How Impact Investing Applies to Venture Capital

Exploring Startup Innovation in Education, Healthcare, and Climate

This is a weekly newsletter exploring how technology and humanity collide. If you haven’t subscribed, join 40,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

How Impact Investing Applies to Venture Capital

In the 1970s, the economist Milton Friedman introduced the notion of “shareholder primacy”—put simply, the idea that “the business of business is business.” In Friedman’s exact words: “The social responsibility of a company is to make profits.”

Known as Friedman’s Doctrine, the concept of maximizing shareholder value infiltrated American capitalism. In the 50 years since, it’s had a stranglehold on us. One of my favorite cartoons summarizes the effects:

The problem with shareholder primacy is that it incentivizes short-term gains by sacrificing long-term value creation.

The story of General Electric—once America’s most-revered company—offers a good case study. While Friedman may have introduced the economic principles behind shareholder primacy, GE overlord Jack Welch popularized them. In 1981, Welch delivered a speech called “Growing Fast in a Slow-Growth Economy” that’s often credited with ushering in the obsession with shareholder value.

Here’s GE’s market cap over time:

In the 90s, GE was consistently the largest company in the world by market cap; today, it hovers around $90B, good for 154th place.

In recent years—particularly after the Great Recession—the concept of stakeholder capitalism has become more popular. Klaus Schwab, the founder of the World Economic Forum, has led the charge, arguing that two stakeholders should take precedence: people and planet. One level more granular, the idea is that businesses should take into account the needs of shareholders, yes, but also the needs of employees, customers, suppliers, and society at large.

Delivering value to all of a business’s stakeholders, the argument goes, ultimately delivers more long-term value to shareholders. (For what it’s worth, in 2009 Jack Welch criticized the relentless focus on share prices, calling it “the dumbest idea in the world.” Even the movement’s loudest advocates are rethinking the approach.)

Earlier in my career, I worked at The Rise Fund, the world’s largest impact investing fund. Rise counts Bono as a co-founder, and I often think of something he once said: “Capitalism isn’t moral or immoral, but amoral—it’s up to us to shape how it’s wielded.” Capitalism can be a tremendous force for lifting people out of poverty or even for saving lives (mRNA vaccines are a recent example that comes to mind), but incentives need to be aligned and guardrails need to be in place.

Rise was the first impact fund to attempt to measure and track social impact, using a tool we called the Impact Multiple of Money. You can think of the Impact Multiple of Money (IMM) for impact returns like you think of the Multiple of Money (MoM) for financial returns. Just as an investor may earn a 5x financial return on her investment (5x MoM), she may similarly earn a 5x impact return (5x IMM).

Here’s a simplified example:

Our second investment out of The Rise Fund was in Dodla Dairy, India’s 3rd-largest producer of fresh dairy products. Initially, it might seem like Dodla’s impact comes from the nutritional benefits of more milk and dairy. But Dodla’s impact actually comes from income uplift to smallholder farmers.

Smallholder farmers are farmers who operate on a small scale—a smallholder farmer may own only a single cow, for instance. There are 120 million smallholder farmers in India and 60% live in poverty; the average earns $2 per day.

Many dairy farmers try to sell their milk in the open market each day, but can’t find a buyer. Their milk spoils and they go home empty-handed. Working with Dodla, farmers enter long-term contracts that offer reliable daily purchases of milk. This leads to a doubling of annual income for Dodla’s 250,000 farmers.

Here’s how the IMM math might work (using directional numbers to prove the point):

In other words, for every $1 that Rise invests in Dodla Dairy, it expects to generate $5 of positive social impact.

Financializing impact can get tricky. The above example is relatively straightforward. Climate is also fairly straightforward: we have lots of data on the economic impact of carbon removal, for instance. Same goes for education: it’s easy to measure the income uplift from higher-quality learning. But what happens when you invest in a company like Zipline, which uses drones to deliver life-saving blood in sub-Saharan Africa—how do you put an economic value on a human life?

Impact measurement is fascinating and imperfect. But it’s a forcing function for thinking through how capitalism can generate impact at scale.

What captivates me about technology is how it can better ignite and amplify impact. Entrepreneurship is the engine behind everything: innovation is the purest distillation of potential energy. And if entrepreneurship is the spark, technology is the kerosene that uses zero marginal costs to grow the fire.

I often think about how “impact investing” can be applied to the startup ecosystem. My definition of “social impact” has expanded over time (more on that below), but it’s productive to think through innovation happening in key “impactful” sectors. In this piece, I’ll focus on three—Education, Healthcare, and Climate. I’ll also look at an offshoot of each—what you might call a “squishier” category that’s more amorphous and harder to pin down, but that’s emblematic of a massive consumer behavior shift. These are Learning, Wellness, and Sustainability.

Education | Learning

Healthcare | Wellness

Climate | Sustainability

Within each, I’ll mention a few timely startups that embody innovation and impact.

Let’s dive in.

Education | Learning

The first American public high school was established in Massachusetts in 1821. Fast forward 200 years, and our education system looks mostly the same. We lump education into the first ~20 years of life, stick by mostly-analog teaching methods, and fail to refresh curriculums for our modern world (35 states don’t teach any personal finance, but all 50 states learn that mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell).

Does it make sense that things haven’t changed in two centuries? Today’s kids learn in much the same way that 1821’s kids learned—when Napoleon and Thomas Jefferson were still alive, when Thomas Edison’s invention of the lightbulb was still 60 years away.

In the last 25 years, we’ve gone from Nokias to iPhone 14s and from 10% of Americans on the Internet to 90%+. Yet the education system has barely shrugged. Worse, it has deteriorated in quality and access: the cost of education has grown 8x faster than the rate of inflation-adjusted wages.

Here are three charts from Chartr that give a snapshot of modern education:

First, college tuition costs have grown +1,184% since 1980.

As a result, college enrollment has fallen 11 years in a row. You can see the COVID acceleration in the last two years.

Also as a result of COVID, kids are scoring worse on tests. We’ll be seeing the ripple effects of the “lost years” of schooling on pandemic-impacted kids for decades.

Education is in a dire state, and it’s difficult for startups to reinvent the system. Selling into schools can be a nightmare. First, do you sell into the school or district level? Then, who do you sell into? There are various decision-makers—teachers, principals, superintendents. You may need sign-off from all of them, or the primary decision-maker may vary by school. Tack on thin budgets and long sales cycles, and it’s no wonder our education system is so lethargic.

That said, there are compelling startups injecting new energy into that lethargy. PrismsVR, for instance, uses virtual reality to better teach math. Available on MetaQuest, Prisms offers students experiential learning in 3D modules aimed at teaching abstract concepts like algebra and geometry. The company sells both into school administrators and into parents. It’s not an if, but a when for virtual reality reinventing education.

An offshoot of innovation in education is innovation in learning.

I’ve begun to separate the two concepts in my mind. “Education” can be limiting in that it makes us think of traditional education—the K-12 and higher-ed experiences consumed in the first ~20 years of life. “Learning,” meanwhile, connotes something living and breathing and evolving, rather than something static.

Today’s education system was built for a post-Industrial Revolution world. It made sense then: 1) learn a skill, 2) practice that skill for 50 years. But it doesn’t make sense in a world as fast-changing as our digital world today. I made this image two years ago, but it still holds.

If I could reinvent our education system, early years would focus on “learning to learn” and later years would focus on job-specific skills. Some startups are pushing us toward a world like this. Reforge, for instance, reinvents skills-based, job-relevant learning with a scalable and community-centric format. With Reforge, you can take courses like Data for Product Managers, Growth Marketing, and Monetization + Strategy. Each course is taught by experienced leaders from the field:

Reforge uses a clever model of low-cost, evergreen production to scale its courses and better leverage its experts. The goal is to tap into the latent knowledge that all knowledge workers have—“the expert economy”—and channel that knowledge into training the next generation of workers. Rather than education being about degrees and signaling, it becomes about tangible skills. Reforge is more of a learning company than a traditional education company.

This is the future of the sector: more digitized, tech-enabled classrooms, and more lifelong and scalable job-specific learning. COVID was an inflection point, but the real catalysts are the pace of change in the job market and the staleness of the modern education system.

Healthcare | Wellness

Healthcare is the only sector that employs more Americans than education, counting 22 million workers (14% of the workforce). This is only going to increase as our population ages rapidly:

Below are the fastest-growing fields for job openings in the 2020-2030 decade. The blue bubbles are healthcare-related. The largest bubble on the bottom left is “Home health and personal care aides”—workers to help care for Boomers as they age.

There are interesting startups building along this shift: Papa offers companionship to the elderly; Birdie, a company we’ve partnered with at Index, offers an end-to-end software solution for senior living and home care; Perry Health lets you care for your diabetes from home.

Another segment within healthcare that has tremendous tailwinds: mental health. A devastated report from the CDC on Monday found that teenage girls are in the midst of the worst mental health crisis in decades—nearly three in five teenage girls felt persistent sadness in 2021, double the rate of boys, and one in three girls seriously considered attempting suicide.

There are fewer more urgent areas for innovation, and we’re thankfully beginning to see some companies tackle the youth mental health crisis.

Cartwheel blends education and healthcare, partnering with schools to provide students with access to mental health assessments, evidence-based therapy, and medication evaluation, entirely via telehealth with licensed clinicians.

New forms of treatment, like ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP), are also being explored. Journey Clinical is a startup that gives licensed mental health professionals the tools to deliver KAP, while offering patients the ability to get matched with a psychotherapist for personalized care. At its core, Journey is a decentralized clinic and B2B marketplace connecting those in need with those able to deliver care.

The more holistic, amorphous offshoot of Healthcare is “Wellness.” While “Healthcare” brings to mind products sold to providers and payers, “Wellness” brings to mind a broader mindset shift in the American population.

We see this emphasis on wellness in the products we buy—Peloton and Tonal in connected fitness, Oura Ring and Whoop in wearables, Eight Sleep as we (finally) pay more attention to sleep.

We see this in how we pay more attention to our diets, and in how we seek better pediatric care for our children. I covered many of the startups building here in last month’s How Startups Are Combatting America’s Obesity Epidemic.

People are paying more attention to their health and wellness, and those lifestyle changes are an important component of addressing our various healthcare crises.

Climate | Sustainability

Climate change is out of control.

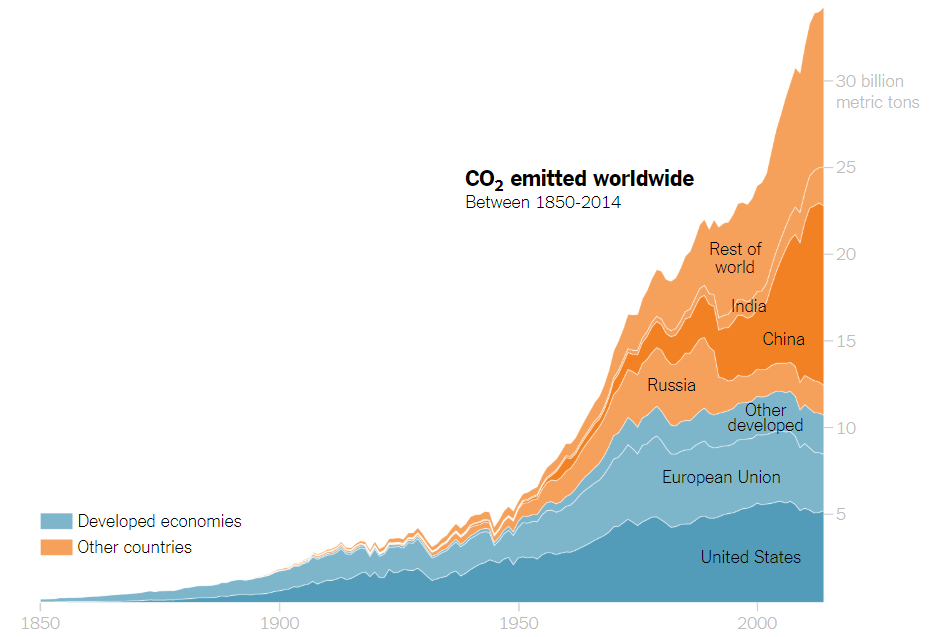

Global temperatures have steadily risen over the past century, in tandem with the rising C02 emissions shown above.

And if you think, “Hmm but the planet has gone through different climates over time—maybe this period is one of those,” here’s a zoomed out view that shows the trend over thousands of years.

Sometimes an image is more powerful than a chart. Here’s Alaska’s Muir Glacier photographed from the same vantage point in 1882 and in 2005.

And here’s the Great Barrier Reef, which is seeing more than 70% of its coral bleached by rising ocean temperatures.

One area of climate tech that’s gotten a lot of attention is carbon accounting. How can companies better measure their carbon footprints? Watershed is the buzziest startup in the space, attracting customers like Shopify, Stripe, DoorDash, and Airbnb. My view is that this market will evolve into a series of vertical-focused players: Watershed may be best at measuring the footprint for technology companies, for example, while other companies may have an edge in Industrials or CPG.

Iconic Air, for instance, focuses on carbon accounting for the world’s most energy-intensive industries. Over 56% of the world’s emissions come from just a handful of industries: Oil & Gas, Utilities, Manufacturing, and Metals. Those sectors are Iconic’s focus, building SaaS tools for “dirty” companies to better understand their footprints.

And what do companies do when they know how much they emit? They buy offsets. Right now, many do this willingly—Disney, for instance, recently expanded its voluntary carbon offset program. But much of this altruism is pulling forward the inevitable, as regulation ramps up (and locking in better prices to boot). Soon, every company will be required to offset.

At Index, we’re investors in Sylvera, which you can think of as S&P or Moody’s for carbon offsets. Sylvera gathers Earth observation data and trains machine learning models that can estimate carbon stocks from space, in real-time and with impressive accuracy. This way, big companies like Chevron, Salesforce, and Delta (all customers) can know the quality of the offsets they’re purchasing.

The rise of climate tech goes hand-in-hand with the rise of sustainability. “Sustainability” is a catch-all that encompasses behavior shifts in how companies conduct business and in how people consume goods and services—two sides of the same coin.

One amusing recent example of sustainability: the rise of the deinfluencer. Deinfluencing videos popped up on TikTok at the beginning of the year, as an attempt by influencers to tell their followers what not to buy under the guise of combatting overconsumption. But, of course, deinfluencing has evolved into its own form of capitalism; as Dazed writes:

Yet, as is often the case online, what started as an honest, user-led intervention into our collective consumer behavior, has been co-opted by influencers to shill even more products. ‘Deinfluencing’ videos have metamorphosed into a viral video format in which influencers are slating products they didn’t like and redirecting followers to other products or their ‘dupes’. In essence, most ‘deinfluencers’ on the app are really influencers in sheep’s clothing.

Deinfluencers aside, the tailwinds behind sustainability are strong. Younger shoppers in particular pay close attention to where they shop and to the values of the brands they spend with. Brands, meanwhile, are hustling to clean up their acts.

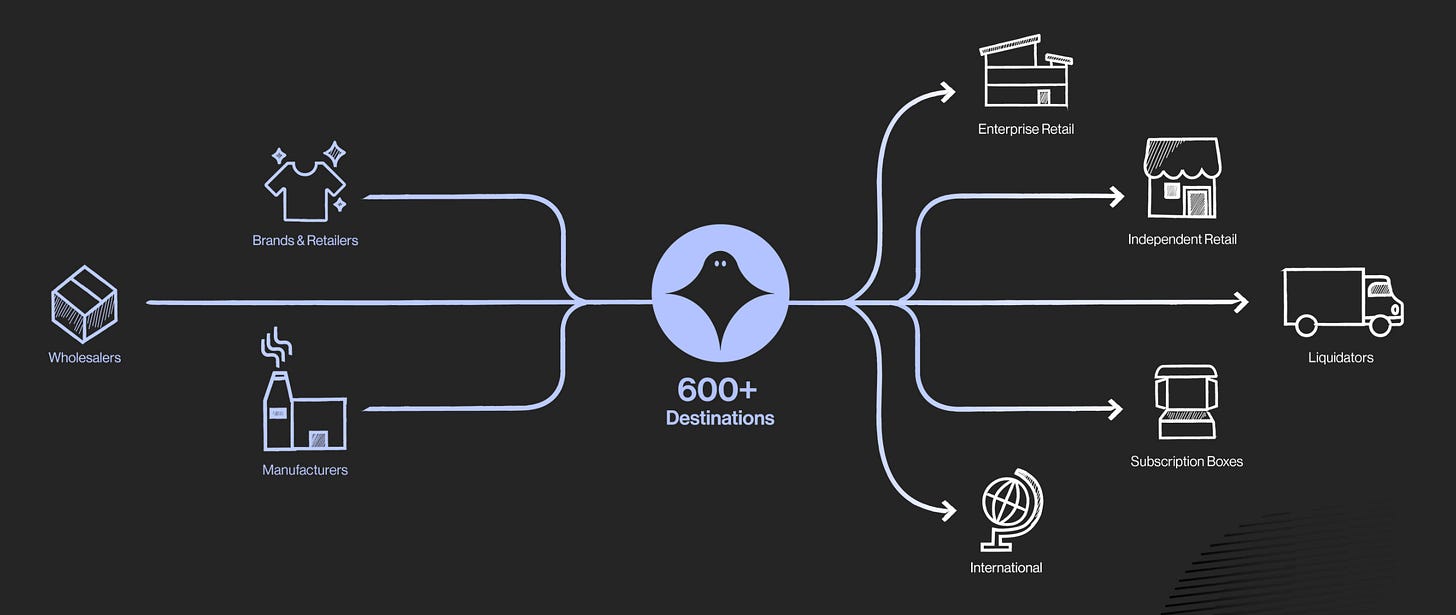

A slew of commerce startups are helping them do so. Ghost, for instance, is a B2B platform for surplus inventory. Brands overproduce more than $500 billion of goods annually, and Ghost helps route that excess to the right channels.

While Ghost tackles things from the B2B angle, companies like The Rounds go B2C. The Rounds delivers household essentials to your door in reusable bags and refillable containers, skipping the cardboard and single-use plastic.

Climate change may be the defining “tailwind” of our generation, reinventing every category of business. The startup world will play a key part in innovating our way out of this crisis (or so we can hope), both with more traditional climate tech solutions and with first- and second-derivative companies that expedite the consumer behavior shift to sustainable business.

Final Thoughts: Reframing Impact

So, does impact investing apply to venture capital?

Yes, in that many startups go on to create meaningful social impact at scale. Venture capital is unique in that in order to make money, things have to go very, very right. Venture is a form of investing rooted not in financial engineering or market manipulation, but in optimism. Entrepreneurship—the act of setting out to create something that doesn’t exist—is likewise rooted in optimism. Not all startups, of course, power positive change; most tech companies have both positive and negative externalities, and we need to do our best to amplify the good and curb the bad.

Over the years, I’ve come to have a broader definition of impact. Many of the most transformational tech companies wouldn’t fit neatly into “impactful” sectors. I wrote last week about how Instagram and Tinder could and should be considered impactful—and as I write this on Valentine’s Day, shoutout to Tinder for bringing my partner Ian into my life.

Or consider companies that become platforms for new forms of work, enabling far more livelihoods than the employees who show up in their SG&A line item:

Number of sellers on Amazon: 6.3 million

Number of FTEs: 1.5 million

Number of channels on YouTube: 51 million

Number of FTEs: 2,000

Number of artisans on Etsy: 7.5 million

Number of FTEs: 2,500

Number of developers on Roblox: ~400,000 “monetizing” developers

Number of FTEs: 2,000

These numbers are directional and imperfect; not all of those 51 million YouTube channels, for instance, are individuals earning a living. But they speak to the breadth of job creation on internet platforms. In The Rise of the Digitally-Native Job last fall, I looked at newer examples: musicians on Splice, resellers on Depop, gaming coaches on Metafy, experts on Office Hours. Younger examples—all Seed-stage companies—include career coaches on Leland, boutique merchants on Flagship, and dietitians on Nourish (though Nourish hires dietitians as FTEs). These companies are deeply impactful in how they enable people to earn a living in more autonomous, flexible, economically-rewarding ways.

At the end of the day, businesses need to make money. Generating sustainable cash flows is what enables impact at scale; otherwise, a company would be forever reliant on external capital (this dynamic exists in the non-profit world). Thoughtful government policy and meaningful philanthropy have important roles to play, but capitalism is a powerful mechanism for social impact.

Business just needs to be done the right way. The irony is that being more focused on “stakeholders”—treating employees well, engaging with local communities, taking care of the planet—will ultimately deliver more value to shareholders. A focus on near-term profit is often destructive.

One of my favorite passages about business comes from Phil Knight’s Shoe Dog, about the founding of Nike:

For some, I realize, business is the all-out pursuit of profits, period, full stop, but for us business was no more about making money than being human is about making blood. Yes, the human body needs blood. It needs to manufacture red and white cells and platelets and redistribute them evenly, smoothly, to all the right places, on time, or else. But that day-to-day of the human body isn’t our mission as human beings. It’s a basic process that enables our higher aims, and life always strives to transcend the basic processes of living.

Of course, Nike has had its own fair share of criticisms over the years. But the passage captures something important: business is about more than maximizing the share price—and when companies realize this, they attract the best employees, cultivate productive cultures centered around a shared mission, and consequently see their share prices rise.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: