This is a weekly newsletter about how culture and technology intersect. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

How Neopets Paved the Road to the Metaverse

When we look back on the road to the metaverse—to an immersive, pervasive, always-on collection of virtual worlds—we’ll point to milestones along the way. We’ll point to Fortnite, which taught us to socialize with friends in avatar form. We’ll point to Pokémon GO, which introduced many of us to augmented reality. We’ll point to Roblox, which showed us that we can participate in the creation of virtual worlds.

But there’s another, often-overlooked milestone, one that first onboarded millions to online interaction and digital economies: Neopets. Neopets, launched in 1999, was a place where people could raise digital pets and participate in a robust digital economy. It sounds simple (and a bit silly) but Neopets was a disarmingly complex world and a powerful force in shaping the internet’s evolution.

This week, I’ll look at five ways Neopets foreshadowed the consumer internet:

Neopets was the first social network, before social networks were a thing.

With that social network, Neopets introduced us to interest-based communities.

Neopets operated one of the first digital economies.

Through that digital economy, Neopets taught a generation how to be an investor.

And Neopets showed young people that they could help build virtual worlds, inspiring millions of future developers.

I’ll then step back to do a pulse check on where we’re at on the road to the metaverse.

Let’s jump in 🚀

Neopets: A Trip Down Memory Lane

In 1999, Neopets launched and gave us the fictional world of Neopia. Every webpage in Neopia was a different town, a place for “Neopians” to explore and play games and collect “neopoints”. You could then use your neopoints to feed and clothe your digital pet.

If you took care of your pet, it was happy. If you neglected it, it got sad. Neopets was one of the first examples of “return-to-manage” gaming: games with built-in incentives to keep players coming back. Future hits like Farmville and Clash of Clans would use the same model.

It worked. Two years after launch, Neopets had 14 million accounts, with the average user spending 117 minutes a week in Neopia. By 2005, the number of accounts had swelled to 92 million.

Nostalgic Millennials might remember playing endless hours of Ice Cream Machine or Cheat!, all so that we could earn enough neopoints to feed our JubJubs. The pets in Neopets were…odd. But we got to create them and name them, so they became an early form of online self-expression.

Neopets has a bizarre ownership history. Adam Powell and Donna Williams founded Neopets in 1999 (fun fact: the two would end up getting married in 2008) before selling a majority stake to an investor named Doug Dohring, who became CEO. Dohring later sold Neopets to Viacom in 2005 for $160M, which in turn sold the company (by this point a shadow of its former self) to JumpStart Games in 2014.

But let’s back up to Doug Dohring. When they sold to Dohring, Powell and Williams didn’t realize that Dohring was a Scientologist. Dohring began to inject Scientology education into Neopets, until the backlash was so severe that he was forced to stop. But he did base the Neopets business model off of the Scientology principle of “tiered experiences.” Neopets was the first example of “immersive advertising”—advertisements surreptitiously woven into the world of Neopia. A player might play a game featuring a character from a popular breakfast cereal, or stop by the McDonald’s shop or Disney theater.

The business model was controversial: parents and psychologists fretted that kids were too young to distinguish between content and ads. But in many ways, immersive advertising was the natural evolution of product placement in TV shows and movies; Neopets was just the first to do it.

Let’s dig into the five ways Neopets laid the groundwork for the consumer internet.

1️⃣ The OG Social Network

When Neopets launched, Mark Zuckerberg was 15. He wouldn’t create “The Facebook” in his Harvard dorm room for another five years. Myspace was still four years away. David Fincher’s film The Social Network was over a decade away.

Neopets was a social network before “social networks” were a thing. Forums, direct messages, and friend lists were key Neopets features. “Neoboards” were hubs of social activity, with conversation topics ranging far beyond Neopets-related subject matter.

Kids were thrilled to meet people online. Parents were terrified. For millions, Neopets was their first taste of the social internet.

2️⃣ Interest-Based Communities

Neopets was full of “guilds”—small, private groups of users built around shared interests. Because this was the early 2000s, Britney Spears and The Lord of the Rings were popular guilds.

Socializing on Neopets often meant being anonymous and connecting with strangers around the world. The social graph wasn’t yet tethered to our offline connections; people found each other based on interests, not geographic proximity.

In this way, Neopets shares more DNA with Discord and Reddit and TikTok—community-centric and interest-based internet destinations—than it does with Facebook, Snapchat, and Instagram in their original forms.

We’re now seeing a pendulum swing back to interest-based online connections, accelerated by AI’s ability to predict who we should interact with: ItsMe, Clubhouse, Lunchclub. While Britney Spears and The Lord of the Rings have given way to Billie Eilish and Marvel movies, the basic human behavior is the same: people forging relationships built on shared interest rather than on convenience.

3️⃣ In THIS (Digital) Economy??

For a virtual world most popular with middle-schoolers, Neopets had a surprisingly complicated (and realistic) economy. Users got bank accounts, where they could collect interest. They could invest their neopoints into Neopia’s stock market, called the NEODAQ.

Occasionally, developers would flood the site with neopoints and cause massive inflation. There was also rampant income inequality: a surprisingly academic article in The Neopian Times—yes, that’s Neopia’s newspaper—found that just 10% of Neopets users held over 50% of the wealth. (Ironically, this makes Neopia a far more equitable society than America.)

Participating in the economy was crucial. You had to make money—otherwise, you couldn’t feed your pet. A cheeseburger cost around 200 neopoints; rarer items might cost hundreds of thousands of points.

Naturally, a black market sprang up. Every Neopet had to have a unique name, but soon there were over 280 million pets. Pets named “Rex” were a lot more valuable than pets named “Rex472892pbn93w”, and they started getting traded off-platform for thousands of real-world dollars. Ebay eventually had to ban all digital Neopets assets.

While Neopets made its money from immersive advertising, its economy foreshadowed the rise of free-to-play gaming and in-game currencies. A decade ago, microtransactions made up 20% of gaming revenue; today, they make up 75%. By 2025, they’re expected to grow to 95%.

Roblox has Robux, Fortnite has V-Bucks, Minecraft has Minecoins. Emergent blockchain-based gaming platforms like The Sandbox, Decentraland, and Sorare have off-platform marketplaces for their digital assets that are eerily-similar to trading Neopets assets on Ebay.

Neopets kickstarted this phenomenon with one of the first digital economies. Many of the people selling cryptoart and gaming assets on OpenSea today were the kids selling rare Neopets dragon avatars on Ebay 20 years ago.

4️⃣ The Intelligent (12-Year-Old) Investor

In Neopets, you could actively participate in the NEODAQ stock market. You could buy shares in “companies”, and the performance of those shares was influenced by the Neopian economy. If you bought shares in Hubert’s Hot Dogs and more users bought digital hot dogs to feed their pets, your shares would go up in value. This, naturally, led to all sorts of bad behavior, as users coerced each other into juicing the shares of companies they held stock in. Insider trading was rampant.

Earlier this month, I wrote Everyone Is An Investor to examine how the younger generation learned to think like equity-owners. The Great Recession, Occupy Wall Street, and COVID all played a part. But so did Neopets. During the GameStop mania in March, Claire McNear at The Ringer wrote, “Two decades before Redditors waged war on Wall Street through the unlikely vessel of GameStop stock, the kids of Neopets happened upon a similar strategy.” Many of the people who today frequent r/WallStreetBets and boost the price of Dogecoin were once investors on the NEODAQ.

5️⃣ If You Build It, They Will Come

On Neopets, you could learn HTML to customize your own profile. Neopets even provided a simple guide to teach kids the basics:

This inspired a generation of developers. Especially female developers: 57% of Neopets users were female. One female software engineer remembers:

“I didn’t start coding because I thought it’d be a promising career. I just wanted to create something really cool, and on Neopets, you could do anything you wanted. From there I just started tinkering around and experimenting.”

Another, now working as a game designer, says:

“Neopets just literally introduced me to the concept of, ‘You can build a thing on the computer and it shows up on the screen.’ I had to be 12. I was really young.”

A generation later, Roblox would teach a new cohort of kids to build with software, again with an unusually-high number of female users and creators (online gaming tends to be male-dominating).

Most fundamentally, Neopets introduced the concept of user-generated content. In The Winding Tale of Neopets, Jay Hoffmann puts it best:

It shone a light on what the web could be like when we give up some control, when we let the people take over and create something truly unique. Turns out, they can build something pretty magnificent.

A Pulse Check on the Metaverse

Since the heyday of Neopets, internet usage has skyrocketed. American adults now spend over 11 hours interacting with digital media every day. That trajectory is reflected in the successors to Neopets: while users spent two hours per week in Neopets, the average Roblox daily active user spends 2.6 hours per day in Roblox. Fortnite has been collectively played for 10.4 million years—about 52x the time that humans have occupied the Earth. Digital worlds are consuming more and more of our time.

The technology underpinning these worlds is improving at a stunning rate. Here’s the progression of Lara Croft’s video game avatar from 1996 through 2018:

Epic’s Unreal Engine recently unveiled its MetaHuman Creator tool to create stunningly-realistic “digital humans.” These faces are synthetically-generated:

One of the most fascinating websites out there is thispersondoesnotexist.com. Every time you refresh the page, AI generates a new human face. Here are six of the faces that came up when I refreshed the site. None of these people are real.

This spring, Google previewed Project Starline, which creates three-dimensional video chatting “booths” that make it seem like you’re there in the room with someone else. In a touching video, Google invited family members to communicate across thousands of miles.

At the same time that technology is rapidly improving, human behavior is evolving to embrace digital interaction.

The pandemic was a key catalyst. Hours spent on Roblox soared, as more and more young people were introduced to immersive, self-built virtual worlds. (Roblox’s S-1 filing mentions the term “metaverse” 16 times.)

And Roblox, once a social network disguised as a gaming platform, is looking more and more like the new mold of consumer social. Lil Nas X, who I wrote about last week, held a concert in Roblox last fall that attracted 33 million users.

In the early days of the pandemic, Animal Crossing (perhaps the closest analog to Neopets in years) broke Nintendo’s first-year sales record. Executives even took business meetings in Animal Crossing; in this image, an executive has dinner with a client. (He brought her fish bait as a gift, a highly prized commodity in the game.)

COVID broadened the scope of digital worlds: they expanded beyond entertainment into work.

“Serious” things bled into the digital realm. Joe Biden and Kamala Harris put up yard signs in Iowa and in Animal Crossing.

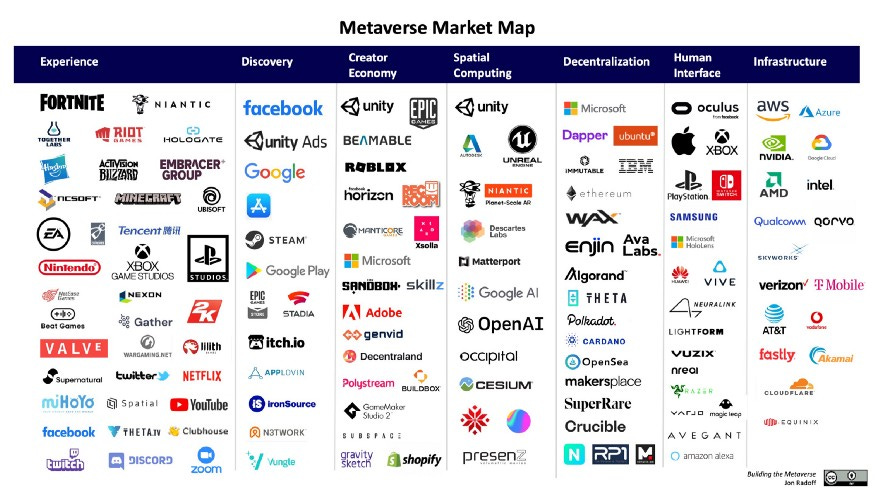

We’re at a unique moment in time: digital adoption is accelerating, enabled by both massive technological advancements and behavior shifts. Dozens of companies are helping to build the metaverse:

It’s most interesting to look back on how Neopets and the early internet era foreshadowed today’s consumer tech companies, and then ask the same questions about the next generation.

Looking at today, we can use the example of three companies in the Index portfolio:

Roblox stemmed from Neopets’ blend of gaming and social networking, as well as its customizability,

Discord was a natural extension of interest-based communities, and

Robinhood built upon the “everyone is an investor” thesis.

The same thought exercise can be applied looking forward. To reframe the five points from earlier:

It’s no longer groundbreaking to blur gaming and socializing; it’s tablestakes. But as the Roblox generation ages up, what is “Roblox for adults”? Is it something like Manticore Games, or is it something less obvious? Or does Roblox stay with Gen Zs as they transition into adulthood?

How does AI continue to reinvent interest-based communities? There’s no longer any reason that you need to see that girl from college who bullied you on your social feed, when there are seven billion people to draw from. Bytedance’s suite of AI-powered products is the most successful to date; what’s next?

How will digital economies continue to evolve, particularly new ones built on blockchain?

“Everyone is an investor” gave us Robinhood and Coinbase. What are the next iterations? Are they exchanges like FTX or social token networks like Rally?

On Neopets, users spent hours learning HTML so they could customize their profiles. People love expressing themselves. Myspace had that same inventiveness to its profiles, but Facebook stripped it away. What are the new ways people can use tech for self-expression online? And on the enterprise side, what will be the outcomes of more people being able to build with tech? We’ve seen companies like Notion, Airtable, Retool, and Bubble let anyone build with software legos, and that trend will only continue.

Final Thoughts

Today, Roblox occupies a unique place in culture: if you’re a kid or the parent of a kid, Roblox is likely a massive part of your life; if you don’t fit into one of those two groups, you’ve probably never heard of it. The same holds for Neopets—unless you were a young kid or the parent of a young kid in the early 2000s, it means nothing to you.

Every generation is introduced to technology in its own way. For older Millennials, it was a Tamagotchi. For younger Millennials, it was Neopets. For Gen Zs, it’s Roblox. Each is progressively more immersive, inventive, and customizable. Each brings us one step closer to the metaverse.

Of course, the metaverse isn’t something to “arrive” at—there’s no clear “Before Metaverse” and “After Metaverse.” Our lives will get progressively more digital, and the lines between physical and virtual will continue to blur.

But it’s clear that the pace of digital penetration is accelerating. Back in May, I wrote How People in the Philippines Are Making Money in the Metaverse about play-to-earn gaming, Axie Infinity, and Yield Guild. At that time, Axie was doing $3M in monthly revenue. Just 20 days into July, Axie has already pulled in $87M in revenue this month—a 2,800% increase from May. Trading volume is up 131x year-over-year.

Digital economies are growing faster than anyone expected. We’ve come a long way since Neopets, but we’re still in the early innings. One day—probably not too far down the road—the GDP of the digital economy will surpass the GDP of our physical world.

Sources & Additional Reading

Thank you to Dylan Field for inspiring this piece—and for reminding me of the hours I spent in Neopets, something I hadn’t thought of in years!

Looking Back at the Cursed and Controversial Legacy of Neopets | Manning Patson

How to Play Neopets | Thrillist

How Neopets Works | HowStuffWorks

Neopets Predicted GameStop | Claire McNear, The Ringer

The History of Neopets | History of the Web

If you’re looking for a longer read on the metaverse, Matthew Ball, one of my favorite writers on the topic, posted a 9-part series here: Metaverse Primer

Related Digital Native pieces:

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox each week: