Krispy Kreme, Crocs, and Keeping the Main Thing the Main Thing

Lessons from Business Turnarounds

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Krispy Kreme, Crocs, and Keeping the Main Thing the Main Thing

When I was 12, I bought my first stock. On my birthday, my dad told me that the U.S. government ran a program that granted every 12-year-old $100 to invest in the stock market. In hindsight, I realize that this was most definitely not a federal program; rather, it was my dad’s surreptitious way of getting me excited about investing. Clever.

Being 12 years old, I immediately invested the entire $100 into a single company (diversification be damned!) and chose my favorite company: Krispy Kreme Doughnuts 🍩

My timing was impeccable:

Shortly after investing, Krispy Kreme’s stock price cratered. It was a tough lesson for 12-year-old Rex 🥲

But as the chart above shows, after weathering a long winter, Krispy Kreme has had a stunning comeback. What happened, exactly? In short, the company got ahead of its skis in the 2000s. People loved Krispy Kreme for its promise of “Hot Doughnuts Now”, emblazoned on neon signs in front of stores.

But under pressure to grow, Krispy Kreme began manufacturing its doughnuts in central kitchens, trucking them to stores, and selling doughnuts in 7-Elevens. The company became less associated with hot, fresh doughnuts than with cold, stale products on gas station shelves.

There’s an aphorism in business I’ve always loved (I believe it traces back to Stephen Covey originally): “The main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing.” Krispy Kreme strayed from the main thing, and consumers punished the company for it.

There were other contributing factors, of course. The mid-2000s saw the boom of the low-carb Atkins diet; Krispy Kreme corporate was predatory with franchisors; there were some shady accounting practices. But the key driver was that Krispy Kreme lost sight of what made it special.

I’ve always been fascinated by business turnarounds—it probably has something to do with that painful first investing experience—and this lesson of “the main thing” comes up again and again. Take Starbucks, which had its own rough patch in the late 2000s. In response, Howard Schultz refocused Starbucks on making great coffee with great service. He said at the time, “Starbucks is not a coffee company that serves people. It is a people company that serves coffee.”

In 2008, Schultz closed Starbucks stores for a day to retrain baristas in making the best espresso. (That move cost the company an estimated $6 million.) Schultz then upgraded espresso machines worldwide to the Swiss-made Mastrena, decided to only deliver whole-bean coffee to stores, and required baristas to grind beans in-store. Any coffee sitting around for more than 30 minutes was instructed to be thrown out. Schultz also decided that the aroma of sandwiches had begun to overpower the smell of coffee, so he shut down the entire sandwich operation. (Sandwiches later made it back into stores.) The bottom line was: focus on great coffee—the main thing.

Another “main thing” example comes from one of my favorite business turnarounds—and one of the most underrated. It’s the story of Crocs over the past few years.

In 2021—19 years into the company’s life—Crocs revenue grew 67% (!) to $2.3 billion. Profit margins in 2021 improved from 22% to 31%. This followed nearly a decade of flat sales and stagnant margins.

Some of 2021’s growth stemmed from a COVID-induced boom in comfort wear, sure, but much of it came from renewed focus. In 2020-2021, Crocs trimmed its product selection by 30-40%, which helped the company improve margins and refocus marketing efforts on its iconic clogs. Keep the main thing clog the main thing clog.

Crocs also announced that it would close all 558 retail stores, shifting entirely to e-commerce.

There are other interesting lessons to draw from Crocs—

First, we live in an era of self-expression on social media. People crave personalization. Crocs doubled down on Jibbitz, little charms that let people customize their Crocs. All of a sudden, Crocs became a vehicle for showcasing personality and uniqueness.

People went crazy for it. Jibbitz are quirky and fun—you can even put little Crocs on your Crocs because…why not? 🧐

Alongside refocusing on its marquee clog, Crocs went all-in on collaborations. The goal was to inject coolness into the brand through affiliation. There were partnerships with Justin Bieber and Post Malone, with Diplo and Balenciaga, with Hidden Valley Ranch and KFC. You could even buy breakfast cereal Crocs—

Collabs cut through a noisy internet with viral moments and massive earned media value. Crocs—shockingly—became trendy.

But I digress. The common denominator of the turnarounds at Krispy Kreme, Starbucks, and Crocs was a renewed focus on the main thing. Another way I’ve heard it phrased in the startup world: “Keep it simple, stupid.” Don’t forget what your business stands for.

In these examples, the main thing was a product. Fresh doughnuts. Good coffee. A gelatinous hole-filled shoe. But the main thing doesn’t need to be a product; sometimes, the main thing is a guiding mission. Three examples—

For Amazon, the main thing is customer obsession. The company has been able to translate that single value proposition into dozens of disparate product lines, from e-commerce, to grocery, to streaming, to cloud services.

For Disney, the main thing is great content. In 1957, Walt Disney famously sketched out his company’s strategy by hand. It centered around content, with content fueling theme parks, merchandising, and so on.

Sixty-five years later, little has changed. Content is still the engine that powers Disney’s flywheel. A few years back—in an ill-fated effort to get a meeting with my business hero, Bob Iger—I sketched out an updated version of Walt’s drawing. Rather than theatrical films being the nucleus, Disney+ now takes center-stage. But both rely on great content, only delivered through different mediums.

Iger’s prescient acquisitions—Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm, and 20th Century Fox—were savvy because they brought IP into the House of Mouse that would then fuel generations of great content. Disney is excellent at keeping the main thing the main thing.

As a final example, for Costco the main thing is low prices. Every aspect of Costco’s business revolves around keeping prices low.

Costco did $227 billion in sales last year, making it the 2nd-largest retailer in the world after Walmart. And yet, Costco makes almost $0 in profit from product sales, essentially selling products at cost. Instead, Costco charges a membership fee that’s almost pure margin. Costco has 120 million people paying $60 a year just for access to its stores. Over 1 in 4 U.S. households has a Costco card.

People pay for membership because Costco offers those unbeatable low prices. And low prices bring in more members, which boosts revenue. Huge sales volume gives Costco leverage with suppliers, leading to even lower prices. The cycle repeats.

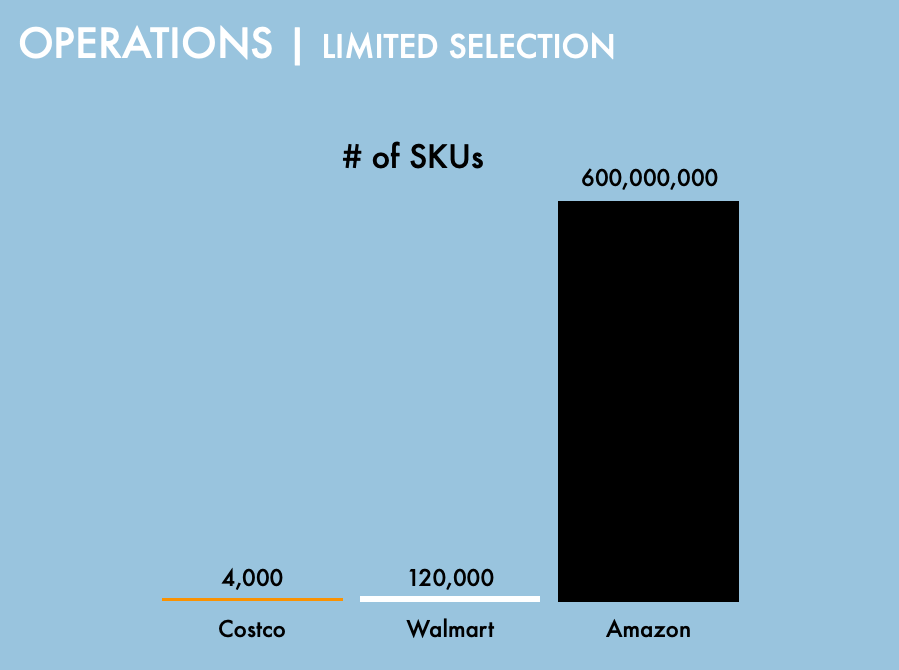

Costco keeps its own costs low by offering limited selection. Costco offers 4,000 products compared to Walmart’s 120,000 and Amazon’s 600,000,000. Customers get one choice of ketchup, one choice of shaving cream, and so on.

This means Costco is often a supplier’s largest customer, giving Costco leverage to source products at the best costs. Fewer products also means less complexity, allowing Costco to be more productive and profitable per employee ($12K in profit per employee, 3x more than Walmart’s $4K in profit per employee).

Costco sells in bulk, which makes people buy more while thinking they're getting a great deal. Selling in bulk also has the added benefit of making it harder to steal things—seriously: Costco only loses 0.2% of revenue to theft each year, 80% lower than Walmart.

Costco’s cavernous stores double as its warehouse. Forklifts take products from the delivery truck to the store floor, dramatically cutting labor and real estate costs.

Costco has been so successful over the years—as other brick-and-mortar retailers have struggled—because it remains laser-focused on low prices. Its former CEO says, “Many retailers look at an item and say, I’m selling this for $10. How can I sell it for $11? We look at it and say, How can we get it to $9? And then, How can we get it to $8? It is contrary to the thinking of a retailer.”

To close with one fun anecdote that drives the point home:

Costco’s CEO once went to Jim Sinegal, the founder of Costco, and said: “Jim, we can’t sell our hot dogs for a buck fifty. We’re losing our rear ends.” And Jim said to him: “If you raise the price of the f*cking hot dog, I will kill you.”

Final Thoughts

Companies often lose sight of the main thing because of pressure to grow. This was especially true in the last decade, with the market rewarding growth over profitability. There are dozens of examples of startups that strayed from their bread-and-butter.

Uber got distracted by expensive self-driving car efforts, which kept the company from nailing the unit economics underlying its core business. Google got distracted by its many moonshots (RIP Project Loon), which it could afford because of its cash cow core business but which led to bloat and complacency in search. And can anyone seriously say that Meta remains committed to its mission statement of ‘bringing the world closer together’? The company is so focused on competing with TikTok that it has lost its ability to a) innovate without acquisition, and b) facilitate true connection.

Of course, there’s a tradeoff between a focus on the main thing and a lack of innovation. Companies still need to invest in R&D and to experiment, particularly to evade the innovator’s dilemma. But experimentation shouldn’t come at the expense of degrading the core product. Many companies, over time, take their eye off the ball in search of the next big thing.

In this current market environment, with many companies facing slowing growth and rising costs, these stories offer good reminders: focus on what makes you great, keep it simple stupid, and keep the main thing the main thing.

Sources & Additional Reading

Krispy Kreme Fell Apart Then Came Back | Entrepreneur

Starbucks Turnaround | WSJ

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: