Stay for Who You Can Be: Avatars in the Metaverse

How Digital Avatars Influence Our Behavior

This is a weekly newsletter about how people and technology intersect. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Stay for Who You Can Be: Avatars in the Metaverse

Ernest Cline’s 2011 science-fiction novel Ready Player One—turned into a 2018 film by Steven Spielberg—takes place in 2045, when our planet has been gripped by an energy crisis and rampant climate change. With the physical world crumbling, humans spend most of their waking hours in the OASIS, an immersive virtual reality universe. The OASIS has become mankind’s playground. In the protagonist’s words:

The OASIS is a place where the limits of reality are your own imagination. You can do anything, go anywhere. Like the Vacation Planet. You can surf a 50-foot monster wave in Hawaii, you can ski down the Pyramids, you can climb Mount Everest with Batman.

Then, the protagonist says something profound:

People come to the OASIS for all the things they can do, but they stay because of all the things they can be.

They stay because of all the things they can be. I think about that sentence a lot.

Today, we’re spending more time than ever online: the average American adult spends 11 hours interacting with digital media every day. Immersive virtual worlds command an increasing portion of that time. Roblox daily active users, for instance, spend almost three hours a day in Roblox; framed differently, that’s about 1 in 6 waking hours.

In these virtual worlds, we take the form of avatars—digital representations of ourselves. The word “avatar” originates from Hinduism, where it stands for the “descent” of a deity into terrestrial form. In 1985, the video game developer Richard Garriott used the word to refer to his player in a video game—Garriott wanted his player’s character to be his Earth self manifested into the virtual world. The term caught on and is today used broadly across popular culture—from Ready Player One, to Nintendo’s Wii, to James Cameron’s Avatar.

As we spend more time as avatars, it’s worth asking some questions: What does it mean to take a digital form? And how does that digital identity change our perception of both ourselves and others?

The Proteus Effect

The Proteus Effect is the phenomenon that our behaviors within virtual worlds are influenced by the characteristics of our avatar.

Stanford’s Jeremy Bailenson and Nick Yee are the leading researchers on The Proteus Effect. In their seminal study, they showed that both an avatar’s attractiveness level and height influenced behavior:

Participants assigned to more attractive avatars were more intimate and open with other participants. They both stood closer (virtually) to other participants and disclosed more about themselves.

Participants assigned to a taller avatar behaved more confidently in a negotiation task and showed more assertive, dominant behaviors.

Bailenson and Yee later tested whether these online identities translated to offline interactions. They did. Bailenson and Yee wrote: “In addition to causing a behavioral difference within the virtual environment, we found that participants given taller avatars negotiated more aggressively in subsequent face-to-face interactions than participants given shorter avatars.”

In the 1970s, researchers showed that people’s clothing can affect behavior. Wearing a lab coat and holding a clipboard, for instance, make doctors more decisive and effective. Candidates who wear professional attire to job interviews perform better. But digital worlds magnify these effects. As Bailenson and Yee put it: “In online environments, the avatar is not simply a uniform that is worn—the avatar is our entire self-representation.”

The Proteus Effect is named for the Greek god Proteus, who could shape shift into whatever form he pleased. Digital worlds give us Proteus-like powers: the ability to rapidly and dramatically change our likeness at unprecedented speed and scale.

As we spend more time as avatars, the Proteus Effect will become more fundamental to how we communicate and interact.

Implications of the Proteus Effect

There are 350 million global Fortnite players who have collectively played Fortnite for 10.4 million years—more than twice as long as human ancestors have been on Earth.

That means that people have spent 10.4 million years—91 billion hours—as avatars within Fortnite’s virtual world.

It’s interesting to think about how those hours spent as avatars have changed people’s self-worth or influenced the friendships built within Fortnite’s world. If you spend 20 hours a week as Deadpool, do you take on his brashness in your real-world interactions?

Digital personas are broader than gaming. Bitmoji, founded in 2014 and acquired by Snapchat in 2016, lets people easily communicate with avatars in messages. Apple’s Memoji is a more recent example. Many of these platforms default to young, thin, and attractive avatars, which Bailenson and Yee emphasize may lead to more intimate online interactions:

In many of these environments, the only avatar choices are youthful, in shape, and attractive. If having an attractive avatar can increase a person’s confidence and their degree of self-disclosure within minutes, then this has substantial implications for users in virtual environments. When thousands of users interact, most of whom have chosen attractive avatars, the virtual community may become more friendly and intimate. This may impact the likelihood of relationship formation online.

Last week, Mark Zuckerberg gave an interview about Facebook’s virtual reality ambitions and touched on Oculus’ new avatar creation system:

Part of it is, we’re building out this avatar system that is going to get increasingly expressive on the one hand, and then if you want, also increasingly realistic. Although I think not everyone wants to be exactly realistic all the time, so you want to kind of offer both expressive and realistic.

That tradeoff between expressive and realistic gets to the crux of avatars: people get to choose who they want to be. Avatars can hew closely to your offline representation, or they can be completely aspirational. Oculus’ press release announcing the avatar editor underscores its customizability:

The new Avatars support over one quintillion permutations (that’s 18 zeros if you’re counting) so hopefully your Avatar will be more “You” than ever before.

One quintillion! 😯

Zuckerberg also emphasized how avatars let you better empathize with other people:

One view on communication technology is that they’re basically technologies around sharing a perspective. Some people describe books that way. Basically, books are a technology for sharing a perspective and trying to internalize someone else’s perspective. And there's certainly film, and other things try to do that well. But in a lot of ways, I think virtual reality is the ultimate, because it literally lets you embody someone and walk in their shoes, and experience some of what they’re actually seeing and feeling around them. So I think that’s going to be pretty powerful for not just school-type learning, but culture and sharing each other’s experiences, and getting more empathy for what other people are experiencing around the world as well.

This is a powerful idea—you can imagine the possible use cases, from early-childhood education to corporate diversity training. But there are also complicated ethical questions to answer. What does it mean to “try on” someone else? “Digital blackface”—the concept of non-Black people using the images and voices of Black people to explain emotions or phenomena—is already a concern with reaction GIFs. As people spend more time in avatar form—and have more power to customize their avatars—these questions will become more pressing.

There’s a robust economy forming around avatars. Non-fungible tokens are a key enabling technology: smart contracts offer provable scarcity, letting you own exclusive digital goods. One example is RTFKT, which brings sneaker mania to the digital realm:

The top sneakers on RTFKT sell for thousands of dollars.

The next project from Dapper Labs—the maker of CryptoKitties and NBA Top Shot, as well as the Flow blockchain—is an avatar partnership with Genies. Genies will let you design your own 3D avatar and then buy tokenized digital clothing and accessories for your avatar.

Celebrities like Shawn Mendes, Cardi B, and Justin Bieber have already worked with Genies (all three are in the image below, if you can spot them) and the Dapper Labs partnership will expand access to everyone.

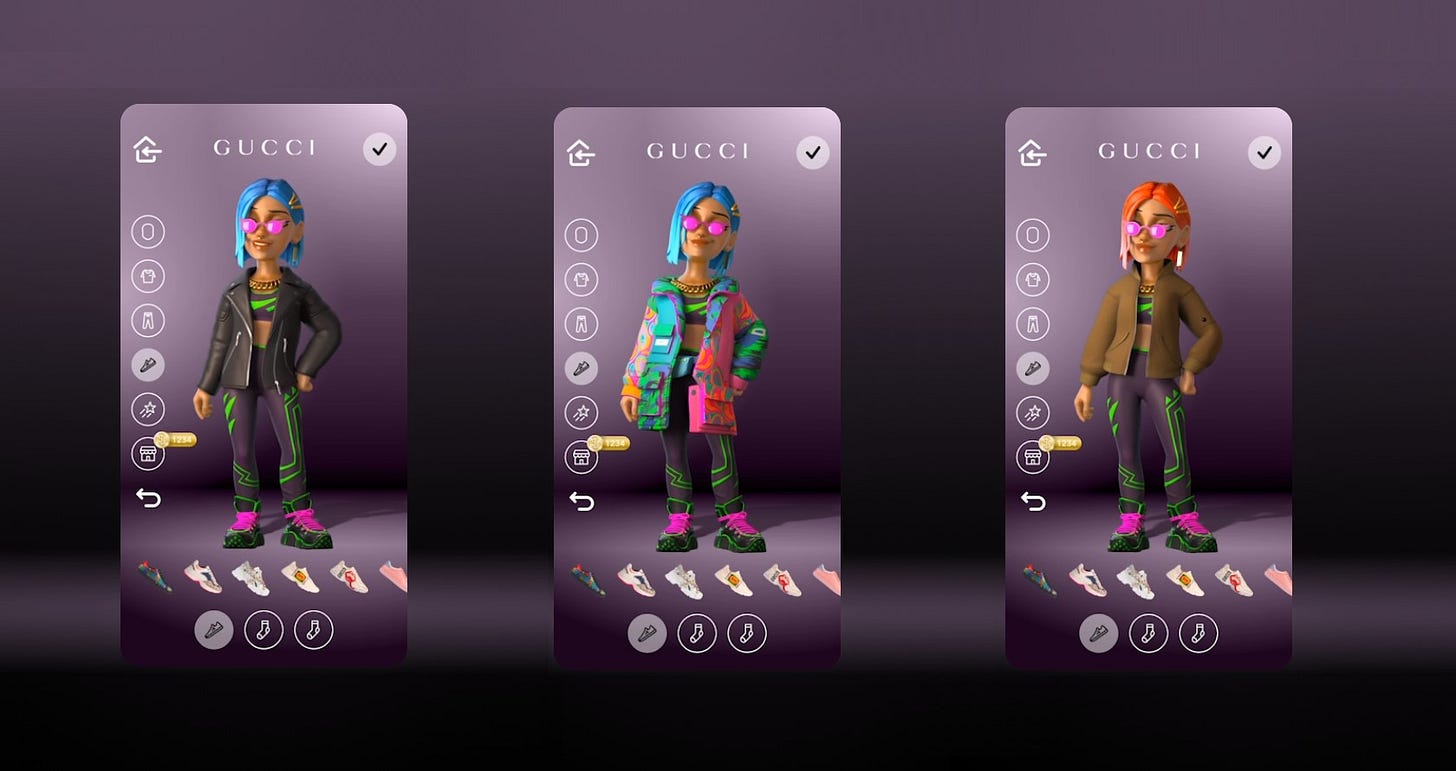

“Traditional” brands are getting in on it too: Gucci is working with Genies to sell clothing for avatars. Genies’ founder, Akash Nigam, again emphasizes expression:

“The point is not to have an avatar that is representative of who you are. It’s not who you are in the real world. It’s the aspirational version of yourself. [Users] want to create something that feels like what they authentically believe they are on the inside. It reveals a lot about their personality and feelings.”

In The Rise of Synthetic Media and Digital Creators, I wrote about Miko and how she’s sculpted a unique digital persona.

In the same vein, avatars let people express themselves in new ways—particularly people who may be more private and prefer to communicate through a digital character rather than through video or real-world interactions. Interacting through avatars and virtual worlds will unlock a new era of self-expression and facilitate new forms of digital relationships.

Final Thoughts

We’re not quite in Ready Player One territory yet. No one’s built the OASIS.

But we’re spending a stunning amount of time in virtual worlds. The OASIS may seem far-fetched, but today’s pace of innovation is staggering. When I was a kid, Mario Kart was considered innovative; today’s kids build expansive and complex virtual universes. In 2019, VR software sales hit an inflection point, meaning that VR is finally maturing as a platform.

As Tim Sweeney puts it: “I’ve never met a skeptic of virtual reality who has tried it.”

We’re seeing a new generation of virtual worlds emerge. Manticore Games is building “a digital playground and community designed to unleash imagination and explore new play experiences.” Sound like the OASIS? Not to be outdone, Facebook is building Facebook Horizon with metaverse ambitions. And then there are crypto worlds like Decentraland and Cryptovoxels.

At Index, we’ve seen the emergence of immersive digital worlds through our investments in Roblox and Rec Room. And we’ve seen virtual worlds move beyond entertainment—Gather lets people interact for virtual work and virtual events through their avatars in customizable digital spaces.

The lines are blurring between consumer and enterprise—during the pandemic, people took business meetings in Animal Crossing and bonded with coworkers by robbing banks together in Grand Theft Auto.

Over the next decade, we’ll spend more time in digital realms—both professionally and personally—with more control over our digital representations. The Proteus Effect will take hold. How we embody avatars will meaningfully influence how we think of ourselves, how we interact with others, and how we behave in the physical world.

We’ll come to these digital worlds for what we can do, but we’ll stay for who we can be.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Proteus Effect | Bailenson & Yee

Oculus Rolls Out New Avatar Editor | The Verge

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox each week: