Revisiting Lifetime Value and Customer Acquisition

In This Market, Solid Unit Economics Matter More Than Ever

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Revisiting Lifetime Value and Customer Acquisition

At its simplest, business comes down to straightforward math:

A business (typically) has to spend money to get a new customer.

Then, that business will generate a certain amount of money from that customer over time.

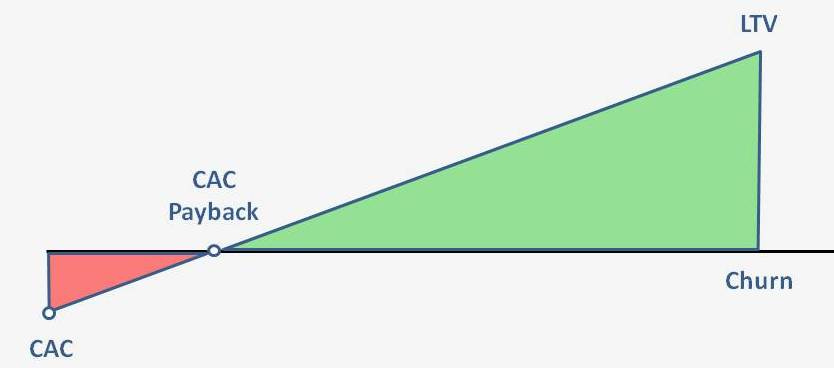

The first is referred to as Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) and the second is referred to as Customer Lifetime Value (LTV). To run a profitable and scalable business, you want LTV > CAC.

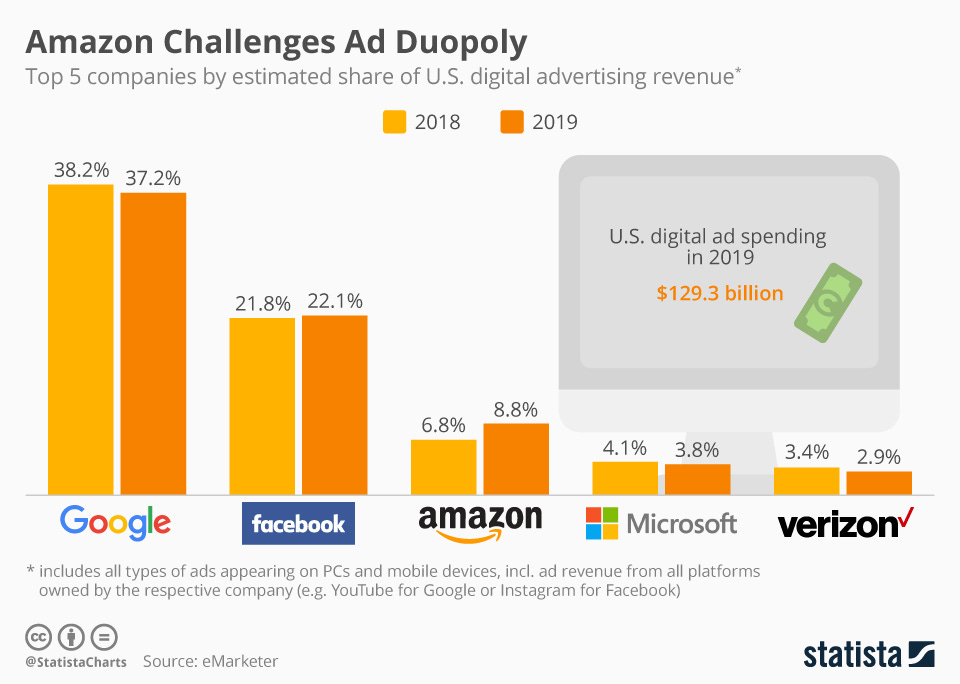

A few weeks ago, I wrote about CAC headwinds that businesses are facing in CAC: Customer Acquisition Chaos. The pressures on CAC are many. Google, Facebook, and now Amazon are monopolizing digital ad spend, and even newsfeeds and search results are finite. As Econ 101 would tell us, limited supply + growing demand = rising prices. At the same time, Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) changes have dealt a blow to digital advertising (Meta estimates a $10 billion hit to its business) and have made advertising more difficult to measure. We have rising CACs and less scalable, measurable acquisition—and it’s all happening in a recessionary market environment.

Given what’s happening with CAC, it’s worth examining LTV. Exactly 10 years ago this month, in September 2012, Bill Gurley wrote a seminal piece on LTV. In many ways, I’ll be revisiting Gurley’s piece with an eye to how the venture market has changed in the last decade. This piece will focus on LTV as it applies to consumer technology businesses, but many of the same principles can be applied more broadly.

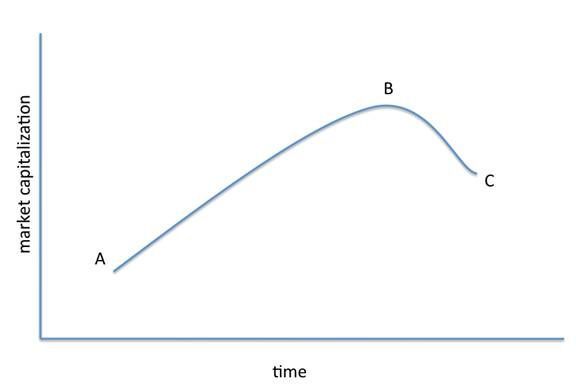

Gurley concluded his piece with a graph that would prove prescient for the 2012 to 2021 startup funding environment:

Here’s how Gurley explains it:

Let’s say a new business starts with an early market capitalization of A. Through aggressive marketing techniques, and aggressive fund raising, the company is able to achieve amazing revenue growth (and corresponding losses), but nonetheless creates a rather sizable organization. At this point, the company is valued at point B. Eventually, however, gravity ensues and the constraints outlined herein raise their head, resulting in a collapse to point C. For early founders and investors at point A, they may do OK (as long as C>A), but it will be accomplished on the backs of later stage investors that helped fund the unsustainable push to point B.

This is the story of many a startup over the past few years. Companies with poor unit economics found themselves propelled by aggressive venture dollars (which themselves were propelled by a low-interest-rate environment). Those companies then turned those dollars into aggressive customer acquisition. Until recently, the market rewarded growth at all costs. But, as Gurley says, gravity always ensues. (This year, dozens of fast-growing but unprofitable tech companies have found their stocks down 80%+; highly-profitable companies like Apple, Google, and Microsoft, meanwhile, are down only ~20% from their highs.)

The music always stops and a flawed business model always catches up to you. Ironically, the canonical example of the chart above might be Gurley’s most famous investment, Uber. Uber’s math didn’t work for many years, as the company invested aggressively in growth and found itself locked in promotion-heavy battles with rivals like Lyft in a war for market share. Today, three years post-IPO, Uber sits at a $61B market cap—well below its last private market valuation of $76B.

Thirteen years after its founding, Uber is still figuring out how to be profitable: the company’s gross margins actually declined seven percentage points over the past three years, and the net profit margin is -3%. That said, Uber is clawing its way to profitability and is expected to break into profitability in 2024. This is partly thanks to the end of the Millennial lifestyle subsidy and rising Uber prices.

The last decade showed that questionable business models can subsist for a long time (and even flourish) when capital is abundant. This isn’t to pick on Uber, nor Gurley (who is an iconic venture capitalist)—the good news for Uber is that it has a terrific product, created an enormous market, and is showing signs of positive unit economics. Other companies aren’t so fortunate.

But before going further, let’s give an example of LTV. Subscription-based business models are easy to understand, so let’s use one of those—Spotify. We’ll use dummy numbers to keep the math simple.

Spotify costs $10 a month, and let’s say the average subscriber sticks around for three years. That’s $10 x 12 x 3 = $360. That’s a lot of money!

Say it costs $60 to acquire a Spotify user. At first glance, the math looks pretty good: $360 / $60 = 6x. Not bad! A widely-held rule-of-thumb for a good LTV-to-CAC ratio is 3x, so this is looking pretty solid.

But this math commits a fatal mistake—a mistake that many companies make. It uses revenue as a proxy for LTV (*gasp*), which is a cardinal sin. Rather, LTV should take into account costs; after all, the company isn’t keeping all the money customers give it. Say Spotify has to pay out two-thirds of that $360 to record labels, and only gets to keep one-third. That $360 quickly becomes $120. There are other costs associated with running the app, with music streaming, etc. Let’s subtract another $20. Now we’re at $100 from that user, and we’re only at 1.7x LTV-to-CAC. If CAC increases to $101, we’re all of a sudden losing money on every new customer we acquire. Yikes.

Another mistake early-stage startups make is overestimating LTV. This is easy to do in the early days of a company, when you don’t know how long customers will stick around. When Spotify was two years old, how would it know that subscribers will average three years? Execs could have forecasted five years, and only later found that their unit economics fell apart. Often a better gauge in the early days is CAC payback—how quickly you’re paying back the money it costs you to get a subscriber. This chart helps visualize payback:

If Spotify banks $3 in profit per customer each month, CAC payback would be $60 / $3 = 20 months. The best consumer internet companies can pay back CAC immediately, often by incentivizing an annual subscription plan rather than a monthly plan.

For instance, here’s what Dropbox shows me when I go to “Pricing” on its website—you can see the “Billed yearly (Save up to 20%)” at the top. If I switch to the “Billed monthly” option, the price jumps to $11.99 / month, or an extra $24 per year.

Amazon Prime offers a similar annual discount: the annual plan is $99 / year, while the monthly plan will cost you $32 more. Annual plans have cash flow benefits as well, with businesses collecting that cash upfront.

One more point on LTV: it’s important to discount future years of $$ from customers. Money today is worth more than money tomorrow, and businesses are spending on CAC today for an LTV payoff tomorrow. Failing to take into account the time value of money can lead to unsustainable economics.

A rule of thumb that applies to both LTV and CAC: it’s important to segment users by organic vs. paid. Organic users are the users that discover your product naturally (e.g., word of mouth), while paid users are acquired through paid marketing channels (e.g., Instagram ads, TV commercials, and so on). On the LTV side of the equation, organic customers will always have higher LTV: an organic customer willingly chose to use your product, vs. needing to be persuaded to give it a try. An organic customer will spend more money with you, will have lower churn, and will have higher engagement. A paid customer will come in lower on each dimension, and thus have lower LTV.

The same goes for CAC. Often companies will show blended CAC, which includes both paid and organic customers. For instance, Total 2021 Marketing Spend / New Customers Added in 2021. This can give a murky view of the business. Rather, organic customers should be removed from the denominator and your math should include only paid customers. Using blended CAC is dangerous, as it can lull you into false assumptions about your marketing efficiency or overall unit economics.

Say that Spotify spent $500 million in marketing last year and added 10 million subscribers. They might calculate $500M / 10M = $50, and use that $50 CAC to plow more money into acquisition. But if a closer look reveals that 5 million of those subscribers were organic, paid CAC turns out to be $500M / 5M = $100 (the 5 million organic customers would have subscribed regardless of any paid spend!), which changes the math dramatically. All of a sudden, the entire marketing strategy might fall apart. Beware of blended CAC.

Final Thoughts

Growing rapidly with strong unit economics is very, very difficult. Often in startups, it makes sense to “land grab” in the early days (particularly in new markets) and to subsidize growth. We saw this with Uber’s and Lyft’s aggressive promotions last decade, and we’re seeing it now in BeReal’s campus ambassadors giving away free pizza or even $25 cash in exchange for proof of an app download. But land grabs only work if the underlying business model is sound. There’s no place for “voodoo math” (to borrow Gurley’s turn of phrase) when measuring LTV and CAC. Founders need to be razor sharp on intricacies like the mix of paid and organic, true profit per customer, and payback period. Because again, the music always runs out.

Of course, the holy grail for any business is organic growth. There’s no substitute for savvy, viral acquisition efforts. These are also the fun stories to tell—marketing strategies that are sexier than search engine optimization or Facebook Ads Manager. Take Zoom, which had the brilliant idea in March 2020 to come up with a “Virtual Background Competition” with real prizes; the competition led to over 100K new users.

In The Seven Heavenly Virtues of Consumer Technology this summer, I wrote about how few companies do viral marketing better than Calm. From that piece:

This savviness goes back to the very origins of the company: before starting Calm, co-founder Alex Tew created something called “The Million-Dollar Homepage.” Basically, The Million-Dollar Homepage was a website with a million pixels, each for sale for $1. The site advertised, “Own a piece of internet history!”

And it worked. The site went viral; at one point, it was in the top 200 websites in the world. Every pixel sold—mostly to advertisers eager to hoover up eyeballs flooding the site—and Alex used that $1,000,000 to launch Calm. Brilliant 🤌.

That initial viral hack got Calm off the ground, but the founders didntop there. Tongue in cheek, Calm sponsored the anxiety-ridden 2020 Presidential Election coverage on CNN. After Naomi Osaka was fined $15K for withdrawing from the French Open for her mental health, Calm offered to pay her fine and the fine of any other player who had to withdraw from a Grand Slam tournament for mental health reasons. And in my favorite example of savvy marketing, Calm put out Baa Baa Land (a riff on La La Land), an 8-hour film of sheep grazing in a field. The company marketed it as “the dullest movie ever” and promised it as the ultimate insomnia cure.

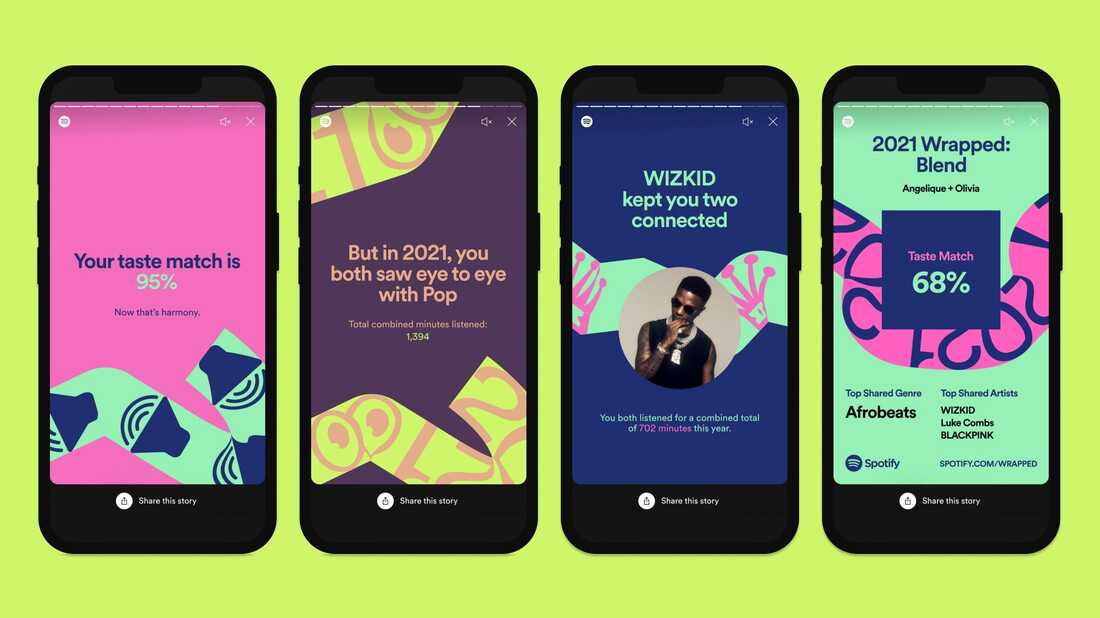

To come full circle with Spotify, take the example of Spotify Wrapped.

Every December, Spotify offers its users a retrospective on their year in music, including the songs, artists, and podcasts they listened to most. The exercise is catnip for earned media value, with millions of users advertising Spotify (for free!) by sharing their Spotify Wrapped on their Instagram Story. Brilliant.

Organic acquisition is critical, and maximizing organic’s share is key to keeping CAC down. But few businesses can get to meaningful scale on purely organic growth. And even fewer companies have the advantages of TikTok, which used Bytedance’s backing to plow over $1M per day into customer acquisition in its early days. (In 2019, TikTok was Snap’s biggest advertiser; talk about supplying weapons to the enemy.)

Most companies, rather, will need to figure out paid acquisition that’s profitable on a unit economics basis. That means intimately understanding the nuances of LTV and CAC, and how they interrelate in your business.

In this market environment, with an ongoing downturn and with skyrocketing CACs, it’s more important than ever to nail down those economics and build in discipline from the early days.

Sources & Additional Reading

Read Bill Gurley’s seminal piece on LTV, which came out 10 years ago this month: The Dangerous Seduction of the Lifetime Value Formula

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: