How Startups Are Combatting America's Obesity Epidemic

The Tech-Powered Revolution in Health & Wellness

This is a weekly newsletter exploring the collision of technology and humanity. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

How Startups Are Combatting America's Obesity Epidemic

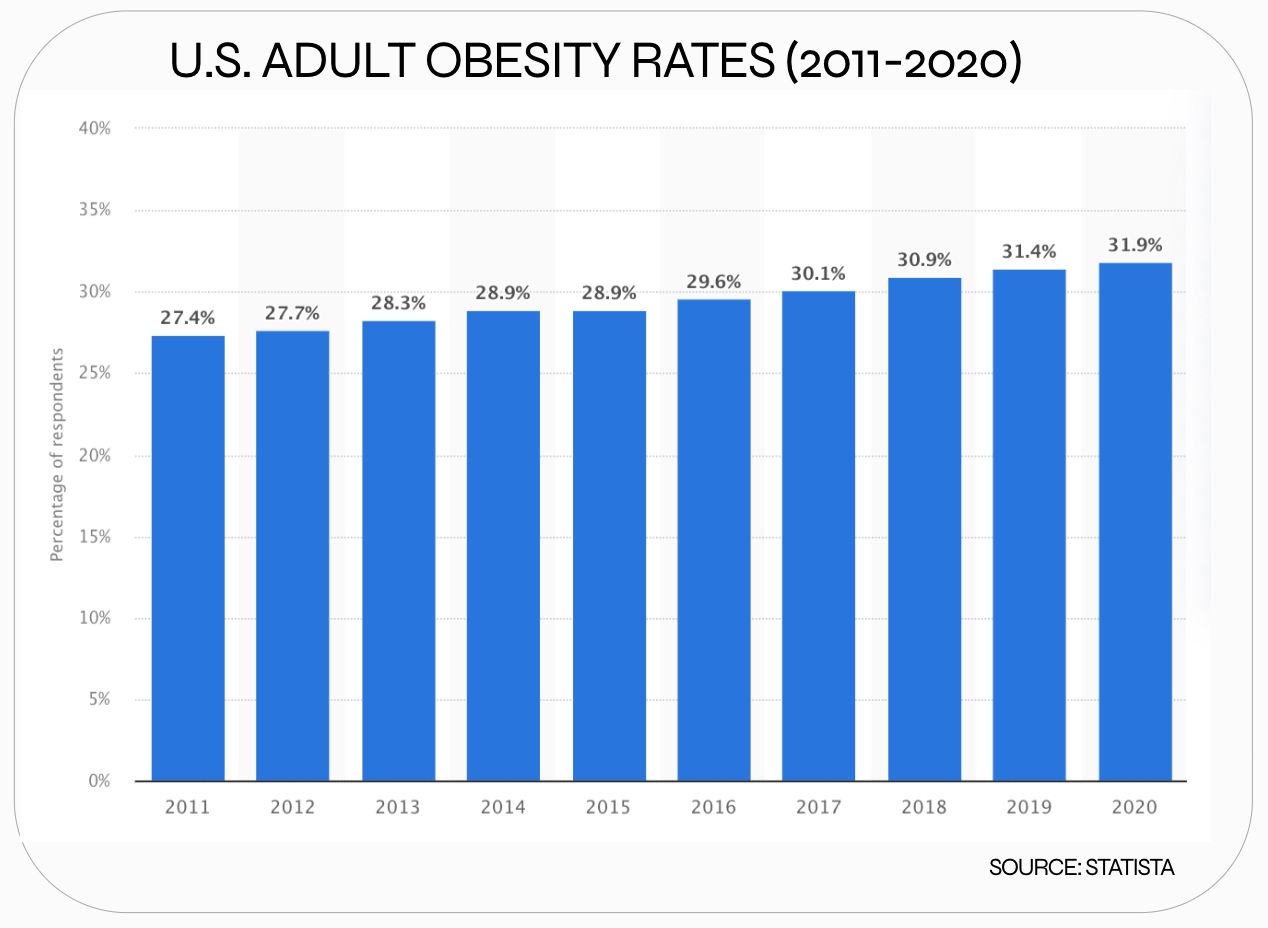

In 1990, zero states had obesity rates above 20%. In 2018, zero states had obesity rates below 20%.

I saw this graphic last week (courtesy of Turner Novak and Justin Mares), and I’ve been thinking about it ever since.

I had some idea of the root causes behind rising obesity rates—and some idea of what potential solutions might be—but I wanted to dig in deeper. That’s the goal this week. In tandem, I’ll look at how the startup ecosystem is combatting obesity. We hear a lot about “Health and Wellness” as an investment trend, but we don’t often hone in on specific companies that may have a chance to lessen the U.S.’s obesity crisis. Hopefully this piece begins to do so.

But first, some context setting.

Obesity Becomes an Epidemic

In 1997, the World Health Organization declared obesity a “global epidemic,” but it took until 1999 for America to really start paying attention. That year, several CDC-funded studies came out and immediately made clear how dire the situation had become. National alarm bells sounded, and policy gears began to shift.

But in Washington, things move slowly. It took years for meaningful political action to take place, and obesity rates have continued to creep up.

Obesity rates are also higher in communities of color, strongly correlated to socioeconomic status—we’ll talk about access to healthy food later. Black adults have the highest rate of obesity (49.9%), followed by Hispanic adults (45.6%), White adults (41.4%), and Asian adults (16.1%).

Today, obesity costs the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $173 billion a year. Obese adults pay $2,505 more in annual medical expenditures than people of normal weight.

Looking at the data, it’s easy to see when this problem began:

The chart begs the question: what happened in 1980?

Most people are able to conclude that obesity is a factor of two primary inputs: (1) diet, and (2) exercise. Calories in, calories out. But one of these two potential culprits has been proven much more important. Nearly all of the obesity epidemic can be traced to America’s diet.

Here’s a chart of total calories in the food supply per capita (i.e., how many calories your average American eats per day); the chart is strongly correlated with the rise in obesity rates, both inflecting around 1980.

Researchers have similarly worked to isolate the effects of reduced physical activity, but have found no strong correlation. From a paper by David Cutler, Edward Glaeser, and Jesse Shapiro:

Between 1910 and 1970, the share of people employed in jobs that are highly active like farm workers and laborers fell from 68% to 49%. Since then, the change has been more modest. Between 1980 and 1990, the share of the population in highly active jobs declined by a mere 3 percentage points, from 45% to 42%. Occupation changes are not a major cause of the recent increase in obesity.

Changes in transportation to work are another possible source of reduced energy expenditure—driving a car instead of walking or using public transportation. Over the longer time period, cars have replaced walking and public transportation as a means of commuting. But this change had largely run its course by 1980. In 1980, 84% of people drove to work, 6% walked, and 6% used public transportation. In 2000, 87% drove to work, 3% walked, and 5% used public transportation. Changes of this minor magnitude are much too small to explain the trend in obesity.

In short, by 1980 we were already a quite sedentary population, yet obesity rates had yet to skyrocket. (Other explainers like the onset of the internet and video games also don’t work, as those didn’t take off until the 90s.)

The clear culprit is our diets. As a result, I’d argue that Michelle Obama’s 2009 Let’s Move! campaign (which focused on childhood obesity) was poorly named. The movement should have been less about increasing physical activity, and more about healthier eating. But I mean no offense to Ms. Obama—Let’s Move! was both a pivotal piece of policy during her husband’s administration and a meaningful driver of public awareness, buoyed by her persona.

Let’s Move! had five key focuses for tackling obesity: (1) Early childhood, (2) Empowering parents and caregivers, (3) Healthy food in schools, (4) Access to healthy food, and (5) Increasing physical activity.

I’ll use an adapted version of those five to frame this piece. These apply more broadly to both the U.S. population (adults and children alike), and to how the startup ecosystem is innovating our way out of this epidemic:

Nutrition

Pediatrics

Access to Healthy Food

Fitness & Wearables

Weight Loss

First up, nutrition.

1) Nutrition

Remember the Food Pyramid? For any Millennial, the Food Pyramid was a staple of childhood: the reminder of faded plastic posters on your school cafeteria wall may even give off a whiff of nostalgia.

The Food Pyramid was introduced by the United States Department of Agriculture in 1992. The problem? It was totally wrong. Studies over the years have proven that the pyramid was strongly influenced by food manufacturers, food producers, and special interest groups. Taking one look at the diagram, it’s clear that the grain lobby (Big Grain?) played a major role.

The USDA recommended 6-11 servings of carb-heavy grains, yet only 3-5 servings of vegetables and 2-4 servings of fruit. The pyramid—and government policy throughout the 80s and 90s—treated fat as Public Enemy No. 1, while largely turning a blind eye to the detriments of sugar. Dr. Robert Lustig, a pediatric endocrinologist, says: “This advice to eat more carbs and avoid fat is exactly backwards if you want to improve health and lower body weight.”

Clearly, misguided nutritional information is a key cause of the obesity epidemic. Justin Mares, a health food entrepreneur, shared a few other examples of how messed up America’s diet and nutrition culture are:

Soda companies spend 11x more on nutrition studies than the National Institute of Health. 82% percent of independently-funded studies show harm from sugar-sweetened beverages, but 93% of industry-sponsored studies said no harm. Weird how that works out… 🤔

95% of the panel who created the most recent nutrition guidelines had financial ties to food or pharmaceutical companies.

In 1963, the Sugar Research Foundation (SRF) paid Harvard researchers the equivalent of $50K to refute sugar’s role in heart disease, and researchers happily produced the results they were hired to produce. Instead of blaming sugar, Harvard and the SRF blamed cholesterol and saturated fat. Today, after 60 years of fat-is-bad food policy, Americans have never been in worse health, with no shortage of studies vindicating fat—including saturated fat.

80% of American subsidies go to corn, grains, and soy oil. Amazingly, cigarettes (tobacco) receive four times more government subsidies (2%) than all fruits and vegetables combined (0.45%).

Justin also shares this comparison with Europe, which emphasizes that this is a uniquely American problem:

And as one final example, here are the ingredients of Ritz Crackers in the U.S. versus in the U.K. 😬

What’s the solution here?

In short: more affordable, more accessible, higher-quality nutritional info.

One startup that I find compelling (and that I’ve personally tried out) is Nourish. Nourish is a marketplace connecting consumers to registered dietitians for personalized nutrition counseling. Crucially, Nourish helps you get these sessions covered by your insurance.

In my initial session, I chatted over Zoom with a dietitian based in Ohio. She asked me about my personal relationship with food and my typical diet, and we explored ways that I can tweak my habits to be more healthy—particularly given my family history of diabetes. (One note on the difference between dietitians and nutritionists: dietitians are certified to treat clinical conditions, like diabetes and heart disease, whereas nutritionists aren’t always certified.)

In many ways, Nourish’s business model is similar to that of mental health marketplaces like Headway and SonderMind, which offer both discovery for people looking for a therapist, and vertical software to facilitate a therapist running her business. A core tenet of both models is enabling insurance to cover treatment at scale.

The hope is that technology can better connect those with valuable nutritional knowledge to those who need it—and if insurance steps up, that access can be granted even to the lower-income populations most at risk of becoming obese.

2) Pediatrics

Among those who need that nutritional guidance most: kids.

Habits form young, and childhood obesity is itself an epidemic. Obesity rates are rising among kids and adolescents, reaching nearly 20% of the population among those ages 2 to 19. Those rates have more than tripled since the 70s, and again, Black and Latino youth have substantially higher rates of obesity than their white peers.

New York City has been among the most forward-thinking cities when it comes to childhood obesity. In 2007, the city instituted a new policy targeting childcare centers. The policy eliminated TV and videos for children under 2; limited viewing for children older than 2 to 60 minutes per day of educational programs; required 60 minutes of physical activity daily; eliminated sugar-sweetened beverages; ensured the availability of water at all meals; and mandated the use of 1% or skim milk. The program was shown to have 75%+ adherence to the diet and physical activity requirements, though changes in obesity couldn’t be measured because baseline BMI data hadn’t been collected.

That program became the blueprint for much of national policy and, later, for the Obama Administration’s efforts under the 2009 Let’s Move! campaign.

Yet the success of national policies—including Let’s Move!—has been mixed, and obesity rates among kids have risen from ~18% in 2009 to ~20% today.

As a result, the American Academy of Pediatrics recently came out with new guidance on childhood obesity—the first in 15 years—that recommends moving away from “watchful waiting” (delaying treatment to see if children outgrow obesity) and instead offering more intensive treatment options earlier, such as therapy and medication. Companies like Nourish could again facilitate counseling and therapy, as needed.

Another startup that could play a role: Summer Health. Summer Health is a text-based telehealth platform focused on pediatric care. You pay $20 / month and are guaranteed to get text responses from certified pediatricians within 15 minutes. The average parent visits their pediatrician 10 times a year during the child’s first two years, and four times a year thereafter—and that’s despite often long wait times.

Summer’s founder, Ellen DaSilva, came up with the idea when her newborn had a health issue in the middle of the night and she couldn’t reach her pediatrician. Her company’s mission is to broaden access to pediatric care—and obesity is a piece of that care. Better access and better care will be essential to combatting obesity early.

3) Making Healthy Food More Accessible

Unhealthy food is less expensive than healthy food—about $550 less per person per year, according to the latest studies, which adds up quickly for a large family. As a result, eating healthy is often cost-prohibitive.

Eating healthy is also often geographically unfeasible: 23.5 million Americans live in “food deserts,” defined as places where a supermarket is more than one mile away in an urban location or more than 10 miles away in a rural location. (54 million Americans, meanwhile, or 1 in 6 people, are “food insecure,” which occurs when food is either too far away or too expensive.)

Fixing the problem will ultimately come down to better policy—and because policy is imperfect and slow-moving, food insecurity will never go away completely. But while policy is essential, the private sector can also step up to ameliorate some of the problem.

Misfits Market and Imperfect Foods, for instance, offer grocery delivery at greatly-reduced prices, focusing on healthier foods that have often gone unsold or were deemed unfit for the grocery store. Imperfect Foods, for instance, got its start as Imperfect Produce, selling misshapen and blemished fruits and vegetables 🥕 Both startups help eliminate food waste while improving access to healthy foods.

Too Good to Go, meanwhile, is a marketplace for surplus food that got its start with restaurants. About a third of food goes to waste, and the company wants to change that. With the marketplace, restaurants can get rid of excess food in Too Good to Go meals at the end of the day; consumers, meanwhile, can get access to more affordable and high-quality meals. Too Good to Go has since expanded beyond restaurants to shops, schools, and other venues that sell food. The website touts that 70.6 million people have found food through the marketplace, while 179K businesses have reduced their food waste.

A final example is Shef, which is a marketplace for home-cooked meals. A few years ago, laws began to allow people to sell meals out of their homes. Shef was born as a marketplace to connect these home chefs with consumers. Home-cooked meals are often much healthier than fast-food or restaurant alternatives, meaning that Shef crowds in more choice for the consumer seeking more nutritious meals.

Startups can only do so much, and they’re no substitute for top-down national policy to subsidize healthy foods and to build more grocery stores in food deserts. But they can make meaningful differences with clever business models that align incentives for chefs/restaurants/businesses (no one wants to lose money on food waste!) and they can ultimately bring healthier food into people’s hands.

4) Fitness & Wearables

Though fitness is proven to have less of an impact on the obesity epidemic, it still plays a key role in health and wellness. From an investing standpoint, fitness is traditionally a tough category: churn is typically very high. (Companies like Peloton are an exception, because churning is tougher when you’ve plunked down $2,000 for a bike.) It turns out that many people simply…don’t like to work out. And it’s a lot easier to sell sins than virtues; it’s hard to pay for things we don’t like doing.

But that hasn’t stopped an explosion of fitness companies. There are hardware companies like Tonal, Mirror, and Tempo; social networks like Strava; and coaching platforms like Future and Playbook.

One related category is wearables, which often go broader than fitness into health-monitoring writ large. The Apple Watch is the giant in the space (it accounts for 3 in 10 smartwatches sold, and passed the 100M units mark in December 2020, 5.5 years after its April 2015 launch), but there are other promising companies: Oura, Whoop, even the Eight Sleep mattress. There are clearly major tailwinds behind consumers paying more attention to (and spending more money on) their overall health and wellness.

5) Weight Loss

The award for worst rebrand of the past few years has to go to Kia 🏆 Google searches for “KN car” have skyrocketed since Kia redid their logo.

But a contender for second place? WeightWatchers’s rebrand to WW in 2018. You might think that the WW stands for WeightWatchers. You’d be wrong. WW stands for “Wellness That Works” and the brand’s reasoning behind the name-change was that “weight” had becoming a triggering and judgmental word.

The problem was two-fold. First, it became clear that WeightWatchers’s core customers actually liked the word “weight.” They were, after all, trying to lose weight. They were offended by the rebrand, and it’s never good when you offend your best customers. Second, WeightWatchers WW erased 55 years of hard-earned brand building, becoming unrecognizable and essentially starting from scratch.

The bottom line is, weight is directly tied to health. Yes, weight can be a touchy subject—but obesity is a major risk factor for diabetes, heart disease, and some cancers. Maintaining a healthy weight is critical for long-term health.

As a result (and because our society glorifies being thin), 50% of Millennials report losing weight as one of their New Year’s resolutions. Interestingly, the share among Gen Zs is just 27%. Part of that is likely because Gen Zs are younger and weight gain hasn’t yet caught up to them with age. But part likely stems from a societal shift toward body positivity and the rebranding of diet culture. Younger Americans are more likely to make resolutions around healthier eating and exercise compared to older Americans. Inputs, rather than outputs.

That said, weight loss companies are still large businesses. WeightWatchers/WW has been around nearly six decades. Newer companies include Noom, Calibrate, and Found. Like fitness, weight loss can be a tough category. After all, success means automatic churn (the dating app market has a similar dynamic). And with so many players in the space, differentiation can be weak and companies can quickly become paid marketing-driven. But that isn’t to say the unit economics don’t always work: LTV for weight loss can be big; Noom’s annual plan bills upfront at $209.

This piece so far has glossed over the fact that much of obesity is genetic: most studies estimate about 40-50% of variability in body weight can be traced to genes. Sometimes, despite healthy eating and ample physical activity, there’s not much you can do.

The big news in recent years has been the rise of Ozempic and Wegovy, controversial but purportedly highly-effective weight-loss drugs. Last year, there was speculation that Kim Kardashian used Ozempic to fit into Marilyn Monroe’s dress at the Met Gala. Headlines have declared the drugs “Hollywood’s weight loss secret” and people have scrambled to get their hands on them. But the drugs can take a toll on you: The Cut’s piece You May Go Through Hell for Your Post-Ozempic Body is chilling.

That said, for many people, weight loss drugs may be the best option. Recent guidance from the American Academy of Pediatrics suggested that drugs should be considered for adolescents as young as 12. Wegovy has been shown to help adolescents reduce their BMI by about 16%, but the drug faces major shortages and many insurance companies decline to cover it.

Drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy are still relatively new, and there’s a lot to figure out. I’m no expert on their efficacy or side effects. But in the face of a worsening obesity epidemic, they may be a piece of the eventual solution.

Final Thoughts

Clearly, combatting obesity still has a long way to go: we’re heading in the wrong direction, and policies either aren’t working or aren’t working well enough.

Researchers have found that in contrast to other social movements, the response to obesity has been top-down vs. bottom-up. While movements such as civil rights, tobacco use, and seatbelt use relied on grassroots efforts, the obesity movement has relied on government policy. Researchers conclude, “The response to obesity may not be sustainable unless it generates a greater level of spontaneous community engagement.”

The good news: nothing does community engagement as well as the internet. Technology has the ability to spread quality nutritional information; to destigmatize asking for help; and to drive compounding, community-led efforts to improve national health. The new KPI is BMI. Many of the startups here are leading the charge, and many others are just getting started.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Next, Episode 38 | Justin Mares

Why the Surge in Obesity? | Lane Kenworthy

Why Have Americans Become More Obese? | Cutler, Glaeser, Shapiro

CDC, FDA, USDA data

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: