Gen Z, Creators, and Our Mental Health Tipping Point

Young People Are Leading the Mental Health Revolution

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Hey Everyone 👋 ,

You may remember we hosted the Index Creator Summit back in October. This month, we’re hosting the Index AI Summit. The Summit is January 19th and 20th and will include speakers like Fei-Fei Li, Sam Altman, Reid Hoffman, Kevin Scott, Cade Metz, Pieter Abbeel, and Alex Wang.

If you’re interested in how AI is changing the world, check it out. The event is virtual and open to everyone—you can sign up here.

With that, on to this week’s piece!

Gen Z, Creators, and Our Mental Health Tipping Point

At first glance, Hulu’s The D’Amelio Show looks like a Gen Z re-creation of Keeping Up With the Kardashians. The Kardashians, after all, are Instagram’s most successful family, while the D’Amelios are TikTok’s. The Kardashians dominated 2010s pop culture; the D’Amelios are poised (or at least aspire) to dominate the 2020s. Last week, Forbes released its ranking of 2021’s highest-paid TikTok creators. Charli D’Amelio—at 17-years-old, TikTok’s most-followed person with 133M followers—topped the list with a $17.5M haul. Her older sister Dixie—19 and TikTok’s 9th-most-followed person with 57M followers—slotted in at #2, with earnings of $10M.

But viewing The D’Amelio Show, you begin to realize that it reads less like entertainment and more like an educational warning of social media’s toxicity. The show is a genre blend of drama, horror, and tragedy, shining a garish light on the strains of being a creator. In the first episode, Dixie has an emotional breakdown. Charli admits (far too casually) that she sometimes suffers 15 panic attacks in a day. Both sisters talk about having thoughts of self-harm, and their therapists make regular appearances on the show.

Ultimately, The D’Amelio Show is a show about mental health.

We’re in the midst of a mental health crisis. Rates of depression in 14- to 17-year-olds grew 60% from 2009 to 2017. Suicide rates in young people have more than doubled in a decade. 43% of Millennials and Gen Zs report being “very concerned” about their mental health.

Our mental health crisis is closely related to our loneliness epidemic. I wrote about loneliness last spring in a piece called Digital Kinship:

A recent survey found that nearly half of Americans always or sometimes feel alone (46%) or left out (47%). Over half—54%—feel that no one knows them well. Across the Atlantic, half of Brits over 65 consider the television or a pet to be their main source of company.

Some aspects of the loneliness epidemic are a near-term shock. Covid, for instance, exacerbated loneliness: many “third places” (places beyond home and work—schools, coffee shops, bars, restaurants, gyms—where we seek connection) shut down. Other aspects of the epidemic are more gradual: community arts and recreation centers—part of the social fabric of a community—declined by 18% from 2008 to 2015. Gallup reported last year that U.S. church membership fell below 50% for the first time, a continuation of a sharp decline since 2000.

Our physical gathering spaces have been replaced by online communities. We find connection in Discord servers, in subreddits, in Twitch streams. We find friendship with online creators in parasocial relationships. Our new third places are digital.

Some people even seek connection by watching others sleep—every month, people watch millions of hours of “sleep streaming” on Twitch.

Loneliness is one component of the mental health crisis. Another is its near-opposite: the constant, 24/7 connectivity to billions of internet users.

I often think of the opening lines from Olivia Rodrigo’s song “Jealousy, Jealousy”:

I kinda wanna throw my phone across the room

'Cause all I see are girls too good to be true

With paper-white teeth and perfect bodies

Wish I didn’t care

The 18-year-old Rodrigo goes on to sing in the chorus, “Comparison is killing me slowly, I think too much about kids who don’t know me.”

Gen Zs, as digital natives, feel this most acutely. Gen Zs have grown up in a world of constant scrutiny, comparing the messiness of their own lives to other people’s airbrushed selfies and curated highlight reels. This takes a toll.

Startups like BeReal, Poparazzi, and Dispo have brought a less-performative approach to social media. But the titans continue to dominate, with minor product decisions influencing how billions of people see themselves. Instagram began as a literal filtered version of reality. Snapchat, a less high-stakes platform for sharing your life, still emphasizes beautifying filters.

To its credit, Gen Z is talking about mental health. Stigmas have been slowly eroding, replaced by vulnerability and candor. This started with Millennials but is accelerating with the rise of Gen Z. Look no further than the stark difference between Keeping Up With the Kardashians and The D’Amelio Show.

Gen Zs also understand the double-edged sword of the internet. One young woman told me, “I know that I need to limit my time on social media for my mental health. But I also know that the internet isn’t going anywhere and I can’t just not be online.” Her words reminded me of a line from the Chinese social media app Soul’s SEC filing:

We have especially attracted young generations in China, who are native to mobile internet and who therefore more palpably experience the loneliness technologies bring.

As more of our lives go digital, we more deeply feel the gaps where rich, in-person interactions used to be. Yet technology is also a salve for that isolation, connecting us in new ways to new people.

When it comes to mental health, creators occupy a uniquely precarious place. Creators build their careers on internet platforms, subjected to comparison and rejection and algorithmic whim. Beyond D’Amelio, creators have been candid about their mental health: the TikTok creator Avani Gregg, for instance, wrote a memoir called Backstory that dives into her anxiety and depression.

I spoke this week with my good friend Chris Olsen, an LA-based TikTok creator with 6.2M followers. Chris, who just turned 24, likened being a creator to being on a treadmill—an endless, nonstop pursuit of ideas and content and likes and brand deals.

When I asked Chris what aspects of being a creator are most challenging, from a mental health perspective, he pointed to:

The need to constantly produce content,

The pressure to meet or exceed a high bar, and

The lack of infrastructure for creators.

When Chris isn’t producing content, he isn’t earning income. There’s no concept of “PTO” in the creator economy. A week off means a week with no money. And Chris is only as good as his last few posts—if his metrics start to slip, brands value him less and he earns less money. Our conversation reminded me of this tweet from Ninja, once the most-popular streamer on Twitch:

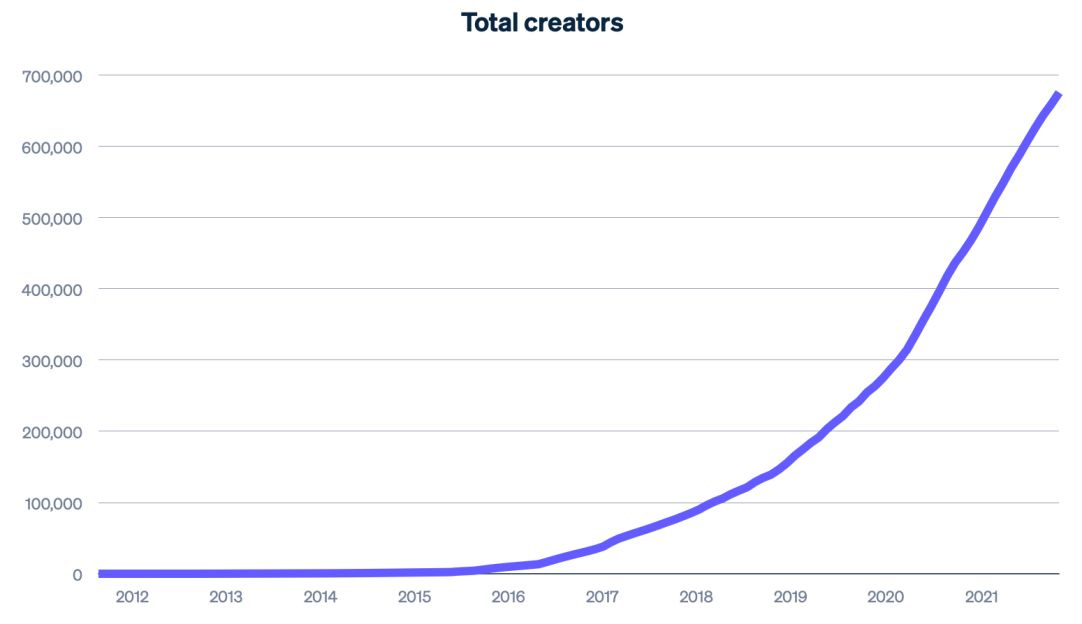

This is unsustainable. One option is for the platforms—TikTok, Instagram, YouTube—to offer creators PTO of some form. Another option is for a third-party benefits provider to build a solution. But as the number of creators skyrockets, a new infrastructure for work needs to be built.

By 2027, America’s workforce will be majority-freelance. But mental health, like most other benefits, is tied to traditional forms of employment. Self-employed people don’t have the same access to counseling, healthcare, or PTO. A worker at a company might tap into mental health through a corporate partnership with Modern Health—what’s the equivalent for the self-employed?

Getting this right is even more important as we see younger and younger people facing the same challenges. If we think Gen Zs are digital natives (with the scar tissue to show for it), Gen Alphas take things to an entirely new level.

Last week, The New York Times Magazine published a profile of Ryan Kaji. Kaji, just 10 years old, has been YouTube’s highest-paid creator for three years running. He commands an empire that includes his own product line, over 100 licensing deals, and merchandising deals with both Walmart and Target. Last year, Ryan’s World-branded products raked in $250M, with Kaji (or his parents, more specifically) pocketing $30M.

The Times profile wasn’t the first profile of Kaji—but it was the first that went behind-the-scenes of the Ryan Kaji empire. It revealed a clear tension behind protecting Ryan’s mental health and childhood—he’s only 10-years-old, but has been doing this for half his life—while still bringing in income to support an entire family. (Both of Ryan’s parents quit their jobs to oversee the Ryan’s World brand.)

Ryan’s dad says, “I was concerned about how much we could keep doing this without putting too much pressure on Ryan.” He and his wife take pains to minimize Ryan’s workload. They use techniques to reduce his time on camera; for example:

In one recent video, the action starts with Ryan in his backyard holding a rubber ball. He tosses it halfheartedly in the air, watches it bounce and then says that Peck and Combo — two of the cartoon characters in Ryan’s World — are going to teach viewers about gravity. He’s on camera for all of 35 seconds.

But Ryan is, despite their efforts, the center of gravity. He has to work. In one chilling part of the article, the author overhears a crew member tell Ryan, “If you finish this scene, you can play Minecraft.”

Ryan’s story is an extreme—most 10-year-olds aren’t million-dollar brands, and most creators aren’t building an empire on the scale of Ryan’s World. But his story underscores how important it is to get mental health right for creators, for Gen Alphas, and for all internet users.

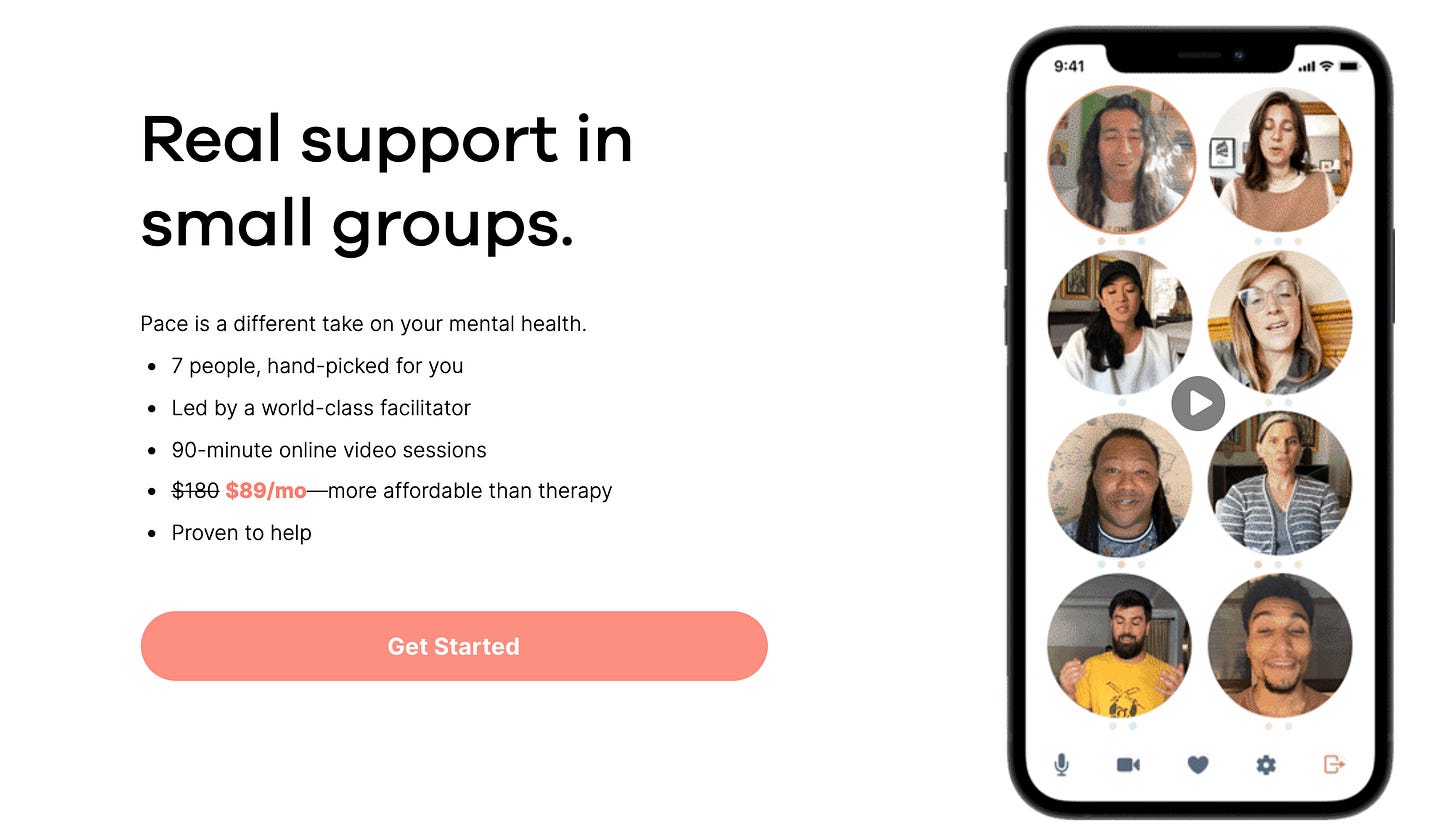

Part of this means building new systems for tapping into mental health resources. Marketplaces like Headway and Sondermind are making access to therapy easier and more affordable. Products like Calm and Headspace + Ginger (they recently merged) are tackling stress and anxiety. Companies like Real and Pace are leaning into the power of a community for mental health support.

For creators specifically, new forms of income may lesson the burden. A few creators I spoke to this week were working on ways to create passive income streams. One creator pointed to the YouTuber Emma Chamberlain’s coffee brand, Chamberlain Coffee: “If she takes a few days off for her mental health, she’s still making money.”

The creators I spoke to were working on jewelry brands, skincare lines, fragrances. Some were using services like Pietra and Trendsi to launch new business lines.

But new systems for mental health and new ways to earn income as a creator are both in their early innings. They’ll take years to take shape. More immediate—and even more important—is a generational shift in attitudes toward mental health. This is what enlivens me: we’re seeing a sea change in authenticity and vulnerability, led by Gen Z.

You see this is in the rise of Madhappy, Gen Z’s favorite streetwear brand. Where Supreme was about exclusivity and steely coolness, Madhappy is about loving your life and embracing who you are. It’s a sharp course correction.

Or take my friend Chris. I admire his candor around mental health—he regularly talks to his 6 million followers about going to therapy. He’s also begun somewhat of a tradition of posting crying selfies, a seemingly-small but deceptively-powerful display of vulnerability.

Or take Charli D’Amelio herself. In April 2021, Charli quietly started a second TikTok account, @user4350486101671, which has accumulated 15 million followers. Here, Charli is less polished and brand-ready, more loose and fun and carefree. In a small way, she’s reclaiming her agency.

What’s unique about mental health is that cuts a wide swath. Yes, it means therapy marketplaces and SaaS solutions. But it also means a revisiting of social media. It also means a rethinking of the gig economy and the creator economy, as our old infrastructure of mental health was provided (albeit poorly) by employers. Most of all, it means a breakdown of stigmas and a transformation in the cultural understanding of mental health.

Growing up, my dad used to tell me, “Depression or anxiety or mental illness are no different than a broken arm—they’re just an injury to a different part of your body, your brain, that needs to be taken care of like any other injury.” It feels like Gen Z is embodying that sentiment. The fervor with which they’ve changed the conversation around mental health—a conversation that is still just getting started—is what gives me hope.

Sources & Additional Reading

TikTok Made Them Famous. Figuring Out What’s Next Is Tough | Jon Caramanica, New York Times

The Boy King of YouTube | Jay Caspian King, NYTimes Magazine

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: