How AI Will Change Education

Predicting Innovation in Education, from Personalized Learning to the Downfall of College

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 60,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

How AI Will Change Education

Most industries change in the span of 100 years.

This is especially true when those 100 years include as much transformation as the past 100. Since 1924, we’ve gotten penicillin (1928) and the computer (1943) and space travel (1957) and the internet (1983) and CRISPR gene editing (2012). No 100-year period has microwaved so much innovation into a single century.

Yet…education looks pretty much the same. Here’s a Kentucky classroom in September 1920:

Look familiar? If you drop by a Kentucky classroom today, this is basically what you’ll get. You’ll see more kids texting, sure, but other than that not much has changed.

“Education” and “EdTech” are often considered bad words in venture capital circles. Why? Many education business models are subject to thin Learning & Development (L&D) budgets at enterprises. Others have to sell into lethargic school systems. Founders, no matter how creative, have to wade through bureaucracy—all in an effort to sell a vitamin, not a painkiller.

But there are compelling business models and go-to-markets in education (more on those later), and we’re at a breaking point where things need to change: the pace of technological advancement is accelerating, and our education system is still built for an Industrial Revolution-era world.

The prize is big: education was worth $1.6 trillion in the US in 2021, $4.7 trillion globally. For reference, that makes the American education market ~5x larger than the American advertising market, which supports tech companies like Google, Facebook, Pinterest, Snap, and Twitter. There’s clearly a lot of value to capture, but that value gets lost in a mess of mixed incentives and red tape. How can we unlock those trillions?

It’s gonna take a lot of work. A quick history lesson:

The first American public high school was established in Massachusetts in 1821. Fast forward 200 years, and our education system looks mostly the same. We lump education into the first ~20 years of life, we stick by analog teaching methods, and we fail to refresh curriculums for our modern world (35 states don’t teach any personal finance, but all 50 states learn that mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell). Today’s kids learn in much the same way that 1821’s kids learned—a time when Napoleon and Thomas Jefferson were still alive, and when Thomas Edison’s invention of the lightbulb was still 60 years away. It’s inevitable this will change—but when?

For a while, the question has been: which technology will be the disruptor that forces us to change how we teach and learn? The past 30 years saw the internet, mobile, and cloud seep into education—to mixed results.

Of course, many of the most successful tech companies are education companies in some way. YouTube, I’d argue, is the world’s biggest education company: 2.7B people use YouTube each month, 52% of global internet users; 86% say they regularly use YouTube to learn new things. Every day, we watch 5B distinct videos and consume 1B hours of video. Analysts recently estimated that YouTube would be worth $455B as a standalone company.

TikTok is also an education behemoth, and Roblox and Minecraft are, in their own ways, education companies that have birthed a new generation of developers.

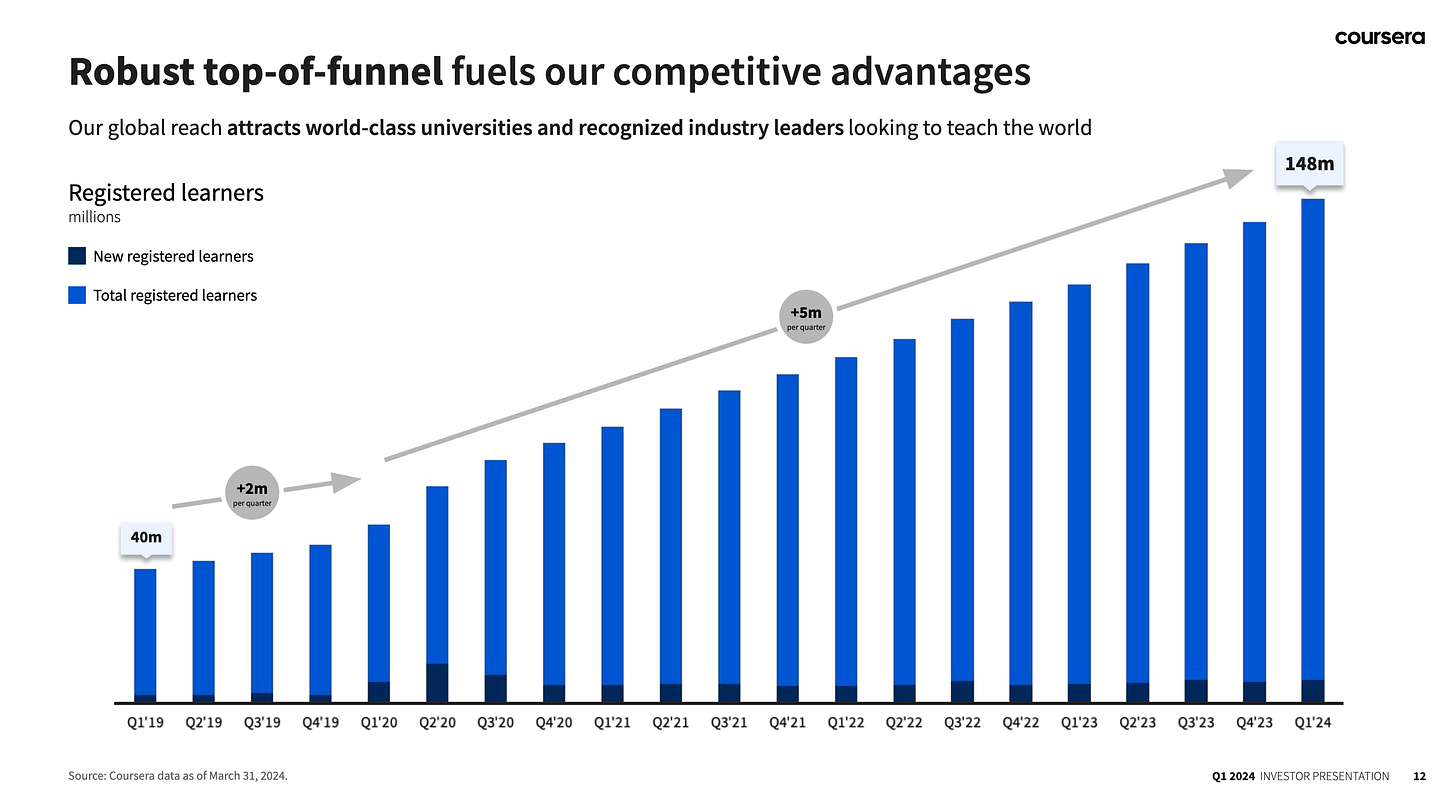

More pure-play EdTech startups have fared…okay. We have MOOCs—Massive Open Online Courses—like Coursera and Udacity, which experienced pandemic bumps and have largely kept that momentum momentum. (Coursera did $634M in top line last year, +21% year-over-year, but its stock is getting clobbered as the company keeps missing guidance.)

We also have edutainment—a blurring of entertainment and education that “gamifies” learning. When it comes to edutainment, I think of a quote from the tech philosopher Marshall McLuhan: “Anyone who tries to make a distinction between education and entertainment doesn’t know the first thing about either.” See: YouTube example above.

Duolingo is probably the best direct example of edutainment. It’s a public company that continues to impress; for fiscal year 2023, our favorite green owl posted:

$622.2M in Bookings, +45% year-over-year

$93.7M in Adjusted EBITDA, a 17.6% margin (compared to prior year’s $15.5M and 4.2% margin)

6.6M Paid Subscribers, +57% year-over-year

26.9M Daily Active Users, +65% year-over-year

Not bad—and good enough to earn Duolingo an $8B market cap.

So the last generation of EdTech companies weren’t terrible. But where are the $10B+ standalone education startups? With such a large market, so ripe for disruption, shouldn’t we have some decacorns?

The internet, mobile, and cloud all made a dent on education. But education still hasn’t been fundamentally reinvented. Now, all attention has now shifted to AI. Bond Capital recently put out a good report on AI and universities. Sal Khan, of Khan Academy fame, came out with a new book—Brave New Words: How AI Will Revolutionize Education (and Why That's a Good Thing). People are rightfully looking to AI as education’s next big thing.

My view: AI will (finally) be the change-maker education has waited for, though its impact on education will be muted by bureaucracy and old habits.

This week explores how AI will bleed into education, looking at three segments of education worth watching, then examining which business models will prevail.

Personalized Learning and Tutoring

Teacher Tools

Alternatives to College

Final Thoughts: Business Models and Why Education Matters

Let’s dive in 👇

Personalized Learning and Tutoring

The Holy Grail in education is personalized learning. This is why student-to-teacher ratios are so scrutinized; how much attention is each individual student receiving?

Thankfully, America’s student-to-teacher ratio has been falling over time—a rare bright-spot in education, as costs balloon and test scores suffer. We now hover around 15 students for every one teacher:

Of course, this varies by state: a student in Maine gets a lot more attention than a student in California.

And, naturally, student-to-teacher ratios vary by income. Lower-income schools can’t afford generous ratios, with fewer (low-paid) teachers spread thinly across large student bodies. This is why socioeconomic status is such a strong predictor of educational attainment, and it’s the elephant in the room for every conversation on education.

What’s exciting about AI: it can be the great equalizer.

With AI, every student can get an affordable, personalized learning path. In some ways, AI effectively lowers the student-to-teacher ratio to a 1-to-1 relationship. Technology can’t replace the human-level engagement of a good teacher or tutor, of course—but generative AI can get us closer than past technology breakthroughs.

The biggest education companies built this decade, in my mind, will be personalized learning and tutoring businesses.

High-income students continue to outperform lower-income students on standardized exams, largely because of an imbalance in tutoring. According to The Washington Post, “Students from families earning more than $200,000 a year average a combined score of 1,714 [on the SAT], while students from families earning under $20,000 a year average a combined score of 1,326.” Yikes.

AI will level the playing field. Human tutoring is expensive, and culturally it’s more widespread in Asia (where families have higher willingness-to-pay) than in the West. Across Asia, households spend ~15% of their income on supplemental learning. That’s 7x what the average U.S. household spends.

With personalized learning paths powering by machine learning and generative AI, students can now get individualized instruction for an accessible price.

There was an interesting study that came out this week: researchers looked at how AI impacts creativity. The study found that AI boosts creativity individually, but lowers creativity collectively. You can read the published study here.

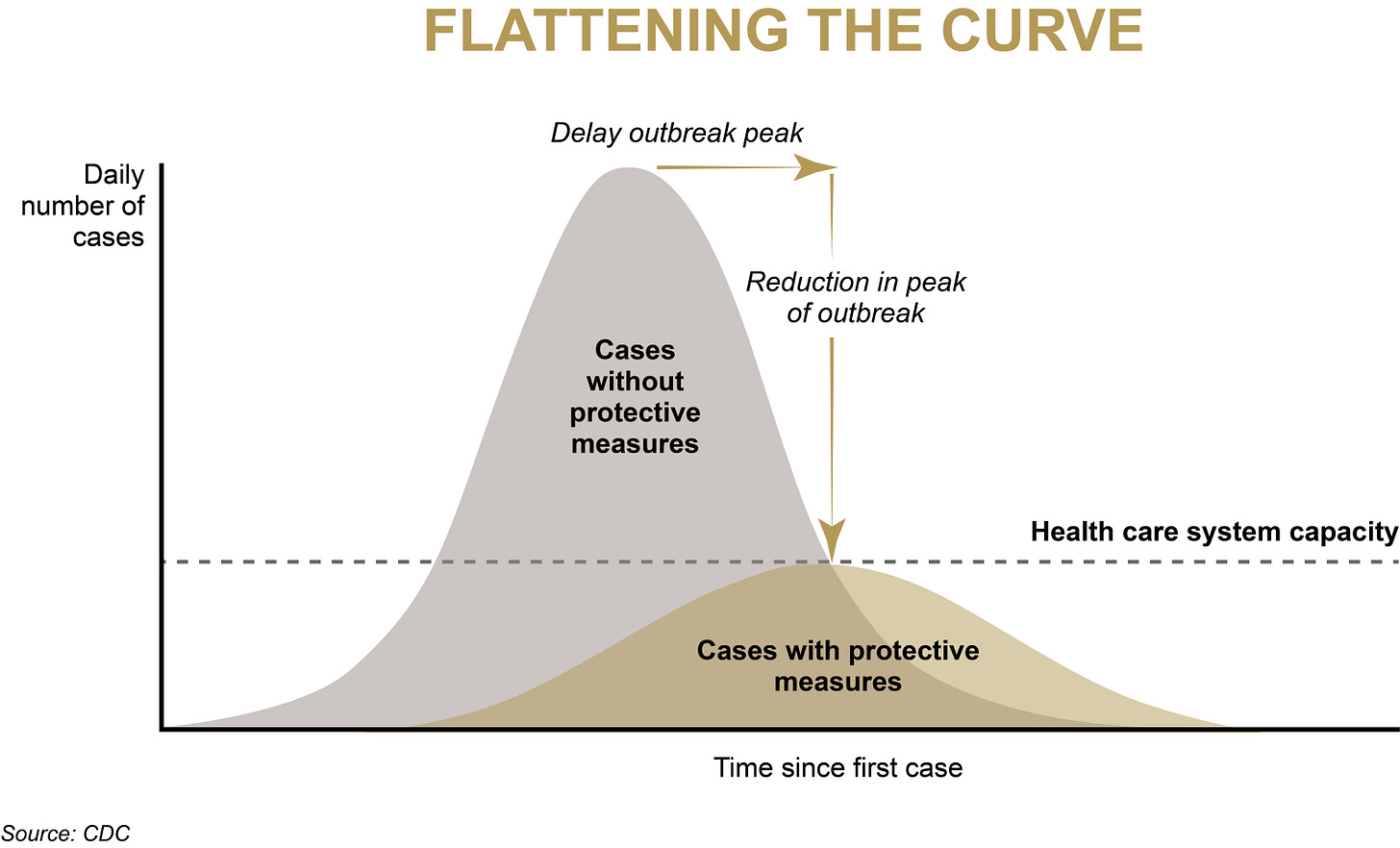

I think we’re going to see something with AI’s impact on knowledge. Remember “flattening the curve” from COVID? It reminds me of that.

AI will make everyone smarter through personalized learning, shifting the average up. But by improving individual instruction, it will also lessen the delta between high-performers and average-performers. This means flattening the curve. Fewer people will stand out, though we’ll collectively shift to the right; this will translate in the workplace through increased productivity, and GDP growth.

The tools that enable this will be those that can learn a learner’s strengths and weaknesses in real-time, then adapt personalized learning paths to maximize that learner’s knowledge. I expect many AI applications to be built for this use case, in K-12 all the way through workforce development.

Teacher Tools

Everyone is talking about AI agents (see: last month’s The Egg Theory of AI Agents) and it should be no different in education.

Earlier this week, Bloomberg reported that OpenAI internally shares definitions for five levels of artificial general intelligence (AGI). The five levels:

Chatbots: AI with conversational language.

Reasoners: Human-level problem-solving.

Agents: Systems that can take actions.

Innovators: AI that can aid in invention.

Organizations: AI that can do the work of an organization.

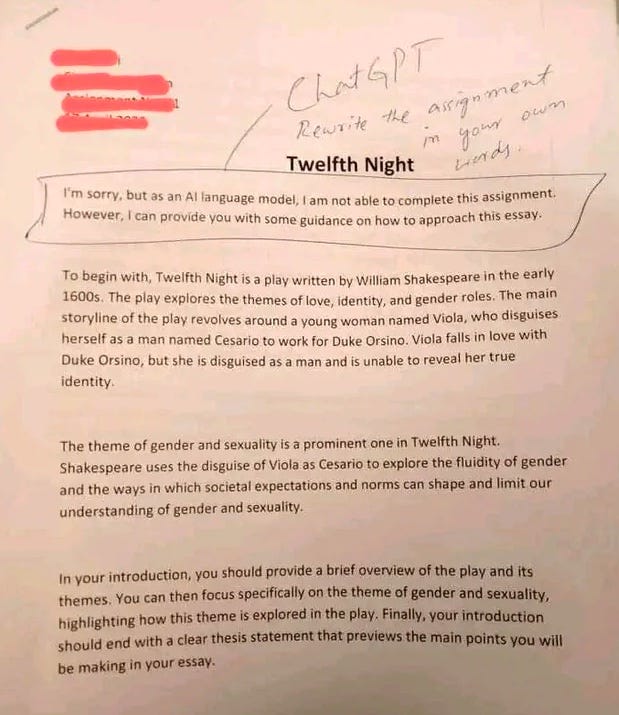

Clearly, ChatGPT covers #1. And ChatGPT is the biggest education product since YouTube, maybe even Google.

Student tools are interesting—I think we’ll see lots of “homework helpers” and such. Many will be ChatGPT wrappers, but others will skew closer to the personalized learning and tutoring products outlined in the prior section.

Just as interesting to me, though: tools for teachers. These are agents—or maybe one day “innovators” or “organizations,” to borrow OpenAI’s parlance—that can augment teachers in various parts of their work.

Lesson plans? We’ll have gen-AI applications for that. Grading assignments? Teachers will definitely let an agent do a first pass.

Education involves a lot of words—put differently, language. And the thing about Large Language Models is that they do well when trained on industries that are language-intensive. This includes many services industries—we’ve seen agents pop up for lawyers, investment bankers, insurance brokers. And education, one of the largest services industries out there, is a perfect fit for LLMs.

Alternatives to College

College is becoming untenable. A January 2022 survey from the ECMC Group found that only 51% of Gen Zs want to pursue a four-year college, down from 71% just two years ago. Meanwhile, 56% believe that a skill-based education makes more sense in today’s world.

From fall 2019 to fall 2021, undergrad programs saw a 6.6% decline in total enrollment. This decline is sharper because of COVID, sure, but it also continues a long-term trend: college enrollment has declined for 11 years straight.

Why? College is expensive and the ROI is unclear. Student loan debt has ballooned, doubling to ~$1.5 trillion from 2008 to 2018. (The average borrower takes 20 years to pay off their student loans!) Overall, the cost of education is growing 8x faster than real wages; tuition costs have swelled +1,184% since 1980. In the 1950s, 30% of household income was enough to pay for college. Today, people need to shell out 80% of their household income.

And college is less accessible to the less privileged: children born in the bottom income quartile in the US have just a 9% chance of achieving a college degree by age 25.

One interesting trend: skilled trades are on the rise. A recent survey from Thumbtack (so take it with a grain of salt) found that 73% of Gen Zs say they respect skilled trade as a career, putting it second only to medicine (77%); 47% were interested in pursuing a career in a trade. One potential reason: 74% say they believe skilled trade jobs won’t be replaced by AI. Skilled trade programs are seeing sizable increases in enrollment:

One of our Daybreak companies, still in Stealth, is building for skilled manufacturing workers—think welders at Boeing or machinists at Ford. These are specialized skills, often obtained in a trade school or vocational school. College isn’t necessary for them. I expect these jobs to become more sought-after, and for more students to pursue alternative forms of education as a result.

Of course, college isn’t going away entirely. For many—especially America’s upper crust—college was never about the learning anyway. It was about signaling.

We can see this in something called “the sheepskin effect”. The sheepskin effect shows that degrees, rather than skills, determine income. If you go to Stanford and drop out after seven of eight semesters, you’d theoretically expect to earn 7/8 the income of a Stanford graduate; after all, you learned 7/8 of the skills. But instead, you can expect to earn 50% as much. That final eighth doesn’t deliver half the learning; instead, completing the degree is a signal to employers.

College isn’t just a signal—it’s an American rite of passage. I love this quote from Ian Bogost in The Atlantic:

Quietly, higher education was always an excuse to justify the college lifestyle. But the pandemic has revealed that university life is far more embedded in the American idea than anyone thought. America is deeply committed to the dream of attending college. It’s far less interested in the education for which students supposedly attend.

[Education] is just a small part of college’s purpose. In the United States, higher education offers a fantasy for how kids should grow up: by competing for admission to a rarefied place, which erects a safe cocoon that facilitates debauchery and self-discovery, out of which an adult emerges. The process—not just the result, a degree—offers access to opportunity, camaraderie, and even matrimony. Partying, drinking, sex, clubs, fraternities: These rites of passage became an American birthright.

No technological breakthrough can erode this part of American culture. This is why college—at least for the top schools—won’t change much. The Ivies will look the same in 2034 as they do in 2024. But I expect many universities will wind down (COVID already precipitated record shut-downs), with more students skipping out on an overpriced degree for a vocational degree, trade school, or workforce development program (“Amazon University” anyone?).

Final Thoughts: Business Models and Why Education Matters

We touched on this above, but education technology companies often target two approaches, both of which have drawbacks:

Many rely on Learning & Development (“L&D”) budgets at enterprises, which are often viewed as non-mission-critical and are among the first to be cut in a downturn.

Many others sell into schools or school districts, which are challenging for a host of reasons: sales cycles are long and unpredictable; decision-makers vary across organizations (is it the superintendent, the principal, or the science teacher—or all three?); and budgets are thin.

Our education system is lethargic and corporations deprioritize training; these are the reasons education has changed little in 30 years, while technology has reinvented nearly every sector.

I do expect education will change dramatically from AI, but not at its most fundamental. If we carry forward the image of the American classroom another 100 years, I bet it looks largely the same.

The mode of teaching, though, may be different. I think it will become commonplace for students to do AI-powered personalized learning on a tablet. The teacher will walk around the room and address specific questions, offering help as needed. Rather than deliver a one-size-fits-all lecture to 20 kids, kids will receive tech-driven individualized instruction with occasional 1-to-1 human tutoring and question-answering. That’s my prediction. I hope it pans out.

College, meanwhile, will look largely the same, though its downward trend of enrollment (and upward trend of cost) will continue. Millions of students will instead turn to apprenticeships, vocational training, or employer-sponsored job-specific learning.

The same question will continue to loom over education: who pays?

The issue with the products for teachers mentioned earlier: it’s tough to ask teachers, already underpaid, to shell out for AI-powered teaching products. But schools and districts aren’t exactly swimming in cash either.

I expect we’ll continue to see a lot of direct-to-learner products, particularly in tutoring and personalized learning. These are products that students (and parents) pay for directly. These products avoid the thorny school go-to-markets, acting more like consumer applications.

When it comes to lifelong learning and workforce development, employers need to be the one paying. This means it’s incumbent upon the startup to show ROI in a clever ways. (Guild is one example, offering “education-as-a-benefit” to employees at companies like Walmart, Taco Bell, Chipotle, Lowe’s, and Target. Why would companies pay for workers to get tuition-free educations? In short, better retention. Worker retention is a perpetual challenge for low-wage jobs—in the fast-food industry, annual employee turnover hovers around 150%. This means that not only are most employees leaving every year, but half of the employees hired to replace those leaving are also departing. Reducing churn by even a few percentage points can have big payoffs for large companies, and that’s what education-as-a-benefit does. Rachel Carlson, Guild’s founder, once said: “In the fast-casual food sector, our analysis of 90-day retention rates found that 98% of frontline employees who pursued education benefits stayed with the company, compared to 73% of their peers.” We’ll need more clever business models like Guild’s for education to be scalable and align incentives.)

So why does all this matter?

The thesis for Daybreak is that the companies that define the next generation will be those that make life better for the next generation. Founders solving real, tangible problems have an advantage in attracting great talent.

We build this thesis around five pillars; of the five, “Learning” is the pillar we’re most under-invested in. But the time is ripe for education—I do think we’re at a watershed moment.

I’ve always had a love for education. Education is a tangible and emotional industry; you can see the moment a learner “lights up” with understanding and masters a concept or a task. And education is directly tied to economic opportunity and economic mobility, but has historically been gated by access. The promise of technology, of course, is to broaden access—and technology should make good educations accessible to more people.

I think AI will finally be the catalyst for change, though it will fight countervailing winds—bureaucracy; debates over who should pay; and the pesky issue of “but that’s how it’s always been done.”

Sources & Additional Reading

Bond Capital recently put out a good report on AI and universities

Sal Khan, of Khan Academy fame, came out with a new book—Brave New Words: How AI Will Revolutionize Education (and Why That's a Good Thing)

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: