The Splintering of Media

The Shift from Mainstream News to Echo Chambers

This is a weekly newsletter about how people and technology intersect. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

The Splintering of Media

When I think of media today, I think of the cafeteria map from Mean Girls.

For those unfamiliar with Mean Girls, (1) I question your priorities in life, and (2) I’ll provide a brief recap. Cady—played by Lindsay Lohan—has been homeschooled her entire life. She arrives at North Shore High School as a bewildered junior, helpless to navigate the school’s unspoken social code.

Janice and Damian take Cady under their wing and give her a map of the school cafeteria, which doubles as a map of school cliques and fiefdoms.

This map reminds me of social media today. Different “cliques” with different worldviews and different life experiences are segmented into their own spaces. There’s little interaction between silos and when there is, it isn’t pretty.

Last week’s horrific events at the Capitol were the latest evidence of historic levels of partisanship and vitriol, for which social media has been a key catalyst.

In We’re All Social Distancing on the Internet Too, I argued that we’re becoming more divided in every aspect of culture. We’re watching different shows on Netflix. We’re listening to different music on Spotify. We all have different For You Pages on TikTok.

But this phenomenon applies most acutely to news media, which has devolved from mainstream to insular. In President Obama’s final speech as president four years ago, he warned America about this shift:

“For too many of us, it’s become safer to retreat into our own bubbles, whether in our neighborhoods or college campuses or places of worship or our social media feeds, surrounded by people who look like us and share the same political outlook and never challenge our assumptions. The rise of naked partisanship, increasing economic and regional stratification, the splintering of our media into a channel for every taste—all this makes this great sorting seem natural, even inevitable. And increasingly, we become so secure in our bubbles that we accept only information, whether true or not, that fits our opinions, instead of basing our opinions on the evidence that’s out there.”

The internet magnifies and ossifies confirmation bias. We gravitate to people who are like us—people who make us feel good about ourselves. Rather than challenge our beliefs, these people reinforce them.

Given the events of last week and its ripple effects through news media, I wanted to take a deeper look at how we got here and where we’ll go from here.

Let’s start with the era of mainstream news.

1️⃣ Mainstream News

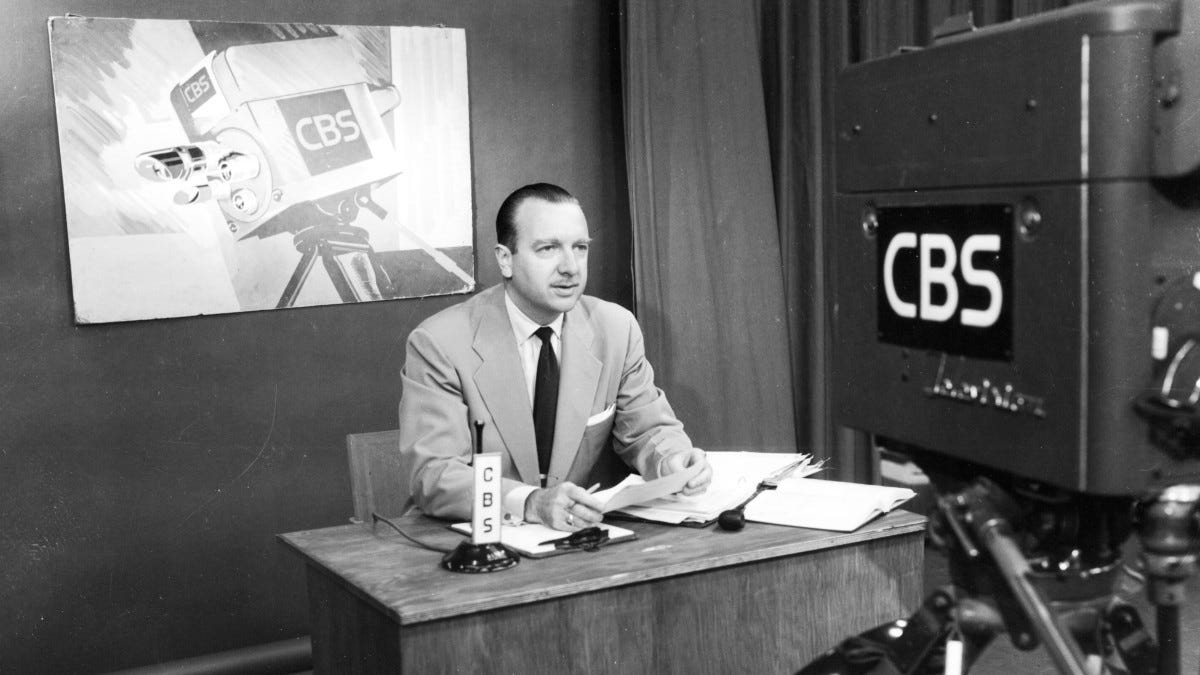

For the 20 years between 1962 and 1981, Walter Cronkite was the anchor for CBS Evening News. He was a daily presence in nearly every American household. In 1972, a national poll found that Cronkite was “the most trusted man in America”, beating out a (pre-Watergate) President Richard Nixon. Fifty years later, the idea that a journalist could be the most trusted man in America is unthinkable.

But millions of Americans trusted Cronkite to report events ranging from the Vietnam War to the Iran Hostage Crisis to the assassinations of JFK and Martin Luther King, Jr. The anchor became synonymous with impartiality; one of his famous quotes is, “In seeking truth you have to get both sides of a story.”

Cronkite became known for his departing catchphrase, “And that’s the way it is”—a phrase that has a certain irony in an age of fake news and misinformation.

The era of the trusted news anchor continued in the 1980s, with the “Big 3” rivalry of CBS’ Dan Rather, NBC’s Tom Brokaw, and ABC’s Peter Jennings. (Rolling Stone chronicles this era in an excellent piece called Anchor Wars, if you’re interested in learning more.)

There were downsides to this model: news came from mostly-old, mostly-white, mostly-male organizations. The internet hadn’t yet broken down archaic power structures or subverted the media gatekeepers.

But the benefit was that Americans got their news from the same sources. Politics, partisanship, and polarization had yet to bleed into journalism.

2️⃣ The Emergence of Fox News

In 1996, Rupert Murdoch created Fox News and hired Roger Ailes as its founding CEO. News media was never the same. Murdoch and Ailes set out to build a conservative news organization, injecting bias into news. It worked: since 2002, Fox has been the most-watched cable news network in America.

The rise of Fox foreshadowed the rise of Trump two decades later. As the Columbia Journalism Review tells it, Fox positioned itself as the network “for the unrepresented, for the outsiders…There is a strain of resentment, of put-upon-ness that pervades almost everything Fox puts on the air.” The irony—first with Fox and then with Trump—is that both were cut from the cloth of the New York media elite, but sold themselves as outsiders and victims.

MSNBC was founded the same year as Fox and became the left’s (much smaller) answer to the Fox juggernaut. Both MSNBC and Fox were never really news shows, so much as talk shows. Their lifeblood was opinion commentators, not journalists—an early omen of the armchair experts that would emerge on Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook.

Anita Dunn, Obama’s director of communications, put it best:

The reality of it is that Fox News often operates almost as either the research arm or the communications arm of the Republican Party…What I think is fair to say about Fox, and the way we view it, is that it is more of a wing of the Republican Party…They’re widely viewed as a part of the Republican Party: take their talking points and put them on the air, take their opposition research and put it on the air. And that’s fine. But let’s not pretend they’re a news organization like CNN is.

CNN, for its part, struggled to find its footing in an increasingly polarized industry. CNN has always been more of a news show than talk show: it employs 3x the number of reporters as Fox. (MSNBC, meanwhile, has almost no reporters; it has half the staff that Fox has and one-sixth that of CNN.)

When Jeff Zucker took over CNN in 2013, he reconfigured the network to compete with Fox and MSNBC. This was the birth of the celebrity journalist—people like Anderson Cooper and Rachel Maddow on the left and Sean Hannity and Glenn Beck on the right.

In today’s news world, it’s nearly impossible to find an impartial TV anchor.

News began to look very different depending on what network you were watching. Fox News Vice President Bill Shine said in 2008 that if Barack Obama became president, Fox would become the voice of the opposition, and he held to that promise.

Here are two examples of how major policies were covered on the networks:

Health care reform:

MSNBC—“A godsend…the Senate bill really does advance the ball.”

CNN—“The type of coverage that this country deserves.”

Fox—“It is absolutely insane…It is the lump of coal in our Christmas stocking.”

Climate change:

MSNBC—“[Sarah Palin is] on the wrong side of history. She’s on the wrong side of science. She’s on the wrong side of politics here.”

CNN—“The United States is falling behind the rest of the world in what some see as the cleanest energy option available, nuclear power.”

Fox—“Stolen emails suggest the manipulation of trends, deleting and destroying of data, and attempts to prevent the publication of opposing views on climate change…”

Just taking a quick breather to remind you to subscribe to Digital Native!

3️⃣ Twitter, YouTube, & Internet Gerrymandering

Internet algorithms took the polarization in TV news and poured fuel on the fire. On every major social platform, echo chambers emerged and then calcified.

The New York Times podcast Rabbit Hole explores how a young man named Caleb becomes ensnared in YouTube’s abyss. Caleb starts by watching conservative political thinkers recommended to him by YouTube’s algorithm. (According to the podcast, videos suggested by the YouTube algorithm drive 70% of watch time.) Soon, Caleb is spending 14 hours a day on YouTube and having more and more extreme views.

Algorithms are the gerrymandering of social media. There are conservative niches, like the one Caleb fell into, and there are liberal niches, like the one dominating my social feeds. Neither is representative of the country. Algorithms—with the help of people like Trump—have led to unprecedented distrust and polarization in mass media:

Traditional news organizations like The New York Times also contribute to this problem. By shifting to subscription models over ad-based models, these companies find themselves serving content that their audience wants to read, rather than impartial journalism. For The Times, this means more liberal content, further entrenching held beliefs.

Substack is another example of the splintering of media. There are benefits to the Substack model: writers have more freedom, flexibility, and economic upside. But it’s also easy to envision a world in which we pay for content that reinforces our worldviews, while shutting out content that challenges those worldviews.

4️⃣ Echo Chambers Become Businesses

The final piece in the splintering of media is what we’ve witnessed over the past months. The echo chambers on Twitter and YouTube have broken off to form their own standalone companies.

Parler emerged from far-right Twitter, and Rumble emerged from far-right YouTube.

When Apple banned Parler from its App Store on Saturday, an app called MeWe rose in its place: Saturday and Sunday alone, MeWe gained 110,200 new installs in the U.S. And proving that there’s still humor in these mostly-humorless times, a misspelled app called Parlor also shot to #1 on the charts, confusing conservatives everywhere.

The rise of far-right social media apps mirrors the rise of Fox: Fox broke off from mainstream news; these apps are breaking off from mainstream social media. There are open-ended questions around what will happen with these apps, now that they’ve been shut out by everyone from Apple to AWS to Twilio. But the trend is definitive: the era of mass media is gone, and echo chambers are the new mainstream.

Where do we go from here?

It’s hard to know the long-lasting effects of Trump being banned from Twitter and Facebook, or of Apple and Google kneecapping far-right apps. We’ll look back at last week as a pivotal moment in the arc of social media.

But there will also be broader changes in the platforms that people turn to for news and for conversations. Startups will try to build socially-conscious news media companies:

River’s founder, Jeremy Fisher, paints a dark portrait of the internet today: “A great example of this is the middle schooler who is doing geography homework, looks that up on YouTube—and then 10 videos later, he or she is a flat Earther.” Fisher hopes to reinvent the newsfeed by recommending articles using AI and machine learning, but prioritizing pieces from “credible sources”.

Telepath is a new social network with strict rules around content moderation. Publishers get a “trust score” to combat misinformation and bad actors are quickly punished or banned. Telepath’s ambition is to create a hate speech-free platform where fake news can’t be distributed.

The Factual charges $5/month or $20/year to curate the best, most credible articles for you each day. The company analyzes how credible a story is based on diversity of sources, factual tone of writing, and author’s expertise, among other factors.

There are also emerging social networks that have an opportunity to avoid the missteps of a prior generation. Clubhouse, for example, could use its free-flowing audio format to break down echo chambers and facilitate deeper conversations between people who wouldn’t otherwise interact or learn from each other.

Final Thoughts

Marshall McLuhan, a 20th-Century media theorist, said, “We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.”

That sentence captures the relationship between technology and news. We started with newspapers and broadcast television, which reached almost everyone. Cable TV came along and made news a little more insular. Then the internet decimated news entirely. We’re now seeing the consequences of our tools shaping us.

The defining companies of the future will be those that help us adjust to the tools we have, and those that build the next generation of tools—hopefully tools that break down echo chambers, combat fake news, and encourage real dialogue between people.

Sources & Additional Reading

Anchor Wars | Rolling Stone

President Obama Warns Social Media Becoming a Threat to Democracy | Vanity Fair

Dumb Like a Fox | Columbia Journalism Review

Hands On With Telepath | TechCrunch

River Raises $10.4M for Privacy-Preserving News Recommendations | Venture Beat

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox each week: