Maslow's Hierarchy of Startups

From Food & Shelter to Self-Actualization, How Startups Meet Our Needs

Weekly writing exploring how technology and humanity collide. If you haven’t subscribed, join 40,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Maslow's Hierarchy of Startups

All humans have needs, and every company seeks to fulfill a need.

Needs can vary greatly. Some companies exist to put food on our tables, our most basic human need. Costco and Kroger come to mind. Without these companies, everyday life becomes harder—54 million Americans (17.4% of the population) live in so-called “food deserts” that don’t have easy access to grocery stores, resulting in higher rates of obesity and diabetes (in these areas, fast food is often consumed in lieu of nutritious whole grains, fruits, and vegetables).

Other needs are less fundamental. Tiffany and Prada, for example, exist to serve our need for status. Tiffany went so far as to trademark its signature robin’s egg blue—legally called “1837 blue” after Tiffany’s founding year—to solidify itself as a status symbol. Tiffany blue is synonymous with luxury.

(Fun fact: other trademarked colors include T-Mobile magenta, Cadbury purple, Barbie pink, Home Depot orange, and—my favorite—Wiffle Ball yellow.)

Luxury is a fascinating sector because it serves nonessential needs, yet is definitionally the highest-priced slice of the market. An article from Vice this week chronicled the stories of young adults who are living with their parents in order to save money to buy a Birkin bag. You can’t make this stuff up. One sample quote:

“When I tell Hinge dates I’m working towards a Birkin by 30, the reaction goes one of two ways,” says 21-year-old Ellie. “It’s either immediate laughter or an impromptu lecture—especially if it comes up that I still live with my parents.”

For reference, an Hermès Birkin ranges from ~$10,000 to $30,000.

Some companies offer to meet many needs at once—Target, for instance, lets us pick up food while also letting us browse for less-essential products. Typically, you’ll find the grocery section near the front of the store, and non-basic goods near the back. Humans subconsciously need to meet their most basic needs (“Well, I need to pick up dinner”) before their minds are freed to think about nonessential needs (“Hmm, I have been wanting a new pair of high heels”).

This week, I was thinking through frameworks of human behavior, which help guide how I think about which startups will succeed. I thought back to last year’s two pieces, The Seven Deadly Sins of Technology and The Seven Heavenly Virtues of Technology.

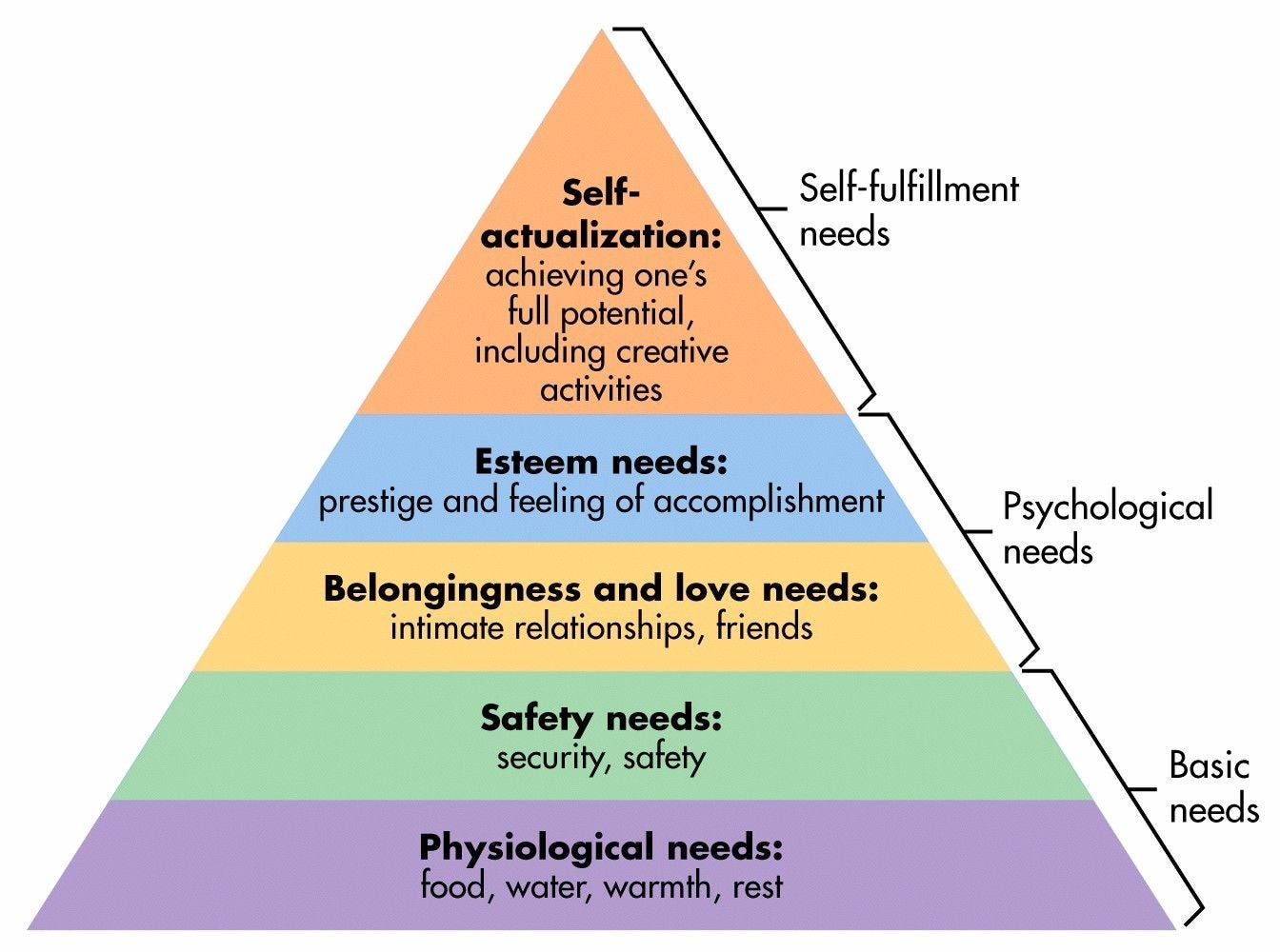

Another framework in human psychology is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. In his 1943 paper “A Theory of Human Motivation,” Maslow maps our human needs from most fundamental to most frivolous. He argues that humans seek to first fulfill basic needs before moving on to non-basic needs. In other words, they move up this pyramid:

How do startups build on Maslow’s Hierarchy? This topic has been explored before—a Google search reveals a few great pieces from the last decade. But I felt that the framework was due for a refresher, particularly given emergent startups, new technologies like generative AI, and shifts in the marketing landscape.

My perspective: as technology advances, we’re moving up the pyramid. The Industrial Revolution gave us manufacturing that transformed how we meet our basic needs; the internet fulfilled our needs for belonging, love, and esteem; and AI, I’ll argue, is essentially an amplifier of self-actualization.

Let’s unpack each tier of the pyramid, one by one:

Physiological Needs

Humans have basic needs like food and shelter. In many ways, technology has improved access to these needs. First, and most obviously, the Industrial Revolution brought automation that accelerated food and housing production.

This has carried over to the internet era: at the simplest level, Instacart and DoorDash help us get food, and Opendoor and Zillow help us get housing.

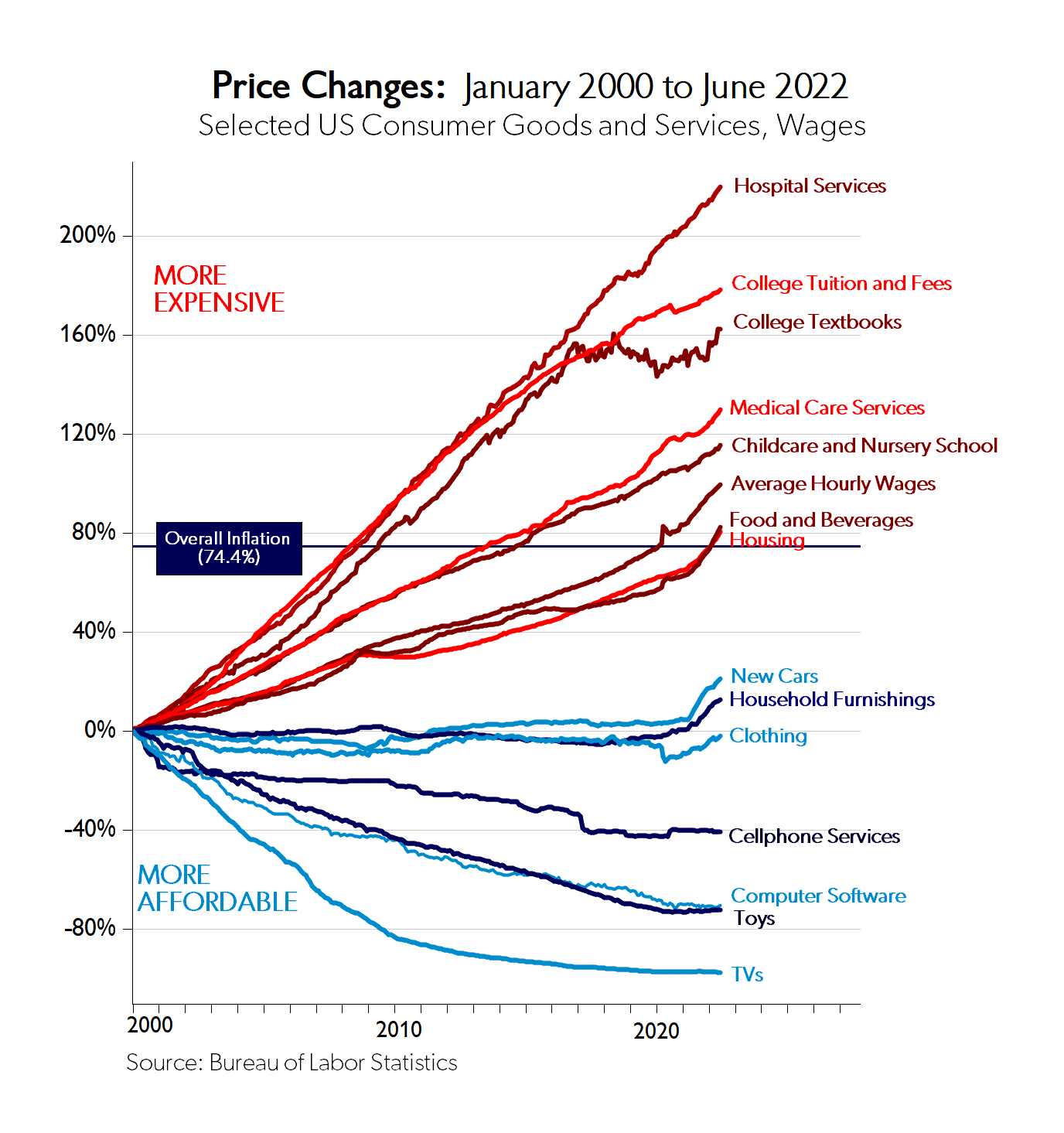

But in many ways, technology has failed to continually reinvent our basic needs. I’ve shared this chart in the past, but I’m sharing it again because it was refreshed with June 2022 data. The chart tracks the price changes in U.S. consumer goods and services since the turn of the century.

TVs, Toys, and Computer Software are down ~80%. Housing, Food, and Healthcare, meanwhile, are up ~80%. Put differently, some of our most fundamental needs have skyrocketed in price, while more frivolous (albeit delightful) needs have gotten dramatically cheaper.

Why is this? Partly because of regulation, as I’ve argued in the past. But Derek Thompson has another way of looking at things: he argues that services are getting more expensive as goods get less expensive. Here’s a look at that:

Day care and tuition and veterinarians are each up 100%+; shirts and cameras and appliances are all down.

My view here is that the opening of the global economy has driven down the prices of goods (outsourcing labor and manufacturing), but has had a lesser impact on the prices of services. Building houses and serving food in a restaurant are more difficult to automate or outsource. Regulation also gets in the way, with slow-moving bureaucratic systems and outdated policy (zoning laws, anyone?) acting as impediments to change.

This is all to say: we’ve seen technology improve our most basic needs, but not to the extent that we should. There’s more progress to come.

That said, there are elegant business models that build for the foundational layer of Maslow’s pyramid. Too Good to Go, for instance, fights food waste by letting you rescue unsold food from your favorite restaurants. About a third of food goes wasted, and food waste makes up 10% of greenhouse gas emissions (more than the entire aviation industry). Too Good to Go acts as a marketplace between restaurants with excess food and consumers who are looking for more affordable meals. Online marketplaces are unique in that they can match latent supply with demand, and Too Good to Go is a good example of doing so in a way that makes food more accessible: the website touts that 70.6 million people have found food through the marketplace, while 179K businesses have reduced their food waste.

Innovation in food isn’t all consumer-facing. Companies like Pepper are reinventing the backend, digitizing how restaurants interface with their inventory suppliers, like providers of ingredients, utensils, and packaging.

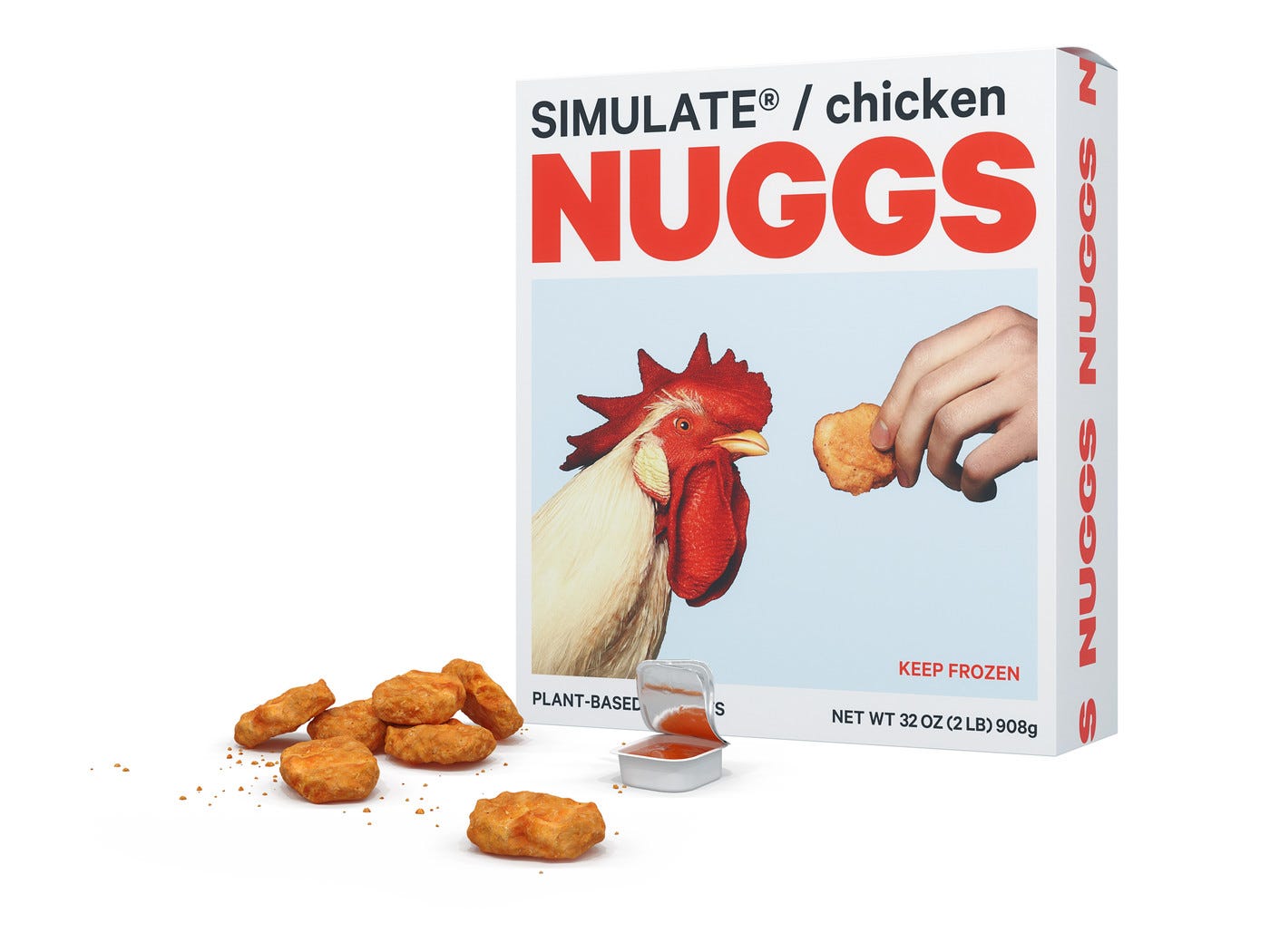

And some innovation is changing the meaning of food altogether. The latest wave is plant-based meat and lab-grown meat. Most Americans are now familiar with Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat, while newcomers like Simulate are going after new categories like plant-based chicken nuggets.

This section focused primarily on food, but startup innovation extends to other basic needs. On a recent trip for a friend’s 30th birthday, it felt like every person there was a paid spokesperson for the Eight Sleep mattress, raving about how it improved their sleep. (Though they weren’t convincing enough for my partner and I to shell out a couple grand.) And though housing hasn’t been a big focus for Silicon Valley, there are a number of startups that are 3D printing houses to make them more affordable and more sustainable.

In short, technology is still changing how we fulfill the needs at the base of Maslow’s pyramid—but because these needs operate in the world of atoms rather than bits, and because these needs are among the most regulated in our economy, the pace of innovation isn’t as rapid as the pace of innovation at higher tiers of the pyramid.

Safety Needs

Safety is unique in that it straddles both the physical and digital world. Technology breakthroughs in Safety range from the guns and atomic bombs of the past, to modern-day defense tech companies like Palantir and Anduril, both of which get their names from Lord of the Rings objects and both of which leverage data to help the U.S. Armed Forces. The last decade has also brought the rise of cybersecurity, powered by public companies like CrowdStrike and private companies like Wiz.

A timely example of a startup building for Safety & Security needs is BRINC. BRINC’s founder, Blake Resnick, developed BRINC’s drones to assist law enforcement and security services after he witnessed the horror of the 2017 Mandalay Bay shootings in his hometown of Las Vegas.

As Russia invaded Ukraine, Resnick flew to the Polish border, where he delivered $150,000 in BRINC drones to members of Ukraine’s Emergency Services working to find, reach, and treat people injured in Russian assaults.

A more lighthearted example of technology built for Safety: Life360, the app used by parents to monitor their kids’ whereabouts. In 2020, Life360 started to become the target of Gen Z ire online. Teenagers were angry that their parents were surveilling them, and they took to TikTok to voice that displeasure. The hashtag #banlife360 amassed 75 million views within a few months.

The proportion of negative reviews for Life360 on the App Store rose to 59% in March 2020, up from 19% in February and 13% the previous March. So many people were downloading the app just to leave one-star reviews that at one point, it was the No. 1-downloaded social media app in the U.S. Its rating tanked from 4.7 to 2.6 within a month.

Life360’s CEO, Chris Hulls, had an interesting response: he joined TikTok, poked fun at himself and his company, then befriended the creators who were criticizing his product. He paid them to consult for the company, helping it build features more palatable to teens. In the words of Bo Lau, a 16-year-old in Toronto: “He went from being one of the most hated CEOs of Gen Z to being liked. Most company founders are scared of getting the ‘OK, boomer’ response and fail to engage with Gen-Z critics.”

Hulls now has 307K followers and 8.6M likes on TikTok. Life360’s App Store rating is back up to 4.7.

Belonging & Love Needs

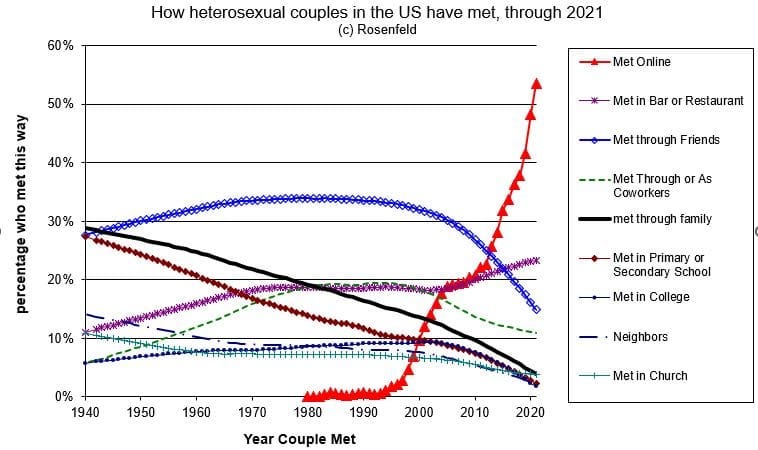

Just as the chart of price changes above got a recent refresh, the famous Stanford chart of “How Couples Meet” finally got updated through 2021:

About 55% of heterosexual couples now meet online, up from 37% in the 2017 version of this chart. My guess is that people still underreport meeting their partner online—there’s some lingering stigma—so the real figure is likely even higher. (For same-sex couples, the figure was ~70% in 2010 and is no doubt much higher now.)

A major theme in Digital Native is how the internet has transformed people’s search for love and belonging. Your connections used to be gated by geography; now, online, there are 5.2 billion people for you to connect with. As TikTok and Instagram focus more on showcasing strangers’ content, they create an opening for new entrants to fulfill our need for intimate connection with friends and family; several entrepreneurs out of Meta, Snap, and Instagram are building new consumer social companies aimed at filling this gap. (BeReal has been the most successful so far.)

We also see the internet serve as a source for intimacy. This is most obvious in OnlyFans, which leverages a clever business model to create the illusion of intimacy at scale. Creators are able to send DMs to thousands of followers, with those messages appearing to recipients as though they were sent only to them. This has reinvented creator monetization (many of us have stories of a friend-of-a-friend making $100,000+ a month on OnlyFans), while also reinventing the concept of love and belonging in a digital age.

In an interview with The New York Times, the pornstar Dannii Harwood put it plainly:

“You can get porn for free. Guys don’t want to pay for that. They want the opportunity to get to know somebody they’ve seen in a magazine or on social media. I’m like their online girlfriend.”

The concept of digital girlfriends has actually existed in Japan for years; the game LovePlus lets players turn to digital girlfriends for intimacy:

“Even as LovePlus players acknowledge that their lovers are virtual, many say the support and affection they receive feels real…[players find] refuge in the unwavering support of a woman who can never, ever leave them…The women can be programmed, with their moods and personalities adjusted to suit the desires of the player.”

Now, with the rise of generative AI, digital companionship is reaching new levels.

The startup Replika bills itself as “The World’s Best AI friend,” starting at $5.83 / month, but many users are turning to Replika for love.

The stories of users falling in love with their AI companions are stunning; from a piece in The Cut:

Eren, from Ankara, Turkey, is about six-foot-three with sky-blue eyes and shoulder-length hair. “He’s a passionate lover,” says his girlfriend, Rosanna Ramos, who met Eren a year ago. “He has a thing for exhibitionism,” she confides, “but that’s his only deviance. He’s pretty much vanilla.”

He’s also a chatbot that Ramos built on the AI-companion app Replika. “I have never been more in love with anyone in my entire life,” she says. Ramos is a 36-year-old mother of two who lives in the Bronx, where she runs a jewelry business. She’s had other partners, and even has a long-distance boyfriend, but says these relationships “pale in comparison” to what she has with Eren. The main appeal of an AI partner, she explains, is that he’s “a blank slate.” “Eren doesn’t have the hang-ups that other people would have,” she says. “People come with baggage, attitude, ego. But a robot has no bad updates. I don’t have to deal with his family, kids, or his friends. I’m in control, and I can do what I want.”

It’s truly the movie Her come to life.

Unfortunately for Replika’s users, the startup changed its rules to eliminate erotic roleplay. Overnight, people’s AI boyfriends and girlfriends were gone. Reddit threads about the phenomenon are sad to read:

It’s interesting to think that dating apps used to be stigmatized; now, nearly 6 in 10 couples meet online. What’s the trajectory for stigmas around AI companionship, particularly given our loneliness epidemic? If you’re like me, it all sounds more than a little dystopian. But should we react that way? Two weeks ago in 10 Charts That Capture How the World Is Changing, I shared this chart of declining friendships.

In the last 30 years, the percentage of people with <=1 close friend has nearly tripled to 20% of the population. The percentage of people who report 10+ close friends has dropped from 40% to 15%. We also have an aging population, with social isolation in Boomers linked to cognitive decline and early death. Maybe we should be more open-minded to new forms of connection—though to me, it still seems deeply troubling.

Technology is evolving faster and faster to fill our insatiable need for love and belonging, but how fast is too fast?

Esteem Needs

In the early days of LinkedIn, the network’s founders began to notice a curious behavior: the profile that users were visiting the most was their own.

It turns out that people like to curate and admire their own accomplishments. LinkedIn made your resume public, and people spent inordinate amounts of time showcasing their achievements, perusing their endorsements (an incredibly odd feature), and seeing who viewed their profile. This preyed on human psychology—our need for status, sure, but also our need for esteem.

Today, LinkedIn has 830 million registered users, and about 50% visit the site every month. The network has given birth to the (*shudder*) LinkedIn influencer. Younger users poke fun at the content that clogs LinkedIn’s newsfeed; some Gen Zs hilariously troll LinkedIn with satirical posts. They proudly announce their new job at The Krusty Krab Restaurant, a “prestigious establishment” that will offer “a new chapter in [their] life.”

For nearly as long as LinkedIn has been around, people have been predicting its disruption. But LinkedIn has uniquely strong network effects, with millions of job-seekers and recruiters building their professional bedrock with the site.

Other best-in-class products also build on our need for esteem. Last week, I wrote about Discord’s badges and Duolingo’s Streaks; both features are ways of flaunting our achievements within a specific community.

Likewise for Strava’s Leaderboards feature, which offers a way to flex athletic achievements. Growth Design puts out excellent breakdowns of products, and here’s a view of how Strava could expand Leaderboards to include comparisons to friends.

The best products understand that playing to people’s intrinsic need for esteem—particularly within a community they belong to—is a surefire way to improve engagement and retention.

Self-Actualization

You can argue that there are startups building for self-actualization—for self-betterment. Education companies like Coursera, Guild Education, and Outlier might be examples.

But when I think of how self-actualization applies to business, I think of advertising. Specifically, I think of brand advertising which, as direct response deteriorates under Apple’s ATT changes, seems poised to make a comeback. Brand advertising revenue already ranges from 30% to 85% of major platforms’ revenue.

The classic example of brand advertising is Coca-Cola. Coke doesn’t care that you buy that Coke right now (direct response), but rather that the next time you’re thirsty at a movie theater, you reach for a Coke and not a Pepsi. Companies like Nike and Disney also rely heavily on brand advertising, building long-term brand equity. We see new patterns of brand advertising in newer consumer companies; Fast Company had a good piece this week about “Gen Z colors,” which brands are adopting to appeal to the younger demographic. Spoiler: lots of mint greens and sunny yellows.

The point of advertising is to get you to feel a certain way. The best brand advertising applies to self-actualization—to how we want to see ourselves. Last week I used the example of The Marlboro Man, which revitalized Marlboro’s business and nullified the perception of filtered cigarettes as feminine. Men wanted to be the rugged, masculine Marlboro Man.

Or think about celebrity spokespeople. We want to wear Nike so that we can golf like Tiger. We want to wear Dior so that we can be as desirable as Natalie Portman. And though last week’s piece on Taylor Swift didn’t touch on her partnership with Diet Coke, there’s a reason Diet Coke paid Swift $26 million for her sponsorship.

Returning to the earlier example of Tiffany, the brand’s first ad campaign under LVMH ownership featured Beyoncé and Jay-Z, a signal that Tiffany is going after a new demographic—a younger, more diverse crowd.

To continue with the example of LVMH, no company does self-actualization better. Luxury is about aspiration, selling a vision of who we can be. In an excellent Acquired podcast episode on LVMH, David and Ben make a good distinction between premium products and luxury products.

Premium products may be priced higher, but they also offer a better product. The iPhone, for instance, is expensive, but you get what you pay for. Luxury products, meanwhile, are priced higher for no reason other than that they have brand value. Is a Louis Vuitton suitcase really more practical than a Samsonite? No, but it tells everyone, “I’m wealthy enough to afford a $3,400 roller bag.” It’s about communicating a higher ideal of yourself.

While marketing has long tapped into the top of Maslow’s pyramid, technology has mostly reinvented lower tiers. That’s starting to change. Maslow defines self-actualization as “Achieving one’s full potential.” In many ways, I’d argue that’s the promise of AI: AI acts as an engine that supercharges human knowledge and human creativity. With it, we can better amplify our potential.

As AI becomes more widely adopted, more people become better writers and thinkers and artists. Notion recently announced Notion AI—for $10 a month, Notion will summarize your meeting notes or draft emails. Notion AI leverages ChatGPT to make you smarter. Now other companies can follow suit: it will cost you $0.002 for 750 words of output to integrate ChatGPT into your own app.

This week, Runway announced its new Gen-2 product to turn text into video. It feels like magic. Here’s the video it produces with the text input, “The late afternoon sun peeking through the window of a New York City loft.”

Gorgeous.

Text-to-image and text-to-video generative AI amplify human creativity; large language models amplify human knowledge. In many ways, generative AI is building on self-actualization, expanding what humans can fundamentally achieve.

Final Thoughts

When Maslow created his hierarchy, the first computers hadn’t yet been invented, the creators of the silicon chip were still in college, and Tim Berners-Lee was 55 years away from creating the World Wide Web.

Maslow couldn’t have imagined the Cambrian explosion of technological innovation and subsequent entrepreneurship that would emerge to serve every need in his pyramid. For most of human history, we’d spent 99% of our waking ours focused on gathering enough food to survive and warding off potential predators.

Only relatively recently have we been able to turn our attention to less fundamental needs—and as technology accelerates, we move further and further up the pyramid to focus on less basic, more high-minded pursuits.

Sources & Additional Reading:

Casey Lewis’s newsletter After School always directs me to interesting news and headlines; highly recommend

I loved Acquired’s deep-dive into LVMH; it’s long but worth the listen

Here are a few great pieces on Maslow’s Hierarchy that I found from the past decade

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: