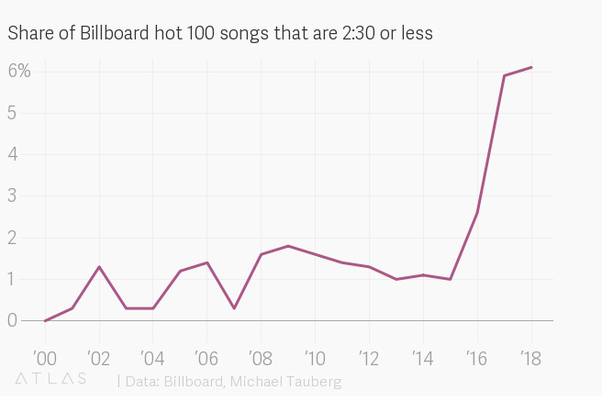

The number of short songs on the charts is dramatically increasing. Old Town Road, the biggest hit of 2019 and the longest-running #1 song in history, is only 1:53 long. (For comparison, the average song length of all #1 hits ever is 3:48.) This is driven by streaming economics: artists are compensated per stream, and number of streams is an increasingly important metric in chart rankings. In other words, one play of a 2-minute song will earn an artist the same amount as one play of an 8-minute song.

Tech

Tech in 2020: Standing on the Shoulders of Giants (Benedict Evans)

Where is tech today, how did we get here, and where are we going? This is a detailed and insightful presentation from Benedict Evans, one of the industry's leaders. It still amazes me that of 5.5 billion adults on Earth, 5 billion have a phone and 4 billion have a smartphone. Evans rapidly goes through major sources of disruption: retail (even though less than 15% of commerce is online), media (streaming wars!), facial recognition, deepfakes, and future regulation.

Imagining the Future of Tech (Frank Chen, a16z)

Frank Chen of Andreessen Horowitz imagines what a day in the life of his daughter, Katie, will look like in 2030. His innovative presentation includes a smart toilet that tracks Katie's glucose, personalized nutrition in meals delivered by robots, and the ability to buy shares in your favorite influencer. While the video admittedly overlooks some of the darker implications of new technologies, it's difficult to watch this video and not be both optimistic about and excited by our future.

Commerce

Why It Only Costs $10K to Open a Chick-fil-A (The Hustle)

Alex Taussig noted this in his writing this week — it’s fascinating. Chick-fil-A rakes in $10 billion each year, putting it behind only Starbucks and McDonalds as the country’s 3rd-largest restaurant chain. Behind its success is a unique franchise model. Most fast-food chains require franchisees to invest $1-2 million to open a location. Chick-fil-A only requires owners to put in $10K, and finances the rest. And they are more selective with franchisees: they target franchisees who are deeply involved in their local communities, which brings regular traffic into stores. In return, Chik-fil-A charges a higher rake (15% vs. 4-8% for competitors) and keeps half of profits.

The Economics of Ski Resorts (Wendover Productions)

I love Wendover Productions' YouTube videos and recommend them all. In his most recent video, he explores the complexities of operating a ski resort—probably the most seasonal business you can have. A side-effect of combining low-wage labor and sky-high real estate: some of the best public transit in the country.

Shopify, the E-Commerce Company That's Coming for Amazon (Vox)

Every day, millions of customers shop online for Allbirds, Kylie Cosmetics, or one of the other 500,000 brands on Shopify. And they have no idea that they're using the platform. Shopify is, in my opinion, the most underrated tech company. What started as a company to help sell snowboards online now has a market cap of $62 billion. Exactly one year ago today, its market cap was $19 billion. (That's a +326% year-over-year increase!) This week, Shopify announced that it did $61B in GMV in 2019, up 47% from 2018. And they're just getting started with powering online commerce: last year, Shopify announced a push to build a nationwide logistics network.

Media

The Instagram Aesthetic is Over (Taylor Lorenz, The Atlantic)

Bright walls, latte art, avocado toast. We may look at 2019 as "peak Instagram aesthetic." (Personally, I'll always think of The Museum of Ice Cream as emblematic of this era.) While this trend isn't gone just yet, it's definitely on the decline; Gen Zs reject its gloss and curation in favor of authenticity and spontaneity. Which brings us to....

Hype House: A Los Angeles Mansion Full of Teenage Tik Tok Celebrities (NYTimes)

Tik Tok is taking over the world. The app was downloaded more than the Facebook and Messenger apps last year and nearly two-thirds of users are under 25. This highly entertaining piece profiles a mansion in LA full of teenage creators who have achieved Tik Tok fame.

Sam Lessin wrote about Tik Tok for The Information this week, and perfectly captured the shift we're seeing from the Instagram aesthetic to the ethos of Tik Tok. It's worth subscribing to read the entire piece, but here is a brief portion. Sam explains why creation on Tik Tok (spontaneous, low production value, social) is so different than creation on Instagram.

There was a moment in Hollywood when silent films were on the way out and talking films were taking over. As the mythology goes, there was huge turnover among film actors because delivering lines required new and different skills.

TikTok feels like a version of that playing out for the digital age.

One of the problems with a lot of social media is that because it is identity-centric, the social game that plays out digitally mirrors the social game of reality, where wealth and physical attractiveness win. The biggest influencers are the most beautiful and richest people, because they typically produce the best images and have the biggest clout.

TikTok’s format of videos shakes up that formula, because the most beautiful and richest people don’t necessarily produce great video content.

To receive this newsletter in your inbox weekly, subscribe here 👇😊