I'm a Business, Man

The Disaggregation of Work

This is a weekly newsletter about how people and technology intersect. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

I'm a Business, Man

Jay-Z was born in Brooklyn and grew up in a housing project, raised by a single mom. In high school (where he was classmates with both The Notorious B.I.G. and Busta Rhymes), Jay-Z sold crack cocaine to get by. His life began to change when his mom bought him a boombox for his birthday, sparking an interest in music that led to a debut rap single in 1995.

Ten years later, Jay-Z famously rapped, “I’m not a businessman, I’m a business, man.”

And he was right. In 2019, Jay-Z became hip-hop’s first billionaire; today, he and his wife, Beyoncé, are together worth $1.9 billion. Jay-Z’s net worth has swelled 40% this year, following the sale of his Armand de Brignac champagne brand to LVMH and the sale of his Tidal music streaming service to Square. His net worth is also diversified; this is how Forbes estimates it:

$425 million in cash and investments (largely from the Tidal sale)

$320 million remaining stake in Armand de Brignac

$140 million in Roc Nation

$120 million in D’Ussé

$95 million in music catalog

$70 million in art collection

$50 million in real estate

A quarter-century after that debut single, and 15 years after first rapping those words, it’s official: Jay-Z is his own business, man.

I often think of Jay-Z’s lyric when I think of one of today’s most massive and consequential economic shifts: the disaggregation of work.

People are becoming their own businesses. If mom-and-pop shops were the small businesses of 20th-century America, individuals are the small businesses of 21st-century America. Freelancers, contractors, creators—they’re all examples of economic individualism. And the infrastructure built to support “traditional” work will need to be refreshed or rebuilt to serve disaggregated work.

I’m going to first look at the state of freelancing today, and then at the infrastructure layer being built to undergird the new work economy.

State of the (Freelancing) Union

Today, nearly 70 million Americans earn income as freelancers; by 2028, that will swell to 90 million. In 2026, America will become a majority-freelance economy.

There are various drivers of this shift, including tax incentives and the fact that reclassifying workers as 1099 employees typically saves a company money. But the biggest driver—and the most important—is a generational mindset shift around work. Younger people want three things from work: (1) autonomy, (2) flexibility, and (3) financial upside. Independent work gives them all three.

The desire for autonomy and flexibility shows up beyond freelancing. A May 2021 survey of 1,000 U.S. adults showed that 39% would consider quitting if their employers weren’t flexible about remote work. Among Millennials and Gen Zs, that figure was 49%. In one young woman’s words: “They feel like we’re not working if they can’t see us. It’s a Boomer power-play.” To younger Americans, commutes and office cubicles are nonsensical remnants of the past.

Last week, I wrote about the viral TikTok video in which a man rants against traditional work:

“98% of the United States population that has been brainwashed into believing that it’s normal to give up 5 out of every 7 days of your week just to make someone else rich for 40, 50 years doing something you don’t even actually enjoy just to get 10 years of freedom before you’re too old to actually enjoy it.”

His words capture his generation’s sentiment towards work. Independent work means choosing when you work, where you work, and what you work on.

Contra, a professional network for independent workers, put out an excellent report this week on the rise of freelancing. The report showcases workers like Jill Russell, a freelance designer. Jill reflects on her newfound flexibility and autonomy:

The report also emphasizes how revenue streams are diversifying. Workers traditionally relied on a single source of income. Most freelancers have various projects going at once, or stitch together “side hustles” to earn a living.

While charging by the hour is more common today, there’s a shift toward project-based pricing, which gives workers even more flexibility and autonomy.

Last year, a study by Upwork found that 75% of freelancers report earning the same or more than they’d earned as traditional employees. While the source isn’t impartial (Upwork is certainly incentivized to encourage freelancing), various studies have reached a similar conclusion. Freelancing leads to more variability in income, but also often entails higher financial upside than a flat salary.

Independent work aligns with the way that younger workers approach work—as entrepreneurs and investors. They’re tired of renting their time to corporations: they watched their parents and grandparents do that, only to be burned in the 2008 recession and again in the 2020 pandemic. Corporations aren’t reliable; corporations don’t have your interests at heart. Younger workers would rather dictate their own fortunes through hustle and grit. They want to own equity that appreciates, and they understand that equity is the path to true wealth creation.

Bryce Hall and Josh Richards are two of TikTok’s most popular creators—between them, the 21-year-old and 19-year-old have 45 million followers and 3 billion likes. Red Bull’s interest was piqued by that influence, and the brand asked Hall and Richards to be brand ambassadors. The two thought about it, but decided to instead launch their own energy drink. The result was Ani Energy.

In a similar vein, the Gen Z-focused fintech company Step counts Charli D’Amelio, TikTok’s most-popular creator, among its investors. Ten years ago—even five years ago—D’Amelio would just get paid to promote the brand. Now she’s on the cap table.

Bryce Hall, Josh Richards, and Charli D’Amelio capture the Gen Z mentality shift: instead of renting your skills to enrich someone else, own your own equity upside. Be an entrepreneur. Be an investor. Millennials and Gen Zs have business savvy, and independent work taps into that shrewdness.

The Infrastructure of Work

Around 156 million Americans—about 50% of the population—get their healthcare from their employer. For 80 years, employers have provided much of the American social safety net. As work disaggregates, that safety net evaporates. A new infrastructure needs to be built for a new work economy.

We’ve seen this over the past decade with the rise of the gig economy: Uber, Instacart, DoorDash, Fiverr, Upwork. The Contra report frames this era as encompassing platforms that focus on roles and tasks.

These are standardized skills: driving, food delivery, grocery delivery. And millions of Americans today earn a living on these platforms: Uber, as one example, employs 1 million drivers in the U.S.

But we’ve also seen the gig economy fall short in supporting its workers. Uber drivers, Instacart shoppers, DoorDash dashers—all lack benefits like healthcare, life insurance, disability insurance, and pensions. My partner Sarah Cannon offers a solution: allocate benefits proportionally to a workers’ time. A worker who spends 15% of her time working for Instacart and 25% working for Lyft could have 15% of her benefits covered by the former and 25% by the latter. But despite regulatory and social pressures, the gig economy hasn’t evolved to provide the safety net of traditional work.

A decade after the gig economy was born, we’re seeing the (continued) rise of the creator economy, focused on individualized and specialized skills: writing on Substack, teaching on Outschool, making videos on TikTok.

This movement is just getting started, catalyzed by vertical platforms that create more scalable and economical forms of work. You can be a gaming coach on Metafy, a fitness instructor on Interval, a website builder on Webflow.

All of these internet platforms have expanded the meaning of work. And as work splinters, as people become businesses, the new infrastructure of work remains nascent. Three key opportunities for innovative solutions are (1) financial services, (2) benefits, and (3) mental health.

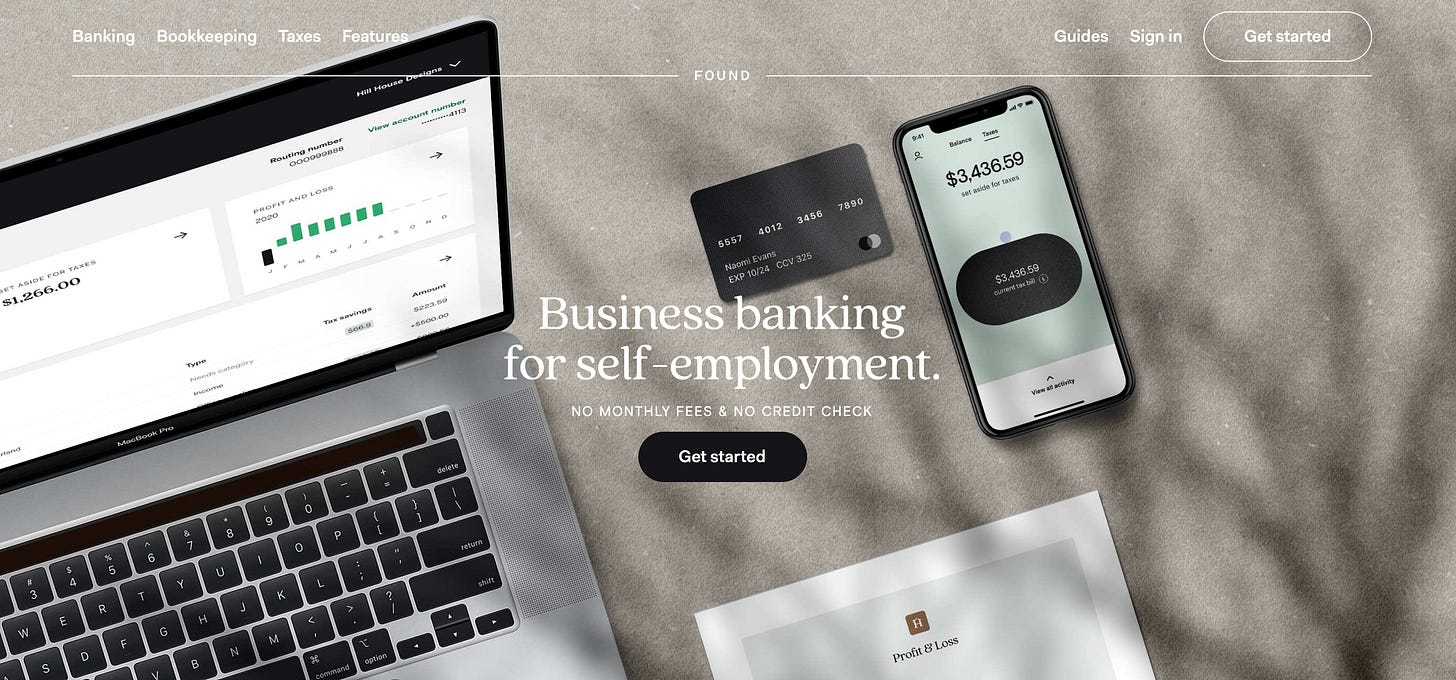

Within financial services, the entire suite of fintech tools built for corporations and small businesses needs to be replicated for freelancers. An example is Found, which is building business banking for the self-employed.

Benefits, as mentioned earlier, have traditionally come from employers; gig and creator platforms have yet to offer their workers benefits. In their absence, companies like Catch are emerging to offer benefits—including tax withholding, time off, retirement, health insurance—to freelancers.

And mental health is uniquely challenging. Taylor Lorenz wrote a recent piece for The New York Times on creator burnout. One creator said, “I get to the point where I’m like, ‘I have to make a video today,’ and I spend the entire day dreading the process.” Another said, “When creators do try to speak out on being bullied or burned out or not being treated as human, the comments all say, ‘You’re an influencer, get over it.’” One YouTuber perhaps put it best: “If you slow down, you might disappear.”

Creators get punished for taking breaks. I took a year off Instagram in 2019 and lost 50,000 followers. I still had income from my primary job, but many don’t: for them, lost followers means lost livelihood.

Independent workers don’t get paid-time-off or sick days. There’s no opportunity to focus on your mental health by taking a break. There are ways to fix this: platforms could offer workers paid vacation days and sick days, or could offer maternity and paternity leave. Or, for a fee, third-party platforms could pick up the slack.

Across financial services, benefits, and mental health—as well as across various other categories—there are opportunities to build the bedrock of the new work economy.

Final Thoughts

If freelancing appeals to workers for its autonomy, flexibility, and financial upside, freelancing’s growth is fueled by technological, macroeconomic, and cultural forces.

On the technology front, internet platforms have enabled new forms of work. They connect worker and consumer, often making work more global, scalable, and frictionless. They make it feasible to earn a living wage online.

On the macro front, the COVID pandemic accelerated the disaggregation of work. Many people found themselves out of work or more distrustful of traditional work. They turned to tech-enabled jobs or decided to dictate their own fate by going solo.

And, most meaningfully, on the cultural front, the disaggregation of work embodies the ethos of a new generation. It’s a reaction to institutional, centralized power, and a reaction to unprecedented inequality.

The Gini Coefficient measures income inequality, with a higher number equating to more inequality. America’s Gini Coefficient has trended steadily upwards over the last 50 years.

That chart helps explain why work is changing. The forces that led to Occupy Wall Street in 2011 are the same forces that led to GameStop mania in January. As one r/WallStreetBets redditor wrote during the GameStop craze, “This is the first time we all literally get to decide our destiny.”

The disaggregation of work is about that control—that ability to control your destiny. You reclaim your agency from “the system” and you control your own career arc. You aren’t a businessman, donning your suit and tie and commuting on the Metro North and dreaming of the day you get to stick it to the man. Those days are over. You’re a business, man.

Sources & Additional Reading

Check out the Contra Freelance Industry Report for a holistic and interesting overview of how workers are turning to independent work

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox each week: