Everything Everywhere All At Once: The Explosion in Generative AI

Examining Image Models, Language Models, and Use Cases for Generative AI

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Everything Everywhere All At Once: The Explosion in Generative AI

The movie Everything Everywhere All At Once is one of the more…chaotic movies in recent memory. The film tells the story of Evelyn (Michelle Yeoh), a Chinese immigrant who runs a laundromat that’s being audited by the IRS. Evelyn soon discovers that she lives in but one universe out of infinite universes, and she must traverse the multiverse in order to save her family.

In many ways, the film acts as a metaphor for the chaos of the internet. In an interview with Slashfilm, Daniel Scheinert, one of the film’s directors, put it this way: “We wanted the maximalism of the movie to connect with what it’s like to scroll through an infinite amount of stuff.”

The YouTuber Thomas Flight (who has an excellent analysis of the film) calls Everything Everywhere one of the first “post-internet” films, capturing the weirdness of online life. One of the fascinating aspects of living in 2022—and one of the guiding themes for Digital Native—is the fact that our brains are no different than they were a century ago (evolution, it turns out, takes a long time), yet our world has changed dramatically in 100 years. As Flight puts it: “We live in a time when more interesting ideas, concepts, people, and places can fly by in the space of one 30 minute TikTok binge than our ancestors experienced in the entirety of their localized illiterate lives.” How does that rapidly-evolving digital chaos warp our slow-to-evolve human minds?

The universes of Everything Everywhere are diverse and deeply, deeply weird. There’s a universe with no human life, in which everyone is a motionless rock. There’s a universe in which everyone is a crayon drawing. There’s a universe in which everyone has hot dogs for fingers (I told you it’s weird).

The movie captures the internet’s kinetic energy and relentless pace.

Yet the movie reminded me less of the internet, and more of what’s happening in generative AI. Just as the film allows its protagonist to translate anything from her imagination into a tangible reality, generative AI allows us to turn our thoughts into words and images and videos.

Here’s what Midjourney gives me when I type in the prompt “A person made entirely of fruit”:

Here’s what I get when I type “New York City skyline in the style of Van Gogh”:

I could spend hours (and I have spent hours) experimenting with such prompts.

Generative AI—which broke through in 2022—is the most exciting technology since the rise of mobile and cloud over a decade ago. In last fall’s The TikTokization of Everything, I wrote about how mobile and cloud have been the two engines powering tech for 10+ years:

Mobile facilitated the rise of massive consumer internet companies: Uber and Lyft, Instagram and Snap, Robinhood and Coinbase. Each was founded between 2009 and 2013. Digital advertising rapidly shifted to mobile in the 2010s, and desktop-era companies like Facebook had to scramble to reinvent their businesses.

Cloud, for its part, underpinned an explosion in software-as-a-service (SaaS) and enabled data to become the most prized resource in a business (“Data is the new oil” and all that). Emergent companies—again, each founded between 2009 and 2013—included Slack and Airtable, Stripe and Plaid, Snowflake and Databricks.

Over the past few years, we’ve seen a lot of clamoring for what comes next. Virtual reality? Augmented reality? Autonomous vehicles? Crypto? Web3? Each is promising for unique reasons and within distinct use cases, but each is very, very early.

Yet generative AI is at an inflection point (more on that later) and is underpinning a Cambrian explosion in innovation. The years 2009 to 2013 birthed dozens of transformative startups powered by mobile and cloud. The coming years will do the same, with generative AI this time acting as the catalyst.

Over the holiday, a friend asked me a question: is AI a bubble, or the next big thing? The answer is probably both. There’s a lot of excitement right now, much of it warranted and much of it probably irrational, premature, or both. But when you zoom out, there’s no doubt that we’re on the cusp an exciting new era of technology.

This week’s piece unpacks what’s happening in generative AI as we enter 2023. We’ll look at:

Image Models

Language Models

Use Cases and Business Models for Generative AI

The goal here is to understand the “why now” behind what’s happening, and to explore the ways that startups can build in the generative AI space.

Let’s jump in.

Image Models

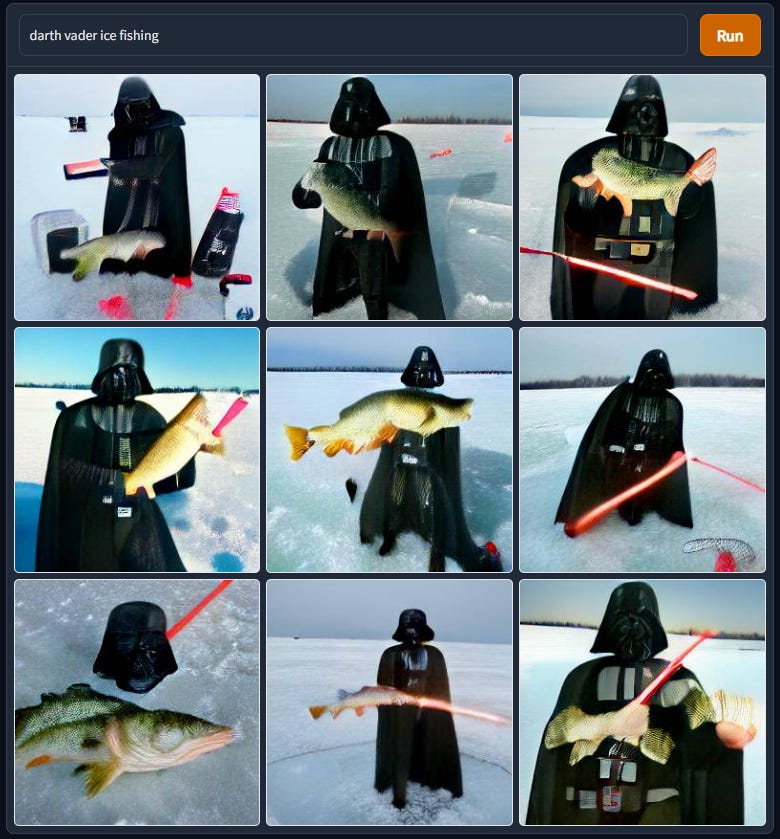

Text-to-image generative AI exploded in 2022. First on the scene was DALL-E from OpenAI (the name is a portmanteau of the artist Salvador Dalí and Pixar’s WALL-E). Not everyone could access DALL-E, but creations began to make their way across the internet; my favorite is the Twitter account Weird DALL-E Generations.

After DALL-E got things started, Stable Diffusion and Midjourney came along last summer and shook things up. Stable Diffusion was groundbreaking in that it was open-source, meaning developers could build on top of it. To get technical, Stable Diffusion moved diffusion from the pixel space to the latent space, driving a profound increase in quality. (More on that here if you’re interested.) Midjourney was groundbreaking in how accessible it was. Midjourney exists on Discord: anyone can sign up for a free account and get 25 credits, with images generated in a public server. (You can join the Discord here.) After you exhaust your 25 credits, you pay either $10 or $30 a month, depending on the number of images you want to create and whether or not you want them to be private to you. Midjourney has rapidly become one of the most popular servers on Discord (perhaps the most popular server?) with 7.4 million members. (I believe that the Genshin Impact server, with ~1M members, previously held the crown as top server, but I could be wrong on that.)

You can see here how Midjourney, DALL-E 2, and Stable Diffusion each have slightly different styles when using the same text prompt:

This timeline, meanwhile, gives a broader appreciation of how AI image generation has improved over the past decade (notice both the growing complexity of the prompts in recent years, and the improving fidelity of the outputs):

Last year was a tipping point for image models, with rapid improvements in quality. One example: famously, AI is bad at making hands. It’s very difficult to know how many fingers have already been made unless the AI has an excellent sense of context. The result is that we end up with lots of four- and six-fingered hands. In the below side-by-side of Midjourney v3 (July 2022) and Midjourney v4 (November 2022), you see marked improvements: we no longer have a penguin with two beaks and a penguin with three legs.

When I think of the early challenges of image generation, I think back to the early challenges of animation a century ago. One of the reasons that Mickey Mouse wears gloves is that it made for much faster animation; hands are difficult to draw. The same goes for Fred Flintstone and George Jetson—neither has a visible neck, because allowing for a neck meant that a character’s entire body needed to shift with each movement and expression. That meant a lot more work for an animator. A necktie and a high collar offered tricks for animators to speed up production.

Half a century later, of course, animation has come a long way. Finding Nemo was in some ways an excuse for Pixar to show that it could animate realistic water. Pixar waited until The Incredibles, its 6th feature film, to tell its first story about humans because CGI technology hadn’t previously been ready (part of the reason Toy Story focused on toys was because Pixar couldn’t yet render detailed humans—you barely see Andy and his mom in the film).

The arc of digital creation is following a similar path to the arc of animation, and the pace of improvement in technology is only increasing. The difference between the Midjourney images of penguins above, for example, was the result of just a handful of months.

Language Models

In the Black Mirror episode “Be Right Back”, a husband and wife move into a new home together. The next day, the husband is killed in a car accident. His widow learns of a new service that lets you chat with your deceased lover; the tool digests text messages and social media history to learn how your partner would have responded, and then chats with you in his place. The plot of this episode (which came out in 2013) is now reality. A startup called HereAfter.ai lets you chat with an interactive avatar of a deceased relative, trained on that person’s personal data.

Last year saw a leap forward in language models alongside the leap forward in image models. In November, OpenAI released ChatGPT, which gained 1 million users in the first five days after release. ChatGPT is incredible; using it is a “magic moment” in technology akin to your first time using Google Search. (Every time I use ChatGPT, I’m reminded of the Arthur C. Clarke quote: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”)

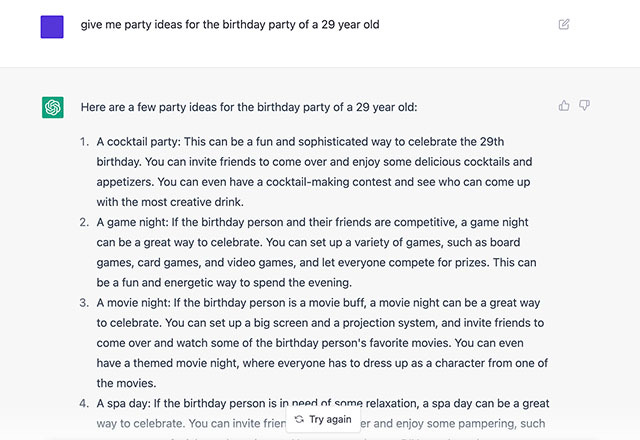

A few examples below of what ChatGPT can do:

Prompt: “What are wormholes? Explain like I am 5.”

Prompt: “Give me party ideas for the birthday of a 29-year-old.”

Prompt: “Write a song on working from home with accompanying chords.”

While GPT-3 came out less than three years ago with ~200 billion parameters, the new GPT-4 has ~1,000,000,000,000 (a trillion) parameters.

The size of models is growing exponentially, and each new model makes leaps forward in its ability to come up with new ideas, understand context, and recall information. Larger models are also much, much more expensive to train. Training a model with hundreds of billions of parameters can cost millions of dollars. For this reason, big models are becoming the foundations upon which startups build. My colleague Erin Price-Wright draws the analogy to Amazon’s AWS or Microsoft’s Azure—cloud computing platforms upon which millions of businesses rely.

As an example, many startups build on OpenAI’s GPT-3. Jasper, for instance, provides an AI copywriter powered by GPT-3. Starting at $29 / month / seat, Jasper gives you writing superpowers. Yet Jasper was taken aback by OpenAI’s release of the free ChatGPT, which it worried would cannibalize its business. (The Information has some terrific reporting on the Jasper-OpenAI relationship.) The dynamic between foundational models and the companies building on them will be interesting to watch play out this year.

Use Cases of Generative AI

One of the earliest forms of AI was handwriting recognition, used primarily by the postal service to read addresses on envelopes. But that use case of AI is incredibly specific. When it comes to generative AI, we’ve seen: 1) massive improvements in image and language models, and 2) valuable infrastructure provided by companies like OpenAI, Hugging Face, and Stability.ai. Those two factors combine to broaden the possibilities of use cases.

One dramatic oversimplification is that use cases can be grouped into two buckets: 1) Creativity, and 2) Productivity.

When it comes to creativity, we see generative AI lowering barriers to creation. With Midjourney, you can make concept art for a movie. Companies like Latitude.ai create games like AI Dungeon that leverage GPT-3 for AI-powered exploration. Alpaca, meanwhile, took Twitter by storm with its demo of its Photoshop plug-in; the company’s mission is “to combine AI image generation power with human skill.”

I’ve written in the past about the growing accessibility of creative tooling. Back in 2015, Steven Johnson wrote in The New York Times:

The cost of consuming culture may have declined, though not as much as we feared. But the cost of producing it has dropped far more drastically. Authors are writing and publishing novels to a global audience without ever requiring the service of a printing press or an international distributor. For indie filmmakers, a helicopter aerial shot that could cost tens of thousands of dollars a few years ago can now be filmed with a GoPro and a drone for under $1,000; some directors are shooting entire HD-quality films on their iPhones. Apple’s editing software, Final Cut Pro X, costs $299 and has been used to edit Oscar-winning films. A musician running software from Native Instruments can recreate, with astonishing fidelity, the sound of a Steinway grand piano played in a Vienna concert hall, or hundreds of different guitar-amplifier sounds, or the Mellotron proto-synthesizer that the Beatles used on ‘‘Strawberry Fields Forever.’’ These sounds could have cost millions to assemble 15 years ago; today, you can have all of them for a few thousand dollars.

This is remarkable. And it continues to hold true: Parasite, the 2020 Best Picture winner, was cut on Final Cut Pro. Tools progressively get more affordable and more accessible, crowding in more creation.

AI broadens what’s possible. Imagine Roblox Studio powered by AI, or what AI can unlock when combined with Figma. It’s now been over two years since I made this graphic:

YouTube was revolutionary, but left barriers to creation: 1) the money to invest in expensive tools, and 2) the knowledge of how to use those tools. TikTok removed those barriers with no-code-like tools, leveling the playing field. The result is that 1 in ~1,000 people on YouTube create content, while closer to 60% of TikTok users create.

Perhaps this year, this graphic can be updated with a third box—an intuitive, powerful tool that goes beyond no-code creation tools and leverages generative AI in the process of making content. Dream up photos for Instagram, videos for TikTok, or content for a de novo social network.

Just as AI amplifies creativity, AI amplifies productivity. We see this in many of the tools that give writers and marketers superpowers, like Jasper.ai, Copy.ai, and Lex. We see this in Gong, which uses AI to help B2B sales teams be more efficient and effective. We see this in GitHub Copilot, which turns natural language prompts into coding suggestions across dozens of programming languages, and which became generally available to all developers in June 2022.

The early targets of AI (particularly built on language models) will be rote, repetitive tasks. One area I see ripe for reinvention: customer support. These are the areas where today’s AI can already make serious inroads. More complex tasks (3D game creation comes to mind) will come further down the road.

One final thought on use cases: personalization. Personalization warrants a dedicated piece in itself (perhaps that will come later this month), but I like how my friend Alex puts it:

Now, what business models will startups turn to?

What business models will be most valuable?

Software-as-a-Service is a beautiful thing. Predictable, recurring revenue. 80%+ gross margins. Ideally net dollar retention >100%, meaning that even without acquiring any customers, your business steadily grows year-over-year. (140% NDR implies that with zero new customers, you will grow revenue 40% YoY).

My hunch is that many of the best AI startups will be SaaS companies. Why change such a good business model?

Runway, for example, is one of the most exciting AI companies out there. Runway offers an AI-powered creation suite, and seeing a product demo is jaw-dropping. You can get a sense for some of the product’s magic from videos like this one:

In that video, Runway offers text-to-video generation, conjuring up a city street and then letting the user quickly make changes (e.g., remove a lamp post, or make the video black and white). Imagine you work in special effects in Hollywood—Runway lets you add an enormous explosion in seconds, something that would take tremendous time and money sans AI. CBS is a customer, using Runway to cut its editing time on The Late Show from five hours to five minutes. New Balance is a customer, using custom Generative Models on Runway to design their next generation of athletic shoes.

Runway pricing will look familiar to any SaaS enthusiast:

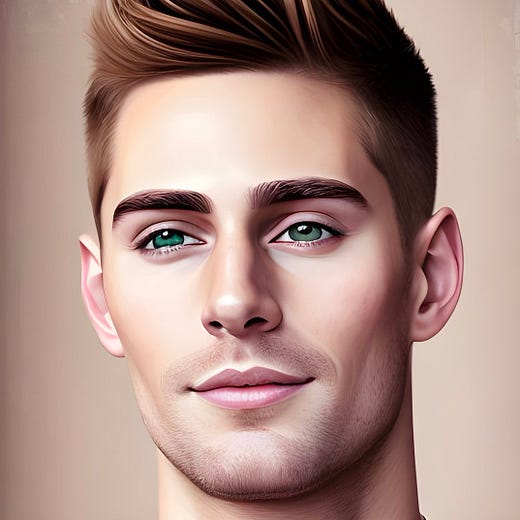

We’re also seeing AI companies turn to other familiar business models. Midjourney leans on consumer subscription. Lensa, which took the world by storm in December, offers freemium pricing + micropayments. It cost me $8.99 for a 50-pack of custom avatars. (Side note: Lensa is a classic example of a product tapping into people’s vanity, and harks back to last year’s Digital Native piece The Seven Deadly Sins of Consumer Technology.)

The challenge with Lensa, of course, is defensibility; Lensa lives on top of Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok and will have to figure out how to develop a moat. (The same issue may apply to SaaS companies building on foundational models, as we saw earlier with Jasper vs. ChatGPT.)

One creative new company, building with a familiar business model, is PromptBase. PromptBase is a marketplace for generative AI prompts. It’s surprisingly difficult to come up with the right prompt to produce a beautiful piece of AI art. Prompts sold on PromptBase are often long, detailed, and highly-specific. The marketplace has 11,000 users so far.

The short answer for business models in generative AI is that we’ll likely see the same go-to business models that have powered tech (and business writ large) over the last generation. There will be ad-driven social networks, micropayment-driven MMOs, usage-based pricing. Marketplaces will likely (again) prove to be more capital intensive to scale, but will (again) have powerful network effects that provide strong moats. And SaaS will (again) prove to be among the most desirable business models, though AI SaaS companies will need best-in-class products to cut through the noise of how crowded enterprise SaaS has become.

Final Thoughts

When a technology changes how a broad range of goods or services are produced, it’s called a “general-purpose technology.” There have been two major general-purpose technologies for humans: 1) the Agricultural Revolution, which gave us food production at scale and let us transition from hunting and gathering to farming; and 2) the Industrial Revolution, which gave us manufacturing at scale. The folks at Our World in Data argue that Transformative AI marks a third:

This is an exciting moment. Overhyped? Perhaps a little. But that hype will also help attract the talent that will push forward the field; in some ways, it’s self-fulfilling. And there are of course ethical issues to work out—leaps forward in technology often walk a fine line between deeply-impactful and dystopian.

I’ve used this quote from Midjourney’s David Holz before, but I like how it frames the moment:

We don’t think it’s really about art or making deepfakes, but—how do we expand the imaginative powers of the human species? And what does that mean? What does it mean when computers are better at visual imagination than 99 percent of humans? That doesn’t mean we will stop imagining. Cars are faster than humans, but that doesn’t mean we stopped walking. When we’re moving huge amounts of stuff over huge distances, we need engines, whether that’s airplanes or boats or cars. And we see this technology as an engine for the imagination. So it’s a very positive and humanistic thing.

An engine for the imagination.

I’m sure I’ve made glaring oversights in this piece, and I’d love to hear them. I’d also love to be challenged on which use cases and business models will come first and which will ultimately be most valuable. Shoot me an email or find me on Twitter (@rex_woodbury).

One exciting thought to end on: generative AI will soon collide with other exciting technologies, such as VR and AR. Imagine text prompts that generate immersive, three-dimensional virtual worlds. That will likely be a possibility before too long. Technology often moves quickly: within a single lifetime (63 years) we went from the Wright Brothers’ first flight (1903) to putting a man on the moon (1969), 239,000 miles from Earth. Within the lifetime of someone being born today, we’ll see every part of human life, work, and society reinvented by AI.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Terror of Everything Everywhere All At Once | Thomas Flight

Money Will Kill ChatGPT’s Magic | David Karpf, The Atlantic

The Best Little Unicorn in Texas: Jasper AI and ChatGPT | Arielle Pardes, The Information

AI’s Impact | Our World in Data

Jeremiah Lowin and Patrick O’Shaughnessy (podcast)

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: