The Age of Access: Capitalism Collides With Culture

Commoditizing Human Time and Creativity

This is a weekly newsletter about how people and technology intersect. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

The Age of Access: Capitalism Collides With Culture

In 1851, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote:

Is it a fact—or have I dreamt it—that, by means of electricity, the world of matter has become a great nerve, vibrating thousands of miles in a breathless point of time? Rather, the round globe is a vast head, a brain, instinct with intelligence!

Hawthorne was writing about the telegraph, but his words resonate even more in a world connected by the internet. Hawthorne’s words inspired the philosopher Teilhard de Chardin a century later, who wrote in 1941 that technology would create “a nervous system for humanity…a single, organized, unbroken membrane over the earth.”

And de Chardin, in turn, inspired Marshall McLuhan (perhaps my favorite philosopher of technology), who wrote extensively about how the emerging global network of connected technology mimicked the human body’s central nervous system.

McLuhan is most famous for popularizing the phrase “the medium is the message”, arguing that the technologies through which we communicate are even more formative than the content of our communications. He wrote, “We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us.” In The Two-Way Mirror of Art and Technology, I explored how we’ve seen this manifest over the past 50 years—from television to the internet to mobile.

Lately—in case it wasn’t already obvious—I’ve been spending time reading works written during previous eras of technology. Viewed through today’s lens, old frameworks and predictions remain strikingly relevant.

Today’s pace of change is stunning. Everything feels like it’s accelerating at once—from GPT-3 to DeFi, vTubers to Dogecoin, mRNA vaccines to commercial spaceflight. In 2020, the market caps of the big five tech companies—Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Facebook—swelled nearly $3 trillion. Their combined market cap of $7.5 trillion now exceeds the GDP of Japan, the world’s third-largest economy. A decade ago, those five companies were collectively worth under $1 trillion. And in the startup world, the first half of 2021 saw $288 billion of venture capital invested—up over 2x year-over-year. More companies have gone public at $10B+ valuations in the first seven months of this year than in all of 2020. In 2011, 16 unicorns (billion-dollar startups) were created; so far this year, 291 new unicorns have been minted—already surpassing 2020’s final count of 175.

Things will only get crazier. Packy at Not Boring characterizes this as Compounding Crazy, pointing to one of my favorite WaitButWhy graphics:

Things are moving so quickly that you can almost feel the g-forces pressing down on your body. And yet, looking back on human history shows us that the pace of innovation only ever increases in faster and faster cycles of change.

There’s one work that I’ve found particularly relevant to this moment in time. Back in 2000, the economist Jeremy Rifkin wrote a book called The Age of Access. Rifkin argues that in the Industrial Age, human labor focused on the production of goods and the performance of basic services. But software replaces human labor—first in agriculture, then in manufacturing, and finally in services. We’re in that last stage today. This is what I wrote about in The Age of Automation back in January: artificial intelligence and machine learning are rapidly obfuscating human labor. When I think of how automation is changing work, I often think of this 2020 image of a robot replacing hotel labor:

Or I think of another recent, timely, pandemic-born example: QR codes and mobile ordering replacing waiters at restaurants.

As technology takes over more of the production of goods and services, humans are turning to more creative work. “Creative work” can be defined loosely; in some ways, it encompasses the world’s 1 billion knowledge workers. A recent Deloitte report on The Future of the Creative Economy offers a broad definition of creative workers, ranging from architects to designers to engineers to advertising executives. The story of the 20th Century was a shift from manufacturing work to office work; the story of the 21st will be a shift from office work to more flexible, self-directed, creative work.

Rifkin calls this “paid cultural work in the commercial arena.” Of course, Rifkin was writing in a different era: AOL and Time Warner finalized their $182 billion merger (RIP 🪦) while his book was awaiting publication. Mark Zuckerberg was still a high school sophomore. But Rifkin’s writing is surprisingly prescient:

The capitalist journey, which began with the commodification of space and material, is ending with the commodification of human time and duration…Imagine a world where virtually every activity outside the confines of family relations is a paid-for experience, a world in which traditional reciprocal obligations and expectations—mediated by feelings of faith, empathy, and solidarity—are replaced by contractual relations in the form of paid memberships, subscriptions, admission charges, retainers, and fees.

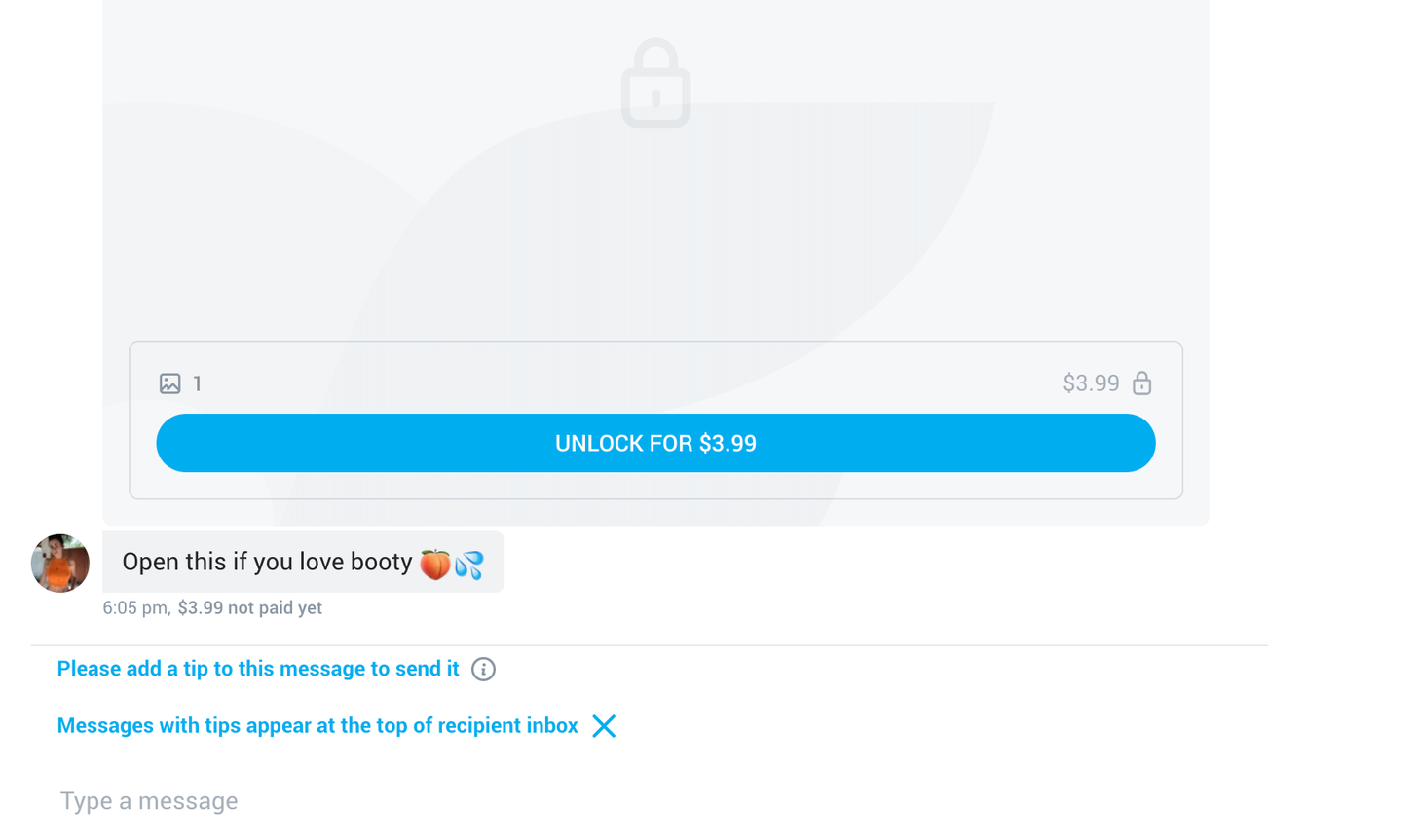

In some ways, that description sounds a lot like today’s world. You subscribe to your favorite writer on Substack and are a patron to your favorite creator on Patreon. You pay a subscription to OneMedical for your health, to MasterClass for your education, to Netflix for your entertainment. You might even seek paid intimacy on OnlyFans.

There are startups taking the concept of “paid-for experience” a step further—often controversially. The company NewNew calls itself “the Control My Life app” and lets people vote on other people’s actions:

When writer Brandon Wong recently couldn’t decide what takeaway to order one evening, he asked his followers on social media app NewNew to choose for him.

Those that wanted to get involved in the 24-year-old’s dinner dilemma paid $5 to vote in a poll, and the majority verdict was that he should go for Korean food, so that was what he bought.

“I couldn’t decide between Chinese or Korean, so it was very helpful,” says Mr. Wong, who lives in Edmonton, Canada. “I have also used NewNew polls to decide what clothes I should wear that day, and lots of other personal stuff. I joined back in March, and I post polls three or four times a week. I’ve now had more than 1,700 total votes.”

Decisions on NewNew range from “Should I get a haircut?” to “Should I break up with my boyfriend?”

NewNew is an extreme, with flavors of a Black Mirror episode, but it embodies Rifkin’s driving question: “What happens to the essential nature of human existence when it is sucked into an all-encompassing web of commercial relationships?”

Rifkin argues that the industrial era was about the commodification of work, while the Age of Access is about the commodification of play. A dozen years before YouTube introduced the world to the word “creator” (replacing the term “YouTube stars”), and a half-dozen years before Facebook cemented our modern understanding of social media, Rifkin anticipated this collision of capitalism and culture:

The waning blue and white collar work will be replaced by opportunities in cultural work. The commodification of relationships means that people will buy the time, attention, and affection of other people.

With our work being done by computers, humans are freed to focus on culture—and that culture becomes pecuniary.

The major cultural platforms are leaning into access-focused commerce. Twitter launched Super Follows to let you charge for tweets. TikTok’s Cameo-like Shoutout feature—similar to the startup Pearpop—lets users pay for interactions with other users. And Instagram may let creators paywall their Stories, formalizing the hack of asking followers to Venmo you for access to your “Close Friends”.

Access is becoming both more sought after and more monetizable. In Rifkin’s words:

Now, the economy has turned its attention to the last remaining independent sphere of human activity, the culture, with an eye toward making human experience itself the ultimate commodity.

Last New Year’s, I wrote We’re All Social Distancing Online Too. The basic premise was that as we’re all sheltering-in-place during COVID in the physical world, we’re also isolating in our proverbial online homes. As culture collides with capitalism, it fragments. Mass media is a 20th-century phenomenon; today’s media is niche and algorithmic.

The Age of Access exacerbates this. As more experiences go behind a paywall, more of culture will splinter. I might subscribe to HBO Max, while you pay for Disney+. I pay for Andrew Sullivan’s Substack, while you’re subscribed to The Dispatch. Instead of the family crowding around the TV for M*A*S*H every night, family members retreat to their own screens: Dad watches Tucker Carlson, Mom tunes into Samantha Bee, and the kids are glued to JoJo Siwa.

The ad-supported internet remained free and accessible to all. But as the internet shifts from ad-based models to subscriptions and fees and tickets and microtransactions—as evidenced by the earlier examples with Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram—more content becomes inaccessible. Many people already argue that The New York Times can no longer be the “paper of record” because it now sits behind a paywall.

The fragmentation of culture is a long and steady trend. The advent of television shattered the common language of film: Americans used to go to over 50 (!) movies a year; but between 1946 and 1956, as TVs penetrated households, box office receipts fell by 40% and attendance dropped 50%. Then cable did the same thing to broadcast—all of a sudden, three channels exploded into 300. And, of course, the internet shattered whatever common cultural language remained.

To be clear, the shift from advertising to commerce is a positive shift—creators can better earn a living and privacy can again be valued. (McLuhan had another great quote that warned of invasive ad-targeting: “Once we have surrendered our senses and nervous systems to the private manipulation of those who would try to benefit from taking a lease on our eyes and ears and nerves, we don’t really have any rights left.”) The fragmentation of culture is also not a negative: more people can be the arbiters of culture—equipped with better tools and distribution—and consumers can tap into richer, deeper niches tailored to their interests. What’s important, though, is to parse the lines between commercialism and culture. Rifkin warns that communications, communion, and commerce will become indistinguishable. Keeping them distinct—to the extent we can—gives us the benefits of this new creative economy while preserving the richness of non-transactional human relationships.

Final Thoughts

It’s easy to view the collision of culture and capitalism—the age of access—through a pessimistic lens. Rifkin certainly does: The Times even called him “a leading techno-pessimist.” Some aspects of the dystopian portrait he painted in 2000 ring even more true in 2021. Parts of our lives are becoming more financialized and commoditized, everything a paid-for experience.

But technology has also been a massively powerful and overwhelmingly positive force since Rifkin wrote The Age of Access. When the book came out, 50% of the human race had never placed a phone call. Twenty years later, 5.27 billion people have a cell phone—66.85% of the world’s population. About 50% of the world has a smartphone. In a relatively short time period, we went from half the world having never placed a phone call to half the world having a supercomputer in their pocket.

The world has already shifted from a 20th-Century production-based capitalistic economy to a 21st-Century network economy. Marketplaces for physical goods have become marketplaces for ideas and information. The next iteration is an access economy—a marketplace for access to people and their time. As long as we safeguard what access is paid versus what remains free, this new economy should unlock more wealth creation and economic mobility.

McLuhan’s writing often focused on how technology is an extension of our bodies. The wheel extends our feet, the phone extends our voice, television extends our eyes and ears, the computer extends our brain, and electronic media, in general, extends our central nervous system. We’re in a moment in time where technological innovations are happening at an unprecedented rate. We just need to retain some agency over how the tools that we create shape us.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Age of Access | Jeremy Rifkin

The Creative Economy | Deloitte

Teaching McLuhan | David Bobbitt

Hawthorne, McLuhan, and de Chardin | The Frailest Thing

Related Digital Native pieces:

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox each week: