Innovation In Media: Reinventing How Ideas and Culture Spread

Examining Innovation Across Film & TV, Books, Music, Gaming, & UGC

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Innovation In Media: Reinventing How Ideas and Culture Spread

Over the past decade, “media” has become something of a bad word in the startup and venture worlds. To many, media came to signify ad-based, clickbaity websites that pumped out content. In the mid-2010s, for instance, venture-backed companies like Vice and BuzzFeed were churning out hundreds of pieces of content per day.

But media is more than digital publishing. The definition is broader: media is the means of communication that reach or influence people widely.

Some of the largest and most influential businesses in the world are media businesses: Disney and Netflix, The New York Times Company and Viacom, Nintendo and Activision Blizzard. I’d argue you can add Meta, Tencent, and Bytedance to that list.

I’ve always been fascinated by media—by how content flows between people, transferring ideas, emotions, and worldviews in tandem. As a kid, I would memorize box office grosses, Billboard music charts, and Amazon’s list of bestselling books. I couldn’t get enough. At dinner parties, I’d ask adults to name a year, and then I’d recite that year’s highest-grossing movie, bestselling book, top-charting song, and the Best Picture winner at the Oscars. (Needless to say, I didn’t have many friends.)

Today, that obsession with culture manifests in new ways: naming the most-followed TikTok accounts, or listing the social platforms with the most monthly actives. I still can’t get enough. Technology has seeped into culture, reinventing how we think of media, and we’re living in one of the most fascinating times for how culture spreads. Media isn’t some stale category; there’s innovation happening across every slice of media. This week, I want to explore some of those innovations.

I’ll focus on five categories of media:

🎞 Film & TV

📚 Books

🎶 Music

🎮 Gaming

📱 User-Generated Content

This piece is far from comprehensive (there’s a lot happening), but I hope it offers a snapshot of how media is evolving in new and creative ways.

🎞 Film & TV

Movies and TV shows get made today in a surprisingly similar fashion to how they were made 50 years ago. Studios and production companies buy the rights to scripts, attach directors and stars, and then hire a vast army of cast and crew to assemble the finished product. Of course, technology has amplified what can be done: Weta, for instance—the special effects company behind movies like The Lord of the Rings and Avatar—has expanded the potential of “movie magic.” (Weta was acquired by Unity last fall, which I wrote about in The Cambrian Explosion of Software and Content.)

But the art of filmmaking still rules. Directors are celebrated for eschewing special effects, winning praise when they use “old school” techniques: say, Christopher Nolan’s car chase scene in The Dark Knight, or Peter Jackson’s use of forced perspective to make hobbits appear small in The Lord of the Rings. Technology has augmented filmmaking, but it hasn’t reinvented it. Technology’s biggest impact, rather, has been reinventing distribution.

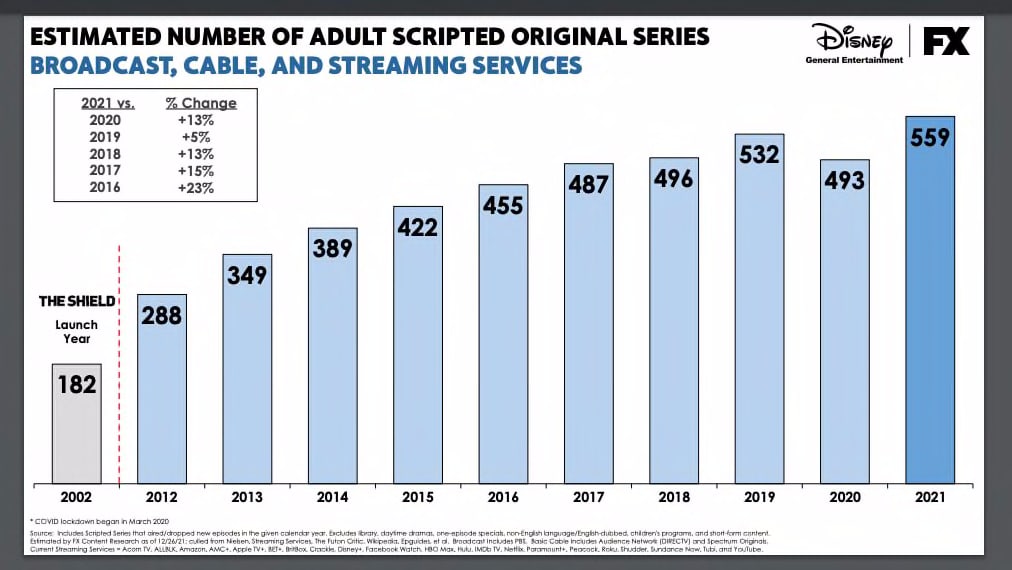

Streaming has led to an explosion in content. “Peak TV” is reaching higher and higher heights: after a pandemic-related decline in 2020, the number of scripted shows on air hit another record in 2021.

Content spend at streamers continues to climb:

To keep up with demand, studios and production companies have to find new ways to streamline operations. One startup helping them do so is Impact, a spinout from Imagine Entertainment that offers a marketplace connecting film projects with cast and crew members.

Film and TV production is an interesting sector for a labor marketplace: workers often work 2-3 month gigs, then return to the market for their next gig. For instance, a cinematographer might work on a Marvel movie, then a Star Wars movie, then finish the year with a big-budget Netflix show. This creates a compelling dynamic for a labor marketplace, with supply returning regularly to the marketplace. Impact streamlines this process of finding work, while also digitizing the pen-and-paper-heavy workflows of a film’s production.

While companies like Impact help facilitate the boom in production, there’s also a need for studios and production companies to better track the performance of their content once it’s out there. Nielsen is the 800lb gorilla in the analytics space, but was built for a previous era of media. New companies like Parrot Analytics bring this field into the 21st-century.

Parrot Analytics offers in-depth data and market measurement. For instance, it can be used to create cool charts like this:

As film and TV become more data-driven—and more measurable—companies like Parrot become more important.

📚 Books

The pandemic has helped revive reading: the average American read 20 minutes a day in 2020, +21% from 2019 and the most since the early 2000s. Print books had their best sales year of the decade in 2020.

In December’s Down With the Gatekeepers, I pointed to book publishers as an example of a classic gatekeeper. Some of history’s best works almost didn’t make it through the publishing gates. I used the example of Dr. Seuss:

Dr. Seuss’ first book was rejected 27 times (!). After the 27th rejection, the author was walking home on Madison Avenue, ready to burn the manuscript in his apartment’s incinerator. As fate would have it, he happened to run into a college friend. And as fate would have it, that day just happened to be his friend’s first day of work at Vanguard Press as a children’s book editor. Dr. Seuss signed with Vanguard the same day, and his book was a massive hit. Dr. Seuss later wrote, “If I had been going down the other side of Madison Avenue, I’d be in the dry-cleaning business today.”

Other great works almost never saw the light of day. Catch 22? 22 rejections. Dune? 23 rejections. The Help? A whopping 60 rejections. Harry Potter is the bestselling book series in history, with 500 million copies sold; it’s the 3rd-most-read book of all-time after The Bible and China’s Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung. But JK Rowling was rejected by 12 publishers.

When you begin to think from first principles, the questions pile up:

Why should we leave human creativity to the whim of one gatekeeper? Why should a book editor decide what gets consumed by the public?

This dynamic is beginning to shift. One author, for instance, used the web3 platform Mirror to raise $88K to write her book. Instead of taking time off work and running down her savings, she proactively earns income to write. Holders of $NOVEL token will share in the profits of her work, in return for believing in her early on.

Books are also being reinvented in how they’re consumed and talked-about. Fable is a social platform for book-lovers—a place to find community around your favorite literature. If horizontal social platforms are splintering into more verticalized offerings, Fable aims to own the book vertical.

That doesn’t mean horizontal platforms are going anywhere: the hashtag #booktok has 44.8 billion views on TikTok.

The distribution of books is also changing. Amazon owns 50%+ of the U.S. book market, but consumer sentiment is shifting to support local businesses. Instead of buying on Amazon, you can buy books on Bookshop, which has an interesting business model: on Bookshop, you can shop directly from a specific local bookstore if you have one in mind; otherwise, your order contributes to an earnings pool that is evenly distributed among independent bookstores (including those not on Bookshop).

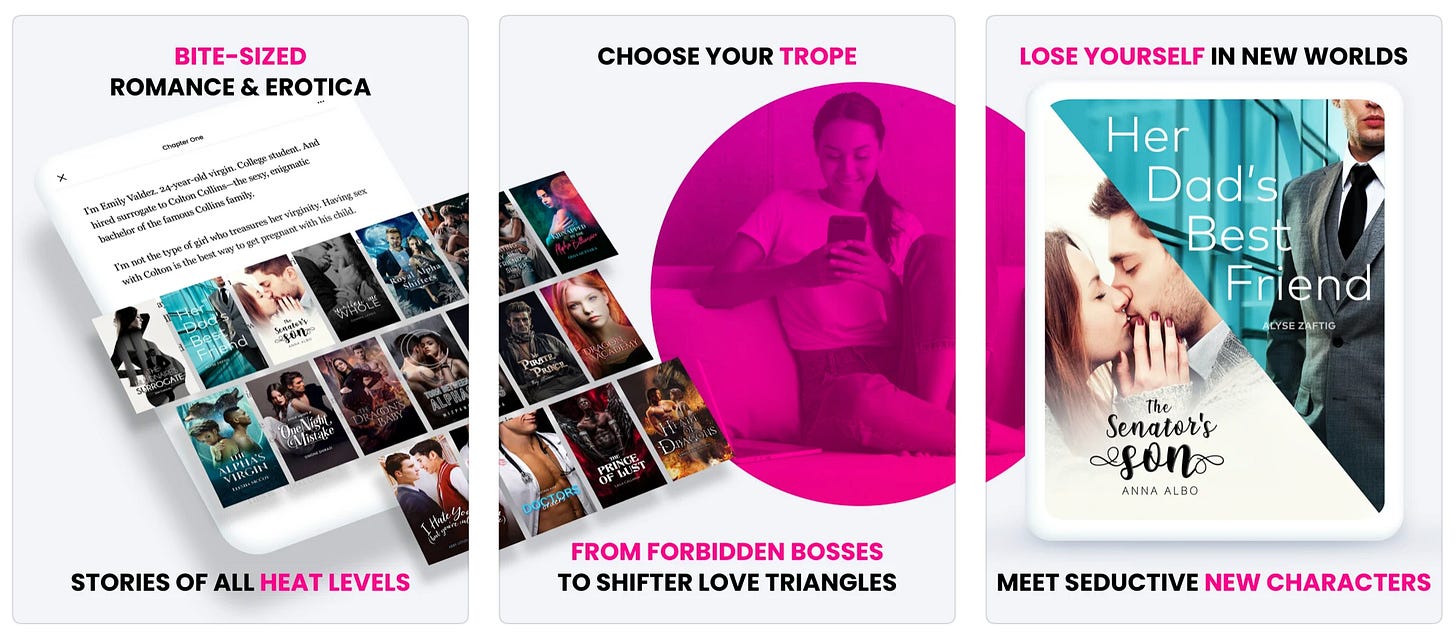

There’s also innovation happening in what a book even is. In China, serialized fiction has been popular for years. Many books are updated daily, with readers paying in bite-sized chunks for the next portion (typically per 1,000 words). Readers are able to give the author real-time feedback: the next “chapter” can incorporate immediate feedback from fans. This model leads to ever-longer books: one of China’s most popular books is ongoing, but has reached 10,000 chapters and is 46 times as long as the entire Harry Potter series. This also leads to compelling economics for authors: a popular serialized fiction author named Zhang Wei earned $15.8M in micropayments.

This model is coming to the West. Radish is a startup that offers “bite-sized fiction,” allowing fans to discover and consume serialized stories in their favorite genres.

🎶 Music

I’ve written in the past about the economics of music. To reuse a flow chart that I’ve used many times (and that I’m pretty sure is out-of-date by now), here’s the economics flow from a $9.99 monthly Spotify subscription:

Artists and songwriters capture very little of the pie. To earn a living wage in the U.S., artists need to generate about 20 million streams every year. My friend Nick DeWilde recently shared a good table to visualize this:

Much of the innovation in music is around helping artists earn more.

Music NFTs, for instance, let artists turn their songs into scarce digital assets. Fans can buy these assets, effectively investing in their favorite artists. Sound, for instance, is a platform that facilitates this and recently passed $1.5M in artist earnings.

Artlist, Epidemic Sounds, and Royalty Exchange let you buy and sell royalty-free music. This creates a valuable new income stream for artists. On Epidemic Sounds, for instance, artists can expect to earn between $1,000 and $5,000 per track. Each quarter, Epidemic divvies up $2M in bonuses to artists, proportional to how their creations perform.

Or artists can turn to Splice to sell royalty-free sounds as component parts—atomic units that can be assembled by other creators into fresh works. The artist Kara Madden (who goes by KARRA) moved to LA to try to make it as a singer. But after a few years, she found herself managing a Jersey Mike’s and making under $10K from music, mostly from singing on My Little Pony commercials. Then she uploaded a pack of vocal hooks to Splice, and made $300K.

Splice costs $9.99 a month and gives users access to 2 million sounds, all royalty-free. It has 4 million users. KARRA’s vocal pack included wordless melodies and hooks like “don't wanna wake up” and “loving you.” David Guetta even used her samples in a song.

In aggregate, Splice has paid out $40M to artists. One board member says: “The music industry of 2017 wouldn’t have found KARRA in a million years. They weren’t looking in the right places for artists with superstar potential.” And in KARRA’s words: “Splice opens the doors for literally anyone to become a producer.”

🎮 Gaming

Gaming is bigger than the box office, streaming video, and recorded music industries combined—and growing much faster.

Gaming has become the largest category of media, with over 3 billion gamers globally.

I’ve written extensively about gaming, so I won’t rehash the space in too much detail. Recent more in-depth pieces include:

But there’s innovation happening across all pockets of gaming: in mobile, led by companies like Dream Games; in blockchain, led by Sky Mavis’s broad suite of companies; and in UGC / modding, led by companies like Overwolf.

📱 Bonus: UGC

The internet, social media, and smartphones have delivered a new form of media: user-generated content. It’s a little bit like cheating to include UGC as its own media category—UGC can be text, audio, video. UGC traverses categories. But UGC is a uniquely internet-native form of content that is inescapable and ever-growing.

UGC continues to proliferate because it’s becoming easier and easier to create. Take CapCut, a little-talked-about editing app that powers many TikTok trends. CapCut was downloaded over 250 million times last year—more times than Spotify.

Or take video editing software like VEED and Kapwing. VEED and Kapwing offer editing tools that are both powerful and accessible. They make it easier for anyone to create high-quality content.

What VEED does for video, Descript does for audio. Editing a podcast on Descript is like magic—I can type in a sentence I want to add, and Descript synthetically generates my voice to speak that sentence. Or, with the click of a button, I can remove vocalized pauses like “um” and “like.”

The list of companies reinventing UGC is long and includes some of the biggest companies in the world: Roblox, Unity, Snap, TikTok, Epic Games’s Unreal Engine. The trend is clear: UGC is the lifeblood of internet platforms and will only grow in volume over time. Technology is making UGC easier and faster for everyone, opening the floodgates to creation.

Final Thoughts

Last fall, I shared the Creator Triad as a framework to think through creator-centric businesses. The Triad had (fittingly) three parts: Creation, Distribution, and Monetization. In other words, 1) how you make stuff, 2) how you get that stuff in front of people, and 3) how you get paid.

Media can be thought of with a similar framework: there’s production, there’s distribution, and there’s financing. Each is being reinvented by technology.

Media is far from an unsexy or unprofitable category. Rather, it’s the way that we consume and create culture. “Traditional” media categories are all being reinvented in radical ways, and technology is creating new categories altogether.

When I think of media transformation, I often think of a Marshall McLuhan quote. McLuhan is the tech philosopher best known for coining the phrase “The medium is the message.” But there’s another McLuhan quote that I revisit more often: “We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.” Media is the way in which we shape society and culture. The companies and products that define the next generation of media will have an outsized impact on how we live, think, and interact.

Sources & Additional Reading

If you’re interested in media, check out Matthew Ball’s essays—they are terrific

For a deeper dive into China specifically, check out Connie Chan’s writing

You can read more about Splice and KARRA here

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: