Digitally-Native Jobs, Self-Employment, and the Antiwork Movement

The Revolution Happening in How We Work

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Digitally-Native Jobs, Self-Employment, and the Antiwork Movement

In the 2010s, “the future of work” became a bit of a VC trope. I’m as guilty as anyone. Everyone loves a good buzzword—especially one that can mean everything and nothing at the same time—and “the future of work” was once the buzzword du jour. Caitlin may have put it best:

She has a point 🤷♂️

But I’d argue that the future of work is broader than B2B SaaS. It’s true that during the term’s heyday in the ~2015 to ~2020 period, the term became synonymous with productivity and collaboration software. At Index, we’ve invested in many such companies: Slack and Dropbox, Figma and Notion, Skype and Productboard. The list goes on. More recent investments like Gather, which I wrote about last fall in Building a Better Metaverse: Investing in Gather’s Series B (buzzword alert! 🚨), could also fit in this category: many companies use Gather as their virtual office—their “digital WeWork”—in our new world of remote work.

The last decade brought an unbundling of the monolithic Microsoft Office Suite and G Suite (now Google Workspace), with best-in-class tools emerging for every function:

This created an explosion of SaaS tools. But the proliferation of productivity SaaS became too much: most workers are now inundated by an avalanche of apps.

Back in 2020, I wrote a piece about a new rebundling of work, arguing that the next iconic SaaS companies would stitch together these disparate apps and improve focus and knowledge-sharing. We’ve seen this shift play out with all-in-one workspaces like Notion, knowledge wikis like Guru, and admin “rebundlers” like Rippling (check out John Luttig’s recent piece for a deep-dive on Rippling).

I made this graphic 18 months ago so it’s a little out-of-date, but the crux still holds:

As productivity SaaS has exploded, there have been fewer major companies left to be built; there are only so many broadly-adopted, highly-defensible productivity tools that can ingrain themselves in an organization.

But “the future of work” is broader than the term’s original characterization: the future of work also encompasses how workers prepare for work, find work, and carry out that work.

In that same piece from 2020, I wrote about how I think of work in three stages:

Job Readiness comes first and is about preparing for work. Job Discovery comes next and is about finding a job. Last comes Job Success, which is about doing the job well.

There are still interesting things happening in productivity SaaS (which fits primarily into the Job Success bucket), but the other buckets above are overlooked. Much of the innovation today is happening in job discovery—how we find work—as younger workers rethink the underlying purpose of a career.

This week I’ll focus on that middle bucket, unpacking it in three parts:

1️⃣ Labor Marketplaces & Self-Employment

2️⃣ Digitally-Native Work

3️⃣ Supplementary Income

Let’s dive in.

1️⃣ Labor Marketplaces & Self-Employment

When many people think of “Job Discovery”, they think of LinkedIn. This is especially true for white-collar work. LinkedIn has 700 million users, half of whom are monthly actives.

While most social networks monetize almost entirely through ads (Facebook and Snap both have 99% of their revenue coming from ads), LinkedIn has a more diversified model. LinkedIn makes money in three main ways:

One key thesis I’ve written about in the past is the unbundling of LinkedIn. We’re seeing this both with broad upstarts like Polywork (which you can think of as LinkedIn for Gen Zs, or LinkedIn for more project-based work), and startups building in each of LinkedIn’s key monetization buckets:

This graphic is again 18 months old, and a lot has changed since that piece I wrote in 2020. Jumpstart rebranded to Untapped and now has $83M in funding and 110 employees. Workstream now has $58M in funding and 226 employees, and Contra has $45M in funding and 76 employees. LinkedIn is the 800-pound gorilla in the job marketplace category, and will continue to be picked apart.

We’ve also seen the rise of labor marketplaces. While LinkedIn focuses on the office worker, new companies focus on serving specific verticals (many more blue-collar). Instawork connects hospitality workers to job openings at hotels; Pared connects restaurant workers to restaurants; StyleSeat connects hairstylists to clients.

Some labor marketplaces serve more permanent positions. One example is Incredible Health, which matches nurses with full-time nursing positions. Employers apply to nurses—not the other way around—and compete for the best talent. The market demand is there: the US has a massive nursing shortage, and nursing is projected to be one of the fastest-growing professions over the next few decades.

Other labor marketplaces, including most of those in the graphic above, serve more gig- or project-based work. A hotel might hire a dishwasher through Instawork, for instance, and pay by the hour.

Often the best labor marketplaces offer skilled work that is intermittent and encourages the supply-side (the workers) to return frequently to the marketplace. Workrise, for instance, which was called RigUp when I made the graphic above, connects energy workers to jobs. An oilfield worker or a wind farm worker might use Workrise to find a 3-month gig in Texas. Then after that job is up, they’ll return to Workrise to find the next job. Because they are skilled labor, and because gigs tend to not be permanent, the marketplace enjoys strong retention on the supply side to meet demand. Impact has a similar model for filmmaking, connecting cinematographers and film editors to movies being made.

Workers, meanwhile, have more flexible and autonomous work, choosing when and where to take jobs. A nurse or vet or chef who may have been full-time in a prior life might prefer using a labor marketplace to have more control and agency.

A related shift is the rise of jobs native to the internet.

2️⃣ Digitally-Native Work

Many of today’s job titles wouldn’t have made sense 10 years ago:

Roblox game developer

Discord community manager

TikToker

DAO creator

Webflow builder

Whatnot seller

Metafy gaming coach

Outschool teacher

Rec Room creator

As you can see in the “job title,” many of these forms of work rely on an internet platform. Even in the past year, we’re seeing this list of potential jobs and underlying platforms grow.

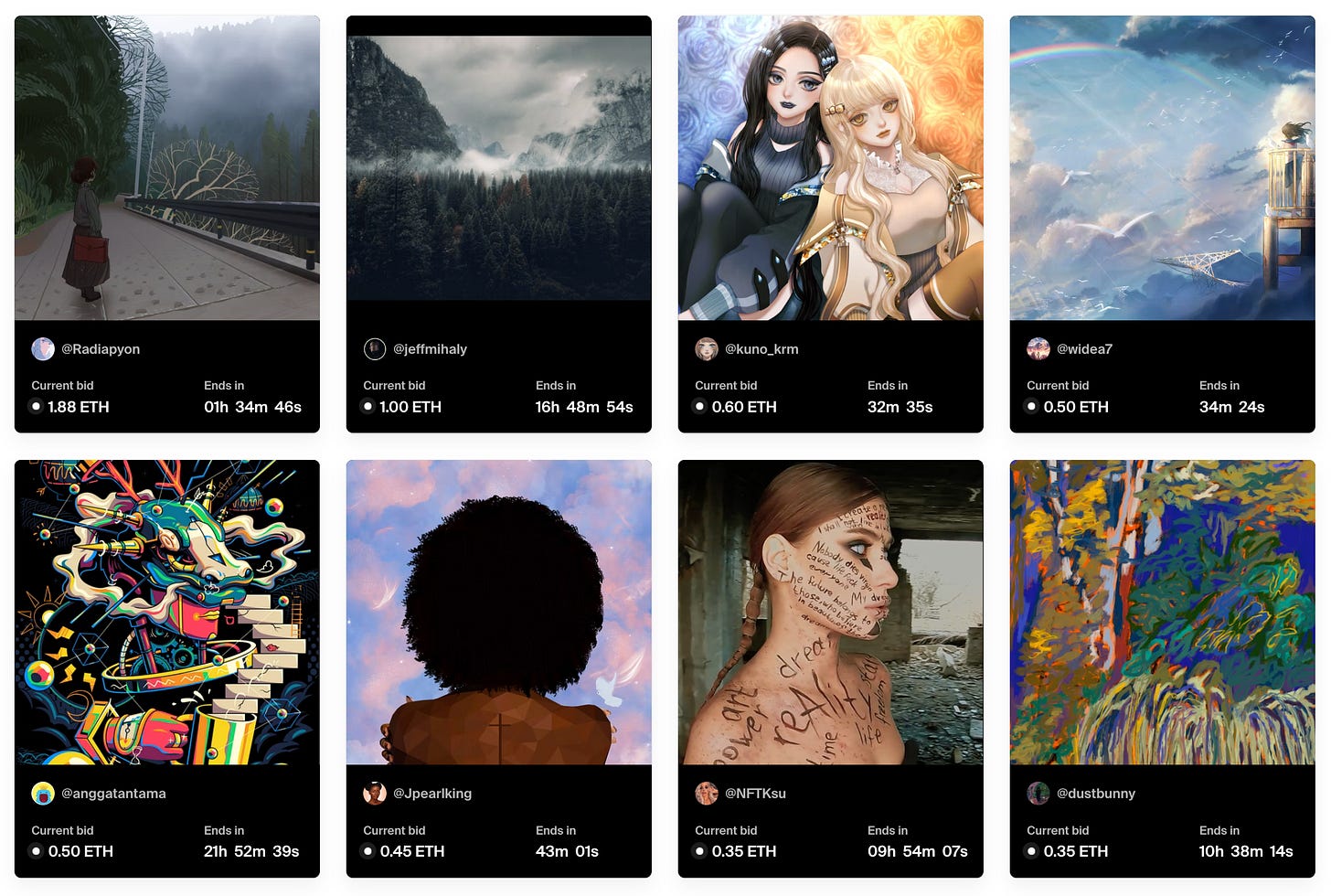

For instance, you can now be a digital artist on Foundation, earning a living selling tokenized art. That opportunity didn’t exist a year or two ago.

Digitally-native jobs have the benefit of being global and scalable. While capital has always been borderless, labor was fixed. Internet platforms facilitate work—and economic opportunity—by making labor borderless.

3️⃣ Supplementary Income

In our modern economy, incomes are primarily single-source. This is especially true for white-collar work. He’s an accountant. She’s a lawyer. You’re a doctor. Our professions become our identities.

The lines between profession and identity have been blurring for centuries. Many of the most common surnames were derived from work: Smith was for blacksmiths, Taylor was for tailors, Webb was for weavers, Ward was for watchmen. You might even be able to guess where the surnames Baker, Cook, and Carpenter come from 🧐

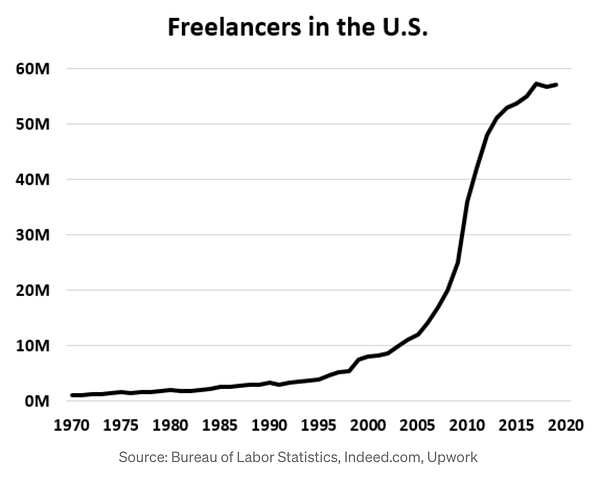

But the tenure of the monolithic career is waning: one recent study found that 70% of Gen Zs have some kind of second job. More than one in three (34%) said their side hustle takes up 20 hours or more each week. Many of these second or third income streams come from the digitally-native jobs mentioned above. The internet’s scalability, zero marginal costs, and global nature enable them.

In 10, 20, 30 years, I expect the average worker’s income to look less like a river and more like a set of tributaries all contributing to a larger body of water. You might work at a startup by day, but run a YouTube channel by night. You might day trade stocks and crypto, while contributing to DAOs and getting paid in tokens. Maybe you do expert network calls on free afternoons, post sponsored content for brands, and manage a paywalled Discord server—all at the same time. Workers will have an arsenal of tools by which to earn a living.

If in 2030 we still derive surnames from work, we might have Mr. Nurse-YouTuber-Writer-Podcaster-GameDeveloper. (Terrible joke, but you get the point.)

Most of these forms of work will be supplementary. Most couldn’t support someone’s living on their own. But that $10K you earn from brand posts on Instagram, or the $20K you made last year doing expert calls with Tegus are a nice cushion: those supplemental income streams make you less reliant on a single employer, encouraging more flexibility and autonomy in how you work.

We’ll also see a rise in passive income, facilitated by new platforms.

Reforge, for instance, taps into the “expert economy.” For everyone 1 teacher or 10 YouTubers, there are 100 (maybe 1,000) knowledge workers with extensive but untapped expertise. These are your engineering directors, your content marketers, your product managers. Reforge taps into that talent pool for educational fontent in a scalable, low-cost way. Experts like Casey Winters (Chief Product Officer at Eventbrite) or Elena Verna (who was SVP, Growth at SurveyMonkey) teach courses on functional expertise. They create the course once, with the help of Reforge’s team, and that course can live online for months or even years, taken by thousands of students. This creates a powerful new source of income for experts, and a way to monetize latent knowledge.

Or take another (very different) example of passive income:

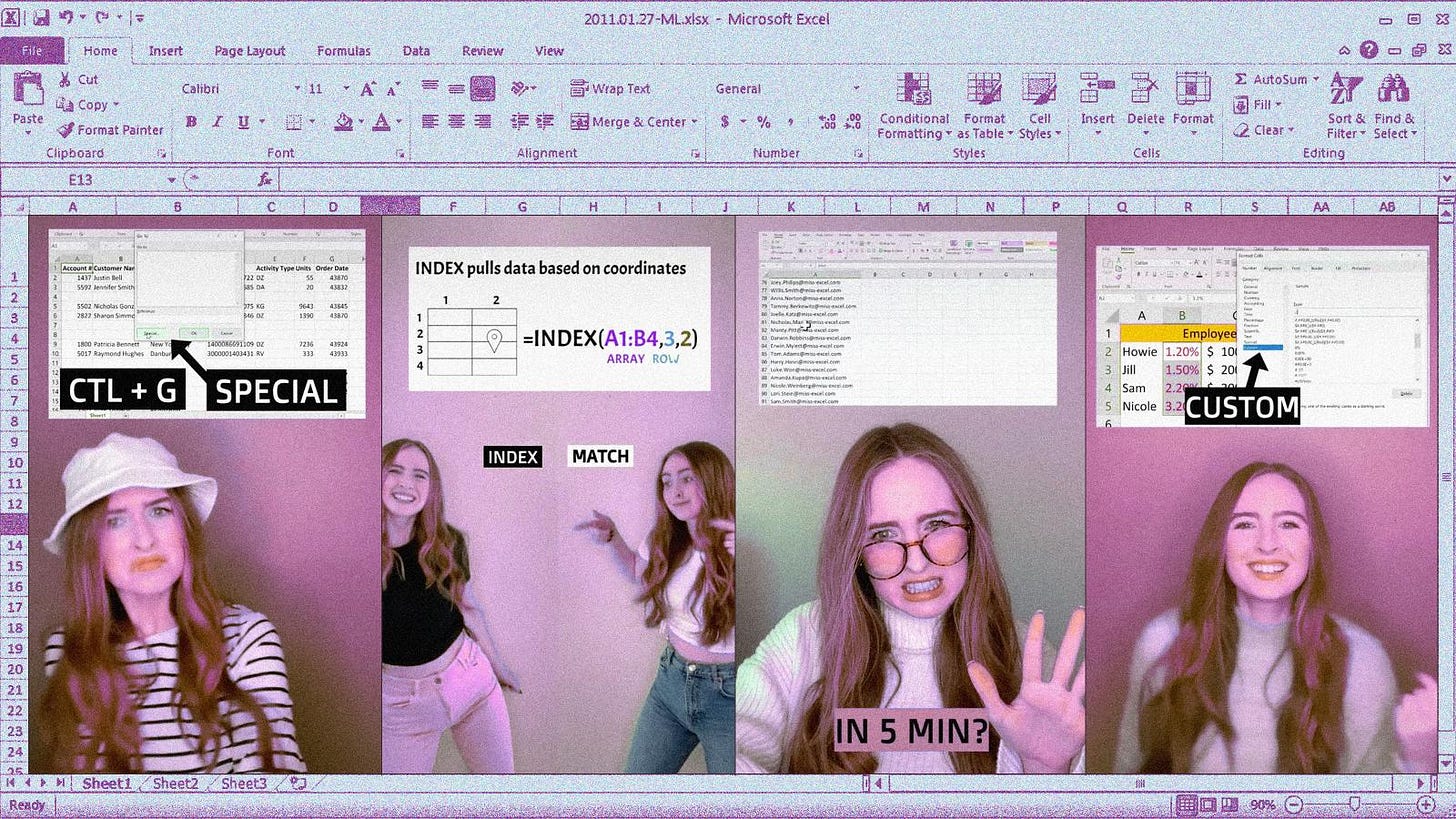

Miss Excel—real name: Kat Norton—has over a million followers on TikTok and Instagram, where she posts content about (you guessed it) Excel. But Norton’s social channels really act as a funnel for her Excel training courses. She earns six figures a day through her courses, all as a one-woman business.

Miss Excel has two “new” digitally-native job titles—TikToker and “Excel course creator”—that didn’t really exist a few years ago. And her income is largely passive: she’s often traveling the world, working just a few hours a week to make content, while her evergreen Excel course flies off the proverbial shelves.

Final Thoughts

There’s an exchange you hear often among Gen Zs—in TikTok comments, on Twitch streams, in subreddits.

Someone will ask, “What’s your dream job?” And a young person will respond, “I don’t dream of labor.”

It’s a funny and snarky comeback, but it also captures a new generation’s sentiment towards work. Perhaps the biggest change happening in work is behavioral—a massive, decades-long cultural rethinking of why we work and how we work. Gen Zs trade Millennial idealism for Gen Z pragmatism. The workaholic heroes from Millennial pop culture—Leslie Knope from Parks & Rec, Anne Hathway’s character in The Devil Wears Prada—are no longer glorified, but pitied.

We see this in the new normal: more flexible, self-directed, remote work. A study last week from the ADP Research Institute found that 71% of workers age 18 to 24 would quite if employers said they had to come back into the office full-time.

And we see this behavior change in movements like the antiwork movement. One of the best pieces I’ve read in recent months is Anna Codrea-Rado’s long Vice piece called Inside the Online Movement to End Work. The journalist goes deep into r/antiwork, which has become one of Reddit’s most popular subreddits. The antiwork subreddit describes itself as “a subreddit for those who want to end work, are curious about ending work, and want to get the most out of a work-free life.” r/antiwork now has 1.7 million members (who fittingly call themselves “Idlers”), up from just 13,000 in 2019. Comically, the subreddit has over twice as many members as r/careerguidance.

Our modern concept of work is relatively new—only about 300 years old. For most of human history—from the Greeks, to the Romans, to the Middle Ages—leisure was the basis of culture. Only in the 16th century, when the Reformation brought the rise of the Protestant work ethic, did people begin to see work as a way to bring oneself closer to God. The religious aspect of work faded, but faith in hard work persisted, evolving into the modern-day spirit of capitalism.

The shift happening right now in work might be a return to the way things used to be—when work wasn’t the center of society. Younger workers place work differently in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Where an older cohort placed work at the top—self-actualization—younger workers place work at the bottom, fulfilling basic needs like food and shelter.

They don’t live to work; they work to live.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: