Instagram's Mid-Life Crisis

Where The App Went Wrong and How to Fix It

This is a weekly newsletter about tech, media, and culture. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, you can subscribe here:

This is the second in a four-part series on consumer social products.

If you missed my piece on TikTok, check it out here. In the coming weeks, I’ll cover Snap and Twitter.

Instagram’s Mid-Life Crisis

In 2010, 800 people visited Trolltunga, a scenic rock formation in Norway. In 2018, 87,000 people visited—an 11,100% increase. What changed? Instagram.

It’s difficult to overstate Instagram’s cultural impact.

Restaurants began to care more about how their food looked. Coffee shops renovated to become more photogenic. “Instagrammable” entered the vernacular.

Entire movements, like the boom in direct-to-consumer brands, emerged on Instagram—and then grew through another nascent industry, influencer marketing. When DTC brands opened brick-and-mortar stores, the stores themselves were Instagrammable; Glossier even built a replica of Arizona’s Antelope Canyon in its L.A. location (below).

Instagram catalyzed the “Experience Economy”. In a survey of Millennials, 80% said they’d rather spend more money on experiences than on things. A Coach bag became an Instagram photo from Coachella.

In what I’ll always view as “peak Instagram”, The Museum of Ice Cream raised $40M at a $200M valuation 🤨

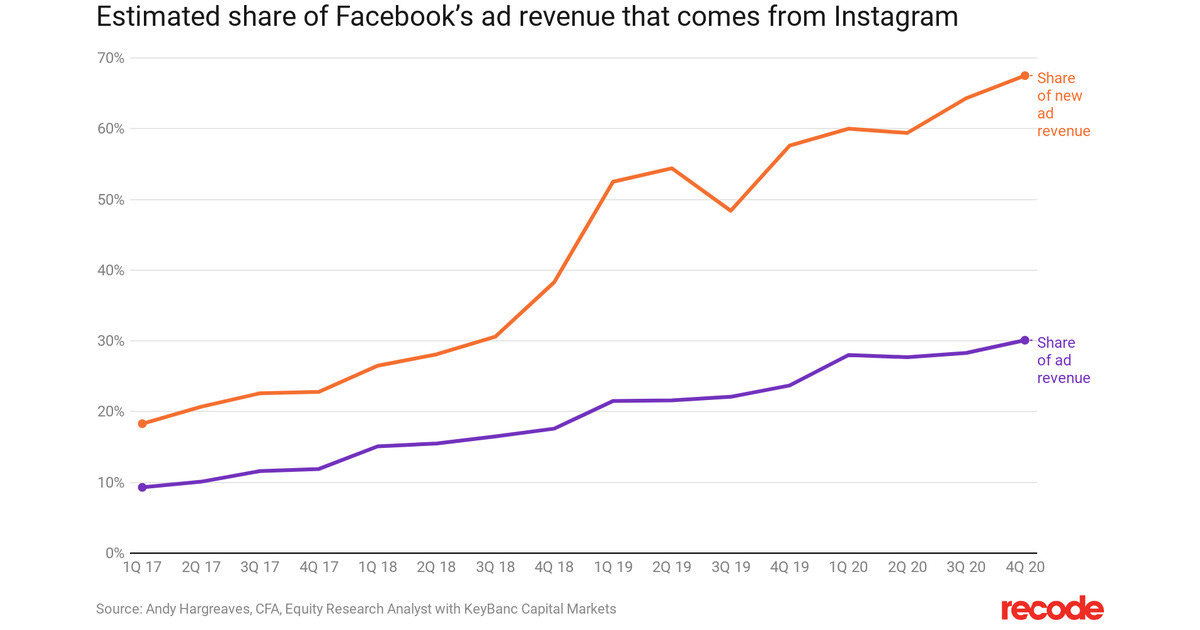

Instagram now has over a billion MAUs and brought in $20B in revenue last year—good for ~30% of Facebook’s revenue and ~70% of Facebook’s revenue growth.

But in recent years, Instagram has become an overcrowded product that builds features without understanding its users. To get back on track, Instagram needs to recognize three things:

Instagram has lost its core value as a product—simplicity—and has become bloated and complicated.

That complexity stems from Instagram trying to be everything to everyone—and most notably, building for the creator rather than the influencer.

Instagram can fix this by rediscovering simplicity and focusing on its biggest opportunity: discovery-driven commerce.

“Simplicity Matters”

Instagram was always about visual simplicity. Back in 2012, when Facebook bought Instagram, Instagram was the elegant antidote to Facebook’s clutter:

Instagram’s founders, Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, were disciplined. All photos were square. There were no hyperlinks. There was no “repost” feature to make posts go viral, like Twitter’s “retweet”. Instagram was minimalist; it was art.

After being acquired, Instagram committed to keeping things simple. In her book No Filter, Sarah Frier writes that Instagram came up with values to insulate itself from Facebook:

[One] was “simplicity matters,” meaning that before any new products could roll out, engineers had to think about whether they were solving a specific user problem, and whether making a change was even necessary, or might overcomplicate the app.

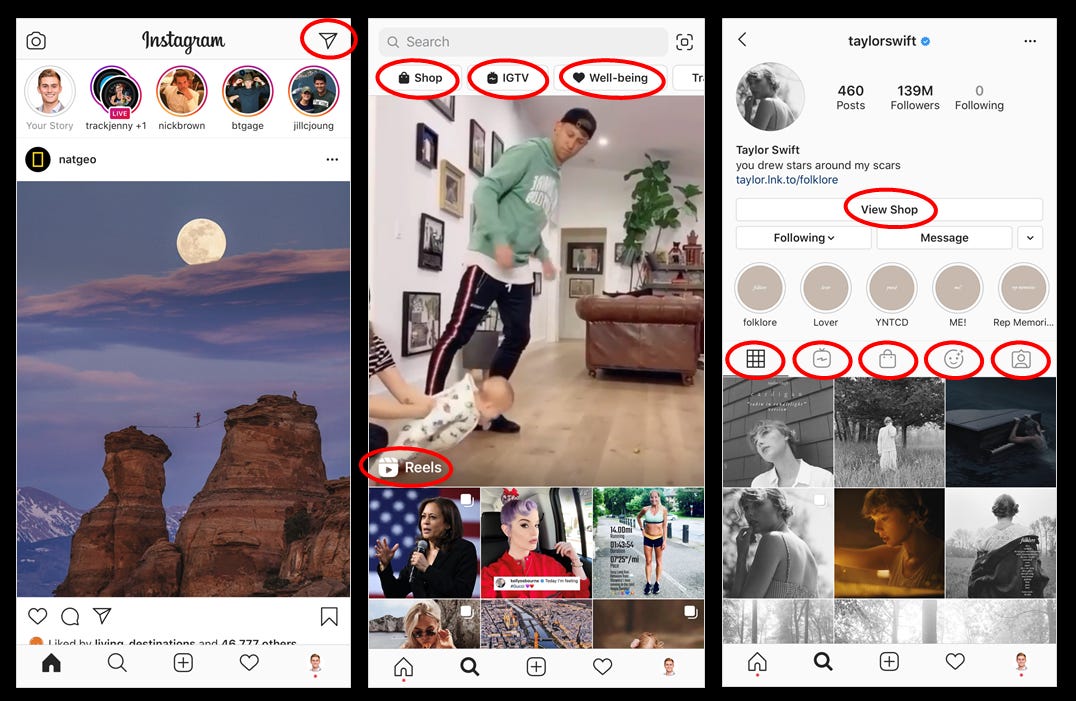

Contrast that with Instagram today:

The app is cluttered with features. Take a look at Taylor Swift’s profile (who I chose for no particular reason other than that I love her). Her posts don’t even appear until halfway down the screen.

Instagram is trying to be everything to everyone. It’s Amazon (Instagram Shop). It’s YouTube (IGTV). It’s Snapchat (Instagram Stories). It’s iMessage (DMs). It’s TikTok (Reels). And that’s not even mentioning its (previous) core feature, in-feed posts.

The irony is that Instagram has become as bloated as Facebook was when it bought Instagram. Meanwhile, new apps like TikTok benefit from their visual simplicity and product discipline.

Reel Talk: Building for the Influencer vs. the Creator

As a product, Reels is an admirable copycat of TikTok. Once you find Reels in the app (which isn’t exactly easy), it pretty much resembles TikTok’s algorithmic “For You” feed.

But while TikTok is the first major consumer product built for content creation, Reels is still built for consumption. Creation features are lacking. There’s no “sound sync” feature. You can’t duet. Reels adds back the friction of creation that TikTok removed.

I’m skeptical that Reels will succeed. Yes, Stories was a massive success and neutralized Snapchat as a competitor; won’t Reels do the same for TikTok? I don’t think so. Stories was adjacent to Instagram’s core purpose: sharing content with friends. It had a social network component. TikTok isn’t a social network, but a content platform. Reels has more in common with IGTV, Instagram’s failed attempt to take on YouTube.

Instagram doesn’t lend itself naturally to creators. In fact, Instagram has always been more for the influencer than the creator. Influencers share a curated, aspirational life; creators are more spontaneous and unfiltered.

A few years back, the Instagram team began to notice an odd trend: many teenagers were using two Instagram accounts. It turned out that teens had “finstas”. A teen’s finsta (short for “fake Instagram”) was a place to be authentic; a real Instagram profile was heavily curated, edited, and contrived.

To its credit, Instagram has taken steps to nullify its reputation as a “highlight reel” for life. Stories have helped. Hiding likes will also help. But the concept of a finsta captures how Instagram is still viewed by millions of users. Instagram got its start as a (literally) filtered version of reality, and it’s difficult to pivot from that.

There are two major trends in social networking, and both are antithetical to Instagram:

There’s a shift toward creators: today’s top online celebrities are raw and deeply personal.

There’s a shift to 1-to-1 and small-group interaction: people are turning to Discord, iMessage, WhatsApp, Telegram, and other platforms to message close family and friends.

Instead of trying to shift its ethos to fit where the consumer social world is going, Instagram should lean in to what it does best. Instagram isn’t a creator platform. It should build for influencers, not creators.

Aspirational, curated content is a natural fit for commerce, and Instagram has an opportunity to be the destination for discovery-driven commerce. Instagram should stop trying to be TikTok and start trying to be Shopify.

Just taking a quick breather to remind you to subscribe if you haven’t already!

Instagram Shop & Discovery-Driven Commerce

Amazon dominates utility shopping. I would even argue that Amazon isn’t shopping, but buying. When you go to Amazon, you (usually) already know what you’re going to get. You search for what you need.

But there’s another type of online commerce: discovery-driven, based on want vs. need. Shopify built the infrastructure layer for this form of commerce, but there’s no platform that dominates the consumer-facing layer. This is the opportunity for Instagram Shop.

In The Anti-Amazon Alliance, Ben Thompson explains how brands struggle with Amazon’s search-driven shopping. Procter & Gamble used to market Tide so that you’d recognize the orange packaging on the grocery shelf. But now, P&G needs a consumer to type “Tide” into the search bar on Amazon. If the consumer types “laundry detergent”, the top hits will be for Amazon’s private-label detergent. Brand recall, as opposed to brand awareness, is much more difficult and expensive for P&G.

As a visual platform, Instagram solves this problem for brands. It’s the next generation of browsing shelves or wandering into a cute mom-and-pop shop.

Shopping on Instagram is still a clunky experience: tapping the tagged CB2 items in the image above brings me to CB2’s website. Instagram doesn’t own the experience. It missed its opportunity to be the end-to-end business-in-a-box commerce platform. If Instagram had moved faster five years ago, it could have built Shopify’s infrastructure.

But Instagram can still be the consumer-facing layer where brands are discovered. Shopify needs this; its own Shop app isn’t a natural place to discover its merchants. This is why Instagram and Shopify are partnering on Instagram Shop, and this is where Instagram should focus its efforts.

Rather than copying TikTok, Instagram should be copying another Chinese-owned app: Xiaohongshu. Xiaohongshu is basically Instagram + Pinterest + Amazon. Xiaohongshu is a commerce-first social media site that owns the end-to-end shopping experience.

Xiaohongshu is the ultimate platform for SMB commerce:

Xiaohongshu operates an online store within the app and there are largely two types of stores. One that is self-operated by Xiaohongshu and the other that is operated by registered brands. Xiaohongshu works as a middleman for brands that are not sizable enough to manage online stores and sell selected goods to its customers. It also accepts licensed brands to register on its online store to directly sell their products. Therefore, Xiaohongshu does not only exist as a bystander selling advertising products to brand sellers but takes active actions to create sales. (Source)

I had the chance to visit Xiaohongshu’s headquarters in Shanghai last year and I was struck by how GMV, not users, is the company’s North Star metric. Xiaohongshu views a take-rate on commerce transactions as a bigger (and more user-friendly) opportunity than running ads.

Instagram Shop can aggregate Shopify’s 1,000,000 merchants in a unified, visual, easily-discoverable storefront.

Final Thoughts

I don’t blame Mark Zuckerberg for launching Reels in Instagram. I’d probably do the same. Facebook’s brand is weak—especially among Millennials and Gen Zs—and Facebook needs to lean on Instagram’s “cool” factor. (Less than a third of Americans know that Instagram is owned by Facebook.)

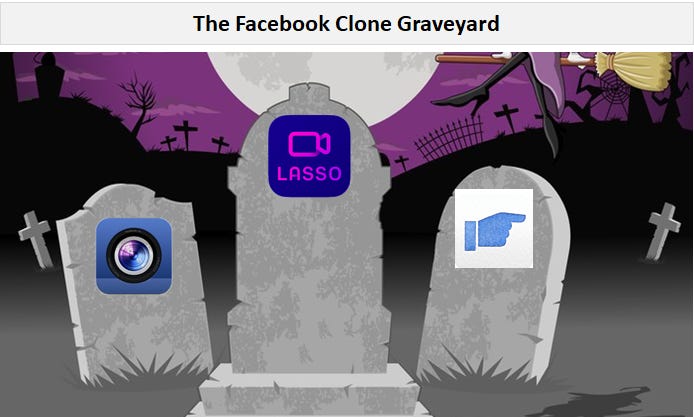

Facebook also has a poor history launching copycat standalone apps. Just ask Facebook Camera (an Instagram copycat), Lasso (a TikTok copycat), or Poke (a Snapchat copycat).

Zuckerberg is leaning heavily on Instagram because he feels forced to, but he’s destroying the app’s value. If Reels gets traction, it should be quickly spun out into its own app. It’s not a natural fit for Instagram and it degrades Instagram’s core feature: simplicity. Worse, it’s distracting Instagram from the opportunity to be a visual storefront for millions of merchants.

As a visual platform, Instagram is uniquely suited to commerce. The lack of a mobile-first, discovery-driven commerce platform leaves an opening. But Instagram needs to strip away excess features, rediscover simplicity, and seize the opportunity.

Sources & Additional Reading—here are the pieces that inspired and informed this content; check them out for further reading on this subject:

No Filter | Sarah Frier

Reels Talk | M.G. Siegler

The Anti-Amazon Alliance | Ben Thompson

Instagram Reels Is a Dud | Taylor Lorenz & Brian X. Chen

Introduction to Xiaohongshu | Nanjing Marketing Group

Chart of the Week

About 40% of the globe remains unconnected to the Internet. Visual Capitalist mapped where the next billion Internet users will come from:

India alone has 685M unconnected people. The opportunity to bring those 685M Indians online is what makes Jio so compelling.

Here’s another good piece on Jio, which has more telecom subscribers than there are people in the U.S. (!) and which, in three months, raised more money than the entire Indian start-up ecosystem raised in 2019.

I hadn’t realized that Jio is “Oil” backwards—a clever nod to the fact that the Ambani’s built their wealth on an oil empire, and are now using that wealth to build a data empire.

Quick Hits

Here’s what to read and what to know from the week:

🎵 A third of TikTok’s U.S. users are 14 or younger.

🌐 Speaking of TikTok: Bill Gates (who is no longer on Microsoft’s board) gave a wide-ranging interview in which he calls social media a “poison chalice”—seeming to suggest that he’s against Microsoft buying TikTok.

📦 In the early months of the pandemic, Amazon struggled to keep up with demand. Negative reviews soared; market share dropped. The company has since recovered—posting record sales in Q2—partly because it invested in 10,000 more ground vehicles and 11 additional planes.

🚗 This piece argues that Ford needs to go private in order to restructure and compete with Tesla. The author points to Michael Dell’s take-private of Dell a decade ago. Ford’s shares are down 40% over the last 20 years; Tesla is up 316% this year.

🧠 Sarah Du has a nice market map of mental health tech companies. This is a space uniquely catalyzed by the pandemic: compounding forces of greater anxiety (demand side) and lowered regulatory barriers (supply side).

🍎 The most interesting news of the week is that Epic Games, the maker of Fortnite, essentially goaded Apple into banning Fortnite from the App Store. Then, Epic dropped an anti-trust lawsuit against Apple and its 30% App Store fee. It paired the lawsuit with a, well, epic video parodying Apple’s famous 1984 Superbowl commercial:

🎮 To understand Epic’s lawsuit, it helps to understand founder Tim Sweeney’s vision. Sweeney has continually lowered the fees Epic Games charges: its licensing fee is only 5% and that’s waived for the first $1M of a game’s revenue. Crazy. This is an effort to grow the pie: with low fees, Sweeney believes gaming can grow into a trillion-dollar industry. Sweeney envisions a cross-platform, real-time virtual world:

“Just as every company a few decades ago created a webpage, and then at some point every company created a Facebook page, I think we’re approaching the point where every company will have a real-time live 3D presence, through partnerships with game companies or through games like ‘Fortnite’ and ‘Minecraft’ and ‘Roblox,’” says Sweeney. “That’s starting to happen now. It’s going to be a much bigger thing than these previous generational shifts. Not only will it be a boon for game developers, but it will be the beginning of tearing down the barriers not just between platforms but between games.”

📁 Jira may be the most-derided work tool. This piece digs into why it’s so hated—basically, it’s built for project managers instead of developers.

🛍️ An interesting McKinsey chart showing what categories have benefited most from the Covid-19 shift to online commerce.

🌆 Here’s the inside story of how activists and the billionaire founder of Blackberry teamed up to end Alphabet’s dreams of building a smart city.

📽️ Sarah Cooper went viral on TikTok during the pandemic for her Trump impersonations. Now, she’s landed her own Netflix special. Another example of how traditional paths to fame are changing: it’s no longer a faceless executive in a skyscraper deciding your fate; anyone now has the opportunity to be discovered. She’s also just really, really funny.

Thanks for reading! To receive this newsletter in your inbox weekly, subscribe here 👇