Nomadland, Banksy, and the Antiwork Movement

Labor, Like Capital, Is Borderless in a Digital Economy

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Nomadland, Banksy, and Our Web3 Future of Work

About 30 minutes into Nomadland—last year’s Best Picture winner—there’s a scene that takes place around a campfire. Nomads (played in the film not by actors, but by real-life nomads) tell the stories of how they came to be nomads.

One woman shares how she grew disillusioned with her “normal” life:

“I worked in corporate America for 20 years. My friend Bill worked at the same company as me. Bill had liver failure a week before he was due to retire. HR called him to plan his retirement, and he died 10 days later. He died never having been able to take that sailboat he bought out of his driveway—he missed out on everything. And he told me before he died, ‘Just don’t waste any time, girl. Don’t waste any time.’ So I became a nomad. I didn’t want my sailboat to be in the driveway when I died.”

Nomadland is a portrait of people who have been chewed up and spat out by corporate America. Its protagonist is Fern (Frances McDormand), a woman who loses her job when the construction plant in her Nevada town shuts down during the Great Recession.

Fern lives in her van and subsists on the odd job—during the holiday shopping rush, for instance, she takes a job at an Amazon distribution center. (The scenes from the movie were filmed at a real Amazon facility after McDormand emailed Amazon and “asked nicely”.)

Nomadland captures the slow decay of the American dream. Watching the film helps you understand modern America: it helps you make sense of support for Donald Trump on the right and support for Bernie Sanders on the left; it helps you understand the rise of Occupy Wall Street in 2011 and the rise of WallStreetBets in 2021. Watching Nomadland contextualizes the world that Gen Z grew up in.

Over the weekend, I went to a Banksy exhibit in LA. I was struck by how much Banksy’s work—much of it 20 years old—embodies Gen Z’s worldview. His work is anti-capitalist, anti-consumerist, anti-institution. It decries a broken system.

One of my favorite Banksy pieces is “Barcode”:

“Barcode” reminds me of Gen Z’s growing antipathy to Amazon and Jeff Bezos. We saw flashes of this hostility in 2019, when condemnation from AOC and others led Amazon to cancel its HQ2 plans in New York. And more recently, we saw vitriol aimed at Bezos when he became the richest man in the world, when he retired, and when he went to space. Scrolling TikTok, you’re hard pressed to find a positive comment about Bezos.

Banksy’s “Sale Ends” captures a similar anti-consumerism attitude:

It’s well-known by now that Millennials are the first American generation to be worse off than their parents. Despite being better educated than Boomers, Millennials earn ~20% less. Even before COVID, 15% of Millennials were living in their parents’ home—double the share of Boomers and Silents who lived at home at the same age. Homeownership rates, across every income and education level, are lower for Millennials than for every previous generation.

And when young workers were still reeling from the Great Recession, COVID hit. A report from Data for Progress found that 52% of people under 45 lost a job, were put on leave, or had hours reduced due to the pandemic, compared to 26% of people over the age of 45. The lifestyle millions of young people were promised—the house, car, white-picket fence, 2.4 kids—inched even further beyond their reach.

Or in Banksy’s words: “Sorry! The lifestyle you ordered is currently out of stock.”

But where Millennials were idealistic, Gen Zs are pragmatic. Much of Banksy’s worldview, like Gen Z’s, is borderline nihilistic:

This is a key difference between Millennials and Gen Zs. A recent Dazed article examined why Gen Zs reject Millennials’ work-focused mindsets and pop culture.

Having entered the work market in the midst of an economic crisis, much of what is now considered ‘Millennial culture’ celebrates a capitalistic, work-focused mindset. It’s all about ‘side hustles’, having a ‘five-year plan’, ‘making your job your LIFE’, and aspiring to be ‘a boss’. To Gen Z, the Millennial attitude towards work has provided much opportunity for mockery. In fact, it’s a key part of the so-called “beef” between the two generations, which started with TikTok videos mocking Millennials for supposedly being overly corporate, among other things. Gen Z are more likely to have the mindset that work is simply labour, rather than a person’s entire identity. So the idea of dreaming to be a cog in a big corporate machine, or working in a job you hate because it’s in the ‘five year plan’, probably seems less aspirational—as does a monologue like the ‘cerulean speech’.

To Gen Zs, Leslie Knope’s sunny optimism is impractical, and Anne Hathaway’s character in The Devil Wears Prada isn’t admirable, but pathetic.

This sets the stage for the revolution happening in work.

Part of this revolution is a disaggregation of work, as young people reject “traditional” career paths in lieu of more autonomous and flexible opportunities. We see this in the gig economy (Uber, DoorDash, Instacart) and in the creator economy (Roblox, TikTok, YouTube). By 2027, America’s workforce will be majority-freelance.

A new infrastructure is being built for this new economy by companies like Found, Creative Juice, and Collective.

Part of the rise in self-employment, of course, isn’t voluntary—it’s a symptom of the Great Recession, the pandemic, and growing inequality. But part of it is intentional, a massive shift to embracing autonomy and flexibility.

Where prior generations rented time to a corporation, this new generation “manifests” their own fortunes with equity upside. A celebrity of yesteryear might appear in a Gatorade commercial; earlier this month, the YouTubers Logan Paul and KSI leveraged their massive distribution to launch their own Gatorade competitor. Times are changing.

In 1822, an employee in one of the world’s first office buildings bemoaned his new reality. In a letter to a friend, he wrote: “You don’t know how wearisome it is to breathe the air of four pent walls, without relief, day after day, all the golden hours of the day between ten and four.” He wished for “a few years between the grave and the desk” and then concluded, “but alas, they are the same.” While letters seem to have unfortunately grown less dramatic over the ensuing 200 years, the office-centric culture of work hasn’t changed. (The most popular show of the last 20 years is literally called The Office.)

People are now beginning to take a hard look at that reality. They’re asking questions—should we really spend 40+ hours a week tethered to our desks, away from loved ones, commuting in traffic twice a day?

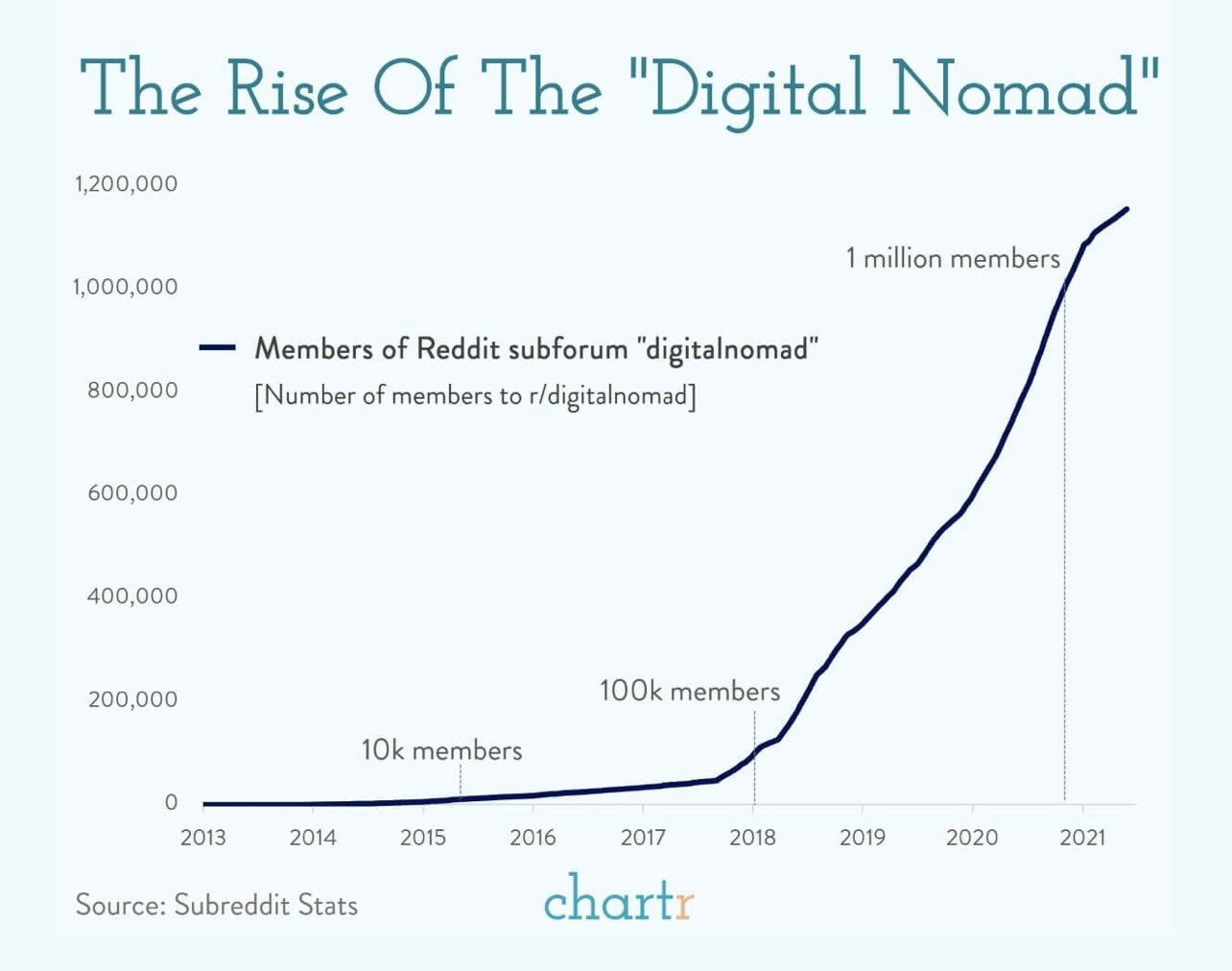

We’re seeing a massive rise in “digital nomads” who move freely between locations and who work on the internet.

While part of the revolution of work is more self-directed, remote, or online work, part of the revolution is more existential.

One of the best pieces I’ve read in recent months is Anna Codrea-Rado’s long Vice piece called Inside the Online Movement to End Work. The journalist goes deep into r/antiwork, which has become one of Reddit’s most popular subreddits. The antiwork subreddit describes itself as “a subreddit for those who want to end work, are curious about ending work, and want to get the most out of a work-free life.” r/antiwork now has 1.7 million members (who fittingly call themselves “Idlers”), up from just 13,000 in 2019. Comically, the subreddit has over twice as many members as r/careerguidance.

Idlers share ethos with the nomads in Nomadland. It’s not that they can’t find work—they fully reject the premise of working in our modern capitalist society. They want to rethink what work (and life) should be.

Interestingly, our modern concept of work is relatively new—only about 300 years old. For most of human history—from the Greeks, to the Romans, to the Middle Ages—leisure was the basis of culture. Only in the 16th century, when the Reformation brought the rise of the Protestant work ethic, did people begin to see work as a way to bring oneself closer to God. The religious aspect of work faded, but faith in hard work persisted, evolving into the modern-day spirit of capitalism.

We seem to be on the precipice of a rethinking of work and capitalism, with roots both cultural (Gen Z) and technological (Web3).

Play-to-earn gaming—most notably Axie Infinity—rose to prominence in 2021 as a way to make money while gaming. Play-to-earn flipped normal conceptions of work on its head. Earning a living making TikToks is a similarly novel concept. What’s unique about Web3 is that it makes new behaviors lucrative and economically-viable.

Back in 2005, economists wrote that modders—people who modify video games—are a form of “unpaid labor”:

Modders, however, are rarely remunerated for taking the risks the industry itself shuns. While successful modders, such as Counter-Strike’s creator, Minh Le, enjoy a celebrity status that enables them to find employment in the games industry, many modders are either uninterested or unable to translate the social capital gained through modding into gainful employment. The precarious status of modding as a form of unpaid labour is veiled by the perception of modding as a leisure activity, or simply as an extension of play. This draws attention to the fact that in the entertainment industries, the relationship between work and play is changing, leading, as it were, to a hybrid form of “playbour”.

Web3 changes the calculus (as do Web2 business model innovations like Roblox).

You can extend this concept even further. What if today’s wealth creation was distributed differently? Instead of Facebook making money from you browsing social media, maybe advertisers could pay you in return for your attention. What if play-to-earn became browse-to-earn?

About a year ago, I shared the framework that I use to think through the nebulous VC-buzzword term “future of work”:

First comes job readiness—you have to prepare for a job. Then comes job discovery—finding a job. And finally, you have job success—tools to make you better at your job.

All three of these stages can be extended into a digital economy built on the rails of Web3. For the education component, you have learning DAOs like Nick deWilde’s Invisible College and Peter Yang’s Odyssey. You have companies like Rabbithole that incentivize people to get into Web3 by paying them to…well, go down the rabbit hole.

For job discovery, we’ll see “labor marketplaces” to discover DAOs you can contribute to.

The author of this tweet—in a piece called I’m Quitting Web2 (And You Should To)—declared: “Over the next year(s), I'll likely transform from a career professional into a pseudonymous agent across a variety of projects.” DAO operating systems like Utopia Labs will make it easy for DAOs to manage thousands or millions of contributors.

And for job success, new Web3 products broaden how a person can work and earn income. Royal, for instance, is a tool for music artists to transform their economics with NFTs. This week, Royal is dropping two Nas songs as NFTs. NFT holders get access to Gold, Platinum, or Diamond tiers, each with its own level of access to Nas.

A member of r/antiwork named Penny says, “There are two sides to the antiwork community. Some people are saying, ‘We shouldn’t have to work at all’ and other people are saying that work just should be better.” The first side is a cultural reckoning—and, I’d wager, comprises a smaller group of people. The second side, making work better, is where innovation will happen, much of it stemming from Web3.

We’re all becoming workers in the digital economy. In our analog economy, capital was fluid, flowing across borders and enriching the investing class. The labor class, meanwhile, was rigid and left behind. In our digital economy, labor, like capital, finally becomes borderless.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Millennials Are the New Lost Generation | Annie Lowrey

Inside the Online Movement to End Work | Anna Codrea-Rado

Game Studios Are Turning Play Into Work | Will Bedingfield

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: