Internet Niches

Unbundling YouTube, LinkedIn, & eBay; Rebundling Microsoft & Netflix

This is a weekly newsletter about tech, media, and culture. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Unbundling the Internet

There are 2.2 million subreddits on Reddit—online communities dedicated to anything and everything you can think of. There’s one dedicated to trees that look like they’re sucking on things (111,000 members). There’s one dedicated to Nicholas Cage called “One True God” (135,000 members).

If there’s one thing the Internet does well, it’s enable deep, highly-specific niches to form. As the Internet expands, those niches grow and new niches emerge. Growth attracts new companies, creating products and services tailored to the most attractive niches.

Last week, I wrote about the unbundling of the newspaper. Traditional newspapers (The Times, The Post, The WSJ) and first-generation digital media startups (Buzzfeed, Vice, HuffPost) are being picked apart by vertical players. By focusing on one niche, these companies deliver a better product and a better customer experience.

The canonical example of unbundling in the startup world is Craigslist. Craigslist was a Web 1.0 creation and did everything for everyone. Over the past decade, many Web 2.0 startups built valuable businesses by focusing on a specific Craigslist niche:

As niches grow larger and deeper, markets that once seemed unviable for a venture-scale business begin to look more attractive. A horizontal platform, meanwhile, devolves into a jack of all trades, master of none.

Three monoliths being picked apart today are YouTube, LinkedIn, and eBay.

YouTube

YouTube is massive: 2 billion monthly active users watch 5 billion videos a day. Every minute, 300 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube. People watch more video on YouTube each day than on Netflix and Facebook combined.

But YouTube’s scale and variety make it vulnerable to vertical disruptors:

YouTube’s top three categories are music, gaming, and beauty. Spotify is beginning to own the music space (and I wouldn’t be surprised to see music videos premiere exclusively on Spotify within the next few years). Twitch is now the nucleus of online video for gaming.

That leaves beauty. An interesting startup is Supergreat. Supergreat is an online community of real people reviewing beauty products. Supergreat builds on the trend that everyone is an influencer, and it works: beauty is a category built on authentic, trusted recommendations.

A common mistake when a horizontal company unbundles is to fall into the “TAM trap.” The TAM trap is when people underestimate the total addressable market size of a niche. (For example: over a dozen of the vertical companies on the Craigslist graphic above are now doing more in revenue than Craigslist.) You could easily fall into the TAM trap with Supergreat—until you realize that beauty videos get 170 billion views on YouTube each year.

As the Internet grows, niches become larger and deeper. And a vertical player can often unlock more value from a community by providing a better customer experience. Music and gaming both lend themselves to subscription, for example, and Spotify and Twitch have both adopted subscription models. Supergreat unlocks more value by monetizing through commerce—which beauty is uniquely suited to—while YouTube beauty videos still serve ads.

LinkedIn

When I think about the future of work, I tend to break it into three stages:

You learn the skills that you need for a job, you go out and find a job, and then you do the job. LinkedIn touches on all three: (1) LinkedIn Learning provides lifelong learning content; (2) both recruiters and candidates use LinkedIn in the job search; and (3) LinkedIn’s network helps people find and build community to succeed in their fields.

Because LinkedIn is horizontal across both its industries and its services, it’s being picked apart in all three of these stages.

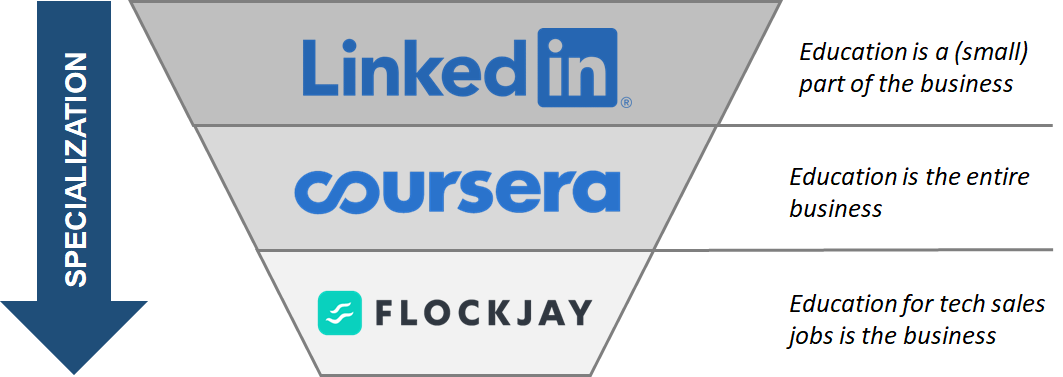

Within the “Learning” portion, companies like Coursera emerged to focus solely on career education. Now, even more specialized startups are unbundling the Courseras of the world. By focusing on one type of learning (Flockjay for tech sales, Lambda School for software development, Microverse for remote international developers), these companies offer a more tailored and valuable product.

LinkedIn’s main functions, though, are #2 and #3: finding a job and networking.

LinkedIn is a sales software company that masquerades as a social network. Of LinkedIn’s ~$8 billion in revenue, about $5 billion comes from subscriptions sold to professional recruiters. Here, LinkedIn is being disrupted by new recruiting software startups like Gem, Handshake, and Yello. These disrupters often compete by starting strong in a niche: Jumpstart, for example, is a Sequoia-backed Series A company that focuses on entry-level roles and on diversity and inclusion.

On the network side, LinkedIn has been peeled apart by new job marketplaces. First came horizontal marketplaces built for the gig economy—TaskRabbit, Thumbtack, Upwork. These marketplaces primarily served blue-collar workers, who had never seen much use for LinkedIn. Blue-collar workers had the benefit of driving high repeat rates on the supply side of the marketplace, which LinkedIn lacked (gig workers come back to the platform often, in search of more work; LinkedIn’s white-collar workers don’t).

Then came vertical marketplaces: Trusted for nurses, Instawork for hospitality workers, RigUp for oilfield workers. By offering tailored products, these marketplaces better serve both the supply and demand sides than their horizontal counterparts. Now, marketplaces are layering on community-building features.

The most interesting companies in the chart above are those in the top right quadrant. They combine the advantages of a vertical marketplace with the benefits of a community hub; both accelerate network effects and improve retention.

Just taking a breather to remind you to subscribe if you haven’t already!

eBay

It’s hard to imagine now, but it once looked like eBay—not Amazon—would be the bigger e-commerce company. Amazon was founded in 1994 and eBay was founded in 1995. For nearly a decade, eBay was more valuable than Amazon. In the mid-2000s, Amazon finally passed eBay in market cap. (Since then, eBay’s stock is up 120%; Amazon’s is up 7,760%.)

One reason that eBay has struggled is that, like Craigslist, vertical companies have picked off its most lucrative niches by offering a better customer experience.

Take GOAT, an online marketplace for sneakers. GOAT was created because its founder ended up with a pair of fake sneakers from eBay. He realized that GOAT could deliver a better service for customers by stamping out counterfeits.

A similar story has happened across eBay’s biggest categories, spawning a variety of multibillion-dollar companies:

In The Rebels Taking on the Empire, I wrote about three startups that took on Amazon and won. While the companies above have unbundled eBay’s peer-to-peer commerce, these three startups have done the same to Amazon in B2C commerce:

By focusing, vertical commerce companies could beat Amazon within their niche. Chewy ($23B market cap) beat Amazon by offering world-class customer service, Farfetch ($9B market cap) by devoting itself to luxury, and Stitch Fix ($3B market cap) by combining data science and personal stylists.

Amazon is fighting back. Just in the past two weeks, Amazon launched both Luxury Stores (a Farfetch competitor) and the men’s version of Personal Shopper (a Stitch Fix competitor). If Amazon bundles these products into Prime, and if they’re “good enough”, Amazon has a shot at stealing some Farfetch and Stitch Fix customers.

The value of Amazon (particularly compared to eBay) is in its price and convenience. Price comes in the Prime bundle. Convenience comes from being a (literal) one-stop-shop. This leads to a key question: at what point do the price and convenience of a horizontal company overpower the added value of a vertical company?

Is Vertical Always Better?

Keeping in mind price and convenience, let’s look at two spaces where unbundling is creating a worse customer experience: streaming video and productivity software.

Netflix is unbundling both by content niche and by content owner:

Services like Crunchyroll focus exclusively on anime, and services like Peacock feature only NBC-owned content. This isn’t good for the average consumer.

First, there’s the price element. Subscribing to multiple streaming services is expensive—and ~90% of people with a non-Netflix streaming subscription also pay for Netflix:

Then, there’s the convenience element. On more than one occasion, I’ve typed a movie title into Netflix on the TV (which takes an absurdly long time because companies haven’t figured out a better way than manually using the remote to type letter by letter 😒), only to find that the movie is no longer on Netflix.

Unbundling Netflix fails the consumer on both price and convenience. And in the long run, the consumer always wins.

Spotify brings you all the world’s music in one location. There are three major record labels in the world—Universal, Sony, and Warner. Would it be better for the consumer if each had their own streaming service? Of course not; that’s the value of the bundle. This is why I think Netflix will rebundle: the also-rans in the “Streaming Wars” will again license their content to Netflix.

Another example is what’s happening in the workplace. Back in July, I wrote The Rebundling of Work and this continues that topic.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Microsoft’s Office 365 and Google’s G Suite dominated productivity software. But over the past decade, more specialized SaaS tools have unbundled Office 365 and G Suite.

This was good. Front’s shared inbox product is a better tool than Outlook for a customer support team. Projector’s presentation software is more flexible and powerful than PowerPoint.

But this proliferation of apps is becoming cumbersome. An Okta report found that the average company in 2018 had 80 installed work apps, an increase from ~50 apps in 2015:

This is creating a need to rebundle work:

Rebundlers take two forms: those that enable a worker to stay organized across apps (“sorting through the noise”) and those that replace apps altogether (“removing the noise”). Companies like Command E and FYI help workers search easily across all their apps. Companies like Notion and Airtable, meanwhile, aim to be all-in-one workspaces that can replace most apps.

For prosumers, more niche SaaS solutions make sense. But for the average company and the average worker, rebundling will improve work’s price and convenience.

This is playing out with Slack and Microsoft Teams: despite launching four years after Slack, Teams now has ~5x as many users. Here, the appeal of a better price (Teams is bundled with Office 365, whereas Slack is another subscription for the business to pay for) and more convenience (fewer apps) trumps the marginal value from Slack’s better product. Even though Teams appeals to a lower common denominator worker, rather than to the prosumer, it wins out.

Final Thoughts

There’s a tradeoff between deep vertical products that better serve niche users and the convenient, one-stop-shop solution of a horizontal product. The best vertical companies create more value for the customer by specializing than they erode through higher prices or lost convenience.

This thesis is still half-baked in my mind—and there’s no “one-size-fits-all” rule here; any rule will vary by industry and use case. But this provides an interesting lens through which to view the next generation of companies that will face verticalization:

Zoom: Will there be a Zoom for education courses, a Zoom for telehealth appointments, a Zoom for business conferences? Or will people prefer a single solution and these verticals will instead run on Zoom?

Shopify: Will there be specialized software for launching an online apparel store vs. an online beauty store? Or will Shopify offer enough value-additive features that it can continue to serve every type of online store?

Airbnb: Will travelers be okay booking a home rental on Airbnb, a camping ground on Hipcamp, and a corporate stay on Sonder? Or will Airbnb’s all-in-one offering win out in the long run?

As the Internet matures, more niches emerge and vertical upstarts become horizontal monoliths. Airbnb peeled off Craigslist’s “rooms / shared” category; now, it faces challenges from vertical players like Hipcamp. What’s more, it was Airbnb’s growth that grew Hipcamp’s niche and made it attractive enough to enter in the first place.

In the end, companies that focus on a niche tend to build better products and to deliver better customer experiences. That fuels growth and a small niche becomes a massive, broad market. New niches are born within it, new disruptors emerge, and the cycle repeats.

Sources & Additional Reading

Check these out for further reading on this subject:

The Four Myths of Bundling | Shishir Mehrotra

Unbundling Craigslist | CB Insights and the iconic chart by Andrew Parker

Bundles 2020 | Ben Thompson

LinkedIn Is The New Craigslist | David Sacks

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox weekly: