This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Influencer Marketing 2.0 🤳

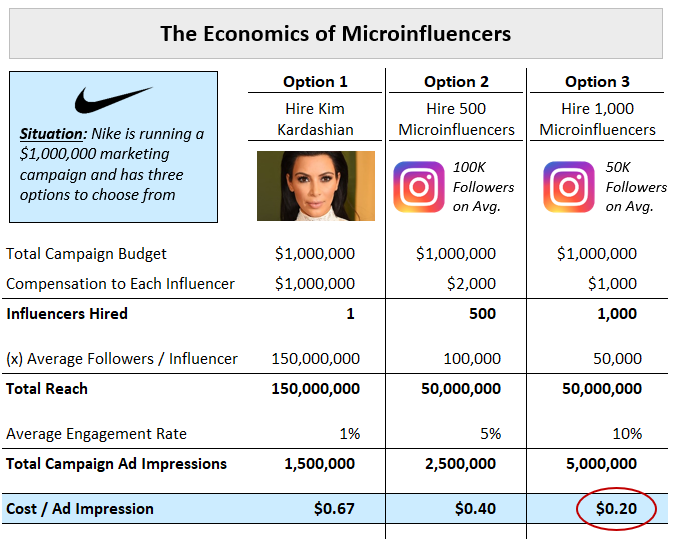

Two years ago, I created this chart for a piece called The Evolution of the Influencer:

I wrote at the time:

A general truth on internet platforms is that smaller audience sizes have higher engagement rates. In other words, someone with 1,000,000 followers might average 1% engagement (likes + comments) on their posts. Someone with 100,000 followers, meanwhile, might average 5% engagement.

This means that “microinfluencers”—people with ~10K to ~100K followers—have better economics for brands. In the example here, Nike could spend its entire $1,000,000 budget to hire Kim Kardashian, who has a ~1% engagement rate on her posts. Or it could hire 1,000 microinfluencers, each with 50K followers, and receive more impressions per dollar spent.

Aside from the slight oversight that Nike would probably never work with Kim K (not sure why I picked that combination!), the example holds up. Of course, the numbers aren’t accurate—engagement rates aren’t typically that high—but they prove the point: brands can benefit by tapping into the long tail of social media users, who have more engaged followings and are seen as more authentic and relatable.

In the two years since writing that post, a lot has changed. For one, Kim K now has 311M followers vs. 150M. (Though her younger sister Kylie surpassed her to take the family crown 👑 , with 338M.) But most crucially, we’ve seen tectonic shifts in the advertising world: customer acquisition costs for brands are getting prohibitively expensive, forcing brands to consider alternatives to the Google-Facebook duopoly. Last summer, Google and YouTube CPMs (cost per mille—the amount an advertiser pays for 1,000 impressions) were up 108% year-over-year. Facebook ad costs were up 89%. TikTok CPMs were up 92%, and Snapchat CPMs were up 64%. Granted, these numbers are relative to 2020’s slightly-depressed, COVID-impacted levels. But the trendline holds: it’s getting more and more expensive to acquire customers through traditional online channels.

As a result, brands are hungry for new acquisition channels. More and more brands are turning to influencer marketing, which has grown from a $5B industry in 2018 to a $14B industry in 2021, up 40% year-over-year.

Influencer marketing gets a bad rap: for many people, it evokes reactions similar to the reactions one might have reading Kim K’s book of Instagram selfies. It’s seen as cringeworthy, vapid, mercenary, self-aggrandizing, inauthentic. But derision shouldn’t mean dismissal. Influencer marketing should be taken seriously. (For what it’s worth, Kim sold 125,000 copies of that book.)

Influencers are a key part of any brand’s marketing playbook. A single Instagram post from someone like Kylie Jenner can get close to 100M impressions (though it will cost a brand $1M+). That reach might be equalled only by a Super Bowl commercial.

Nearly every celebrity in the world does sponsored social media posts—they’re the 21st-century version of magazine adverts, but with the internet’s zero marginal costs on their side.

Much of the growth in influencer marketing—and much of the remaining opportunity—comes not from the bold-faced names, but from the content creators with 10K, 1K, or even 500 followers. The lines between content and commerce are continuing to blur.

(One side note: I typically prefer the word “creator” to “influencer.” I like how Patreon’s Jack Conte frames the difference: “influencer” extracts the one thing advertisers care about—influence—and overlooks creativity and self-expression. As he puts it: “I don’t wake up in the morning to influence; I wake up in the morning to create.” That said, when discussing advertising directly, I often use influencer and creator interchangeably.)

While influencer marketing has exploded as an industry, little has changed about how it works. It’s clunky and opaque. A typical campaign might look something like this:

Say I’m the social media manager at Warby Parker, and I want to launch influencer marketing. I turn to a product like Grin, CreatorIQ, or #Paid to search for and select influencers who might be good brand ambassadors. Maybe I filter for women between the ages of 18 and 35, who live in major cities and who wear glasses 🤓

Next, I agree to a flat fee for an agreed-upon deliverable—for example, paying an influencer $3,000 for one Instagram post and three Instagram stories.

The influencer creates her content, sends it to me for approval, and posts it. She gets paid, typically regardless of how the content performs. She might add a discount code (“Use RACHEL15 for 15% off!”), mostly as a hack so that I can track attribution.

This process has several fault lines. The past few years have seen some progress to fix some of them (including great products like Grin), but both brands and creators are left wanting. There are interesting areas ripe for innovation. Three of them:

1️⃣ Scalable User-Generated Content

2️⃣ Influencer Commerce Tools

3️⃣ Affiliate Commerce

Let’s take each in turn.

1️⃣ Scalable User-Generated Content

Here are three problems with the above example of an influencer campaign:

Influencers often aren’t actual customers of a brand.

It’s difficult to scale the strategy beyond a small number of influencers.

Most of the ROI from influencer marketing comes from owning the content, and then putting ad dollars behind it. Many campaigns don’t touch usage rights.

Some new companies are solving all three problems.

Bounty, for instance, lets customers earn income by posting on social media about what they buy. Bounty lives in the checkout flow of a brand, either in your cart or on the Thank You page. Here's how Bounty looks on the Thank You page when I buy from Jones Road Beauty (and yes, my full name is Rexford):

The call to action is “Get paid when you post on TikTok!” and when I sign up, Bounty helps me track my order shipment and reminds me to post when my product arrives. If my video gets a million views—and with TikTok’s potential for virality, it just might—I may make a thousand bucks. Not bad.

Brands win because they get actual customers to post content—the quality and authenticity of user-generated content is likely higher than more polished, sponsor-y content from professional influencers. Sure, some of it might be garbage, but some of it might be gold. And brands are paying on a CPM basis—in other words, they only pay for content that performs well.

Most importantly, brands can buy usage rights to that content, and then run their own ads with that content. On TikTok, these are called spark ads—a native ad format that lets a brand put dollars behind a creator’s organic content. In this way, Bounty can become the dashboard through which brands manage and control user-generated content.

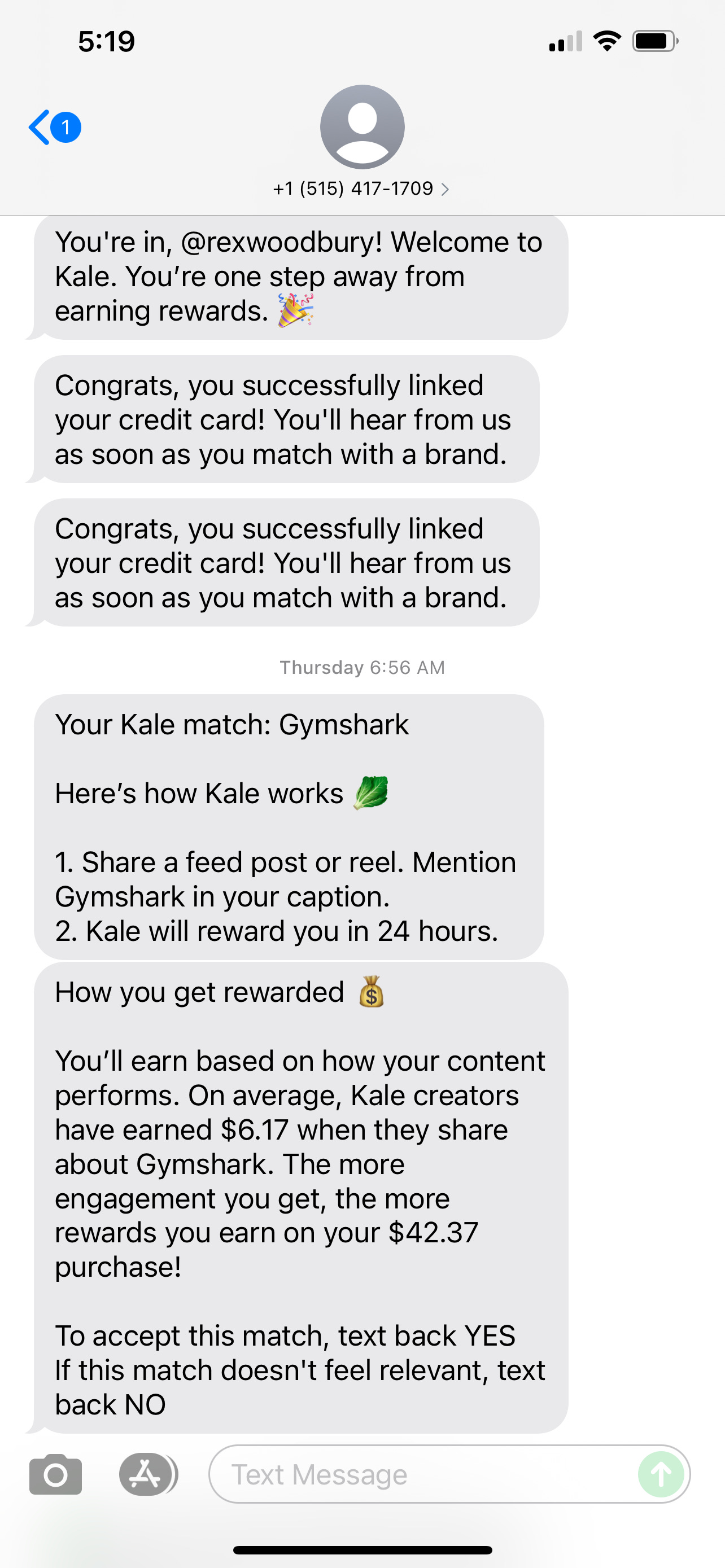

Kale is going after a similar opportunity to Bounty, but with a slightly different approach. On Kale’s website, I can sign up as a creator. Anyone can, no matter how many followers you have. Kale uses Plaid to link to your bank account and credit cards. Then Kale texts you about brands you buy from, encouraging you to post on social and earn $$.

Here’s a text I received from Kale encouraging me to post about the Gymshark tank top I bought:

Bounty and Kale (and other players in this space like Swaypay) are interesting in how they flip the order of operations: brands aren’t paying hefty sums upfront, and then seeing little ROI. Rather, brand incentives are aligned with creator incentives. Plus, they crowd in more people as creators. As for the three problems outlined above: 1) real customers are now influencers for a brand; 2) the marketing channel is scalable and easy to manage; and 3) brands can buy well-performing content to power ads, creating a new content creation channel and giving creators/customers a new income stream.

2️⃣ Influencer Commerce Tools

The 800-pound gorilla in the influencer space is LTK, the renamed company that resulted from the marriage of LikeToKnowIt and rewardStyle. LTK was founded by Amber Venz Box, an influencer in her own right who created a way for influencers to get paid for product recommendations.

LTK initially became known for “shoppable screenshots.” I actually used to be an LTK influencer circa 2017. If you took a screenshot of my Instagram post, you could go to the LTK app (then LikeToKnowIt) and shop each item I was wearing in the post.

Today, the LTK app is a major destination for shoppers. Here’s how my app looks:

I can see influencers I follow, and then below each image an influencer posts, I can see the products that influencer is wearing. I can click on any of them to purchase.

LTK works with about 5,000 retailers and a million brands, connecting them with influencers to showcase their products. Those influencers earn affiliate revenue by tagging their content with links that followers click on to buy. LTK was valued at $2B last fall and does about $3B in GMV for brands on its platform.

Another tool in the influencer playbook is comment selling. Comment selling is a huge and under-talked-about business, and CommentSold is a huge and under-talked-about company.

Comment selling is what it sounds like: an influencer will share a product recommendation through videos or photos (often through livestreaming) and instruct shoppers to purchase by commenting “sold.”

Comment selling is sort of a modern-day version of QVC—immersive, real-time, social shopping.

CommentSold offers influencers tools to do comment selling: invoice management, conversational replies to shoppers, inventory management, and so on. Most influencers are selling on Facebook Live or on their custom storefront. CommentSold was founded only in 2017, and is doing over $1B in GMV.

LTK and CommentSold are two examples of companies giving influencers new platforms and tools through which to earn income—this is an interesting space to watch as content and commerce continue to meld.

3️⃣ Affiliate Commerce

Affiliate commerce is big—about 16% of global e-commerce sales big. Affiliate marketing is when someone promotes a product through a link, and receives a cut of sales in return. Amazon has an affiliate program called…well, Amazon Affiliate Program—chances are that if you’re reading a blog and it links to a book on Amazon, that writer is making a cut of book sales. Affiliate marketing can quickly become big money. Say you run a blog about electronics. You get 10,000 readers a day. Of those 10,000, 500 (5%) click a link in your piece to an Amazon page for a $1,000 smart TV. Amazon Affiliate Program pays 2% commission on TVs. Say that of those 500 visitors, 50 buy the TV. That’s 50 * $1,000 * 2% = $1,000. Not bad for one day’s visitors to a blog post that might live evergreen in Google search results.

Yet when it comes to influencers, affiliate links are surprisingly clunky and opaque.

LTK is probably the most robust business for influencer affiliate links, with LTK’s 150K influencers earning income every time someone shops a product they promote. Of the $3B LTK generates for brands each year, 10-25% goes to influencers. But LTK creators are 90%+ white women focused on fashion and beauty. There are millions of creators who inspire commerce transactions, but don’t see any revenue from it.

Affiliate commerce should become more important as the influence of the individual grows. I’ve shared this chart many times, depicting our society’s shift from institutions to corporations to people:

I’m moving to New York next week, and I’m in the market for new furniture. If I’m shopping for a new couch, why would I want Crate & Barrel to take all the revenue when some of it could go to the amazing interior design creator I’ve admired for years on Instagram? I’d rather my hard-earned dollars go to someone I “know” and have a relationship with, rather than to a faceless corporation.

There are some interesting companies emerging. Shop My Shelf lets you effectively shop the shelves of creators. Here’s what it looks like on the page of Ashunta Sheriff-Kendricks, a top celebrity makeup artist:

But I still can’t tell in the checkout flow how much is going to Ashunta. Showing this would increase conversion. It should say, “15% of your purchase will support Ashunta.” People buy Chamberlain Coffee because they like coffee, but also because they like Emma Chamberlain.

People like buying from people they know and trust. And on the internet, we know and trust people we’ve never met, but who we share digital intimacy with every day. Commerce needs to catch up.

If you’re an influencer who has sold through affiliate links, or an agent who works with influencers, I’m curious to hear your view on what works well and what’s broken. Shoot me an email.

Final Thoughts

It feels like after years of stagnation, there’s a lot happening in the intersection of creator and commerce. Maybe brands are feeling the pressure of rising CACs, and demand for new channels is up. And as we all spend more time online, we all create more content and thus inadvertently become brand evangelists. Why shouldn’t we get paid for that? The pie of advertising dollars—today hoovered up mostly by Google and Facebook—will be more evenly distributed, with better scalability, better attribution, and better discovery-driven commerce.

Sources & Additional Reading

You can read more about comment selling here

Here are two interesting interviews (I, II) with Amber Venz Box about LTK

Check out the companies mentioned here: Grin, CreatorIQ, #Paid, Bounty, Kale, Swaypay, LTK, Commentsold, Shop My Shelf

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: