How to Monetize Culture

The Future Business Models of the Internet

This is a weekly newsletter about how people and technology intersect. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

How to Monetize Culture

The top-earning YouTuber for the last three years running is a 9-year-old boy. His name is Ryan Kaji, he lives in Texas, and he took home $30 million last year.

With 29 million subscribers, Ryan has one of the most-popular YouTube channels in the world: on his main channel, people watch 1 million hours of video every day.

But Ryan has also expanded well beyond YouTube. Ryan and his family have worked with PocketWatch, a content studio and accelerator for kid stars, to build an empire that includes his own product line, over 100 licensing deals, and merchandising deals with both Walmart and Target. I read a good profile of Ryan in Bloomberg over the weekend and found one part particularly interesting (in bold):

In total, products bearing Ryan’s World branding generated more than $250 million in sales in 2020, according to Chris Williams, whose company PocketWatch handles the family’s licensing business outside YouTube. The Kajis’ share of those sales represented from 60% to 70% of the $30 million of their annual revenue—making it the first year their licensing business has surpassed their YouTube ad revenue.

Ryan’s income is shifting from advertising to commerce, embodying a broader shift happening across the internet. Ad revenue often isn’t enough to support creators, who are the lifeblood of the internet. One study found that reaching the top 3.5% of YouTube channels—which means about 1 million views each month—only gets you $12,000 to $16,000 a year. That’s right around the federal poverty line. About 97% of YouTube creators aren’t making minimum wage from YouTube. One popular YouTuber, Shelby Church, wrote a blog post about how getting 3,907,000 views on a video only made her $1,276.

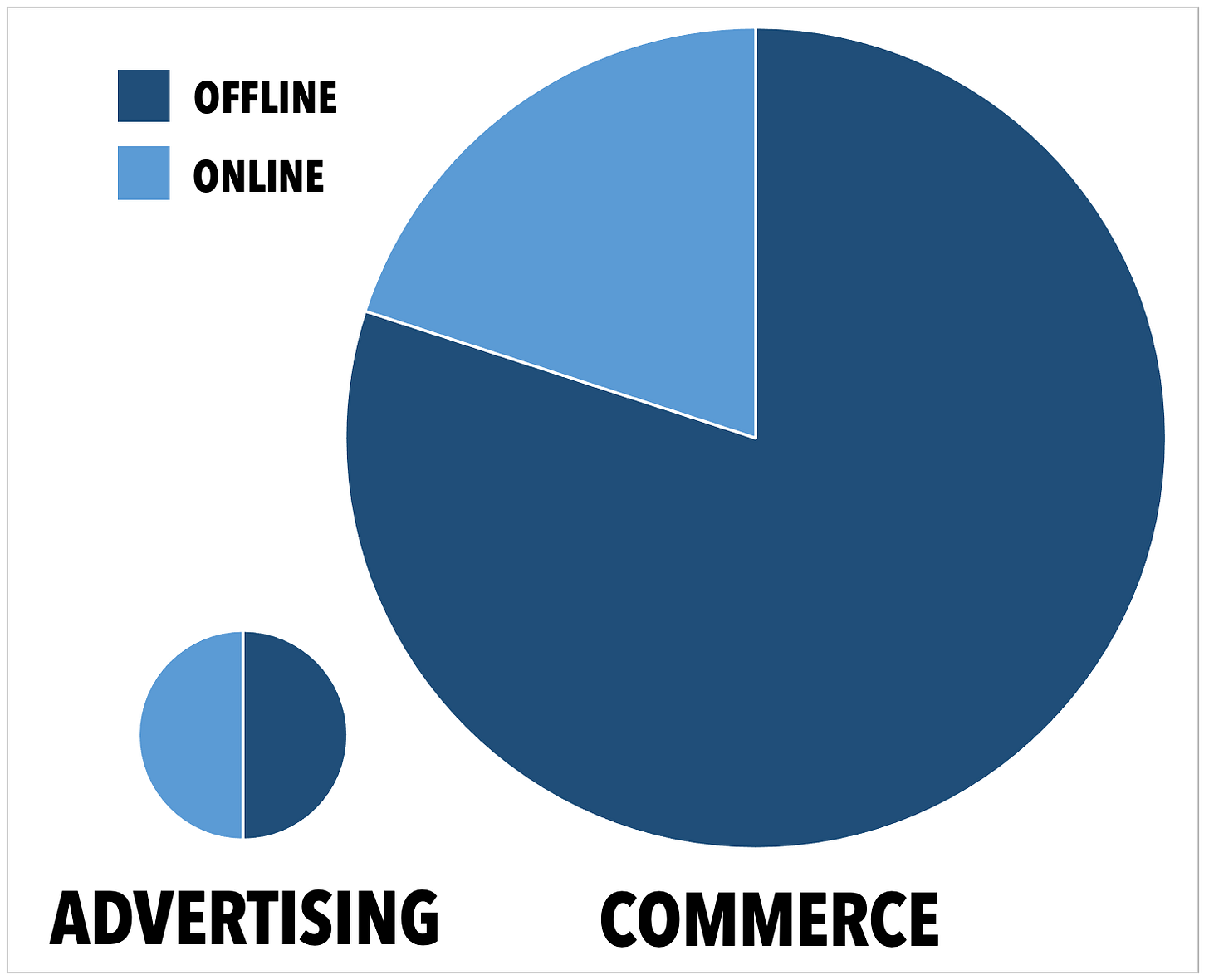

Advertising also has less room to run. The global advertising market was $647 billion in 2020, about 50% of which is already online. The global commerce market is $25 trillion, and only about 20% online.

That’s $324 billion of opportunity vs. $20 trillion of opportunity. The last generation of internet companies were built on advertising, and the next generation will be built on commerce.

I’m going to examine this shift, and then look at three business models for commerce and the future of the internet:

➡️ The Shift from Advertising to Commerce

📅 Subscription

🎮 Microtransactions

💰 Virtual Currencies

➡️ The Shift from Advertising to Commerce

The first decades of the internet have been dominated by ad-based business models. When the internet was new, people weren’t yet comfortable transacting online; ads let the major internet sites remain free and accessible to anyone.

It’s also important to note the political and social climate around this time. The rise of the internet coincided with a post-9/11 erosion of privacy. After September 11th, Dr. Shoshana Zuboff argues, the U.S. government “[granted] new internet companies a license to steal human experience and render it as proprietary data.”

We’re now seeing the backlash to this invasiveness, with last week’s Big Tech hearings just the latest example. In addition to fast-changing public sentiment, the Google / Facebook duopoly (together the two capture 77 cents of every dollar spent on digital ads) makes an ad-based model less palatable to a new internet company.

The final nail in the coffin for advertising is what I alluded to earlier: creators can’t monetize effectively through advertising. Musicians provide an interesting analog here. Most musicians don’t make much money on Spotify—a musician makes $0.00437 per stream, meaning an artist needs ~3,500,000 streams just to earn the minimum wage of $15,000 per year. Unless you’re Drake or Beyoncé, it’s tough to make a living on streaming revenue.

As a result, musicians earn the lion’s share of their income through touring and live music. This is true for the big acts too: U2 makes 95% of its income through touring and Garth Brooks makes 89% of his income through touring.

Blake Robbins and Reed Duchscher pose an interesting question: what is the live music equivalent for creators? If YouTube is their Spotify (a broad place to reach lots of people and accumulate fans), how can creators better capture value from those fans in the way that musicians do with touring?

Maybe it’s merch, maybe it’s a Patreon, maybe it’s an OnlyFans. But it will come from some form of commerce. If YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram are the top of funnel for discovery, new tools and platforms will help creators better transact with their communities.

📅 Subscription

In 2000, The New York Times Company brought in $1.3 billion of ad revenue. Then ad revenue fell off a cliff. In its place, The Times invested in digital subscriptions. This graphic from Vox shows subscriptions replacing ads over time:

The chart only goes through 2016. Since then, the trend has accelerated: in 2020, ad revenue fell 26% while digital subscription revenue rose 30%.

The New York Times Company’s business model shift captures what’s happening across the internet: fewer ads, and more direct payments between creators (in this case, journalists) and consumers (in this case, readers). We see this in the rise of Substack, the continued success of Patreon, and the explosive growth of OnlyFans. The average American spends $237 per month on subscriptions, and many of the top paid apps like Tinder (dating), Strava (fitness), and Calm (mental health) rely on subscription.

In February, I interviewed OnlyFans creator and Fanhouse co-founder Jasmine Rice. Her words captured the shift from ads to subscription through a creator’s lens:

I’d only ever made money as a creator by tweeting sponsored content. A brand might pay me $25 to tweet something. I realized that I was renting out space on my feed—I was getting paid for my distribution, not for who I am.

I paywalled my OnlyFans page for $5 per month, which is the lowest price that OnlyFans lets you set. Subscribers get access to my whole feed of content.

I’ve made up to $35,000 in a month.

Discord, one of our investments at Index, is perhaps the first horizontal social platform to eschew ads. Instead, power users pay a subscription ($10/month or $100/year) to Nitro, which unlocks premium features like custom profiles, new emojis, and better video quality:

Discord started monetizing in January 2017 and has grown rapidly to $130 million in 2020 revenue (up 300% year-over-year). In the future, we’ll see more internet companies follow Discord’s model.

As time stays finite, content is exploding: the average person spends seven hours a day consuming digital media, up from three hours a day just a few years ago. Time is becoming more valuable. (In the rare cases when I watch TV instead of a streaming service, I’m struck by how frustrating it is to sit through commercials—the average is 16 minutes of ads per hour of TV. Consumer expectations are changing.) Because time is precious, people are willing to pay for quality. Subscriptions offer stable, recurring value exchange between creators and consumers.

🎮 Microtransactions

I know I’ve shared this chart before, but I’ll share it again—it’s becoming one of my favorites:

A decade ago, microtransactions made up 20% of gaming revenue; today, they make up 75%. By 2025, they’re expected to grow to 95%.

As is often the case, the broader consumer internet will follow in gaming’s example. Bite-sized purchases will become more and more common. Tipping is a form of this—paying a few bucks to your favorite creator. Ticketing is another example of a microtransaction, paying for one-time access (recurring event tickets would be another form of subscription revenue). In a blog post from January, Clubhouse signaled that it will forgo advertising in favor of tipping, ticketing, and subscriptions:

More and more internet companies are offering micro purchases: Cameo for shoutouts; Superpeer for 1:1 video calls; Jemi for personalized interactions; Looped for virtual events; Streamloots for gaming streamers. Even more traditional social networks are opting for this path: Yubo, a French social network with 40 million users, has monetized with in-app purchases and subscriptions from the start.

One of the most interesting examples is again OnlyFans, which lets creators “lock” direct messages. In addition to paying a subscription, fans also pay to access gated content in their inboxes. Here’s an example of what it looks like to receive a locked photo from a creator:

While messages seem intimate and personalized, creators can send a single message to every subscriber at the same time. If you have 100,000 subscribers and just 1% open your locked message, that’s 1,000 * $3.99 = $3,999 in income for a single message.

You can also see in the above screenshot that the platform incentivizes tipping by putting messages that include a tip at the top of the creators inbox.

💰 Virtual Currencies

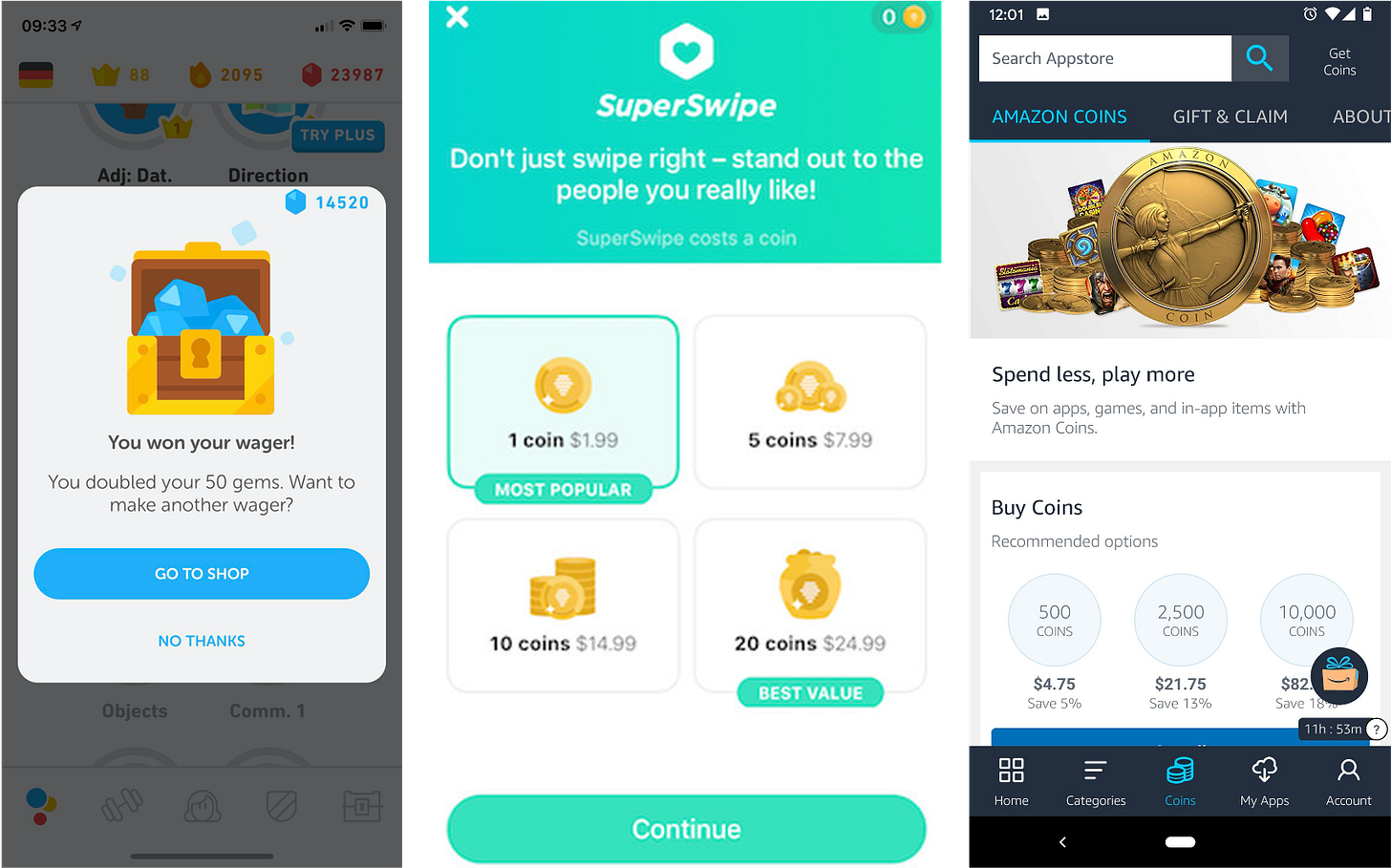

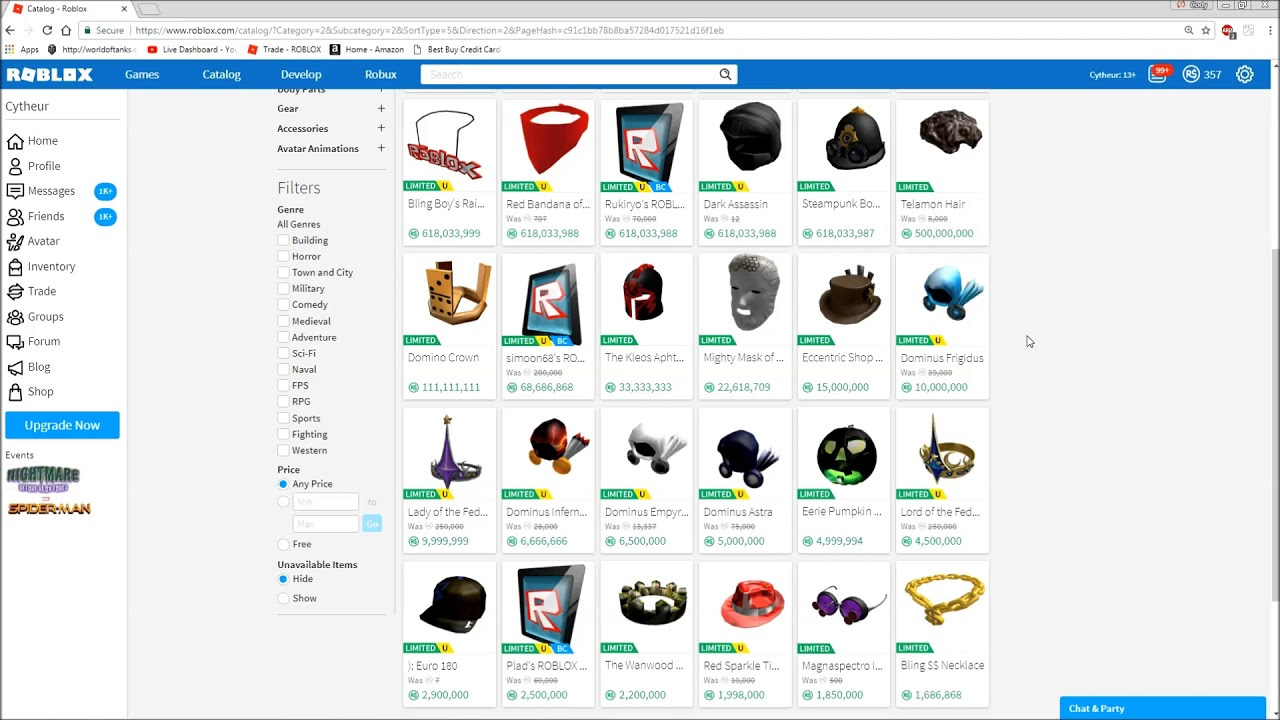

Virtual currencies go hand-in-hand with microtransactions. Roblox has Robux, Minecraft has Minecoins, and Fortnite has V-Bucks. Each is an in-game currency that lets you participate in a virtual economy. Here’s what it looks like to buy digital items like hats and necklaces using Robux:

Virtual currencies have evolved beyond gaming. On Duolingo, the language-learning app, you earn and spend an in-app currency called Gems. The dating app Bumble lets you buy packs of Bumble Coins—one SuperSwipe, a way to show someone you really like them, costs one coin. And Amazon has a little-known mini-economy using Amazon Coins, which let you spend on apps, games, and in-app items.

Virtual currencies can either let the user purchase directly with real dollars (e.g., 10 Bumble Coins for $14.99) or the user can earn the currency through an encouraged behavior. In this way, virtual currencies aren’t too different from airline frequent flyer miles or hotel loyalty points. The artist RAC is taking this one step further with $RAC, his Ethereum-based token. Fans can’t buy $RAC, but only earn by it buying merch, supporting RAC on Patreon, and so on. This provides a segue into another form of internet commerce: NFTs and social tokens.

🎨 Bonus: NFTs & Social Tokens

Fortnite is unique among in-game economies in that it brings in outside intellectual property. You can dress your avatar in your favorite NFL jersey thanks to a partnership with the NFL. You can purchase an Iron Man skin thanks to a partnership with Disney and the Marvel Cinematic Universe. But what if those items were more exclusive—what if there were only 100 Iron Man skins? And what if they were operable outside of Fortnite? You could wear your Iron Man skin over into Roblox.

This is where non-fungible tokens come in. As I wrote about in The Digital Renaissance, NFTs greatly expand virtual economies by enabling true digital ownership. NFTs are another building block for future internet business models.

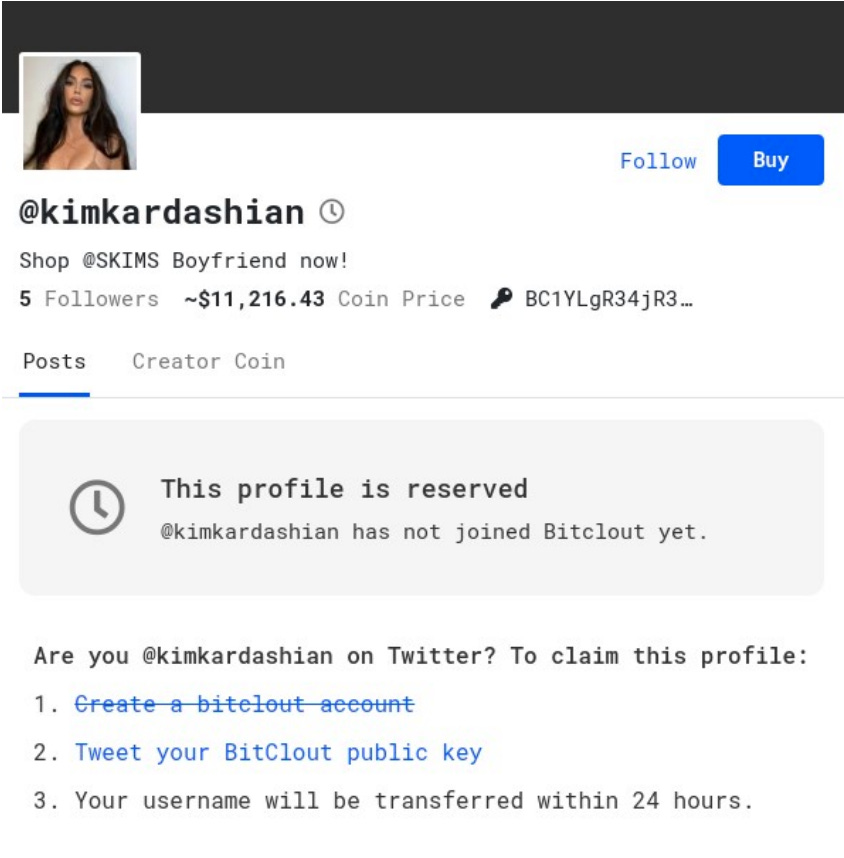

A related concept is social tokens, which differ from NFTs in that they’re fungible: every social token is interchangeable with every other social token. A creator can mint her own token and release a limited number. In recent weeks, BitClout has been getting a lot of attention for letting people buy and sell person-specific coins. There’s an Elon Musk coin, an Ariana Grande coin, a Justin Bieber coin. Here’s Kim Kardashian’s, which trades for $11,216.43:

I can’t help but think of the Black Mirror episode Nosedive, set in a world in which people rate each other based on every social interaction and in which everyone has a rating 1 through 5 (ratings 4.0 and up get special privileges).

But BitClout is also only formalizing the intangible currencies we already bestow on each other with social media follower counts, likes, job titles, and so on. This isn’t a new concept (status is central to human interaction) but rather just a new mechanism for better capturing status and value appreciation.

NFTs and social tokens are key components of the next generation of business models. They are the ultimate form of value capture and exchange—traceable and provable on the blockchain—and will lay the foundation for the internet’s next generation.

Final Thoughts

The internet is the driving force of culture: it’s how ideas spread, how content is consumed and shared, how people connect and communicate. Monetizing through ads leaves value on the table; to properly monetize culture, we need more complex, diversified, and innovative models that better capture and transfer value.

Ad-based social networks aren’t going away. YouTube, TikTok, Twitter, Instagram, and other platforms form the bedrock for content creation, distribution, and discovery on the internet. But they may become more commerce-centric over time.

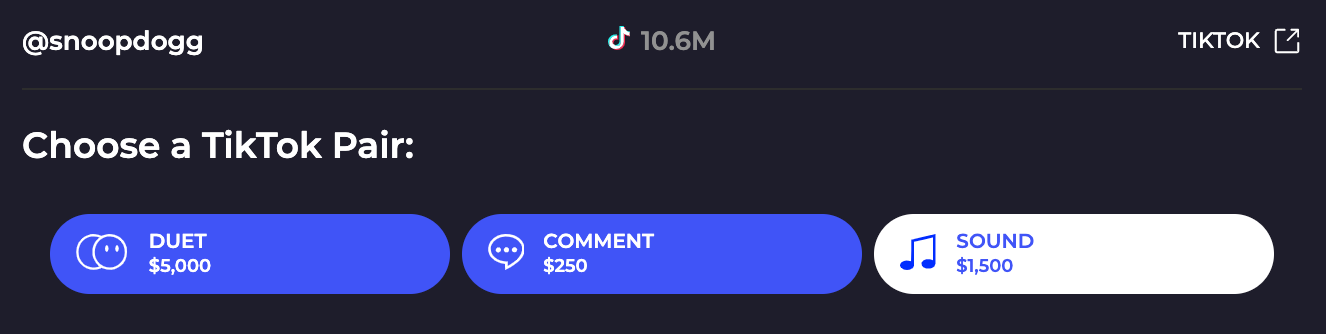

There’s already an ecosystem of commerce-based companies sitting on top of the ad-based horizontal social platforms. PearPop, for instance, is built on TikTok and lets fans pay for creator interactions: Duets, comments, Sounds. Snoop Dogg will Duet you for $5,000, comment on your post for $250, or use your sound for $1,500.

It’s easy to see TikTok adding a feature like this directly. Or imagine Instagram letting you paywall the “Close Friends” feature, or letting you pay to get your DM to your favorite creator highlighted at the top of her inbox. Twitter is already layering on commerce features with features like Super Follows, which let you pay a few bucks for exclusive content and more access to a creator.

The big ad-based platforms will become more commerce-focused over time, and emergent platforms will likely start with subscription, microtransactions, or virtual currencies—or stitch together all three. In this future, platforms will capture more of the value that they create, creators will more easily earn a living, and consumers will have a better experience online.

Sources & Additional Reading

This Is How Much YouTube Paid Me For My 1,000,000 Views | Shelby Church

YouTube and Patreon Still Aren’t Paying the Rent for Most Creatives | Herbert Lui, Marker

Creator Economics | Blake Robbins and Reed Duchscher

The Preteen’s Guide to Getting Rich Off YouTube | Lucas Shaw and Mark Bergen, Bloomberg Businessweek

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox each week: