How to Build Your Startup Brand

How Red Antler designed brands like Chime, Ramp, and Allbirds

Weekly writing about how technology shapes humanity, and vice versa. If you haven’t subscribed, join 45,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

How to Build Your Startup Brand

I’ve always been obsessed with brand. Brand is something intangible, squishy, hard to pin down. But it’s essential to a company’s success. We wear Nikes because we want to be like LeBron and Serena; we watch Disney movies because Disney embodies great storytelling; we buy Apple products because Apple stands for innovation and product excellence.

There’s a classic debate in the startup world over whether brand is a moat. In other words, can a company’s competitive differentiation come from its brand? My view has always been yes. There are better moats than brand, sure, but brand matters. Many iconic companies (both consumer and enterprise) will always enjoy an advantage because of the strength of their brands—and that advantage compounds, with the strongest brands enjoying name recognition that drives strong cash flows, which can then be plowed back into further growing the brand.

In the long history of commerce, brand is a relatively recent concept. Marketing, in its modern form, essentially didn’t exist before the Industrial Revolution. There was such little product differentiation that it wasn’t necessary. Then manufacturing exploded, and production became cheaper and faster than ever before. New entrants crowded the market, and marketing became essential. Today, marketing is often all that distinguishes a product. And as generative AI further opens the floodgates of production—a digital revolution akin to the physical world’s Industrial Revolution—brand will be an even more important differentiator.

Marketing rules our consumerist society. Children as young as two can recognize brands on shelves, and by age 10 children have recognition of 300 to 400 brands. Iconic companies ranging from Amazon to Coca-Cola built empires on the backs of their brands. The power of brand is clear.

To geek out about brands in the startup context, I sat down with the team at Red Antler. Red Antler is the brand agency behind some of the best startup brands of the past decade: Chime and Ramp, Allbirds and Casper, Opendoor and Hinge. I chatted with Emily Heyward, Co-Founder and Chief Brand Officer, and Jenna Navitsky, Chief Creative Officer, about why brand matters.

This week’s Digital Native piece unpacks our conversation, including specific stories of brands Red Antler has helped create (for example, how they named Allbirds and Chime), as well as tactical advice for designing a brand from scratch. We’ll cover:

What Is A Brand?

How to Name a Company

Case Study: Chime 💰

Case Study: Allbirds 👟

Defining a Brand Strategy

Case Study: Casper 🛏

Case Study: Ramp 💳

You Have a Brand. Now What?

Revamping a Stale Brand

Case Study: Hinge 💏

Final Thoughts

Let’s dive in.

What Is a Brand?

A brand is a crystal clear definition of why your business matters. Why should people choose you? This question becomes even more pressing in a world of near-infinite choice: when there are so many options out there, why you?

Emily and Jenna emphasize that your brand is not your name, your logo, or your color palette. Yes, each of those is an element of your brand, but brand is something bigger. Think about a coffee shop that you love. You love the ambiance in the room, the aromas, the way the barista greets you by name. That’s the brand. It’s how the entire experience makes you feel. The logo on the coffee cup is part of it, yes, but only one small part of it. (This example can extend to Starbucks, one of the world’s most iconic brands: the actual coffee and the mermaid logo are aspects of the Starbucks brand, but the brand extends to how the coffeeshop feels, how the baristas writes your name on your cup, and the ease, convenience, and reliability that Starbucks represents.)

Ideally, brand ladders up to something bigger: why does this business matter? Brand strategy and business model should go hand-in-hand. More on that in a bit.

How to Name a Company

Before diving into brand strategy, let’s talk naming. This is often the first step in defining a company’s brand.

I asked Emily and Jenna how they go about naming a company. Their first response: you can sit in a room and come up with the ideas, but the biggest barrier is actually trademark availability. You need to come up with a lot of ideas to vet; once your trademark search is done, you might be left with only a handful of options.

They also emphasize that the strongest names are very rarely literal. In fact, literal names can be constraining. OpenTable and MailChimp were names based on a feature that ended up being limiting to the company in the long run. The best names create a feeling, and aren’t trying to do the job of explaining what the business does. Good advertising can take care of that.

I asked Emily and Jenna to give me a recent example of a name they came up with. Ourself is a skincare brand that focuses on high-end skincare and anti-aging. The name doesn’t tell you what the products do, but rather evokes a general feeling of optimism and self-love that aligns with the company’s mission. (It’s also a net-new word, which helps with trademarking and SEO/SEM.)

When I ask Emily and Jenna what to avoid when naming a company, they give me a few rules of thumb:

Any ridiculous spelling—names should be phonetic. Customers shouldn’t have to struggle to find or spell something.

Anything gimmicky—for instance, the late 2000s trend of removing a vowel (Flickr, Tumblr, etc). These trends become dated quickly.

Anything silly or startupy—for instance, the company Hooli from the show Silicon Valley, which sounds straight out of…well, Silicon Valley.

Another name I like in the Red Antler portfolio: Backbone. Backbone is a gaming company that makes a mobile controller that turns your phone into a powerful gaming device. It’s one of my favorite companies in the gaming space, combining hardware with a platform that powers core gaming and cloud game streaming on mobile.

Backbone already had its name when it came to work with Red Antler, but the name is uniquely strong. The device structurally acts like a backbone to your phone: you plug in to the phone’s accessory port, and the controller turns your phone into a powerful gaming device on par with high-end consoles. The name is clever, and it works visually. But the name also has a strong alliterative sound, and it exists in the gaming space without overused words like “game” or “play” in the name.

Case Study: Chime

When Chime came to Red Antler, the business was called Qoin (pronounced “Coin”—breaking the rule of weird spelling and phonetic names). The Red Antler team knew they wanted a name that felt simple, easy, and optimistic. Chime—which now counts 14.5M users, with 9M using Chime as their primary bank—initially focused on helping people who had a debit card get the same types of rewards only available to credit card holders. As a result, Chime was going after a lower income-bracket: people not eligible for credit cards.

The name needed to evoke positivity. The word “chime” makes you feel good. It alludes to the ding of a reward, and has a unique and memorable sound to it. It has the added benefit of not being a literal name, which gave the Chime team flexibility to move in new directions and launch new products.

Case Study: Allbirds

Red Antler started working with Allbirds pre-launch, when the company had just run a Kickstarter under the name Three Over Seven. The first step was to find a better name, and the Red Antler team worked closely with the founders on the process.

Allbirds is a mission-driven company, launched with the goal of embedding sustainability into footwear and rethinking supply chain. But the team knew they wanted to be bigger than just the environmental shoe. They had to build a brand that captured people’s imagination. This was especially true because they’d be competing in footwear, a category where brand has become essential. (As Emily puts it: “If you ask people their favorite brand, they will say Apple or Nike. You’re competing with a juggernaut, and Nike taught people to expect an emotional connection to their footwear.”)

In one creative session, the Allbirds founders and Red Antler team were talking about New Zealand (where the founders are from) and the Kiwi, the country’s national bird. Someone said, “You know, before humans got to New Zealand, it was all birds.” Everyone began to picture a continent filled with only birds, and felt the visual captured the company’s environmental roots. It also evoked travel, nature, and adventure. They trademarked the name Allbirds and that was that.

Defining Your Brand Strategy

The first tactical step to building a brand is defining a brand strategy. This is a short, crisp statement about what your business stands for. The brand strategy isn’t the same thing as the mission statement. For example, Apple’s mission statement used to be “Have a computer in every home in America,” while it’s brand strategy centered on innovation and creativity. The mission statement tends to skew internal, while the brand strategy skews external.

An example on brand strategy from Red Antler: Sheertex is a company that makes tights that don’t rip. The functional description is just that: tights that don’t rip. But the brand strategy is different: guaranteed good luck. This strategy came out of the idea that women tend to wear tights when they want to look polished and dressed up; a snag ruins your confidence. Sheertex lets you move through the world with good luck, feeling unstoppable.

The brand strategy should ideally be derived from the business model.

As an example, Airbnb built one of the most iconic brands of the past decade on its brand strategy of “Belong Anywhere.” That strategy captures the feeling that everyone wants to have when they travel and is directly connected to Airbnb’s mission. The brand strategy isn’t “cheaper than a hotel” or “has a kitchen.” The strategy transcends functional descriptors to tap into the emotional appeal of the product.

As Emily points out, Airbnb can deliver on this brand strategy because they enable travel experiences that are different than staying in a hotel. Hilton couldn’t own “Belong Anywhere” in the same way; the brand strategy doesn’t align to its product nor its business model.

Case Study: Casper

When Casper was created, no one loved their mattress brand. The Red Antler team wanted to change that. They crafted a brand strategy that wasn’t about memory foam or a cheaper mattress; it was about better sleep leading to a more interesting life.

The result was that Casper became a household name and created a new category—that of the DTC mattress brand.

Case Study: Ramp

When Red Antler began working with Ramp, Ramp was looking to disrupt the corporate card market. The corporate card world is dominated by established players that are associated with status (cough, Amex, cough). Ramp needed to do something different.

Ramp’s strategy became, “Smart is the new platinum.” The founders and Red Antler realized that today’s businesspeople are less concerned with dropping the corporate card at the steak lunch, and more concerned with visibility, control, and data. They want to spend less and they want to spend more intelligently. Flagrant spending is out; smart, sustainable growth is in. Ramp’s brand strategy leaned into these insights.

Ramp’s brand strategy came from a long discovery phase: talking to the founders, conducting primary consumer research, studying trends, analyzing competitors. The key was to hone in on what’s happening in the world, and what the customer wants. Not what the customer expects, but what the customer wants. The Ramp and Red Antler teams realized that people expect a financial services company to look and feel a certain way, and they wanted to do away with that. From Jenna: “Unsexy categories are the biggest opportunity to do something really interesting.”

(One side note: brand is incredibly important in B2B. Most industries are seeing a consumerization, and most of the products used in enterprises are chosen by workers. Ramp is an example here, as well as prosumer tools like Slack, Figma, and Notion. Even data and infrastructure companies need brands—someone is choosing to go with AWS. At the end of the day, human beings are making the decisions, and humans are influenced by brand.)

You Have a Brand. Now What?

After defining a brand strategy come the other elements of brand: logo, tone of voice, aesthetic feel. Next come tactical nuts and bolts: website, social strategy, real-world physical advertising (think Casper papering the New York subway, or Chime putting up billboards around San Francisco).

Emily and Jenna are clear about two things:

How we define brands has stayed similar,

But where brands need to show up has changed dramatically.

Brands need to show up more often and more consistently. Brands fall apart when they stay in the realm of the abstract and fail to the translate into a real-world applicable toolkit.

A misconception of brand is that brand is the logo, typeface, color palette. Those are the foundational elements, but brand continues after those are in place. The next step is to bring the brand to life through savvy marketing and advertising.

Other misconceptions:

Thinking a logo is the same as a brand

Thinking brand is just about a nicely-designed website (important but tablestakes)

Thinking that brand is an exercise in color palettes (lots of clients say, “I want to look like a Gen Z brand” without realizing those colors are just another trend that will soon fade; brand goes far beyond Gen Z colors)

One question Red Antler gets often is, “Should we go in-house or use an agency?” The team’s view is that there comes a point when some internal capability is necessary, and that timing varies dependent on your business: if you’re launching a creative brand, you need a creative director at launch; if you’re launching B2B software, you can rely on a talented branding partner and hire a more junior designer to make sure the assets you have maintain the brand. But a third-party can help pressure test ideas and hold you intellectually honest.

Brand isn’t “set it and forget it,” though it also doesn’t mean rebranding every six months. You do have to continue to tell your story in ways that keep people interested. This is particularly true with existing customers. You can’t build a business on acquisition; you have to build it on retention as well. In Emily’s words, “People forget that existing customers are your most important audience.”

The best brands find ways to continue to build affinity with customers. One of my favorite examples is Chewy, the e-commerce pet company ($16.4B market cap). If a customer calls to cancel an order because their pet died, Chewy sends that customer a sympathy card and flowers. Chewy also sends customers birthday cards, anniversary cards, and even free paintings of their pets.

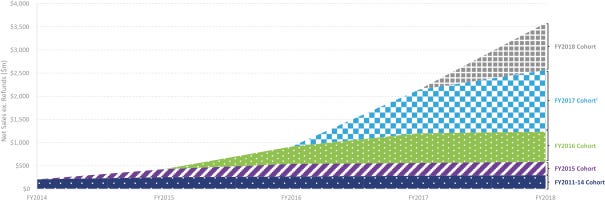

This focus on existing customers shows up in Chewy’s business: cohorts spend more with Chewy as time goes on. In Chewy’s S-1 filing, it noted that its 2015 cohort—customers who first signed up for Chewy in 2015—had nearly doubled their annual spend three years later.

Even if Chewy never acquired another single customer, it would still see healthy growth from its existing customer base. Strong net dollar retention stems from strong customer support, which itself stems from a brand strategy built around deep customer relationships.

Revamping a Stale Brand

New companies need to craft a brand. But occasionally, older brands become stale and need a refresh.

This is when an agency might help: it’s hard to do the foundational work yourself, and an outside thought partner can make sure you’re not trying to be too much to too many people.

One example comes with how Red Antler revamped the dating app Hinge.

Case Study: Hinge

When Tinder launched, Hinge launched right on its heels. Overnight, everything became about the apps. Hinge’s old logo was a literal hinge (Emily: “It couldn’t have been less romantic”) and the app was struggling to break free from a crowded pack of dating apps. The company hired Red Antler for a revamp.

Red Antler’s consumer research revealed that there was a growing backlash to dating apps—people were sick of endless swiping. The team knew that Hinge needed to be about something more. They asked, “Can Hinge credibly be the app that’s about finding a real connection?” If Tinder is about ease of connection, this is the app for something real.

To the Hinge team’s credit, they realized they couldn’t own this strategy with the current product. So they paused the brand revamp and rebuilt the Hinge product to focus on profiles, not on swiping. They knew they needed a product that could support the new strategy.

Once the team was ready, Red Antler got to work. They relaunched Hinge as the relationship app, and came up with the brilliant “Designed to be deleted” campaign. That campaign came out of the insight that the new dating milestone was when you delete the apps together. The purpose isn’t to keep you on Hinge, playing games for months; it’s to get you off the app.

That campaign was explosive, and Hinge is now vying with Tinder and Bumble for the top slot in dating apps. (The video for the ad campaign has 2M+ views on YouTube and is hilarious.) The revamp was a combination of product and brand, with the two working in concert to reinvent a stale company.

Final Thoughts: “Brand is an investment, not a cost.”

When I ask Emily and Jenna what Gen Z cares about, they don’t hesitate: “The days of presenting a perfectly-polished, controlled, consistent image are over,” Jenna says. Young people want to be in conversation with brands, and feel part of the story. People want the behind-the-scenes, the messiness. This is clear in savvy strategies like the unhinged Wendy’s Twitter, or Duolingo’s twerking-heavy TikTok (see: How Duolingo Grew Its TikTok to 6.6M Followers).

This is directly a result of growing up online. Emily notes that people don’t want to see models; they want to see real people. For a while, she says, people said they wanted to see real people but the data didn’t support it; ads with models outperformed. That’s no longer the case. Authenticity, the overused buzzword, is in vogue; people rebel from the airbrushed, overly-curated brand strategy. We see this in the fall of companies like Victoria’s Secret and the rise of companies like ThirdLove.

One final point: brand is equally important for recruiting.

Red Antler works with a company called Archer that’s building flying cars. The product is 10 years out, so what’s the point of a brand? In short, to attract top talent. The best engineers want to work at companies with well-designed, thoughtfully-crafted brands. Brand becomes a magnet for talent. The same is true for investors; whether we like to admit it or not, a good brand helps in the fundraising process.

As Emily puts it, “Brand is an investment, not a cost.” Brand is more than your name, logo, typeface, and color palette. It’s emotional, tapping into how you meet the needs of your customer. If you spend the time to get it right, it makes everything else easier—from performance marketing to hiring to fundraising.

Sources & Additional Reading

Thank you to Emily Heyward and Jenna Navitsky for sitting down with me to geek out about brand and share how Red Antler approaches brand strategy

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: