Reality Privilege and Living Your Life Online

This is a weekly newsletter about how culture and technology intersect. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Reality Privilege and Living Your Life Online

There’s a trend on TikTok where people overlay Alicia Keys’ soaring vocals from “Empire State of Mind” onto stunning footage of New York’s skyline. As you watch skyscrapers glimmer, you hear the lyrics: “Baby I’m from Newwwwwww Yorkkkkkkkkkk, concrete jungle where dreamsssss are madeeeee of.” It’s hard to watch these videos and not fall in love with New York.

Because this is TikTok, people immediately began to parody these videos. It became popular to sing your own lyrics to the song based on where you live. One young woman sings off-key, “Baby I’m from New Mexicooooo” and includes footage of her town’s empty strip mall and parking lot.

These videos are undeniably funny, but they’re also sad. Maybe the creators are happier living where they are; maybe they have no desire to live in New York. But reading through the comments reminds you how unequal the world is:

“It’s my dream to live in New York.”

“I want to go to New York more than anything.”

“I’ve never been on a plane but when I can finally afford a ticket I want to visit NYC.”

Less than half of Americans (48%) fly on a plane each year. About 4 in 10 Americans have never left the country—and 63% of those people say that an international trip is unaffordable. These statistics are for America, the wealthiest nation on Earth.

Around the world, millions of people would rather live somewhere else, and most will never have that chance. Watching these TikTok videos—watching people’s self-deprecating admissions of their own less-than-exciting environments—reminds me of the concept of “Reality Privilege.”

In a recent interview, Marc Andreessen broke down Reality Privilege:

Your question is a great example of what I call Reality Privilege. This is a paraphrase of a concept articulated by Beau Cronin: “Consider the possibility that a visceral defense of the physical, and an accompanying dismissal of the virtual as inferior or escapist, is a result of superuser privileges.” A small percent of people live in a real-world environment that is rich, even overflowing, with glorious substance, beautiful settings, plentiful stimulation, and many fascinating people to talk to, and to work with, and to date. These are also *all* of the people who get to ask probing questions like yours. Everyone else, the vast majority of humanity, lacks Reality Privilege—their online world is, or will be, immeasurably richer and more fulfilling than most of the physical and social environment around them in the quote-unquote real world.

The Reality Privileged, of course, call this conclusion dystopian, and demand that we prioritize improvements in reality over improvements in virtuality. To which I say: reality has had 5,000 years to get good, and is clearly still woefully lacking for most people; I don't think we should wait another 5,000 years to see if it eventually closes the gap. We should build—and we are building—online worlds that make life and work and love wonderful for everyone, no matter what level of reality deprivation they find themselves in.

Here’s a thought experiment for the counterfactual. Suppose we had all just spent the last 15 months of COVID lockdowns *without* the Internet, without the virtual world. As bad as the lockdowns have been for people’s well-being—and they've been bad—how much worse would they have been without the Internet? I think the answer is clear: profoundly, terribly worse. (Of course, pandemic lockdowns are not the norm—for that, we’ll have to wait for the climate lockdowns.)

It’s easy to read about futuristic tech concepts like the metaverse (often in this newsletter) and to wring your hands. Our online lives are still relatively new; even 10 years ago, only 1 in 3 Americans owned a smartphone. Virtual worlds, immersive online experiences, digital economies—these concepts are new and different and often uncomfortable. Though I’m a devoted tech optimistic, even I occasionally find it all a little dystopian.

But the concept of Reality Privilege resonates. Not everyone has the chance to live in Manhattan. Not everyone is able to visit the Pyramids, the Taj Mahal, Machu Picchu. As our online lives become richer and more vibrant—and as technology improves—digital experiences will at least come close to capturing (and, in some cases, will likely surpass) those offline experiences.

When I think of forging the metaverse and dissolving Reality Privilege, I think of three broad building blocks:

Virtual Reality & Augmented Reality,

Gaming, and

Crypto

Let’s look at the role each of them plays.

Virtual Reality & Augmented Reality

Next month, the first LGBTQ+ virtual reality museum will open. The museum is the brainchild of Antonia Forster, a Unity developer who wanted to create a space where queer stories can be told in more immersive, expressive, and personal ways.

The LGBTQ+ VR Museum will showcase three-dimensional digital objects that were formative to a queer person’s personal coming out journey. Each object is accompanied by an audio recording explaining the object’s meaning.

Forster captures what’s so transformative about new technologies:

I think, in some ways, tech democratizes the ability to tell stories.

I think one of the very best things that technology can do is not only give everyone the ability to platform the stories that they feel are important, but also to unlock new ways to tell those stories. VR and AR give creators the unique ability to put you in someone’s shoes, as it were, and walk you through their story.

New technologies are fundamentally about new ways of experiencing the world. And VR and AR will be the most immersive technologies yet, allowing you to deeply and powerfully experience a feeling or story or place. This is why VR and AR are central to breaking down Reality Privilege.

Consider other innovations in VR / AR:

“Notes on Blindness” explores a man’s sensory and psychological experience of losing his vision.

“Traveling While Black” is an immersive experience of racism in America, covering decades of black American experiences before and during Civil Rights.

“We Live Here” follows a homeless woman living in a tent city in Los Angeles from her perspective.

VR and AR transport you. Applications go far beyond entertainment. Imagine diversity and inclusion training where you can experience being in another person’s shoes. Imagine your child learning about the solar system by traveling through outer space. Imagine your doctor explaining your upcoming surgery by showing you what’s going on inside your body.

Because of Reality Privilege, virtual reality will be more revolutionary than augmented reality. In ways that AR can’t, VR will bring you to new worlds—you can experience Manhattan like a local. You can quickly and cheaply “visit” the Pyramids, the Taj Majal, Machu Picchu. For the first time, millions of people will be able to experience things previously limited to a lucky few.

Gaming

Over the last decade, the lines between gaming (in its traditional definition) and social media have blurred. Instead of achieving an objective or “winning” a game, millions turn to gaming as a social outlet. People socialize and attend concerts in Fortnite’s Party Royale. Grand Theft Auto has a casino exclusively for hanging out—it serves no purpose in the game. Kids throw birthday parties on Roblox.

On May 14th, Roblox removed the word “game” from across its platform, replacing it with “experience.” This was primarily due to the ongoing Epic Games vs. Apple court case, which likely scared Roblox, but it also suggests the company’s long-term shift. In a Roblox representative’s words: “The term ‘experiences’ is consistent with how we’ve evolved our terminology to reflect our realization of the metaverse.”

Gaming worlds are the new social networks, and this fact is central to the realization of the metaverse vision. There are 3 billion gamers on Earth. Millions (maybe billions) of people who lack Reality Privilege already turn to the richness and vibrancy of virtual worlds.

What’s critical about gaming is that it’s the gateway through which many will enter the metaverse. What starts as Grand Theft Auto the game becomes a place to socialize, which in turn becomes an immersive and robust online world like NoPixel. Already, “gaming” has become a loosely-defined term. The line where “gaming” ends and “digital life” begins will continue to blur, before disappearing altogether.

Crypto

In 1964, the media theorist Marshall McLuhan famously wrote “the medium is the message”, arguing that the technologies through which we absorb the world influence how we connect and perceive with other people and ideas.

Today, those mediums are Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube. They control our online lives. McLuhan was prescient in warning against such concentrated power:

Once we have surrendered our senses and nervous systems to the private manipulation of those who would try to benefit from taking a lease on our eyes and ears and nerves, we don’t really have any rights left. Leasing our eyes and ears and nerves to commercial interests is like handing over the common speech to a private corporation, or like giving the earth’s atmosphere to a company as a monopoly.

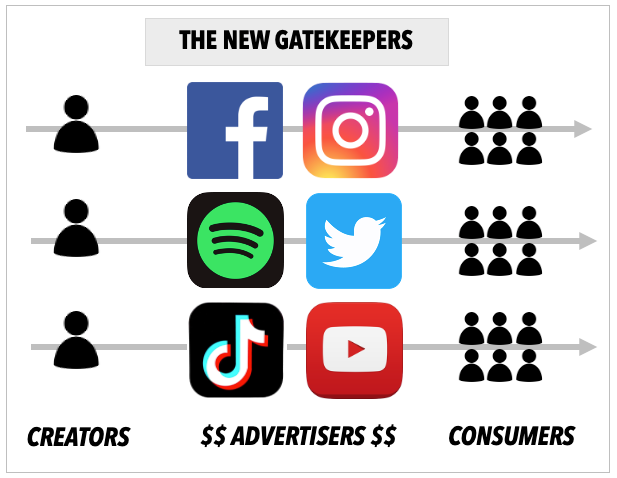

“Leasing our eyes and ears and nerves” sounds a lot like invasive digital advertising. While internet platforms disrupted the legacy gatekeepers of culture (record labels, film producers, publishers), they became the new gatekeepers. They’re built for advertisers, not for users.

The metaverse will be even more life-changing than any of these platforms. Epic Games’ Tim Sweeney warns against centralization:

This metaverse is going to be far more pervasive and powerful than anything else. If one central company gains control of this, they will become more powerful than any government and be a god on Earth.

When I think of Sweeney’s warning, I think of the OASIS in Ready Player One. The OASIS is a vast universe of immersive worlds—it’s mankind’s playground. In the protagonist’s words:

The OASIS is a place where the limits of reality are your own imagination. You can do anything, go anywhere. Like the Vacation Planet. You can surf a 50-foot monster wave in Hawaii, you can ski down the pyramids, you can climb Mount Everest with Batman.

The premise of Ready Player One is a struggle to keep the OASIS from being owned by an evil corporation. For everyone to access robust and meaningful digital experiences—to enable the breadth of experiences needed to deconstruct Reality Privilege—the metaverse must be decentralized. It can’t be owned by any one company.

Blockchain technology will enable this vision. Virtual worlds and economies will be owned and controlled by creators and consumers. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs), DeFi, social tokens, decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs)—all are central components of this future. Piers Kicks lays out the “investable universe” of this new economy:

Everyone will be able to build and consume and own the metaverse. It’s helpful to not think of the metaverse as a company or single entity: it will resemble the next iteration of the internet more than the next iteration of Facebook or TikTok or Roblox.

Final Thoughts

We’re spending more and more of our lives online. In Chain Reactions, I wrote about how stunning the scale of the internet has become; every minute on the internet:

Netflix users stream 404,444 hours of video

Instagram users post 347,222 stories

YouTube users upload 500 hours of video

Consumers spend $1,000,000 online

LinkedIn users apply for 69,444 jobs

TikTok is installed 2,704 times

Venmo users send $239,196 worth of payments

Spotify adds 28 tracks to its music library

Amazon ships 6,659 packages

WhatsApp users send 41,666,667 messages

And 1,388,889 people make video and voice calls

Every minute. American adults spend over 11 hours interacting with digital media every day. Daily media consumption on mobile has grown 6x from 45 minutes in 2011 to 4 hours and 12 minutes in 2021.

As the line between digital and physical blurs, the metaverse emerges. The three categories above are its building blocks:

VR and AR are the enabling technologies for more immersive digital experiences.

Gaming is key to widespread behavior change—what starts in gaming spreads to broader social adoption.

And crypto is central to the ethos of virtual worlds and economies: decentralized and user-owned.

Again, many of these aspects seem dystopian. Nothing will replace the “real” world at its best; like all innovations, safeguards should be put in place. But technology will unlock incredible experiences for a broader swath of the population. Particularly for those lacking Reality Privilege, life is about to get even richer and more vibrant.

Sources & Additional Reading

How a VR Museum Will Tell LGBTQ+ Stories | Matthew Olsen

Into the Void | Piers Kicks

Every Minute on the Internet | Visual Capitalist

Related Digital Native pieces:

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox each week: