The Evolution of the Influencer

Entering the Influencer 2.0 Era

This is a weekly newsletter about tech, media, and culture. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, you can subscribe here:

The Evolution of the Influencer

In January 2018, I posted a sponsored Instagram video for Calm. I had around 275,000 followers at the time, and I encouraged my followers to begin the New Year with meditation and mindfulness as part of Calm’s #YearofCalm campaign.

In January 2019—a year later—my firm, TPG Growth, led Calm’s Series B round. And a year after that, in January 2020, I was working at Calm and scaling the influencer marketing channel.

I’ve been deeply interested in the influencer movement for the better part of a decade—as an influencer, as an investor, and as an operator. And I’m fascinated by how the meaning of “influencer” continues to evolve, spawning a full-fledged new economy.

One note before digging in: while the term “creator” has gained popularity, I’ll use “influencer” here. I view “influencer” as a broader catch-all term and will offer a rough definition: An influencer is someone who moves culture and changes consumer behavior by sharing content on the Internet.

There are three broad trends driving the future of influencers:

Everyone is now able to be an influencer,

Influencers have more direct, authentic connections to their communities, and

Influencers have new tools to formalize and monetize their work.

I’ll dig into each of these trends and some startups building on them. Then I’ll end by looking at how OnlyFans captures the convergence of these three trends.

1️⃣ Everyone Is An Influencer

In his 2011 letter to Amazon shareholders, Jeff Bezos wrote:

Even well-meaning gatekeepers slow innovation. When a platform is self-service, even the improbable ideas can get tried, because there’s no expert gatekeeper ready to say “that will never work!” And guess what—many of those improbable ideas do work, and society is the beneficiary of that diversity.

Bezos was writing about Amazon’s push into publishing, but his words hold true for the emergence of influencers. Before the Internet, celebrities were created by media gatekeepers: faceless executives in far-flung skyscrapers in Los Angeles or New York, making subjective decisions about who could and should become famous. Internet platforms level the playing field; they let the market itself allocate fame and influence.

Earlier this year, I wrote about how TikTok’s algorithmic feed levels the playing field for discovery. According to one TikTok executive, every single TikTok video is given 100 views. How the video performs in those 100 views—how many people like it, comment on it, share it—determines how many more people will see the video in their feed, and so on. Anyone can go viral if their content is good enough. Fame is completely democratized.

Take Charli D’Amelio. A year ago, D’Amelio was an unknown Connecticut teenager who downloaded an app called TikTok. In 12 months, she’s gained 87 million followers, made $4 million, signed with a top Hollywood agency, and become the new face of Hollister. 🤯 We’re all out here just trying to make it through 2020, and D’Amelio is absolutely thriving.

Or take Sarah Cooper. She rose to fame this past spring for her (hilarious) Trump impersonations on TikTok. Now, she has a Netflix deal, a TV show on CBS, and recently spoke at the Democratic National Convention. Both D’Amelio and Cooper used the Internet to circumvent conventional paths to fame.

The classic 1950 movie Sunset Boulevard tells the story of a once-famous silent film actress, Norma Desmond. When silent films are replaced by the “talkies”, Norma Desmond is quickly forgotten by Hollywood.

Here’s an idea for a modern remake of Sunset Boulevard: a “traditional” movie star—the embodiment of fame for the last century—is displaced by a young TikTok or YouTube star. (If you’re a film agent reading this, hit me up!)

Just as silent film stars like Norma Desmond were replaced by movie stars like Grace Kelly and Bette Davis a century ago, today’s movie stars (your Angelina Jolies and Jennifer Lawrences) are being replaced by Internet stars. The Internet obfuscates the gatekeepers of fame; anyone can be influential.

This trend creates an economic opportunity for companies. The influencer marketing industry will be worth $15 billion by 2022, up from $8 billion in 2019, and that growth is powered by the long tail of influencers.

A general truth on Internet platforms is that smaller audience sizes have higher engagement rates. In other words, someone with 1,000,000 followers might average 1% engagement (likes + comments) on their posts. Someone with 100,000 followers, meanwhile, might average 5% engagement.

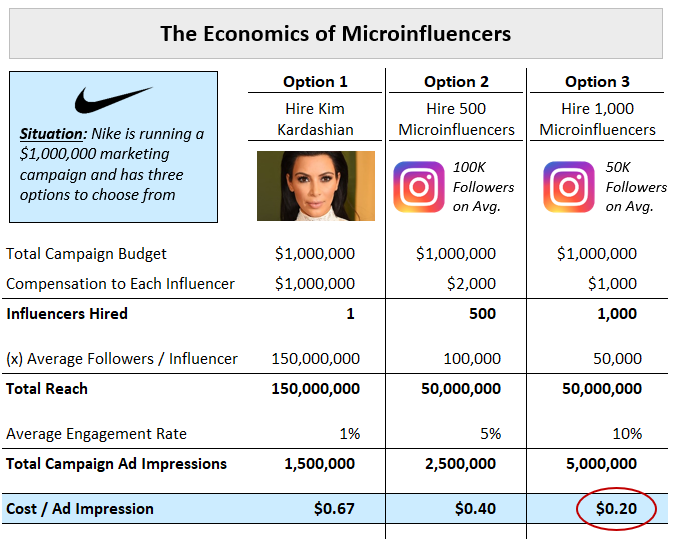

This means that “microinfluencers”—people with ~10K to ~100K followers—have better economics for brands:

In the example above, Nike could spend its entire $1,000,000 budget to hire Kim Kardashian, who has a ~1% engagement rate on her posts. Or it could hire 1,000 microinfluencers, each with 50K followers, and receive more impressions per dollar spent.

Companies like Glossier and FabFitFun have built huge businesses by leveraging microinfluencers and user-generated content. In an interview with Kara Swisher, Glossier’s Emily Weiss said, “Every single person is an influencer.”

Three startups building on the idea that everyone is an influencer are Supergreat, Zyper, and Dia&Co:

Supergreat: Beauty influencers on YouTube were the original Internet influencers. Major influencers went on to launch their own beauty brands: Kylie Jenner (Kylie Cosmetics), Huda Kattan (Huda Beauty), Michelle Phan (ipsy), Jeffree Star (Jeffree Star Cosmetics), Lady Gaga (Haus Beauty), Rihanna (Fenty), Selena Gomez (Rare Beauty). Supergreat is the broadening of this trend, letting anyone recommend beauty products. In the founders’ words, “We don’t expect our users to have massive followings.” Supergreat users earn supercoins for creating reviews or referring friends, then use those supercoins to take part in product drops on the app.

Zyper: Zyper helps brands connect to its most enthusiastic customers, who can then create user-generated content for the brand to share.

Dia&Co: In a recent podcast interview, USV’s Rebecca Kaden explained Dia&Co’s unique customer acquisition engine. When a customer receives her Dia products, she tries them on at home and posts on Facebook. “Should I keep this one? What about this one?” Dia’s customers are natural evangelists, generating organic growth through word-of-mouth. Every Dia customer—no matter the size of her following—is an influencer for the brand.

Just taking a quick breather to remind you to subscribe if you haven’t already!

2️⃣ Direct, Authentic Connections

My (short-lived) stint as an influencer came at what I like to call “peak Instagram”. Picture colorful murals, latte art, and the Museum of Ice Cream. Influencers in this era—which I’ll call the Influencer 1.0 era—were perfectly coiffed, filtered, and edited. But rapidly, led by Gen Z, influencers have become more accessible and relatable.

Compare the below Instagram posts from Beyoncé. The image on the left could have been in a magazine. It’s professional, yet impersonal; it lacks intimacy and authenticity. The image on the right, meanwhile, is deeply personal and offers a window into Beyoncé’s life. The image on the right has 5 times as many likes and 18 times as many comments.

The Internet enabled unprecedented access to celebrities, and the celebrities who have done best on social media are those who have leaned into this access. Influence is no longer about being an elusive star on the red carpet; influence is about being intimately familiar and relatable.

Younger social media users understand this innately. This is one reason I’m bearish on companies like Brud, which are creating virtual influencers (yes, it’s a thing). Gen Z has a strong “authenticity detector” and I’m skeptical that digitally-created influencers will replace real, tangible, relatable people.

The trend toward Internet-driven authenticity cuts across industries. Take Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. AOC isn’t a traditional social media influencer, but her political success was born from her social media savvy. AOC grew up with the Internet and understands how to forge direct, personal connections with her followers. Her command over digital distribution channels—her fluency in social media—gives her an edge over older politicians still rooted in 20th-century media. AOC’s playbook foreshadows the next generation of politics.

Three startups building companies around direct, authentic connections are Community, Cameo, and Superpeer:

Community: Community gives celebrities a phone number, and then the celebrities share their number with fans. This direct access to fans helps celebrities monetize in new ways: selling concert tickets, promoting music videos, selling merchandise. Everyone from J Lo to Amy Schumer to Paul McCartney uses Community.

Community also has a unique organic growth engine. Community only needs to attract one side of its “marketplace”—the celebrities—who are already incentivized to use the product because it helps them monetize fans. Celebrities then use their massive social reach to get tens of thousands of fans to sign up. This allows Community to spend almost nothing on user acquisition.

Cameo: By letting you buy a personal video from a celebrity, Cameo gives you a new level of access. There are over 30,000 celebrities on the app, ranging from Snoop Dogg ($800) to Lindsay Lohan ($310) to 94-year-old Dick van Dyke ($1,000).

Superpeer: Superpeer is like Cameo, but connects influencers and fans for 1-on-1 live video chats. Influencers set their price and availability, then chat with fans or answer questions. It’s easy to picture Superpeer resonating in niches: beauty influencers giving skincare tips; moms and dads answering questions about parenting; food influencers helping their fans learn to cook.

3️⃣ New Tools to Monetize

If the Influencer 1.0 era was about sponsored posts, the Influencer 2.0 era is about giving influencers new ways to make money:

The Internet made it possible for an influencer to turn herself into a business. From Gwyneth Paltrow (Goop) to Jessica Alba (Honest Company) to Ryan Reynolds (Aviation Gin), major celebrities launched their own brands. This was a breakthrough: in a previous world, Rihanna would be stuck partnering with Estée Lauder instead of creating Fenty. Companies like Shopify, Stripe, and Instagram made this possible.

But company creation was only accessible to mega-influencers. And why should you have to be Kylie Jenner to launch your own brand? In the Influencer 2.0 era, anyone will be able to launch a brand.

In China, there’s a company called Ruhnn that acts as an incubator and accelerator for influencers. Ruhnn identifies promising up-and-coming influencers, then helps them launch digitally-native brands. Ruhnn's top influencer, Zhang Dayi, has 15 million followers on Weibo and last year did $90M in sales by herself. Ruhnn is essentially a “business-in-a-box” platform for influencers.

Direct-to-consumer brands have struggled because of increasing customer acquisition costs on Google and Facebook. Influencer brands circumvent this problem: influencers simply use their social channels to drive organic customer acquisition. This is how Kylie Cosmetics hit $300M in first-year revenue with $0 marketing spend. (The downside: the brand is entirely reliant on one person. When Kylie Jenner took a social media break during her pregnancy, sales immediately dropped 50%.)

The most compelling companies are the tools and platforms enabling this—the picks and shovels—that are diversified across influencers. In addition to the Shopifys and Stripes, startups will emerge to provide manufacturing, fulfillment, and other services for the influencer economy.

Influencers are still doing sponsored posts in the 2.0 era, but the posts look different. In line with the “Direct, Authentic Connection” trend, sponsored posts are less contrived. Take David Dobrik, an influencer on YouTube (18.3M subscribers) and TikTok (22.4M followers):

Dobrik has a long-standing collaboration with SeatGeek and has actually made his SeatGeek representative, Ian, a recurring character in his YouTube videos. He often calls Ian in his videos and asks for more money:

Dobrik isn’t sheepish about sponsored content; he owns it and even uses it to enhance his comedy.

Monetization tools and platforms for influencers can be vertical or horizontal:

Vertical tools and platforms help influencers monetize in one way: writing with Substack, podcasting with Glow, personalized videos with Cameo, etc.

Horizontal tools and platforms cut across mediums. Stir, for example, provides a suite of tools for managing an influencer’s broader business. Karat extends influencers credit based on stats like followers. Patreon was a pioneer here and just raised a Series E at a $1 billion valuation.

(Patreon was created to solve the monetization problems of the Influencer 1.0 era. Founder Jack Conte was a musician on YouTube. In one 28-day period, during which his account generated 1,062,569 views, he received a measly $166.10 payout. He realized there needed to be a better way to earn a living on the Internet and built the subscription-based Patreon.)

Jemi is also a horizontal tool powering creator monetization. Using Jemi, creators can monetize their followings and their time.

Jemi is broader than Cameo, Superpeer, or Substack, letting creators collate in one all-in-one shop the various ways to interact with their community and earn income.

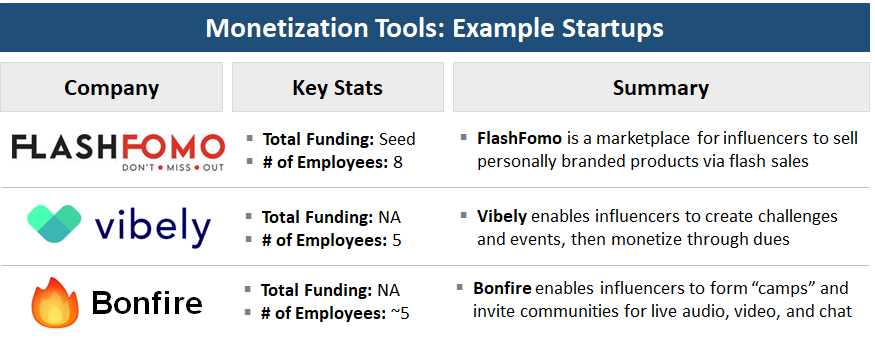

Three other startups helping influencers monetize are FlashFomo, Vibely, and Bonfire:

FlashFomo: FlashFomo is like Ruhnn, helping leading influencers create and share exclusive products. It provides influencers with an online storefront, manufacturing, and shipping.

Vibely: Vibely’s mission is to “scale authenticity” and helps influencers make money by scheduling meetups and events with fans for a small fee.

Bonfire: Bonfire is a new consumer social app that allows people to join “camps” around shared interests. An influencer is able to launch a paid camp, giving them a paywalled “room” for livestreaming with their fans. I chatted with Bonfire co-founder Hugo Pakula this week and was incredibly impressed by Bonfire’s organic growth. Bonfire’s viral coefficient is 4, meaning that every new user brings on four additional users. A camp “creator” typically brings between 30 and 200 people into the app.

OnlyFans and the Influencer 2.0 Era

It’s delicate to draw lessons from OnlyFans, because it’s a very different platform. It’s important to remember that thousands of sex workers rely on OnlyFans to earn a living—workers who have long been persecuted and exploited by their industry. OnlyFans has also become especially crucial to these workers’ livelihoods during the pandemic.

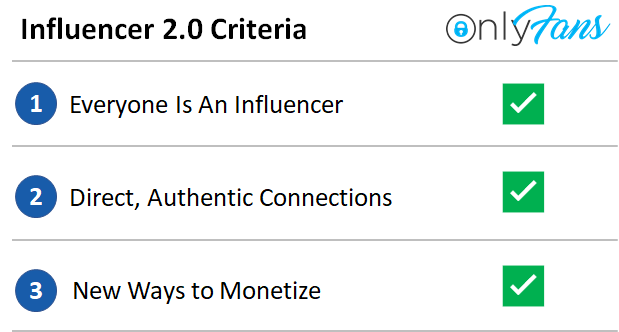

When analyzing OnlyFans, it’s important to not lose sight of that fact. But there are also lessons to be drawn from OnlyFans’ success, as the platform captures all three of the aforementioned trends.

On OnlyFans, anyone can create a paywalled account and set a subscription price—$5/month, $20/month, etc. Consumers were already asking for a paywalled platform:

On Instagram, some influencers hacked the “Close Friends” feature, which lets users post Stories visible only to a specific group of people. Influencers charged a few bucks a month for access to their Close Friends—essentially the same model that OnlyFans has formalized today.

The Influencer 1.0 era is waning. (It’s fitting that Keeping Up With the Kardashians—the embodiment of Influencer 1.0—just announced that it’s ending the show.) The Influencer 2.0 era is emerging in its place.

OnlyFans is fascinating because it has all the hallmarks of an Influencer 2.0 platform:

I’m not sure OnlyFans will move beyond adult content, but it’s been incredibly successful at disrupting the pornography industry.

Lines blur between the three trends above; many Influencer 2.0 companies touch on more than one. Startups like Cameo and Superpeer, for example, both create direct connections and give influencers new ways to earn income. Startups like Supergreat enable anyone to be an influencer, which in turn reinforces intimacy and authenticity.

Influencer 2.0 also cuts across many of the trends and sectors I write about in this newsletter:

The Future of Work: In 2020, millions of influencers earn a living on social platforms like Instagram, YouTube, Twitch, and TikTok. These influencers are the foundation of the “solopreneur” phenomenon, which is disaggregating work and changing the meaning of a career.

Consumer Social & Next-Gen Media: Content platforms are the foundation of the influencer movement. They determine how people create and interact (a recent example: the emergence of TikTok).

Commerce: Influencers are the future of discovery-driven, brand-centric commerce. This means that they’re juxtaposed to Amazon and search-driven, brand-agnostic commerce. Picks and shovels like Shopify and Stripe enable influencer commerce.

Most of all, the Influencer 2.0 era captures what the Internet does best: it removes gatekeepers, broadens access, and creates opportunity.

Sources & Additional Reading

Check these out for further reading on this subject:

Blake Robbins, Turner Novak, Taylor Lorenz, & Julie Young are some of my favorite writers on Internet culture and consumer social. If you enjoyed this piece, I highly recommend checking out their writing.

Some other good reads: A deep-dive on Brud and Lil Miquela, a window into how Gen Z uses TikTok, and why the “Instagram aesthetic” is dying

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox weekly: