The Art of the Deal: How Money Shapes Art

When Creativity Bleeds Into Commerce

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

The Art of the Deal: How Money Shapes Art

The modern art industry can be traced back to October 18, 1973.

That day in history has become known as “the Scull sale”—the day that Robert Scull, a New York taxi-fleet magnate, auctioned off his prized art collection for an outrageous and (to many) offensive sum. Scull sold 50 of his most prized works at a Sotheby auction. Brazenly, Scull—a talented self-promoter—marketed the event as a must-see attraction. The New York art community was horrified. Art had never been so financialized; the art world had never seen such prices. Jasper Johns’ “Target”, for instance, sold that day for $135,000. (The painting is currently owned by Stefan Edlis, who bought it in 1997 for $10 million and who says it’s now worth $100 million.)

That October day was the day that, in many ways, art became about money. Or, at the very least, the two became even more inextricably bound. Art has, after all, always had a close, delicate, and complicated relationship with money.

In his HBO documentary The Price of Everything, the filmmaker Nathaniel Kahn explores how money and art intersect. Kahn enjoys access to some of art’s biggest names, and the documentary’s most interesting revelations are around Jeff Koons. Koons is perhaps our generation’s most commercially successful artist and, like Robert Scull, has a knack for self-promotion.

Koons even celebrates the commodification of art. In the documentary’s most fascinating scene, Koons proudly shows off his studio, in which dozens of employees are hard at work on “Jeff Koons” pieces. Koons himself often doesn’t even touch the art, instead relying on his factory of workers. This begs the question: Is a Jeff Koons piece even a Jeff Koons piece if Koons himself doesn’t create it?

Earlier in The Price of Everything, an auctioneer makes the point that great art must be greatly valued (aka expensive) because this is our culture’s way of protecting it. Money, he argues, is a necessary evil to protect the importance of art throughout history. The documentary—and the scenes with Jeff Koons in particular—provoke more hard-hitting questions:

What is art?

Why do we, as a species, care about art?

What makes a work of art valuable?

The documentary gets its name from an Oscar Wilde quote: “There are a lot of people who know the price of everything and the value of nothing.” As art and creativity explode in the digital world, some of the most interesting questions become: what has value, and why does something have value? In our age of multi-million-dollar JPEGs, these questions are even more pressing and fascinating. My partner Danny, who has a long history of investing in the creator world, has pushed my thinking on this lately. Should creators care about money? Is art still art when it’s made with a financial motive? As more people create online, the interplay between creativity and commerce may be one of the defining relationships of our time.

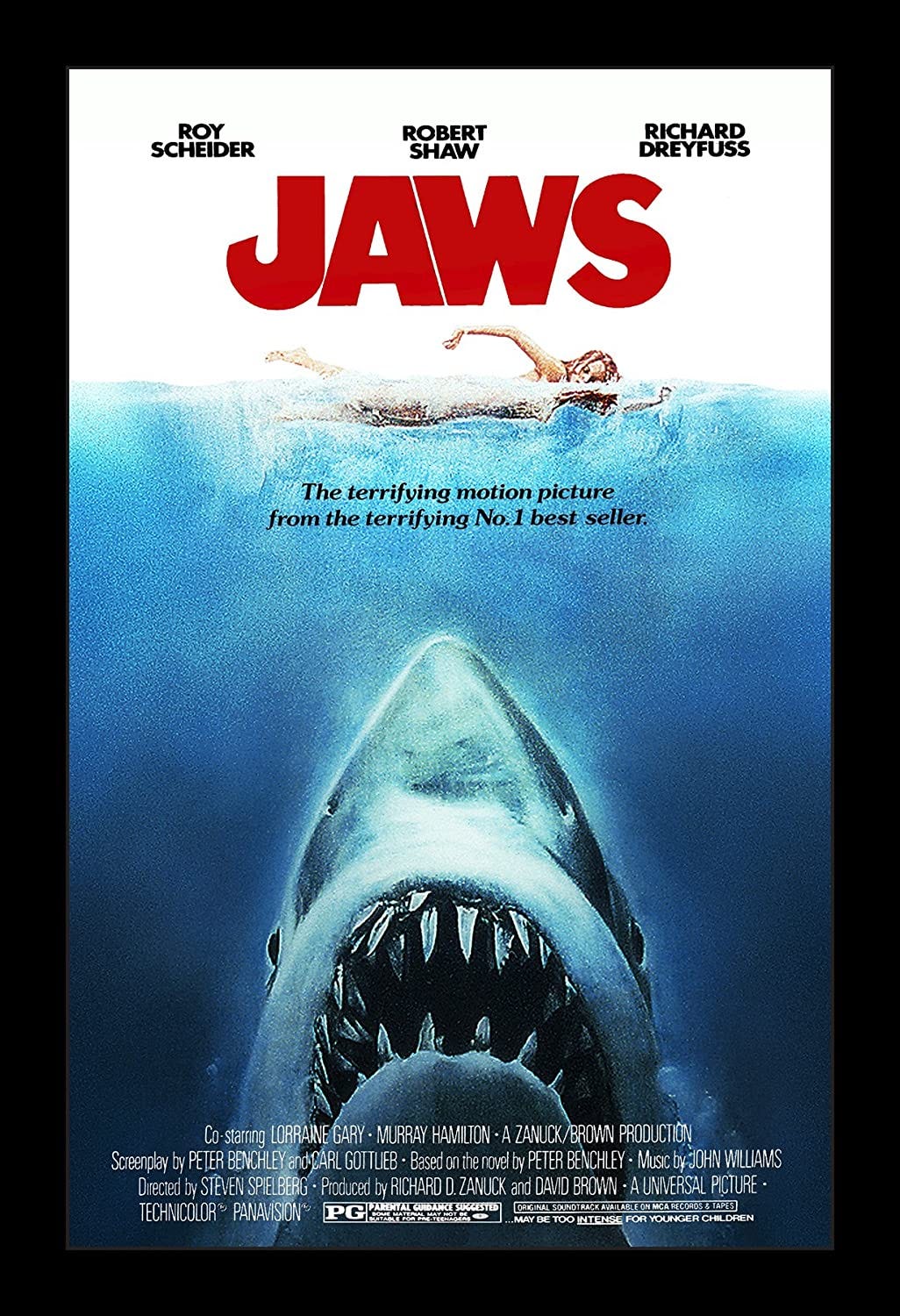

Of course, lines have been blurring for some time. Two years after the Scull sale, Steven Spielberg’s Jaws created the concept of the summer blockbuster. All of a sudden, box office grosses became a key metric (perhaps the key metric) marking a film’s success. The music world began to obsessively track the Billboard charts—and, more recently, Spotify streams. Even in the comparatively staid world of books, phenomena like Harry Potter gave us “midnight releases” and bold-print headlines announcing first-week sales.

Over the last 50 years, American culture turned to mass production—just as Henry Ford reinvented manufacturing with the assembly line, cultural centers like Hollywood and Fifth Avenue began to similarly churn out cultural products. And, of course, since the Scull sale, the fine art market has exploded. Eight-figure sales are almost routine; nine-figure sales are becoming less and less rare.

According to Masterworks, contemporary art prices have outpaced S&P 500 returns by 174% from 1995 through 2020, and beaten gold and real estate returns by nearly 2x.

Masterworks is a startup that lets anyone invest in art: if you can’t afford the $20 million Warhol, you can buy a fraction of it as an investment.

This embodies a broader trend, one I’ve written about before: the financialization of everything. Everyone is becoming an investor. With Royal, you can invest in a song. With Rally, you can invest in a person. With Sound, you can invest in an up-and-coming artist. Art is both more accessible—to use the tech buzzword, “democratized”—and also more financialized.

Royal, Rally, and Sound are all web3 companies. A Masterworks analog for web3 might be Fractional, which lets you buy a fraction of an NFT. You can be a part-owner of a Punk or an Ape. You can own a piece of the NFT of the original Doge meme, at an implied valuation of $54.5 million:

Digital art was the use case that propelled last winter’s NFT boom. But I often find digital art a difficult use case to use when explaining NFTs. Art is, after all, deeply subjective. Sometimes the answer to “Why is ___ worth so much money?” is simply, “Because someone was willing to pay that much for it.” The same concept can be applied to an NFT.

Yet the digitization of art has other interesting effects for how works are valued and how artists get paid.

During the Scull sale, Scull received backlash for not letting artists partake in his wealth creation. Artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Andy Warhol all had pieces sell in the Scull sale—yet none of them saw a penny.

Rauschenberg, for instance, had previously sold his piece Thaw to Scull for $900. In the Scull sale, Scull resold it for $85,000. Rauschenberg famously confronted Scull, angry he didn’t earn a share of the resale. This sparked a debate over whether artists should earn royalties on sales of their work, and a year later, the art historian Robert Hughes proposed a federally-legislated artists’ resale royalties program, writing: “The hitch in an informal royalty system is simple: anyone who thinks a collector will voluntarily give a 15% cut on resale back to the artist simply does not know collectors. If there are to be any royalty assurances, then, they can only work if they are written into U.S. law.” And yet, half a century later, laws are unchanged and artists still earn $0 on secondary sales of their work.

Technology is changing this. In most NFT projects, creators earn a portion of all resales. Here’s a screenshot from OpenSea after I sold an NFT last week:

My secondary sale contributed 5% of the sale price back to the original creator.

This is a powerful concept. Say Pablo Picasso, as an unknown artist, sells a piece for just $100. All of Picasso’s blood, sweat, and tears poured into later works contribute to his renown as an artist and to the worth of his oeuvre. That $100 piece might be resold for $100,000,000—and yet Picasso sees $0 from that sale. In a digital world, Picasso captures $5,000,000 from that resale, and again 5% of every resale after that. He shares in the appreciation of his work that he helps create.

In the analog world, we’ve also seen goods become more valuable based on previous owners. When Paul McCartney bought a number of Magritte paintings, their prices shot up. Nelson Rockefeller’s Rothko sold for $100 million—in part because it had been owned by Rockefeller. But it’s always been difficult and error-prone to track ownership. Blockchain solves this problem by delivering a proven, immutable history of ownership. Your NFT will be worth a lot more if Oprah or Obama used to own it. Age-old concepts of art—and of what has value—are being modernized for a digital era.

In addition to being impacted by technological shifts, creative industries are confronting cultural shifts around what it means to create for a living.

In 2014, A.O. Scott explored how society’s conception of the “starving artist” conjures an image simultaneously romantic and pathetic—a person too pure, too impractical, to make it in the world. But when that person decides not to starve, he or she becomes a sellout. And yet, Scott argues, money has become the most important measure of artistic accomplishment. In 2022, I’d extend that statement to include metrics like followers, likes, and subscribers (which, of course, are closely related to and correlated with money). Scott dryly sums up how our culture interweaves art and money: “To be a mainstream rapper is to have sold a lot of recordings on which you boast about how much money you have made selling your recordings.”

He also points out that advertising is America’s singe largest category of artistic creation. No fact better captures the overlap between creativity and capitalism. Over recent decades, “traditional” art forms and advertising have converged. In 1992, Coca-Cola made waves by hiring Creative Artists Agency (CAA) to create Coke ads. Michael Ovitz, CAA’s co-founder, masterminded the operation. (Check out Ovitz’s book Who Is Michael Ovitz? It’s excellent.) Ovitz hired top Hollywood directors like Ridley Scott to direct TV commercials—something unheard of at the time. All of a sudden, America’s greatest filmmakers were making soda ads.

Oh, and Ovitz and CAA also came up with the famous Polar Bears for Coke.

This invites interesting questions: Are those filmmakers still creating art when they film a commercial? Is a blockbuster movie art in the same way that an indie Oscar contender is? More fundamentally, is a vehicle that’s intended for profit generation still a work of art?

In a capitalist society, can you ever fully separate pecuniary motives from…anything?

A related topic is the relationship between art and content. On the internet, everyone is becoming a content creator—but at what point does content become art? Views on the distinction here may vary, but some parameters can probably be agreed upon: a musician who uploads a song to Soundcloud has created art; a TikToker who posts a video is creating content. But the lines will blur as more people create high-quality content with powerful creation tools.

Last fall, I wrote about Unity’s acquisition of Weta. Weta is the force behind some of the most jaw-dropping special effects of the last 20 years: Gollum in Lord of the Rings; the planet Pandora in Avatar; Caesar in Planet of the Apes.

Speaking to Ben Thompson, Unity CEO John Riccitiello shared his vision for allowing everyone to create stunning content with accessible tools:

Imagine in the future there’s some social platform that’s got as many residents as say an Instagram or TikTok does today, but you could create 15 seconds of what you saw in Lord of the Rings or what you saw on Avatar. You could do it at home and it’s simple and it’s powerful. I don’t think all the tools in the world are going to make anybody a great director any more so than paints will make you Rembrandt or pick your artist that you happen to like. But I do think that there is a huge number of people in the world that what gets between them and their ability to create is their facility with these types of tools and we can solve a problem. I just think we’re going to unlock creativity on a staggering scale.

What I’m in love with is what we are building towards a future where I think we could invite another a hundred million people, if not a billion people, to 21st century economies doing exactly what we find the most interesting. Which are, enabling artists to create, enabling developers to create, creating networks that provide economics that allow people to survive and thrive. Those are the social goods.

One of the biggest and most rewarding moments of my life is when a young, or not always young, but a fledgling developer will come up and say, “You made it possible for me to be a creator.”

Riccitiello’s vision of the future excites me. It’s already stunning what content can be made with just the TikTok or CapCut apps. The idea of everyone being able to create Lord of the Rings-quality productions is mind-bending. But Riccitiello is also right in that tools alone won’t make you a great director, just as paint alone won’t make you the next Rembrandt. Better tools will only raise the bar for what we see as great art or content, with the best creators always innovating ahead of the curve.

We’re at an interesting moment in time:

Better and more accessible tools are making it easier for more people to create.

At the same time, the internet is unlocking distribution for more creators to be discovered.

This leads to a digital Renaissance—a surge of creative output not seen in 500 years.

At the same time, the digitization of art (and of our world writ large) is leading everything to become financialized. Everything is now investable and monetizable. This sounds dystopian—and art purists may recoil—but it also makes earning a living more viable for creative people.

By unlocking monetization—by solving the “starving artist” problem—we can reorient the relationship between art and money.

The paradox is that the best way to protect artistic integrity is to create new paths to money-making for creative people. Recent innovations like NFTs and social tokens are new tools in the arsenal of a creator. When earning a living becomes easier, creative people are freed to focus more on their creative output and to make the things that they want to make. It’s a lot easier to create great art when you’re not worried about putting food on the table.

What’s also interesting is how our understanding of art as a profession needs to change. Our culture around art has always been contradictory: kids are told to follow their passions, encouraged to take paint classes and to play in the band and to be in a dance recital. But then kids grow up, and they’re warned away from creative careers. The starving artist trope haunts them, with parents gently (or not-so-gently) nudging their kids away from that art major and towards that business degree.

But now, the possibility of being an artist (or, if you prefer, creator) increasingly means that you don’t have to starve. Business models are changing; the architecture of creative industries is being rebuilt. Some questions are new questions: how do we separate content from art, and does that delineation even make sense any more? Other questions are old questions, and will be as unanswerable as they’ve always been: why is that good (physical or digital) worth so much damn money?

The cynic’s view is that financializing art will destroy artistic integrity—and there’s probably some truth to that. We should think long and hard about how to protect creative work. But there is also the optimistic view: that new ways of earning a living by unleashing your creativity will make creative careers more viable and attractive, crowding in talent and making money less of a concern in the first place.

Sources & Additional Reading

Thank you to my friend Cleo Abram for pushing my thinking here—check out her YouTube channel here, which will include an upcoming video on why NFTs have value

The Price of Everything | Nathaniel Kahn, HBO

Three Ways the 1973 Scull Sale Changed the Art Market | Artsy

The Paradox of Art as Work | A.O. Scott

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: