From Chalkboards to Chatbots: Our Long-Awaited Education Revolution

Innovation in Edutainment, Reskilling, and Personalized Learning

Weekly writing about how technology shapes humanity, and vice versa. If you haven’t subscribed, join 40,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

From Chalkboards to Chatbots: Our Long-Awaited Education Revolution

How many industries are roughly the same in 2023 as they were in 1923?

Or, for that matter, as they were in 1823? Not many. But one industry stands out—education. And it’s a big one, worth $1.6 trillion in the US and $4.7 trillion globally. For reference, that makes the US education market 5.3x bigger than the US advertising market, which supports tech companies like Google, Facebook, Pinterest, Snap, and Twitter. There’s clearly a lot of value to capture, but that value gets lost in a mess of incentives, red tape, and bureaucracy.

The first American public high school was established in Massachusetts in 1821. Fast forward 200 years, and our education system looks mostly the same. We lump education into the first ~20 years of life, we stick by analog teaching methods, and we fail to refresh curriculums for our modern world (35 states don’t teach any personal finance, but all 50 states learn that mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell). Today’s kids learn in much the same way that 1821’s kids learned—a time when Napoleon and Thomas Jefferson were still alive, and when Thomas Edison’s invention of the lightbulb was still 60 years away.

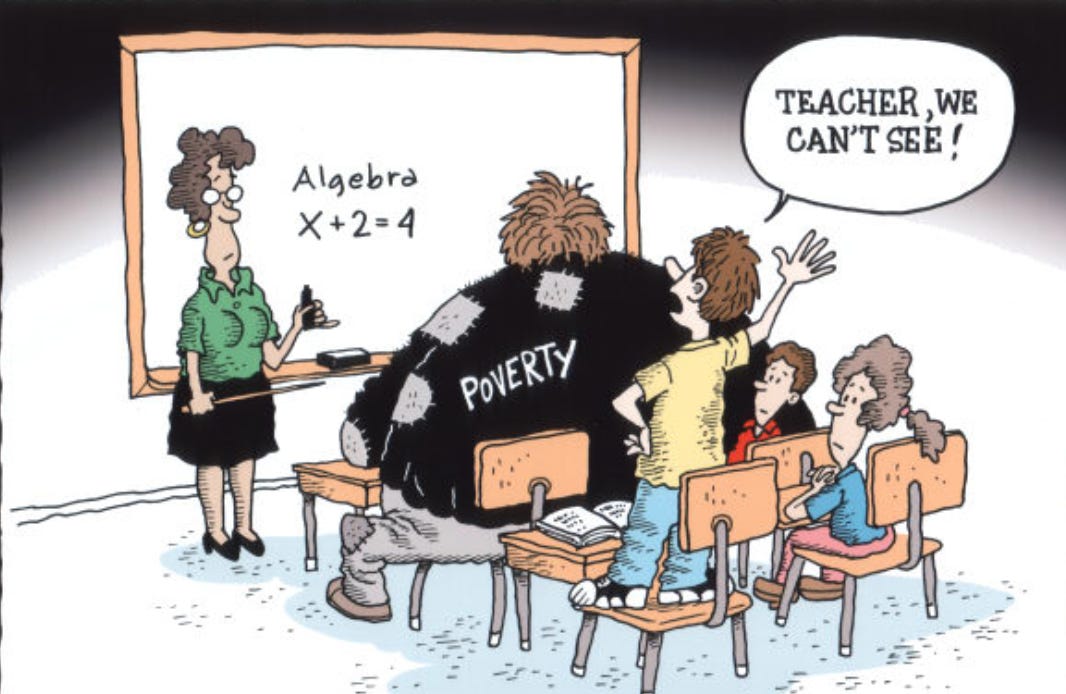

I’ve always had a love for education. Education is a tangible and emotional industry; you can see the moment a learner “lights up” with understanding and masters a concept or a task. And education is directly tied to economic opportunity and economic mobility, but has historically been gated by access. The promise of technology, of course, is to broaden access—and technology should make good educations accessible to more people.

So why has EdTech stagnated? Why is “EdTech” a bad word in many venture circles?

Many education business models are subject to thin Learning & Development (L&D) budgets at enterprises and many education startups have to sell into lethargic school systems. But there are compelling business models and go-to-markets in education (more on that later), and we’re at a breaking point where things need to change: the pace of technological advancement is accelerating, and our education system is still designed for an Industrial Revolution-era world.

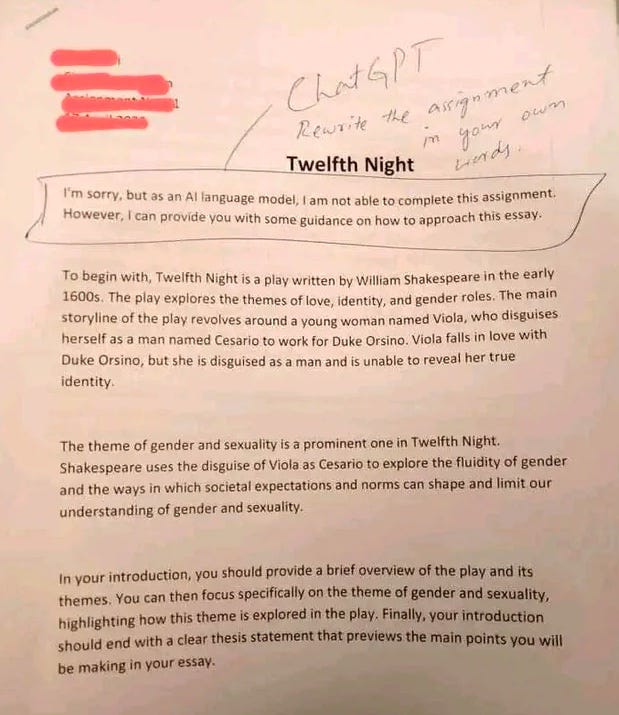

AI is set to both automate jobs (requiring us to retrain workers—fast) and to reinvent education delivery—even if kids are still figuring out how to get away with using ChatGPT:

I’m not bullish on the American education system changing; it’s too bureaucratic, too regulated, too slow-moving. But I am bullish on a new class of entrepreneurs building new products that change how we learn and how we prepare people for the workforce.

Below are three areas ripe for innovation: edutainment, the blending of education and entertainment; reskilling and upskilling; and skill-based learning outside of the university system. We’ll also dig into what business models will prevail and why AI might (finally) deliver the holy grail of education: personalized learning.

Education 🤝 Entertainment

There’s a quote by the philosopher Marshall McLuhan that I’ve always liked:

“Anyone who tries to make a distinction between education and entertainment doesn’t know the first thing about either.”

The problem with our education system is that it tries to make this distinction; it doesn’t appreciate the overlap of education and entertainment. For effective learning, the two need to co-exist.

Entertainment has historically followed a reliable march toward rich media formats. We saw this offline with books → movies and television → video games. We saw it online with Twitter (text) → Instagram (photos) → TikTok (video) → Fortnite (immersive virtual worlds).

Education should follow a similar progression. Too many classrooms are stuck in the textbook era, making poor use of technology for immersive learning experiences. I expect the next generation of education products to lean into richer content formats.

Because of barriers to adoption in schools (more on that later), innovation has mostly happened outside the school system. Consumer-facing applications have pushed education forward over the past 15 years.

YouTube, in many ways, is the world’s largest education company: 2.7 billion people use YouTube each month, 52% of global internet users; 86% say they regularly use YouTube to learn new things. Every day, we watch 5 billion distinct videos and consume 1 billion hours of video. Every minute, people upload 400 hours of video to YouTube.

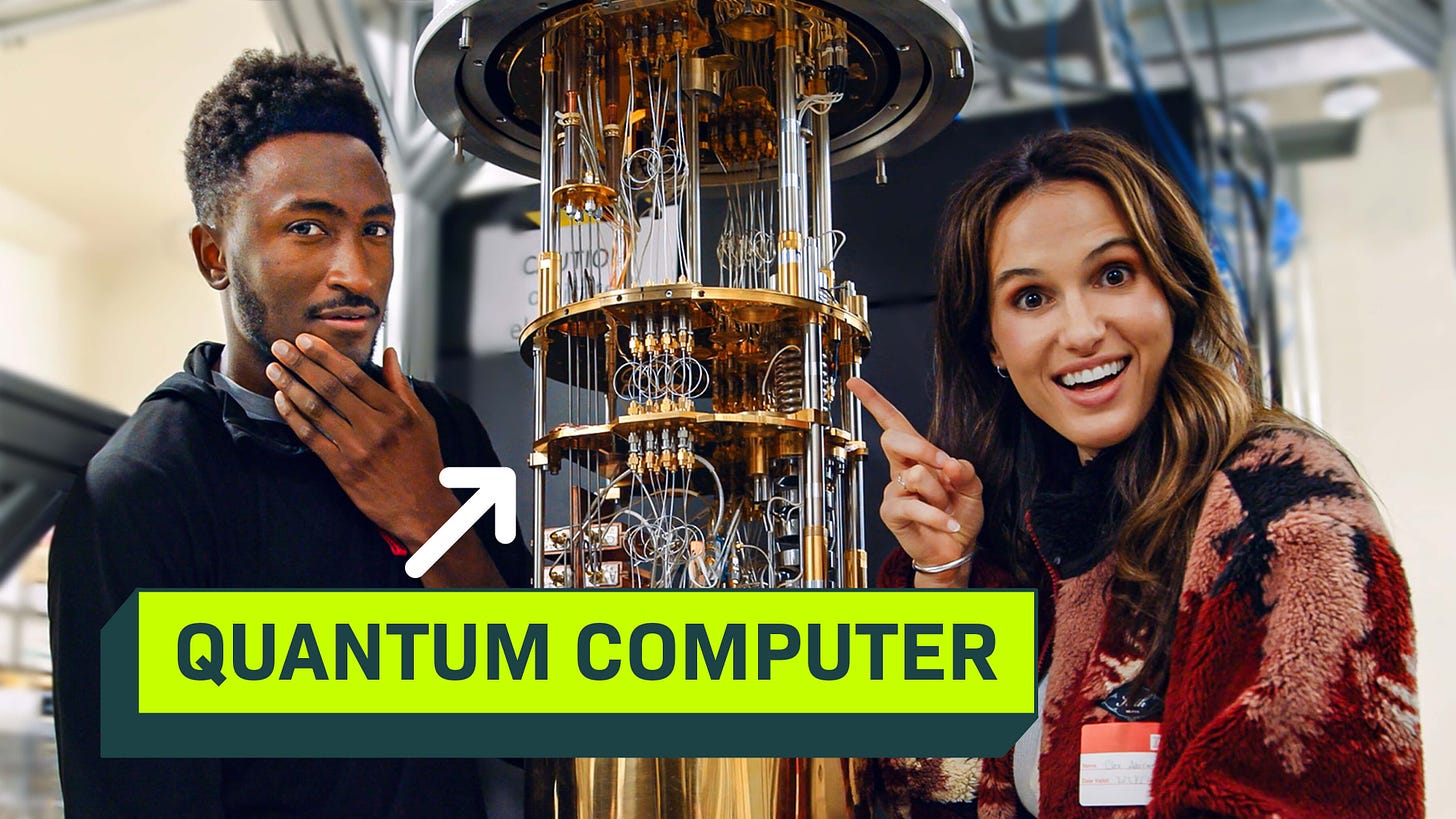

There’s a whole class of “edutainment” creators on YouTube—creators who specialize in making engaging content to teach the viewer about something. One example: one of my closest friends, Cleo Abram, makes technology explainer videos covering everything from Formula 1 racing to nuclear fusion. Her latest video is a collaboration with MKBHD explaining how quantum computers work:

How many young people cultivate an interest in science because of creators like Cleo?

In many ways, YouTubers are this generation’s Bill Nye the Science Guy (the OG edutainment creator)—only at a far greater scale and at a much more accessible price-point. Billions of people around the world can learn nearly anything on a free, ad-supported website.

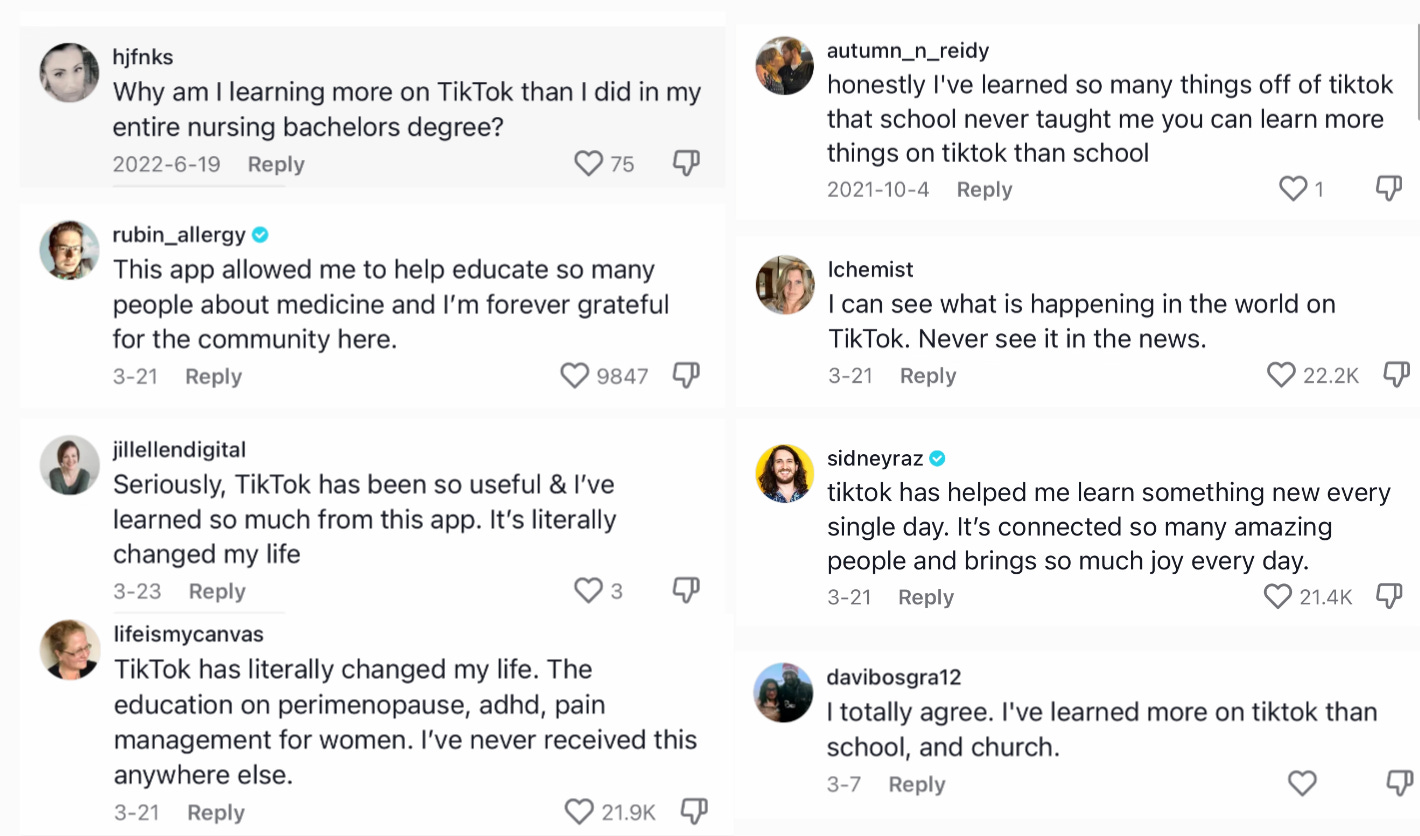

TikTok is following in YouTube’s footsteps. When the government was threatening to ban TikTok, a common refrain on the app was, “I’ve learned more on TikTok than I ever did in school.” A few of the comments I saw:

(Side note: I have a friend who found herself referencing TikTok learnings so often that she now won’t say “I saw on TikTok…” and will instead say “I read in The New York Times…”)

Last month, TikTok even added a STEM tab—Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics—to its homepage. (Conveniently, and not coincidentally, this addition coincided with TikTok’s appearance before Congress.) Education-focused versions of TikTok have also popped up in the startup world: Revyze in Europe, for instance, or Zigazoo for kids.

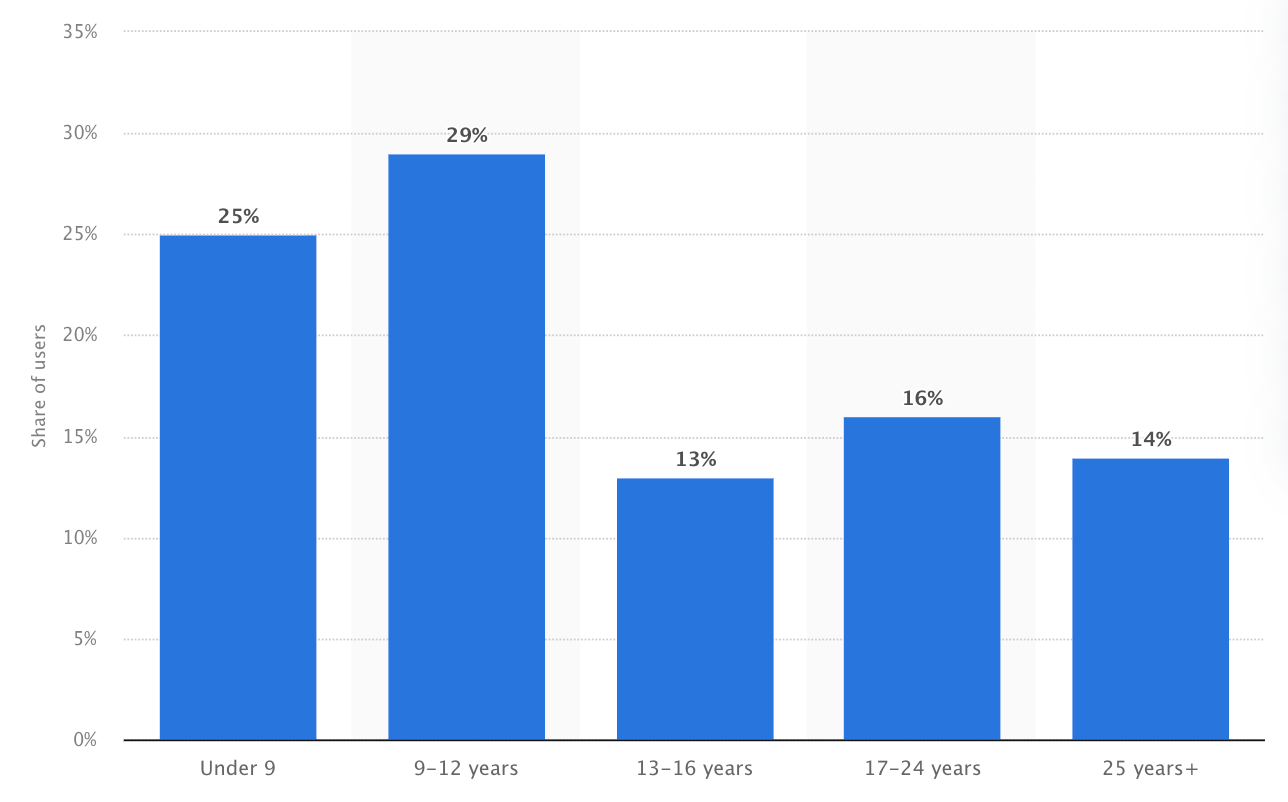

Roblox and Minecraft—even more immersive forms of entertainment than YouTube and TikTok—are also edutainment companies. Roblox users spend a lot of time in Roblox: a recent Qustodio study made headlines for showing how TikTok is running circles around YouTube in daily engagement (113 minutes per day vs. 77 minutes per day, for daily actives), but Roblox trumps them both at a staggering 190 minutes per day, up 90% since 2020.

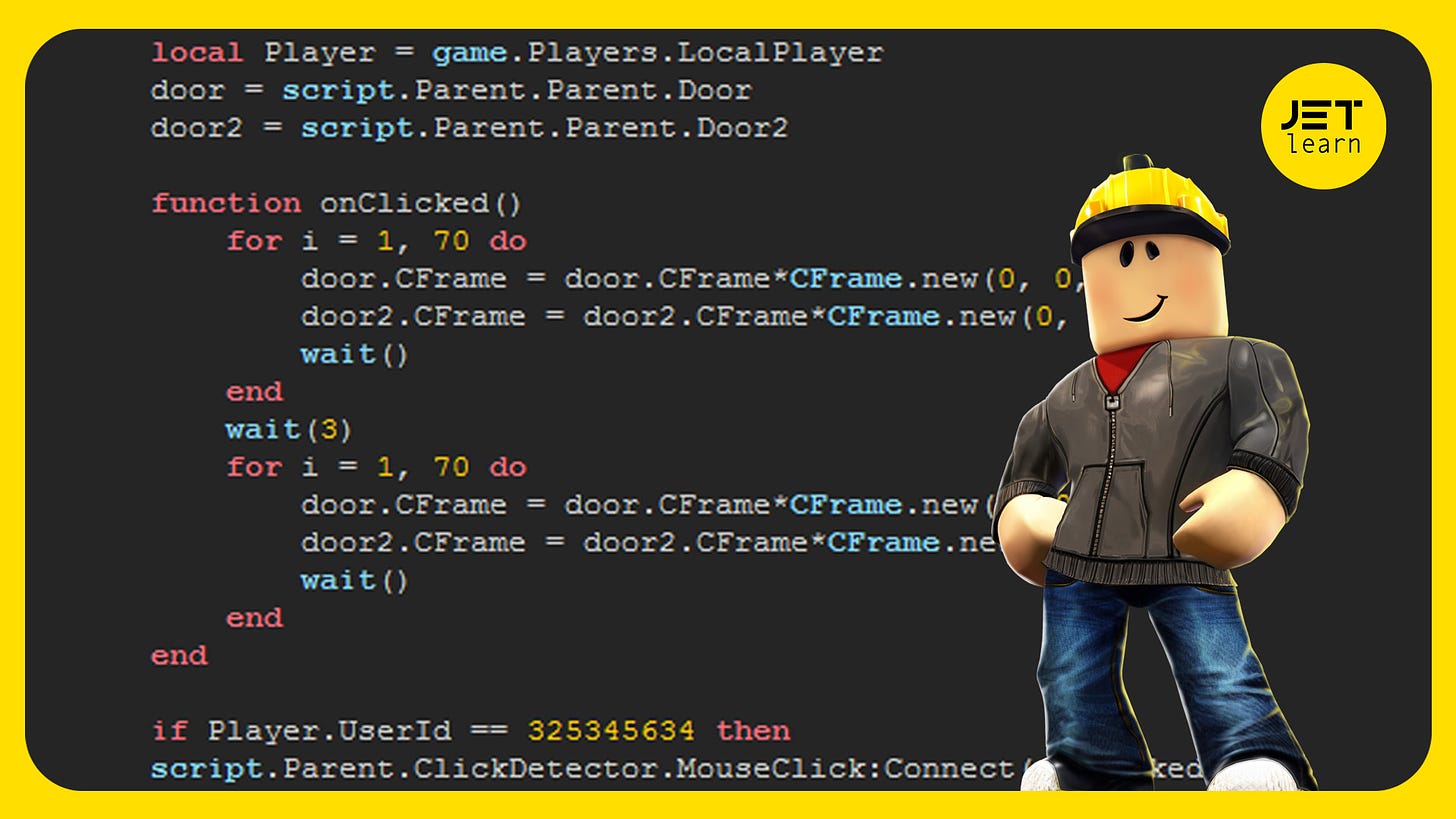

Roblox Studio uses the scripting language Lua, and thousands of teens and pre-teens have learned Lua in order to build Roblox experiences.

Because Roblox users skew young—about 50% are 12 or under—Lua development is often the first technical education that many young people receive.

Minecraft is similarly educational. For many years, “Minecraft” was the second-most-searched term on YouTube behind “music” as users clamored to learn how to build in Minecraft. In one Times profile of Minecraft players, a seventh-grader named Gus types a command to give himself a better weapon: “/give AdventureNerd bow 1 0 {Unbreakable:1,ench:[{id:51,lvl:1}],display:{Name:“Destiny”}}.” That command gives a bow-and-arrow weapon to AdventureNerd, his avatar; makes the bow unbreakable; endows it with magic; and names the weapon Destiny.

Gaming is the most popular category in entertainment: 40% of Millennials (~30M Americans) report spending over 22 hours a week gaming—3+ hours per day. This makes gaming an interesting method of delivery for educational content. And there are still ample opportunities for entrepreneurs. Specifically, I see an opening for a edutainment-oriented MMO that combines the ease of building in Minecraft with the platform capabilities of Roblox, all in a browser-based virtual world that’s more accessible and viral (a hyperlink is the best unit of viral distribution ever created).

Next-generation games can also incorporate AI to personalize the playing and learning experience for each user. DreamBox Learning, which sells into schools, offers math games that adapt to each learner’s strengths and weaknesses. Every learner will get a tailor-made set of math lessons. This concept should extend to online MMOs that incorporate educational elements; the rapid improvement of LLMs should turbocharge personalization.

It’s also inevitable that we progress to more immersive formats—augmented reality and virtual reality. These fields are still early in education, though there are promising players. PrismsVR, for instance, uses virtual reality to better teach math. Available on MetaQuest, Prisms offers students experiential learning in 3D modules aimed at teaching abstract concepts like algebra and geometry.

Edutainment should follow a progression to more 3D worlds and virtual reality, incorporating game-like elements to help young people learn in engaging ways.

Reskilling & Upskilling

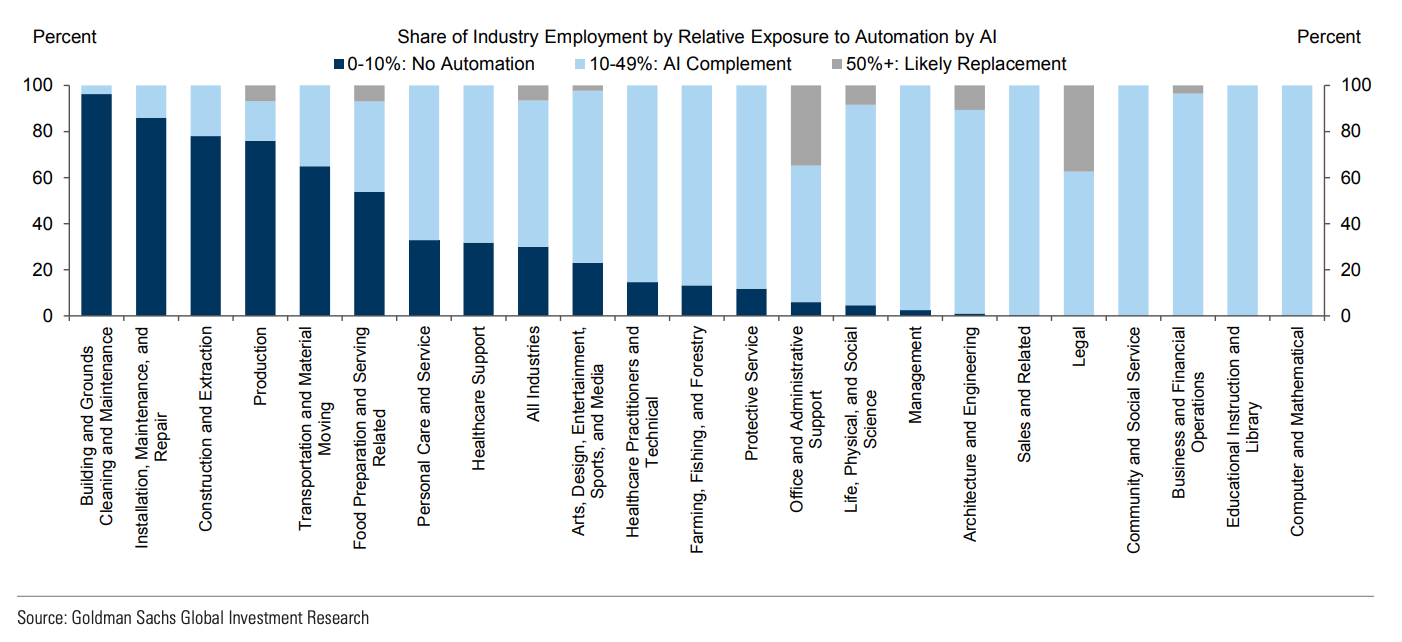

In The AI State of the Union, I wrote about how AI will automate jobs. The takeaway: we’re in for a seismic shift in our labor markets. A report by Goldman Sachs estimates that AI will fully replace 300 million full-time jobs. About 2 in 3 jobs will be exposed to some form of AI automation, with some jobs disappearing altogether. Here’s how Goldman views the industries most at risk:

Administrative office work, legal work, and architecture & engineering lead the way. Here’s the extent of automation Goldman expects across industries:

If you work in maintenance, repair, or construction, you’re likely safe. If you work in admin or legal, you have a ~40% chance of being fully replaced by AI.

Many healthcare jobs should also be safe. In a survey last week, Bloomberg asked 678 investors about the future of work: 40% of respondents said that if members of Gen Alpha (children age 13 and under) want an AI-proof job when they grow up, they should work in healthcare.

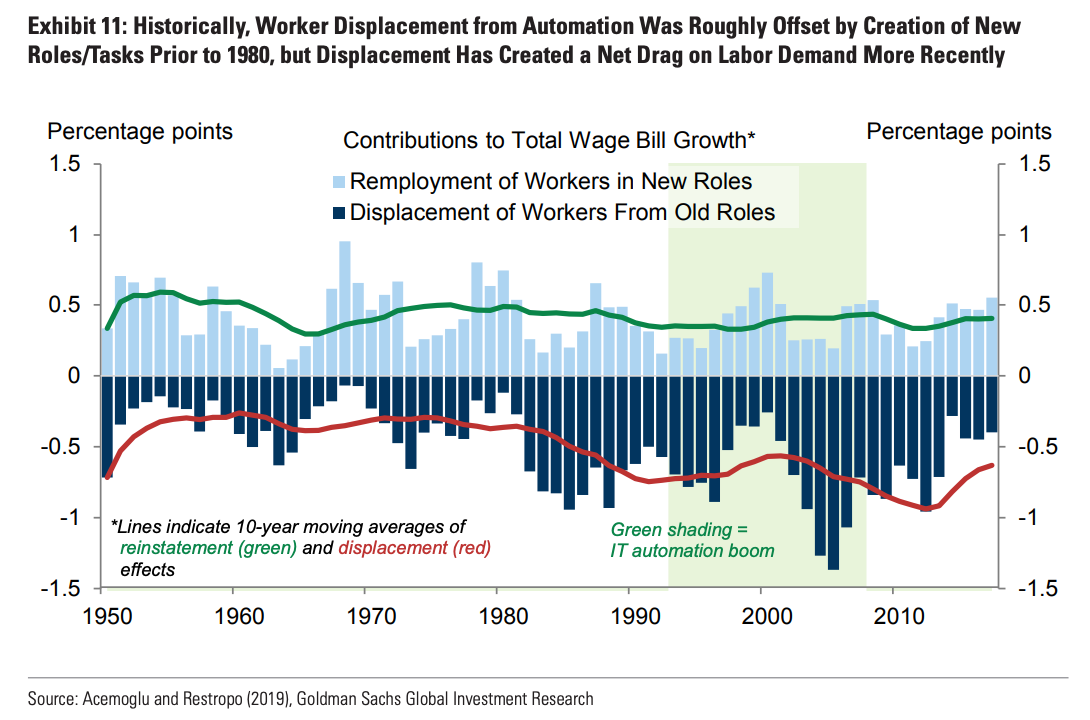

Another chart from Goldman’s report provides a rosier outlook. Historically, worker displacement from automation was roughly offset by the creation of new roles and tasks:

In The AI State of the Union, I argued that many modern jobs will soon disappear, and that this is a movie we’ve seen before:

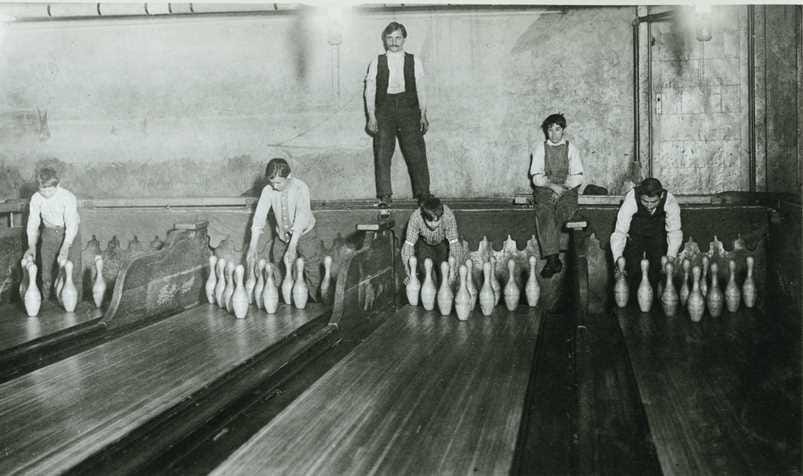

We’ve seen the same patterns in past technology epochs. Before there was automatic equipment to reset bowling pins, “Bowling Pin Setter” was an actual occupation. Ditto for “Lamplighter”—Lamplighters walked on average 10 miles per day, lighting lamps before dusk and distinguishing them at dawn. Will jobs like Executive Assistant, Copywriter, or Accountant follow the same extinction?

The silver lining: worker displacement from automation has historically been offset by the creation of new jobs. We’ll see jobs emerge that we can’t even think up yet (“Prompt Engineer” seems to be an early, and lucrative, example). Who would have thought 30 years ago that jobs like Cybersecurity Analyst, Database Administrator, or Machine Learning Engineer would exist? Let alone Social Media Manager, SEO Consultant, or Discord Community Manager?

This being said, there’s a lag effect; there will be short-term suffering while new jobs are created and while workers are retrained to perform those new jobs. Executive Assistants and Paralegals may need to be trained to be nurses or data scientists.

This is why we need an overhaul in education: our current system is set up for a world in which innovation moves slowly and in which mastery of one task can carry you through a 50+ year career. That’s no longer the case. A teenager today might work 3, 4, or 5 discrete “careers,” each requiring a distinct skillset.

We need more startups building systems to reskill and upskill workers at scale. Guild is one example: Guild offers “education-as-a-benefit” to employees at companies like Walmart, Taco Bell, Chipotle, Lowe’s, and Target. Why would companies pay for workers to get tuition-free educations? In short, better retention. Worker retention is a perpetual challenge for low-wage jobs—in the fast-food industry, annual employee turnover hovers around 150%. This means that not only are most employees leaving every year, but half of the employees hired to replace those leaving are also departing. Yikes. This is expensive—costs include 1) the time it takes a manager to hire a worker, 2) the time it takes to train that worker, and 3) the time that it takes that worker to become proficient at the job (typically a couple of months). Reducing churn by even a few percentage points can have big payoffs for large companies.

Guild capitalizes on this dynamic. Rachel Carlson, Guild’s founder, says: “In the fast-casual food sector, our analysis of 90-day retention rates found that 98% of frontline employees who pursued education benefits stayed with the company, compared to 73% of their peers.”

This gets at an important point: employers need to be the ones paying for worker training. More on that below when we dig into business models for next-gen education companies.

Skill-Based Learning

College is becoming untenable. A January 2022 survey from the ECMC Group found that only 51% of Gen Zs want to pursue a four-year college, down from 71% just two years ago. Meanwhile, 56% believe that a skill-based education makes more sense in today’s world.

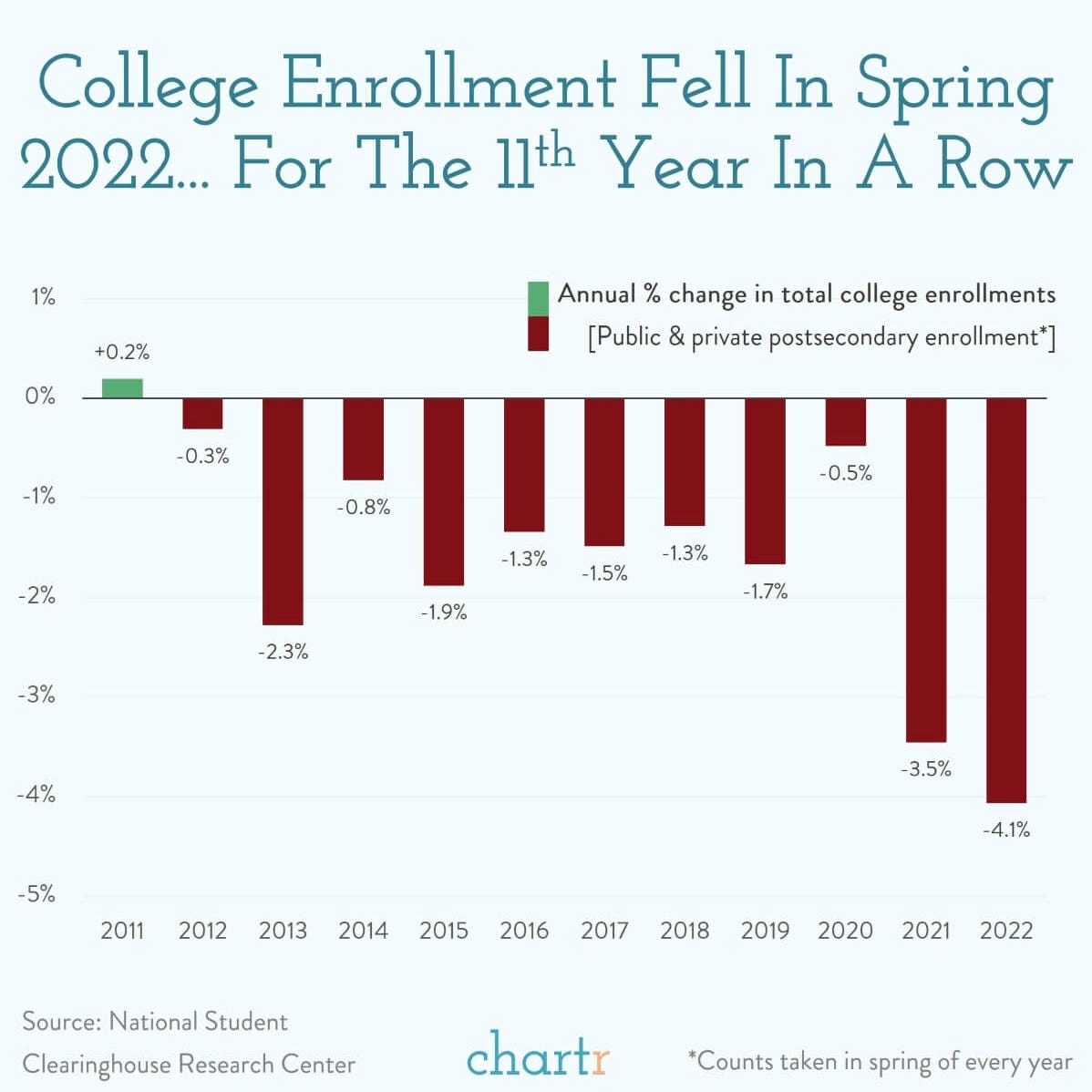

From fall 2019 to fall 2021, undergrad programs saw a 6.6% decline in total enrollment. This decline is sharper because of COVID, sure, but it also continues a long-term trend: college enrollment has declined for 11 years straight.

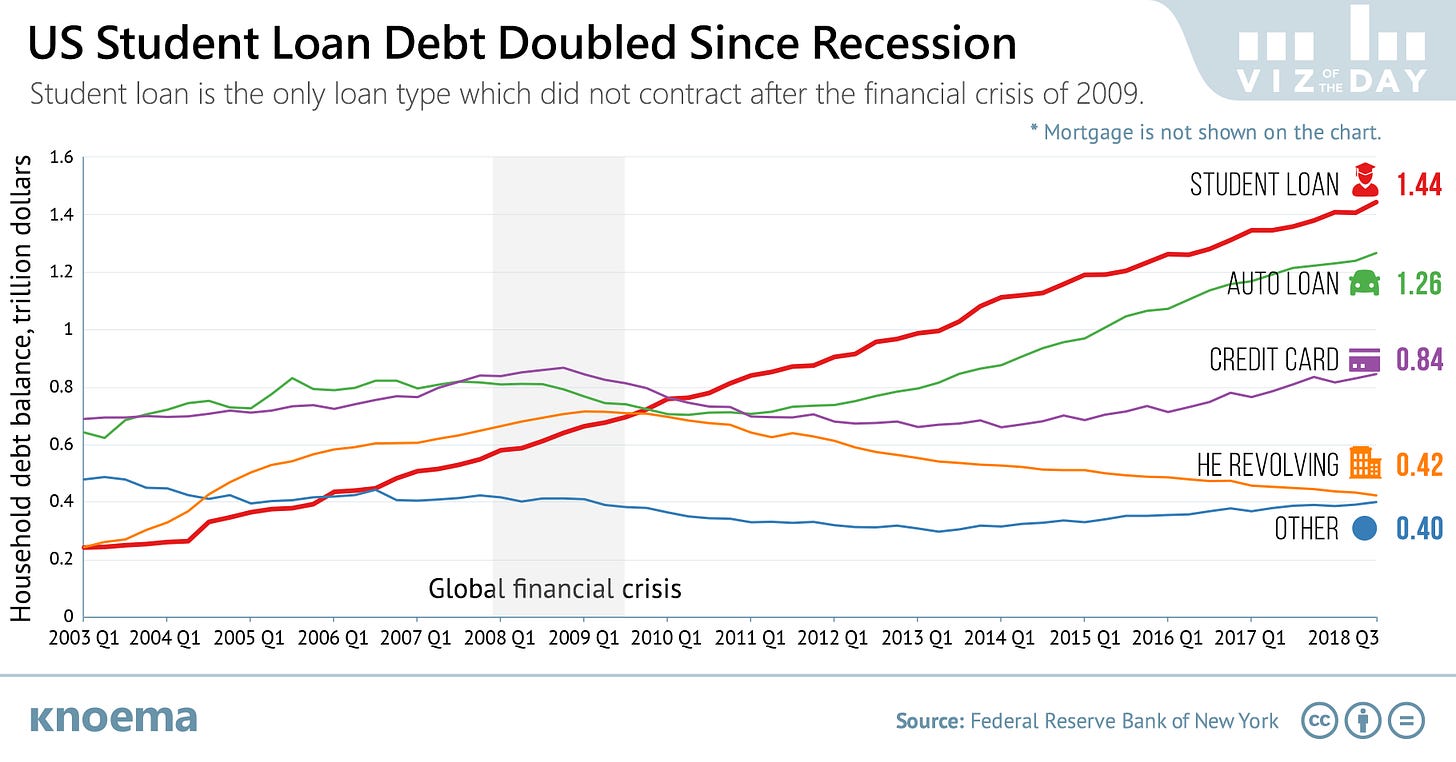

For many people, college is simply unaffordable. Student loan debt has ballooned, doubling to ~$1.5 trillion from 2008 to 2018.

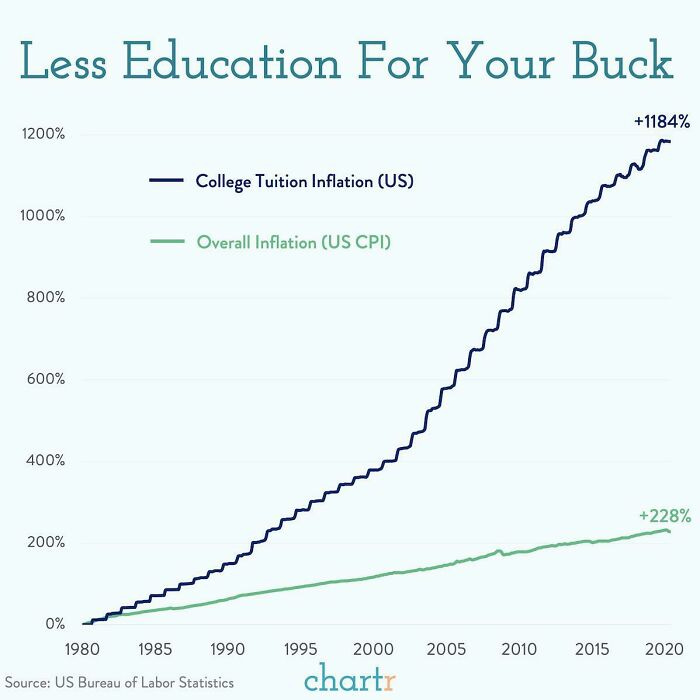

The cost of education is growing 8x faster than real wages. In the 1950s, 30% of household income was enough to pay for college. Today, people need to shell out 80% of their household income. Tuition costs have swelled +1,184% since 1980.

And college is less accessible to the less privileged: children born in the bottom income quartile in the US have just a 9% chance of achieving a college degree by age 25.

My view—which may be controversial—is that most people shouldn’t go to college. The return on investment just doesn’t make sense. For many, a skill-based program may be a better option. Reforge, for instance, is a startup that offers courses in growth marketing and product management taught by top tech executives. The mid-2010s saw the rise of MOOCs like Coursera, Udacity, and Udemy, as well as an influx of coding bootcamps propelled by income-share agreements. We’re now seeing the rise of field-specific training programs in domains like nursing, data science, and design.

Down the road, it may make for labor marketplaces to move upmarket into job training. Could Incredible Health train nurses? Could Nourish help certify dietitians? Could Seafair prepare a new generation of seafarers (the crew on shipping vessels)? The challenges for labor marketplaces include protecting against disintermediation (supply and demand circumventing the marketplace), facilitating discovery, and avoiding reacquisition of supply and demand for each gig. Providing an element of skill-based training could improve the stickiness of the marketplace.

What business models work in education?

Education technology companies often target two approaches, both of which have drawbacks:

Many rely on Learning & Development (“L&D”) budgets at enterprises, which are often viewed as non-mission-critical and are among the first to be cut in a downturn.

Many others sell into schools or school districts, which are challenging for a host of reasons: sales cycles are long and unpredictable; decision-makers vary across organizations (is it the superintendent, the principal, or the science teacher—or all three?); and budgets are thin.

Our education system is lethargic and corporations deprioritize training; these are the reasons education has changed little in 30 years, while technology has reinvented nearly every sector.

Because of these dynamics, startups need to get creative with how they monetize. Guild’s example above is one case study—proving to enterprises that you can save them money by reducing worker attrition is more powerful than appealing to their need to retrain employees. With AI obfuscating jobs, startups should appeal to specific incentives: a company may need fewer executive assistants, sure, but maybe it will need more data scientists or prompt engineers. Is retraining your existing workforce more economical than finding those new workers in the open market?

In a B2B approach, startups should find purchase drivers that are economic, not altruistic. And in a B2C approach, startups can circumvent the system altogether to go direct to learners or direct to parents.

Many of the business models touched on above are compelling. MMOs like Roblox offer robust virtual economies built on micropayments. These can yield massive businesses. Content platforms like YouTube and TikTok, of course, thrive on ad-driven business models; the key here is reaching enough scale to support advertising. Others have had success with subscription.

Synthesis is one example of the subscription route. Synthesis is a school that came out of SpaceX’s Ad Astra school. For $180 / month, Synthesis offers young students twice-weekly online courses (Wednesdays and Saturdays) with a cohort of peers and a trained instructor. Courses focus on team-thinking games that teach concepts like Risk and Negotiation. In this way, Synthesis builds on the edutainment concepts above, all through a subscription-based model that’s reached impressive scale.

Both B2B and B2C approaches to education startups can work. There are a few business models in technology that are desirable: advertising, subscription, micropayments, SaaS. Those are the approaches the best companies will take. The startups that reach escape velocity will likely avoid selling into schools—doing so makes it difficult to reach the acceleration needed for a venture-backed business—and will either sell into enterprises with a strong incentive, or sell direct to consumers.

Final Thoughts: Personalized Learning

The Holy Grail in education is personalized learning. This is why teacher-to-student ratios are so scrutinized; how much attention is each individual student receiving?

This is the promise of AI:

AI can act as a personal tutor, honing in on a learner’s specific focus area.

AI can automate grunt work for teachers—lessons plans, grading—and free up time for personalized instruction.

And AI can analyze a student’s specific strengths and weaknesses, producing personalized learning materials and exercises.

We’re early here; many schools are still scrambling to figure out how to co-exist with ChatGPT. But AI has tremendous promise as a companion for both teachers and students. In a new model, students might use AI for personalized lessons and exercises (replacing the lecture model and generalized homework assignments), then use valuable in-person time with teachers for specific help on difficult concepts.

There’s a lot more happening in education; this piece only begins to delve into some of the subsectors. The hope is that in 2033, education looks radically different—that (finally) the technology revolution turns its focus to an antiquated but massive industry long overdue for reinvention.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: