Speculation Nation

Kalshi, FAFOnomics, and the Financialization of Everything

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 70,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Speculation Nation: Prediction Markets and the Financialization of Everything

You know you’ve made it as a startup when South Park makes an episode about you.

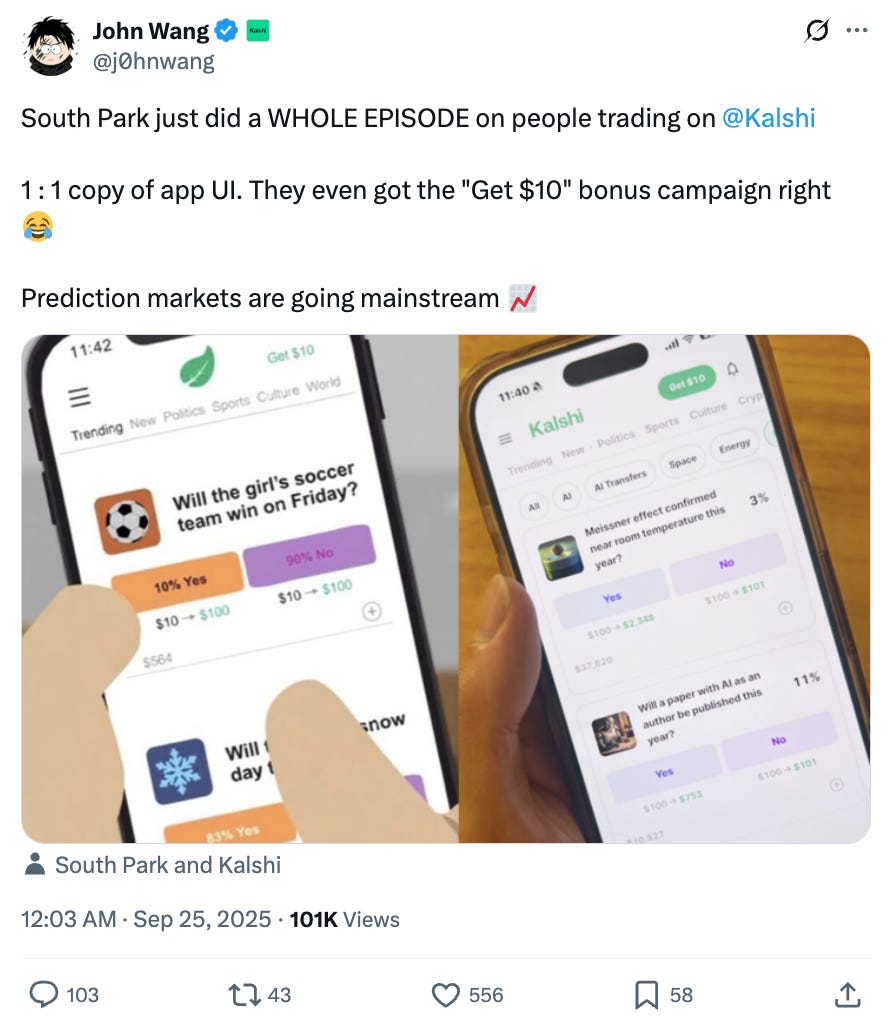

Last week’s South Park episode covered prediction markets, with the show name-checking two startups: Kalshi and Polymarket. Here’s a screenshot from the episode:

South Park did a pretty damn good job. As my friend John put it on X, the showrunners managed to make a 1-for-1 copy of the app’s interface—nice attention to detail:

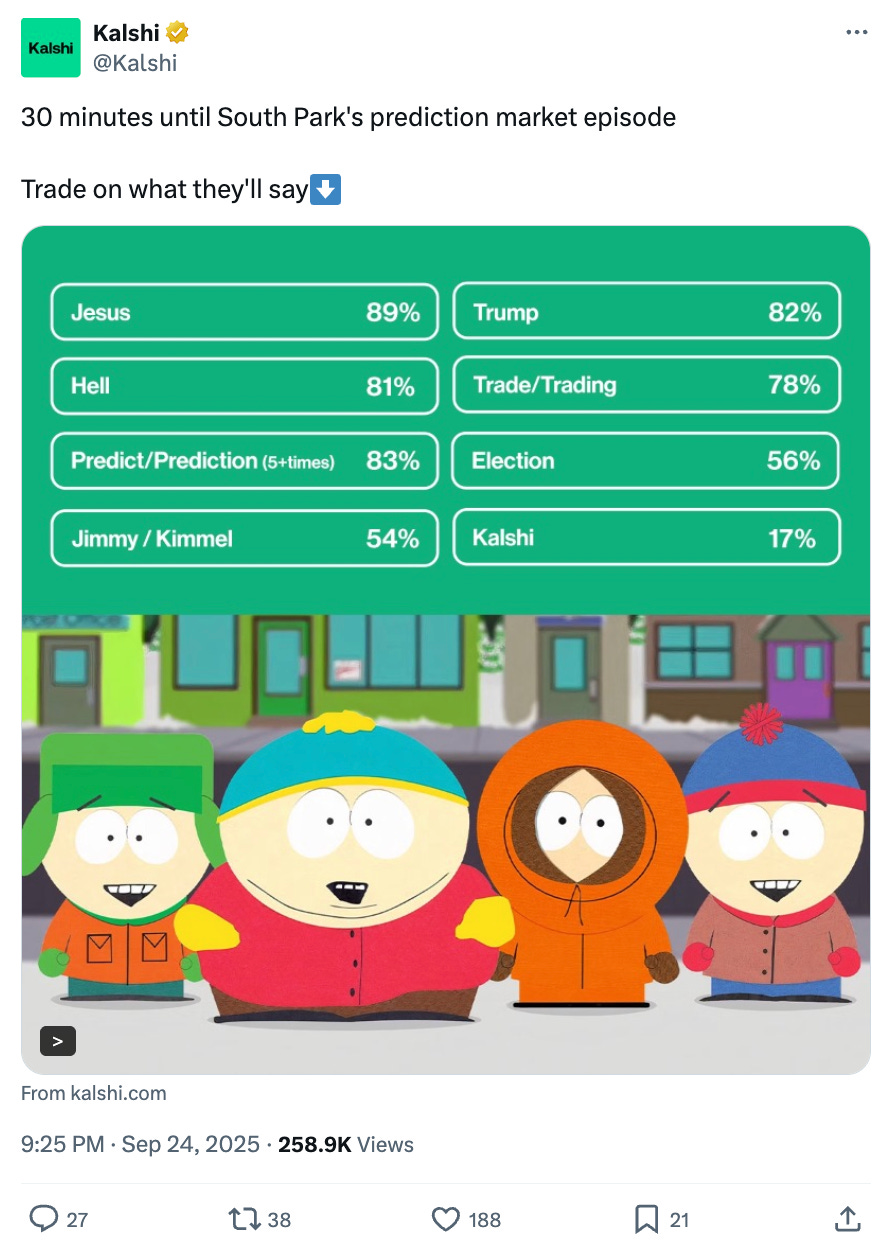

The whole thing was pretty meta: 30 minutes before the episode aired, Kalshi was asking users to trade on what South Park would mention in the episode…including if Kalshi itself would be mentioned.

Prediction markets are officially mainstream. At the end of last year, we wrote 25 Predictions for 2025. Prediction #16 was this:

Halfway into 2025, we got not one, but two unicorn prediction market companies.

On June 24th, reports surfaced that Polymarket was closing a round led by Founders Fund that would value the company at $1B. The next day, Kalshi announced a fresh round of funding led by Paradigm that valued the company at $2B.

Last fall was the first true “mainstream moment” for prediction markets, with Kalshi and Polymarket both featuring prominently in the U.S. presidential election. Each company saw a massive spike in users and trading volume (while also proving more accurate in predicting a Trump win than most pundits).

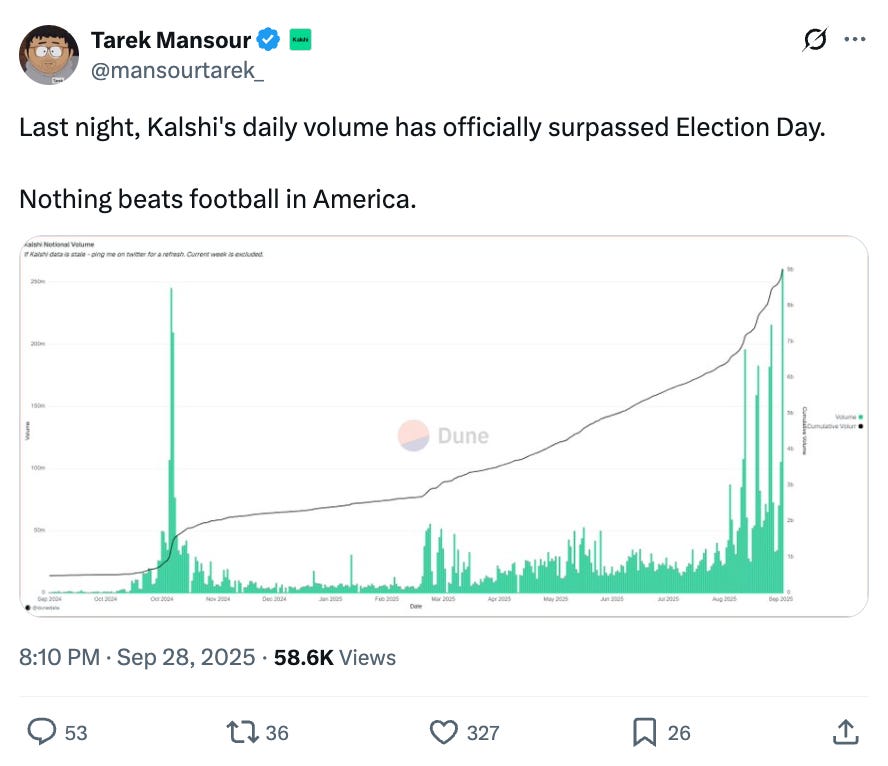

I asked Tarek Mansour, Kalshi’s co-founder and CEO, for some charts that we could include in last fall’s 10 Charts edition. He shared these three charts:

Fast forward to this week, and Kalshi has now surpassed those election highs. Check out this tweet from Tarek—who, naturally, now has a South Park-style avatar:

The rise of predictions markets is the latest in a years-long cultural and technological trend: the financialization of everything.

The Cultural Forces Behind Everything Being Financialized

Four years ago, I wrote a piece for The Atlantic called “What Happens When You’re the Investment.” That piece covered NFT mania, the GameStop craze, and the deification of Elon Musk, among other topics. It was a different time in tech: Bored Apes were selling for millions, a16z had just launched a $2.2B crypto fund, and ChatGPT was still a year away from release. But the cultural zeitgeist then was similar to today’s: there was a growing distrust of institutions and an aversion to “traditional” career paths.

When I think everything being financialized, I think about three discrete events that sowed the seeds in a new generation:

The Great Recession gave Millennials and Gen Zs a broad skepticism of the corporate ladder, as millions of people abruptly lost their jobs (including many parents of Millennials and Gen Zs).

A decade later, the pandemic provided another shock to labor markets.

And now, AI is making the job market wobble even more: many young people live in fear of AI taking their jobs, or are already having trouble finding entry-level positions. (Refer back to last month’s employment data in How to Productize AI Anxiety.)

These events collided with enabling technologies—the internet, crypto, now AI—to supercharge the capital markets and open up new avenues for wealth creation.

FAFOnomics vs. Economic Mobility

An important backdrop for this phenomenon is just how unequal the capital markets have historically been in America.

Only about 1 in 2 Americans has any exposure to the stock market, and that exposure is stratified by income: only 15% of families in the bottom 20% of income earners hold stock, while 92% of families in the top 10% of the income distribution own stock. The top 10% of income earners own 10 times as much of the stock market as the bottom 60%. And white investors own 3x as much stock as Black or Hispanic stockholders.

This meant that the economic recovery from the Great Recession largely flowed to wealthy equity-holders, while wages stagnated for salaried and hourly workers. Limited access to the capital markets has long stymied economic opportunity and mobility: it’s nearly impossible to accumulate true wealth by renting your time; you have to own equity.

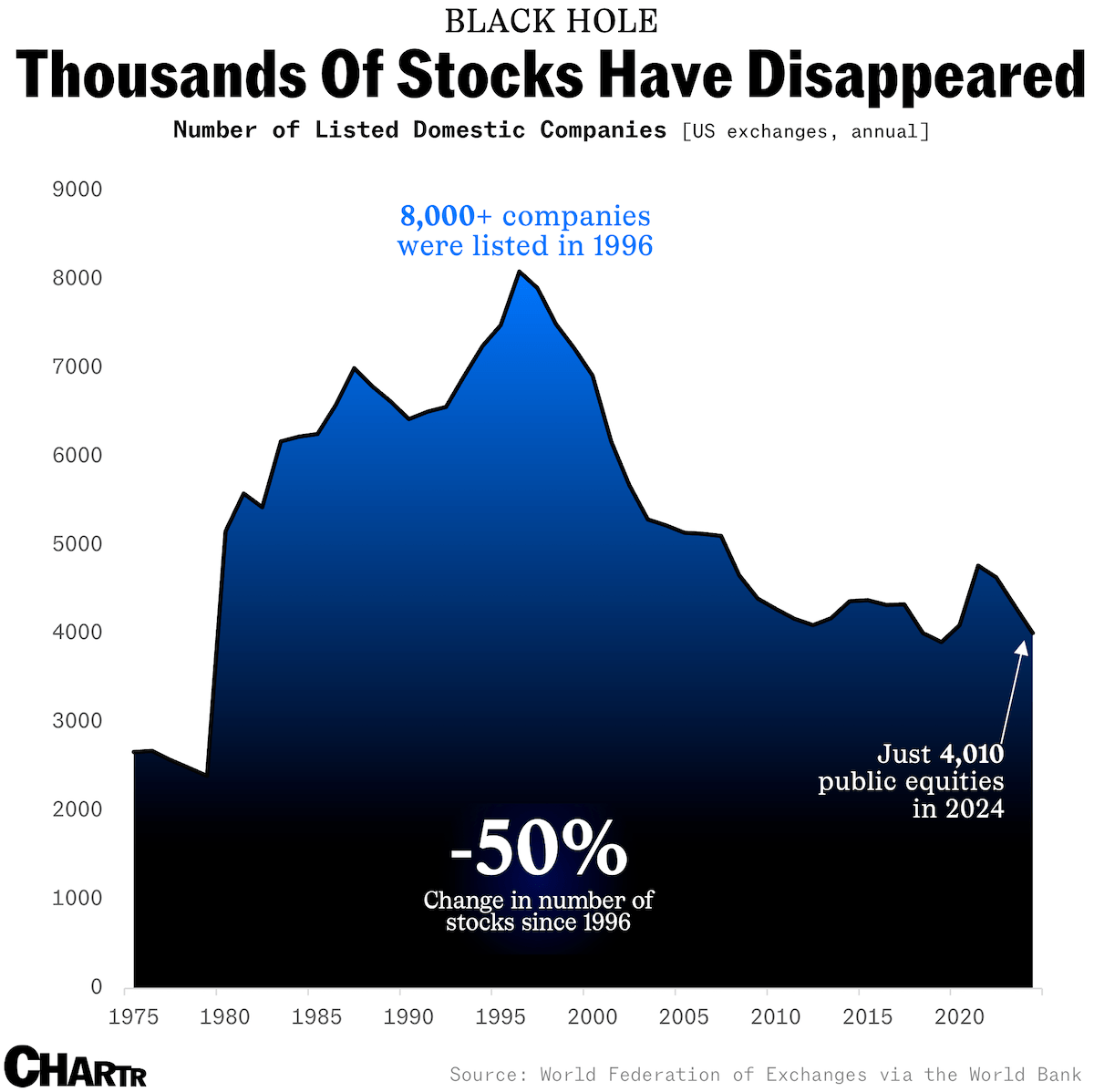

What’s more, there are now fewer public companies to even own a share of! Check out this chart of listed companies:

Today there are about half the number of U.S. public companies that were listed in 1996. Much of modern wealth creation happens in the private markets, behind closed doors: your average American isn’t getting access to Stripe or Databricks or SpaceX or Anthropic. Even with Robinhood working hard to open the private markets to Main Street, chances are slim that many Americans will accumulate real wealth from owning shares in a company.

But what if you could generate wealth by trading on stuff other than stocks?

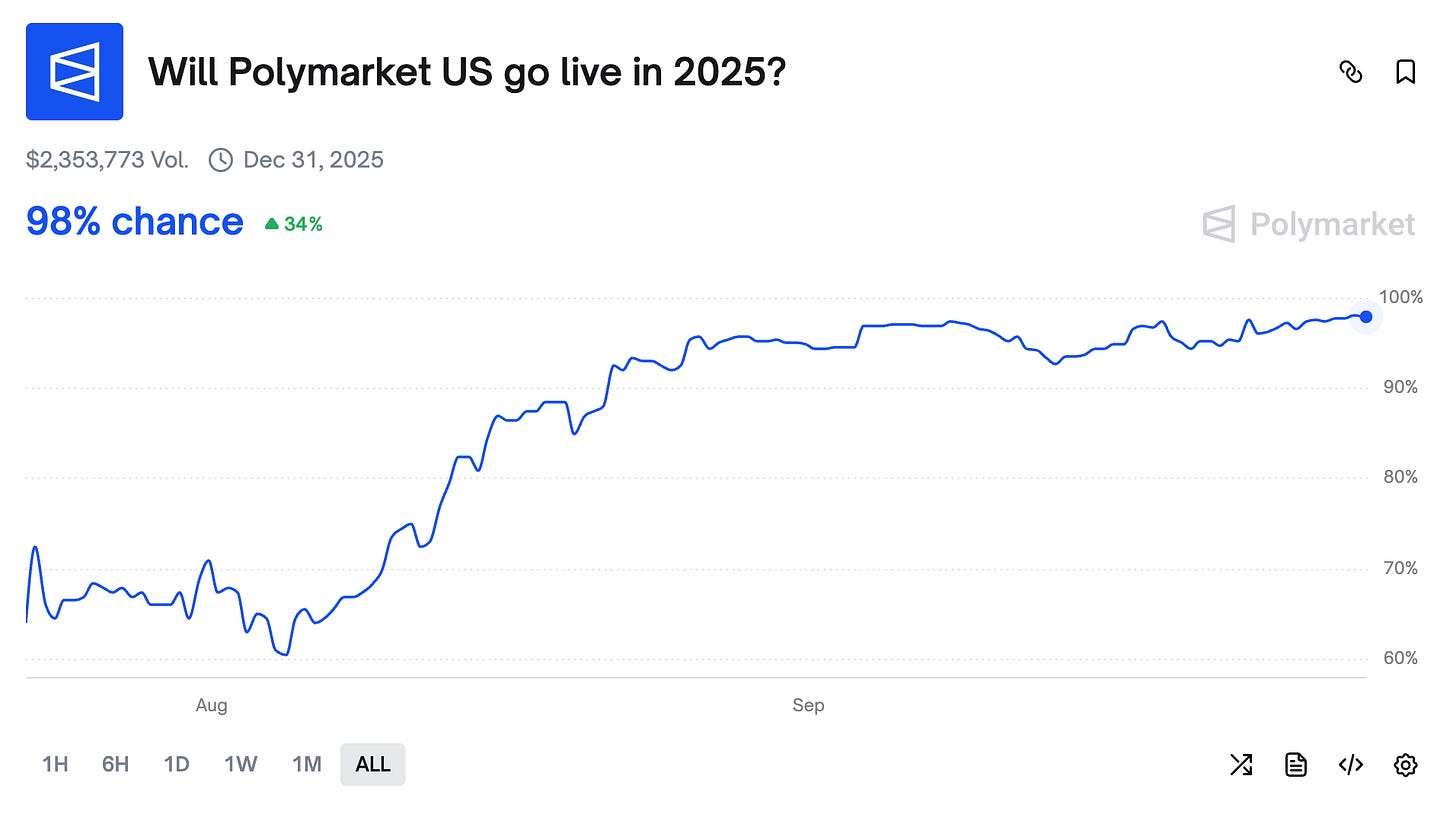

That’s what’s happening today with prediction markets. Kalshi didn’t invent the concept of “event contracts,” but it popularized them and created the first (and only) federally-regulated exchange in the U.S. where people can trade on the outcome of future events. Polymarket isn’t live in the U.S.—but the betting markets seem to think that will change soon:

Prediction markets have been around for a while. Here’s an excerpt from a July 2021 Digital Native piece:

The startup Kalshi—named for the Arabic word for “everything”—lets you invest in (almost) everything. Kalshi uses “yes” or “no” contracts to let you trade on event outcomes. If you think the unemployment rate in July will be over 7%, you can buy a “yes” contract. If you don’t think 2021 will be the planet’s hottest year on record, you can buy a “no” contract.

When we wrote this, Kalshi was still 3.5 years away from its breakthrough moment. Sometimes startups feel like overnight successes, but they’ve been grinding it out for years behind the scenes. Looking at that Kalshi trading volume in the earlier charts, it was linear for a long time until it hit escape velocity.

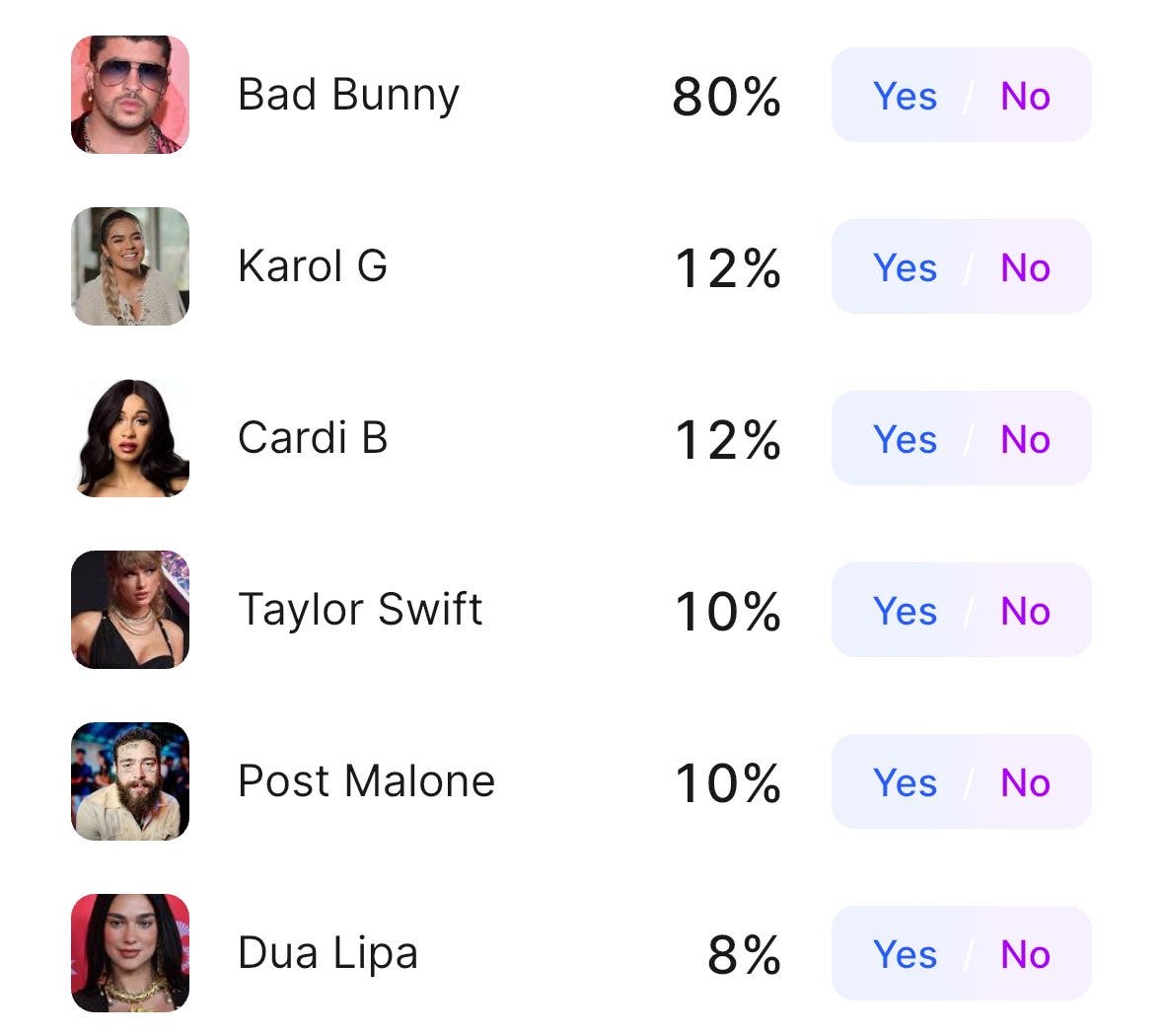

Finally, prediction markets are at their tipping point. And because of most people’s lack of access to capital markets, there’s an argument that they offer a noble savior, a vehicle for economic mobility. What if you know nothing about finance, but you’re a pop culture savant? You’re pretty sure that Bad Bunny will headline the Super Bowl; shouldn’t you be able to monetize that knowledge?

Robinhood’s Vlad Tenev put it poetically: “At the most fundamental level, [prediction markets] are the application of capitalism to the pursuit of truth. Market incentives and the wisdom of the crowds sift through all the information out there to determine answers to well-specified questions and outcomes to important events.”

But there’s the other side of the argument: that prediction markets are a great way to unleash a risky new asset class on the masses. The legalization of sports betting sparks similar controversy. One of my favorite economic commentators, Kyla Scanlon, calls this FAFOnomics—as in, “Fuck Around and Find Out.”

FAFOnomics does seem to be the approach for a new generation. Dismayed by static wages, high inflation, and a lethargic corporate ladder, millions have turned to riskier strategies with higher upside. An undercurrent of nihilism runs beneath FAFOnomics.

There’s truth, of course, in both arguments: new financial products do offer a way to generate wealth, while also presenting risks. We need good policies in place, sure, but we also need good startups to underpin new economic models.

What Startups Power This Shift?

We’ve talked a lot about Kalshi and Polymarket. Even at current valuations, I’m bullish on prediction markets. The potential upside is massive. A good Forbes article chronicles a 2023 visit to Kalshi’s offices by an 88-year-old man—someone named Charles Schwab. Schwab was fascinated by what Kalshi was working on, and he’d go on to become a key Kalshi investor and advisor. From Mansour: “Within a few minutes of my first call with Chuck, he was like ‘I want to invest.’ He said it reminded him of when he started Charles Schwab, and it was the first time in a while he had seen a company that could fundamentally change financial markets.”

For reference, Charles Schwab is a $176B market cap company today. (Its eponymous founder started it in 1971.) Clearly, there’s a lot of upside in a nascent category of finance.

But where else does the broader trend—people wanting to own equity upside—show up in Silicon Valley?

We see a younger generation eschewing traditional careers in lieu of more unpredictable work with higher potential upside. The risk-return calculus has shifted. A number of startups underpin these new forms of work. The first iteration, of course, was the creator economy: remember the stats around 60%+ kids wanting to be influencers? We saw YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram support millions of new jobs, while Shopify and Etsy, in their own ways, underpinned new forms of entrepreneurship (albeit more traditional commerce, just through a new channel).

Now we see a newer generation of players. Whop, for instance, makes it easy to sell digital products: sneaker bots, IP proxies, access to digital communities, you name it. The company is doing hundreds of millions in GMV.

Or what about AI companies that support new forms of monetizable work? Anything is a text-to-app builder that just announced its Series A this week. According to the founders, Anything already supports some interesting work:

A financial analyst has made $34K selling AI tools

A Hollywood producer made a children’s AI learning mobile app. Submitted it to the App Store, aiming for $20K MRR.

A real estate agent spun up an AI training portal, now sells $1K virtual sessions.

A medical student made a CPR training mobile app, charges $85/mo.

You can envision a lot of careers being supported by the Anythings, Lovables, and Replits of the world. People want to have financial autonomy and economic upside—whether that’s betting on NFL games or launching text-to-AI apps.

New technologies open up new avenues to earn an income (with often unbounded upside). New cultural shifts make people want to pursue these avenues for wealth creation, often at the expense of “old school” work. These forces are creating the biggest shocks to labor and capital that we’ll see in our lifetimes.

Final Thoughts

How does AI fit into this? We’ve written a lot about AI’s impact on work over the past few months, but I liked an example Derek Thompson wrote about last week. Excerpt here:

One way to think about AI’s effect on workers is asking the question: Is artificial intelligence a tractor or a spreadsheet?

When we invented tractors, the population of horses on farms plummeted, because the tractor essentially automated everything that farmers needed from a horse. If you carried forward the frame that all technology is a tractor, you would have predicted that the invention of the spreadsheet would decimate the employment of accountants and other occupations that dealt with spreadsheets. Instead, the increased efficiency of spreadsheet work turned basically the entire white-collar economy into a bunch of spreadsheet jobs, and the number of accounting, tax prep, and bookkeeping jobs has increased steadily in the age of Excel.

Jevon’s paradox is an economic theory that refers to the idea that increased efficiency leads to more consumption rather than less. In the 1800s, the UK increased the efficiency of coal-burning factories. Did the burn the same amount of coal more cheaply? No, they burned more coal. In the 2000s, the cost of producing and publishing video entertainment plummeted. Did we make the same number of videos but more cheaply? No, we made one trillion videos. So one plausible prediction about AI is not that it will replace workers but rather that the collapsing cost of using AI to generate ideas will turn everybody into insufferable influencers. Sorry, I mean knowledge workers!

Maybe AI doesn’t replace knowledge work; maybe it lowers the cost of generating ideas, content, and analysis, so much so that we all end up doing more knowledge work. Maybe this creates more jobs, and we all benefit from an increase in GDP per capital.

Maybe. We’ll see. There’s also a world where you AI does most of our “work,” while we live in a speculation economy—an economy in which everything is financialized and tradable, with the capital markets gobbling up more of life and work.

Either way, we’re seeing a massive shift in how a new generation views (1) work and (2) wealth. I expect we’ll see more Kalshi predictions, more sports betting, and more businesses launched on tech platforms. We’ll see more risk (definitely), more reward (probably), and—one can hope—some newfound economic mobility.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: