Squid Game and the Consumer Fintech Renaissance

Broadening Access to the Financial System

This is a weekly newsletter about how people and technology intersect. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Squid Game and the Consumer Fintech Revolution

Like much of the world, I spent the past week binge watching Squid Game. The show has taken the world by storm: it’s currently #1 in 90 countries, and it’s on track to be Netflix’s most-watched show ever. That’s quite a feat for a Korean-language show featuring actors little known outside Korea.

At its highest level—and with no major spoilers—Squid Game is about 456 Korean adults, each deeply in debt, who are invited to a mysterious competition. They must play children’s games (for example, the first game is “Red Light, Green Light”) for a chance to win a lot of money. If they don’t advance past each of the six competitions, they die.

On the surface, Squid Game is a bloody, Hunger Games-style thriller. But on a deeper level, it’s a dark and biting social satire—a commentary on income inequality more comparable to its Oscar-winning Korean peer Parasite. As Brian Phillips at The Ringer puts it: “Get Out used horror to anatomize American racism; Squid Game uses the survival thriller to anatomize economic exploitation.” Each character in Squid Game has been chewed up and spat out by the financial system, exploited by loan sharks and hidden fees. One distinction from battle royale stories like The Hunger Games is that each participant in Squid Game chooses to be there. Players are given the option to leave but opt to stay in the game; participating in a to-the-death competition for a shot at being rich is more palatable than going back to their lives in the real world.

Squid Game hits on an important truth: the financial system isn’t equal. It’s built to exploit the poor and indebted. JPMorgan Chase makes over $2 billion a year from overdraft charges. The average overdraft fee grew 54% from 1998 to 2018, and Americans as a whole paid $34 billion in overdraft fees in 2017. For many regional banks, bank fees make up 40% of all revenue. Check-cashing businesses, meanwhile, generate $790 million in fees every year—and it’s estimated that an unbanked worker earning $22,000 a year spends $800 to $900 a year (!) in cash-checking fees alone. The system is even less equal for communities of color. Minimum opening deposit requirements and checking account fees are both significantly higher in communities of color than in white neighborhoods.

The results of a broken financial system are staggering. In America, 25% of the population is unbanked or underbanked. A survey from the Federal Reserve revealed that 50% of Americans would struggle to pay a $400 emergency expense; 19% wouldn’t be able to come up with the money at all. The average borrower now takes 20 years—20 years—to pay off a college student loan.

The financial system isn’t going anywhere—it’s the central nervous system of our economy. The political theorist Fredric Jameson once said, “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.” But our current model of capitalism is broken. The fintech revolution is about building more convenient and more accessible financial products for people.

We’re particularly in a consumer fintech renaissance, with elegant, design-first products demystifying finance and opening the system to more participants. This is happening in how we bank, in how we save and invest, and in how we buy stuff.

Banking

A neobank is a type of bank that exists only online. You can’t visit your local branch of a neobank; it exists only in the cloud. The term was popularized around 2017 and encompasses digital banks like Monzo, Varo, and Current. In 2021, 30 million Americans have accounts with neobanks; by 2025, this will swell to 54 million.

The largest neobank in the U.S. is Chime, which has grown to ~13 million accounts by offering no-fee banking. Unlike many “traditional” banks, Chime makes no money through exploitative fees. (Instead, Chime makes money primarily through interchange—essentially the amount merchants have to pay Visa and Chime when they accept a credit or debit card.)

In the last few years, neobanks have emerged to serve various slices of the population. Chime focuses mainly on lower-income customers. Step focuses on teenagers. Greenlight focuses on young kids.

With such a crowded environment, marketing is paramount. Many of the teams behind these companies have strong marketing backgrounds, and some have used clever tactics to stand out. Step, for instance, counts Charli D’Amelio as an investor and brand ambassador. Having a 17-year-old with 120 million TikTok followers on your cap table helps when you’re trying to win over teens.

Each of these neobanks provides a better experience for consumers—fewer fees, a more elegant UI, less staid marketing. And the arc of consumer technology bends toward what is more affordable, more convenient, and more enjoyable for the end user.

Investing and Personal Finance

The rise of the internet coincided with the rise of income inequality. The Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality, has swelled from 0.43 in the mid-90s to 0.49 today—its highest level in history. The combination of the internet and income inequality birthed the personal finance industry, a multi-billion-dollar industry that took hold in the 90s and early 2000s. Books like Rich Dad, Poor Dad soared to the top of the charts. Millions of people blogged about their budgets. And financial advisors like Suze Orman became bona fide celebrities. The Suze Orman Show ran on CNBC from 2002 to 2015 and Orman was even parodied on SNL by Kirsten Wiig.

The last decade brought products designed to help people save. Acorns, for instance, rounds up your purchases and invests the spare change. If you buy a $3.50 coffee, $0.50 is automatically invested through Acorns.

We’ve also seen the rise of commission-free investing apps that aim to democratize investing. A key fact underpinning inequality is that millions of Americans don’t own stock. Only about 1 in 2 Americans has any exposure to the stock market, and that exposure is stratified by income: only 15% of families in the bottom 20% of income earners hold stock, while 92% of families in the top 10% of the income distribution own stock. The top 10% of income earners own 10 times as much of the stock market as the bottom 60%, and white investors own 3x as much stock as Black or Hispanic stockholders. These investing apps hope to change that.

Investing is also now a social pastime. The r/WallStreetBets subreddit has 10.9 million members. Companies like Public and Commonstock have emerged to make investing transparent, collective, and accessible to everyone.

Companies like Stonks are doing the same for the private markets. Stonks bills itself as “YC Demo Day for everyone” and lets startups pitch viewers, who then have the chance to invest. A more mainstream tagline would be “Shark Tank for everyone.” Access to private investment has historically been reserved for people with connections. Stonks aims to change that: its website even shows how much you would’ve made as an early investor into iconic tech companies like Uber, Coinbase, and Airbnb.

Less attention has been paid to startups that let other people manage your money. But in 2020, 65% of Americans reported not having a financial advisor, with cost the most-cited prohibiting factor. Companies like Titan are changing this. Titan invests your money on your behalf—it’s like investing in a high-performing hedge fund. In the company’s words: “Wall Street ignores everyday investors, catering to only the ultra wealthy. This divide didn’t sit well with us, so we built Titan: a premier investment manager for the rest of us.”

Companies like Vise target a different segment of the market, selling into investment managers. Vise doesn’t sell into the big money managers; rather, it provides a portfolio management platform for medium-sized investment managers. Your mom-and-pop financial advisory firm might use Vise, closing the gap on major investment managers.

All of these companies—whether they let you invest directly, let you invest through a manager, or help you manage your personal finances—share a common purpose. They want to level the playing field. They’re turning financial products that have historically been arcane and inaccessible into products available to everyone.

Making Purchases

For the better part of a decade, pundits have been predicting the decline of credit cards. Back in 2013, an article titled The Slow Death of Credit Cards announced:

Great news: Americans are giving up on one of the most ruthless destroyers of wealth the numerically challenged have ever known: credit cards. We’re more interested in debit cards these days. Old style American consumerism, one built on debt, may be coming to an end. Good riddance, credit cards.

And yet, credit card debt swelled from $660 billion in Q1 2013 to $930 billion in Q4 2019. In 2016, less than a third of Millennials had a credit card; now two-thirds do, and 40% have two or more. Among Gen Zs—who are often predicted to forgo credit for debit—57% have a credit card and 25% have two or more.

Neobanks like Chime have been clever with “credit builder” cards. Chime automatically pays off your credit card balance every month, then reports the payment to the major credit bureaus. Your credit gets a boost. These builder cards have helped propel credit cards.

Another major driver of credit card growth is the allure of credit card rewards. But some innovative startups are taking the concept of rewards and bringing it to debit cards. Point, for example, offers Millennial-friendly and Gen Z-friendly rewards with its debit card: 5x points on subscriptions to Netflix and Spotify, 3x points on DoorDash and Uber, and so on.

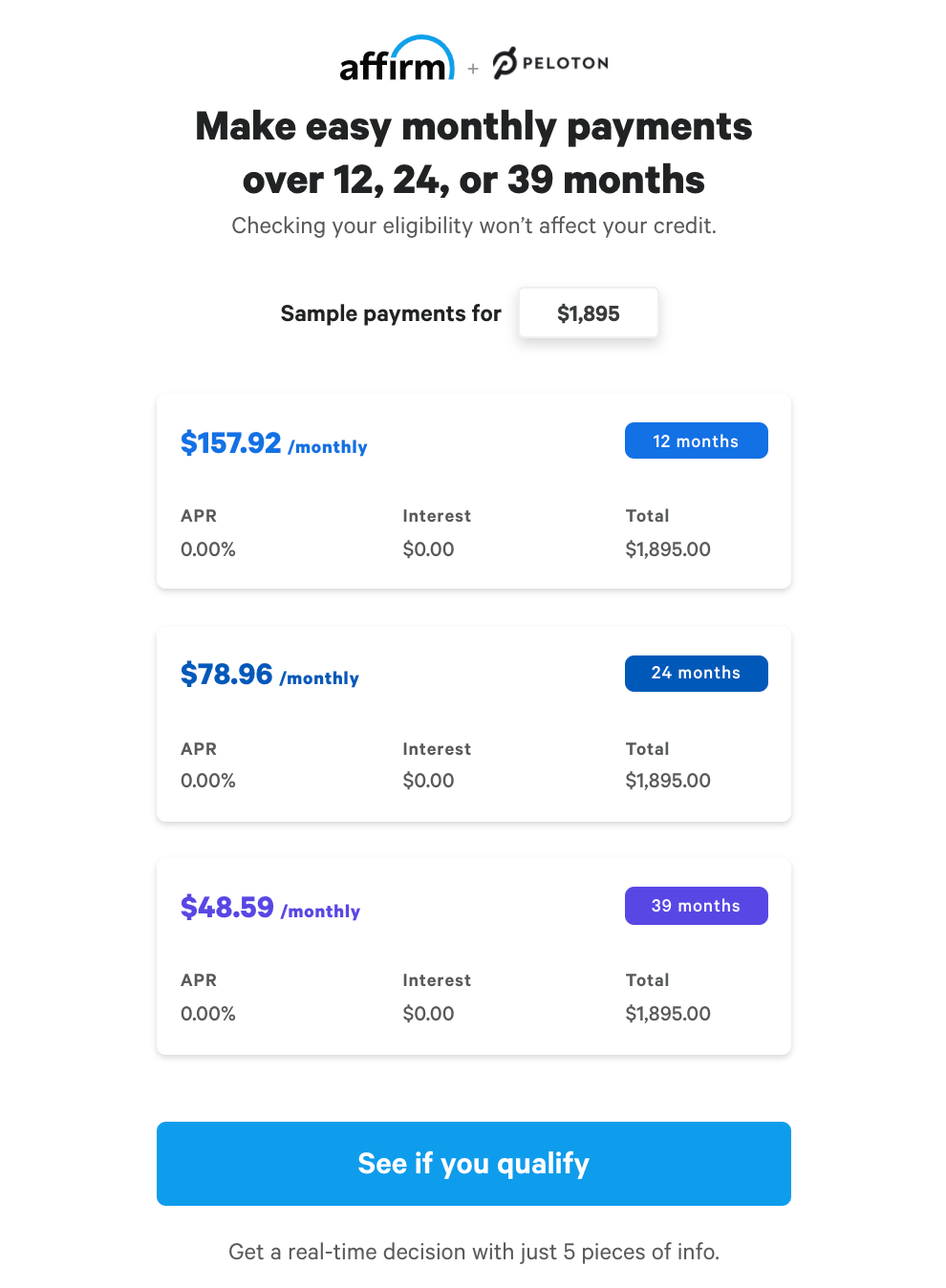

But the biggest disrupter to how we buy stuff has been BNPL, or “Buy Now, Pay Later.” BNPL essentially lets consumers borrow money toward a purchase, and then repay the purchase price in installments (typically four installments). For instance, here’s what it looks like to buy a Peloton using Affirm:

(As a side note, Peloton accounted for 28% of Affirm’s revenue at the time of IPO last year.)

BNPL is a serious threat to credit cards: 7 in 10 BNPL users prefer BNPL to credit cards; 59% say they would happily replace their credit cards with BNPL; and 57% say they find it easier to manage multiple BNPL plans than to manage credit card statements.

And BNPL is catching on fast. Over half of consumers report using a BNPL service.

A third of BNPL users starting since Covid began, 71% have increased their use in the last 12 months, and 78% expect to increase use in the future.

BNPL is having a moment, with Affirm’s IPO ($30 billion market cap), Afterpay’s sale to Square ($29 billion), and Klarna’s new title as the most valuable startup in Europe ($46 billion). But BNPL has a ways to go to supplant credit cards. Of those who haven’t used BNPL, 30% point to the lack of rewards while 30% say they prefer their debit card. But the big BNPL players will start to resemble full-fledged, diversified financial institutions in the coming years: Affirm has already announced plans for a debit card, and Klarna launched consumer banking in Germany earlier this year.

The continued strength of credit cards and the rise of BNPL are, in many ways, antithetical to the narrative of a younger generation preferring the less dangerous, less predatory debit. That narrative may still prove to be true over the coming decades, but early indications are that credit products remain formidable.

Final Thoughts

In Squid Game, the Front Man is the person running the games—keeping players in check and ensuring everything goes according to plan. Beyond having a super cool outfit that I may or may not be emulating for Halloween, the Front Man is a metaphor: he embodies the exploitative financial system.

America’s middle class has all but disappeared: 87% percent of U.S. adults have less than $10,000 to their name. The goal of the consumer fintech movement is to fix that. Fintech is about building better, faster, cheaper products that bring more people into the financial system.

Sources & Additional Reading

How Predatory Banking Fees Are Zapping Our Wealth | Casey Bond

The Debit Card Explosion Is Going to Fizzle | Ron Shevlin, Forbes

Why Financial Confessionals Go Viral | Annie Lowrey, The Atlantic

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox each week: