How Twitter and the Internet Broke the News

This is a weekly newsletter about tech, media, and culture. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Today’s piece is the fourth (and final) in a series on consumer social platforms.

If you missed them, here are the pieces on TikTok, Instagram, and Snap:

🎵 Why TikTok Is So Groundbreaking

🛍️ Instagram’s Mid-Life Crisis

👻 Snap, Niantic, And Our Augmented Reality Future

Twitter & The Unbundling of News

Mark Zuckerberg doesn’t mince words when it comes to Twitter. Zuckerberg once told friends: “Twitter is such a mess, it’s as if they drove a clown car into a gold mine and fell in.”

That’s a little harsh, but it’s also not too far off. Twitter’s cultural and societal impact is massive—what other platform does the President use 200 times a day? But Twitter consistently fails to capitalize on that impact.

Compare revenue across major consumer social platforms:

Twitter’s revenue isn’t commensurate with its value creation. (You can’t convince me that LinkedIn creates more cultural and societal value than Twitter.) The story is even worse on a per-user basis. Twitter’s ARPU (Average Revenue Per User) for North America is about $20; Facebook’s is over twice that. And while Facebook’s stock is up +570% since its IPO, Twitter’s stock is trading below where it traded on its IPO day.

This is a piece about Twitter, but it’s also a piece about how the Internet changed how we consume and share information online. An alternate title could be “How the Internet Disrupted News”. Twitter was both a catalyst of and beneficiary of that shift. But while it creates enormous value, it keeps little of it.

To understand this, I’m going to look at:

How the Internet changed news and Twitter’s role in it.

Why Twitter’s business model needs to change.

The Unbundling of News

There’s some debate about whether Twitter is a social network. Twitter does have a social graph—you follow people, and they follow you back—but it primarily functions as a content sharing platform. I would argue that Twitter began as a social network in the vein of Facebook and Instagram, but evolved into a content platform more like YouTube and TikTok.

Two events, both in 2009, marked this shift:

First, on January 15, 2009, US Airways Flight 1549 made an emergency landing on the Hudson River. The first report of the incident didn’t come from a traditional news outlet, but from Twitter:

The “Miracle on the Hudson” revealed Twitter’s true value and purpose. The Internet (and mobile Internet, in particular) was rapidly changing how information could be shared. What used to take a CNN crew could now be done by anyone with a smartphone.

Later in 2009, Twitter switched from asking “What are you doing?” to “What’s happening?” The change in wording was subtle, but important: it positioned Twitter as a site for reporting all of the world’s news, rather than as a site for reporting what you had for lunch.

Twitter continued to disrupt the old guard. During the Arab Spring, violent protests broke out in Iran. While news of the protests spread around the world on Twitter, CNN was reporting the “news” that semi-nude photos of Miss California had surfaced online. The hashtag #CNNFail began to trend.

Suddenly, Twitter was the place to share the world’s information. Twitter’s retweet feature made it uniquely suited to viral content; content could reach well beyond a user’s social graph. Facebook and Instagram, in contrast, weren’t wired for virality.

Ashton Kutcher, appearing on The Oprah Winfrey Show, summed up Twitter’s rise:

“This is a commentary on the state of media. I believe we're at a place now with social media where one person's voice can be as powerful as a media network. That is the power of the social web.”

In order to understand the world that Twitter grew up in, it’s important to digress for a minute to look at how the Internet was changing media.

The Internet gave everyone a voice. It’s hard to get your op-ed in The New York Times, but anyone can write online. One out of every three websites in the world is a blog (some 500 million sites) and 2 million blogs are published every day.

With people getting their news online, the newspaper industry began to crater:

In its place, a new generation of digital media startups emerged. These startups basically resembled online newspapers: they covered a variety of topics and they still made money through ads. Their ad-based models created a race for “clicks”, with writers using clickbaity headlines to drive eyeballs and, thus, ad revenue. This had the effect of emphasizing quantity over quality.

Most digital media companies from this era struggled—they simply didn’t have the scale to survive on ads. In the words of one editor-in-chief: “Even very well-read stories for large outlets may only generate $75 or $100 in revenue online. Not enough to pay a writer for a day’s work.”

The second generation of digital media startups began to finally unbundle the newspaper and move away from ads:

By verticalizing, digital media companies could tap into more valuable niche audiences. Many of the companies above eschewed ads in favor of subscription or events, which better mined value from their most engaged customers.

So where does Twitter fit into all of this? The Internet created an explosion of content; Twitter helps make sense of it. Twitter is online media’s tool for discovery—for finding and acquiring customers.

In a cover piece for Time magazine, Steven Johnson wrote:

“Partially thanks to the move from asking people to talk about their status to talk about what's happening, Twitter has become a pointing device instead of a communications channel: sharing links to longer articles, discussions, posts, videos — anything that lives behind a URL. It's just as easy to spread the word about a brilliant 10,000-word New Yorker article as it is to spread the word about your Lucky Charms cereal habit.”

As the Internet reinvented media, Twitter became the map by which to chart the new media landscape. But as Twitter grew critical to the value chain of information on the Internet, it failed to capture its opportunity.

Just taking a quick breather to remind you to subscribe if you haven’t already!

A Long-Overdue Business Model Shift

Let’s cut straight to the chase: advertising isn’t the right business model for Twitter. Twitter doesn’t have the scale for advertising (it has about 10% as many MAUs as Facebook) nor the ad chops (hence its low ARPU).

But Twitter is unique among social apps in that it has a small portion of users who are very, very engaged. According to Pew Research, the top 10% of Twitter users account for 80% of all tweets:

44% of all Twitter users have never tweeted; of 550 million users that have, half sent their last tweet more than a year ago.

This skew signals that Twitter can more deeply monetize its power users. It can borrow lessons from other companies on how to do it:

LinkedIn & Discord

Consumer social platforms can be roughly mapped across those primarily for entertainment, and those primarily for utility:

Twitter operates like it’s built for entertainment, but it’s built for utility. This puts it in the company of LinkedIn and Discord.

LinkedIn doesn’t make much money from ads. Most of its revenue comes from subscriptions sold to professional recruiters and from premium plans for power users:

In arguing that Twitter should follow LinkedIn’s model, Packy McCormick put it concisely: “On professional networks, like LinkedIn, most users are the product, but power users are the customers.”

Discord is another example. As a chat platform used mostly for gaming, Discord seems at first glance to be built for entertainment. But Discord is mission-critical for gamers, making it a utility product. Discord has a freemium business model and doesn’t serve ads at all. For $9.99 / month or $99 / year, Discord Nitro users get a variety of premium features beyond the free tier’s features.

To Twitter’s credit, it is (finally) exploring a subscription option. TechCrunch reported a survey of potential features that Twitter sent out and The Verge reported that Twitter listed a job opening for someone to work on subscription.

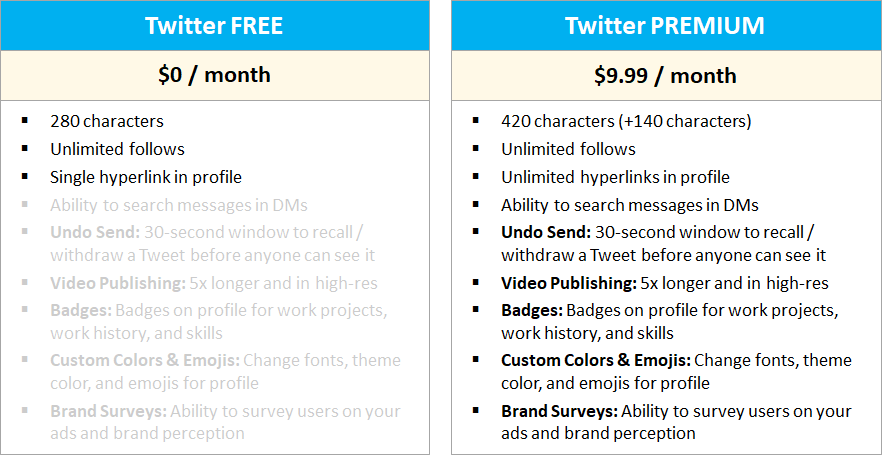

Here’s my mock-up of what a pricing plan could look like:

Substack & The Athletic

Substack and The Athletic deliver value to customers while also building sustainable, scalable businesses.

Substack (which is where I write this newsletter) grew 60% in the first three months of the pandemic. The New York Times columnist David Brooks wrote of Substack:

The next good thing is there are no ads, just subscription revenue. Online writers don’t have to chase clicks by writing about whatever Trump tweeted 15 seconds ago. They can build deep relationships with the few rather than trying to affirm or titillate the many.

At TPG, we invested in The Athletic, which is a subscription offering for local sports coverage. The Athletic realized that local sports fans are die-hards and that they’ll pay money for best-in-class sports journalism. The company just hit 1 million subscribers, $60 million in revenue, and a $500 million valuation.

Both Substack and The Athletic do what the Internet does best—carve out deep, lucrative niches—and both rely on Twitter for discovery.

I recently got this email in my inbox from Substack:

Substack and The Athletic are creating enormous value for the media ecosystem—off of Twitter’s back—and they’re reaping all of the rewards. Twitter reaps nothing.

Twitter needs to earn a share of revenue from the traffic it drives, across the Internet. It can also easily launch a Substack competitor (paywalled long-form writing) and offer media outlets paid placement on dedicated pages for various niches.

In July, Twitter reported second-quarter ad revenues of $562 million, a 23% decrease year-over-year. Twitter’s influence is surely greater than it was a year ago; shouldn’t its revenue reflect that?

A shift away from advertising is happening across the Internet: I’ve written about how Fortnite has a $100 ARPU (over twice Facebook’s) by monetizing with microtransactions and about how Influencers can now earn money in ways beyond ads. What’s elegant about business models like Discord’s, Substack’s, and The Athletic’s is that they better align willingness to pay with ability to pay. They allow less value to leak out of the system.

Final Thought: Digital Darwinism

When I think of Twitter, I think of Digital Darwinism. Digital Darwinism is the phenomenon that technology and society evolve faster than an organization can adapt.

This may just be a nicer way of phrasing Zuckerberg’s clown car comment. Twitter happened upon a once-in-a-generation shift: the Internet was changing everything about the flow of information. Twitter stumbled into such a massive opportunity that it couldn’t evolve quickly enough to ride the wave.

But if Twitter can understand its place in the media ecosystem—as a wayfinder of sorts for a sea of Internet content—and if it can pivot to a business model that better serves its most valuable users, it can better align cultural value and financial value. It can begin to capitalize on its potential.

Sources & Additional Reading

Check these out for further reading on this subject:

Hatching Twitter by Nick Bilton. I can’t recommend this book enough. It reads like a novel and is full of incredible reporting.

If you’re interested in how the Internet has changed the newspaper industry, Benedict Evans has a good piece on it here.

Scott Galloway argues for a Twitter subscription model—and for lots of media acquisitions—here.

Packy McCormick has a good take on Twitter here, including the Bill Gates Line and the “Jobs To Be Done” framework. I especially like Packy’s point that Twitter messing up Vine may have been a blessing in disguise.

David Brooks’ piece on the evolving media landscape: The Future of Nonconformity.

Ben Thompson has some great writing on the changing news environment; my favorite is Never-Ending Niches.

For a deep-dive on how The Athletic got to 1 million subscribers, check out this piece.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox weekly: