This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Hey Everyone 👋 ,

The past few weeks of Digital Native have been more specific, touching on companies innovating in commerce 👚 (The Transformation of Commerce), in socially-impactful sectors 🌱 (The Glass-Half-Full View of Technology), and in media 🎥 (Innovation in Media).

This week’s piece is more philosophical, stepping back to reflect on a broader trend rather than honing in on any particular startups. It aims to answer the questions: how did the internet kill mainstream culture, and what are the consequences?

Let’s jump in…

The Internet Killed Mainstream Culture

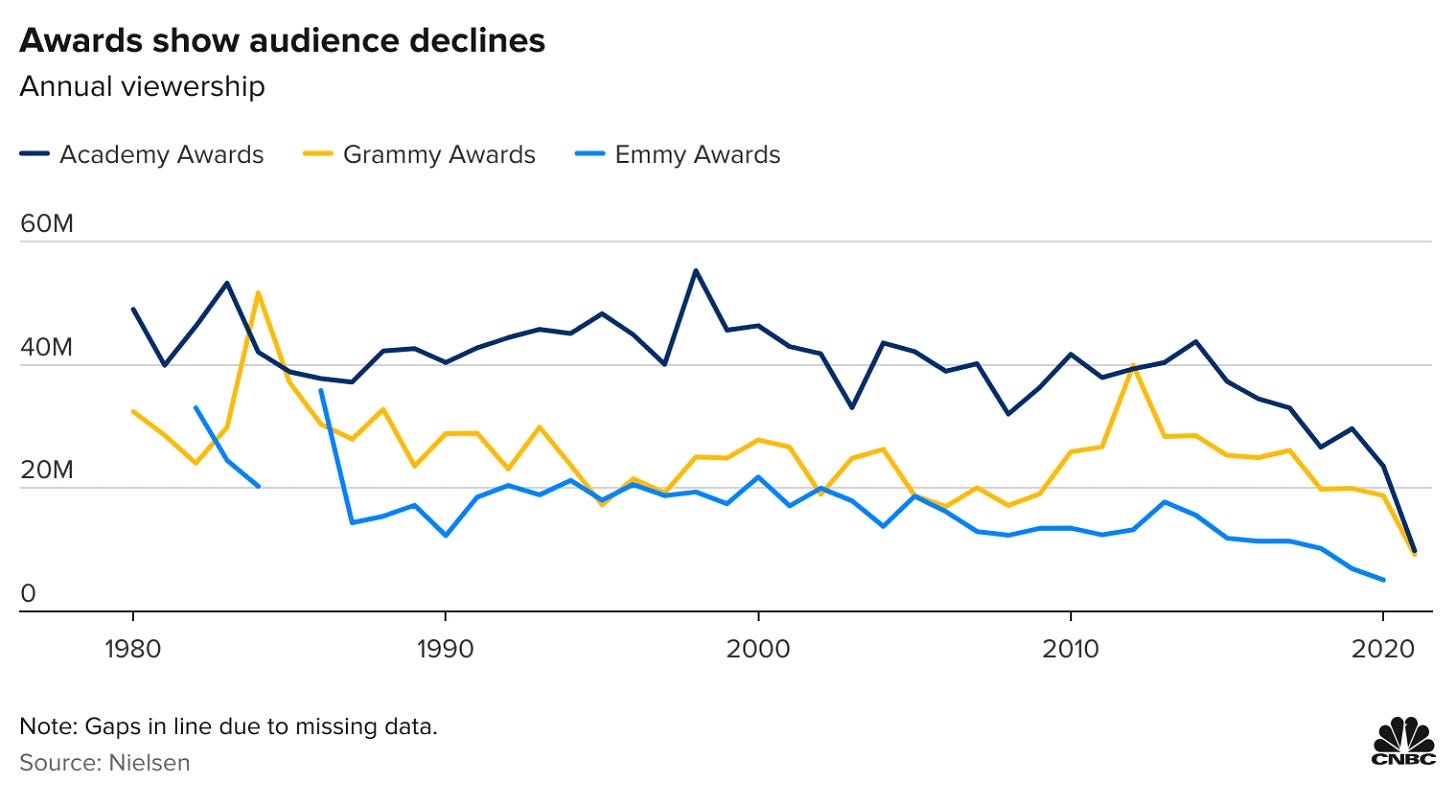

One interesting trend over the past half-century has been the decline in awards show viewership. This decline has accelerated over the past decade:

For the past hundred years, movies, TV, and music have formed our cultural lingua franca. Awards shows were their pinnacle—a reliable water cooler topic for Monday morning at the office. But that’s been rapidly changing.

The main reason: mainstream culture is dying.

Internet culture is now culture writ large, and internet culture is definitionally non-mainstream. Internet culture is messy and chaotic and fragmented. Internet culture movies at a torrid clip, and thumbs its nose at content catered to the cultural common denominator.

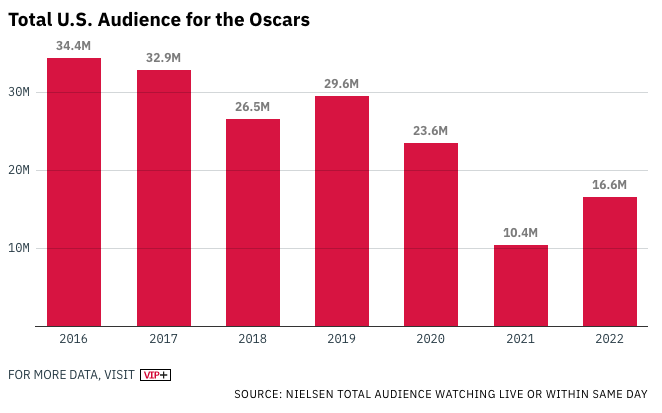

The three shows in the chart above—the Oscars, the Emmys, and the Grammys—provide a good framework for how mainstream culture is breaking down. Let’s start with the Oscars. Viewership of the Oscars is down more than 80% since its peak. It’s not all linear—this year, viewership was actually up 58% over last year:

But that stat is misleading: this year’s Oscars still had the 2nd-worst viewership in history. Of course, Will Smith’s slap made headlines—but most people found out about it on Twitter, on Facebook, or on Instagram. Then they looked up the clip on YouTube or TikTok. Few people actually saw it live.

Part of the public’s waning interest in the Oscars stems from the type of movies that the Academy is choosing to reward.

Once upon a time, box office hits could also be Oscar winners. In 1994, Forrest Gump was the year’s 2nd-highest-grossing film, just edged out by The Lion King. The film won six Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Actor for Tom Hanks. Three years later, Titanic smashed records to become the then-highest-grossing film of all-time, topping the box office for 15 weeks. Titanic set another record at the Oscars, winning 11 statues to tie it with Ben Hur for most-ever (its 14 nominations were also a record). A record 57 million people tuned in to watch Titanic clean up on Oscar night.

And in 2003, the year’s highest-grossing movie, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, tied Titanic’s record 11 wins. That year was the last time—19 years ago—that the box office champ also took home Best Picture.

In the last 20 years, the Academy has shown a preference for lesser-seen independent films with a much smaller cultural footprint. The Artist, The Shape of Water, Nomadland. (Serious question: has anyone talked about The Artist since 2012?) This year, I was struck by how few people I know had seen CODA or The Power of the Dog. As Bloomberg’s Lucas Shaw pointed out, on Oscar weekend, The Power of the Dog sat at just #9 on Netflix, one slot below a random movie called Faster from 2010.

It’s difficult to parse out how much of the Oscars decline stems from the Academy’s decision to reward indie films, and how much stems from our own societal tastes shifting. It’s a nuanced topic. Dennis Hopper framed it well:

But a major part of the show’s decline is that people tune in to award shows when the things they’ve consumed are nominated—and outside of superhero movies, there are few major cultural sensations anymore. There’s so much content online that “going to the movies” is a dying event. We’re all watching different stuff.

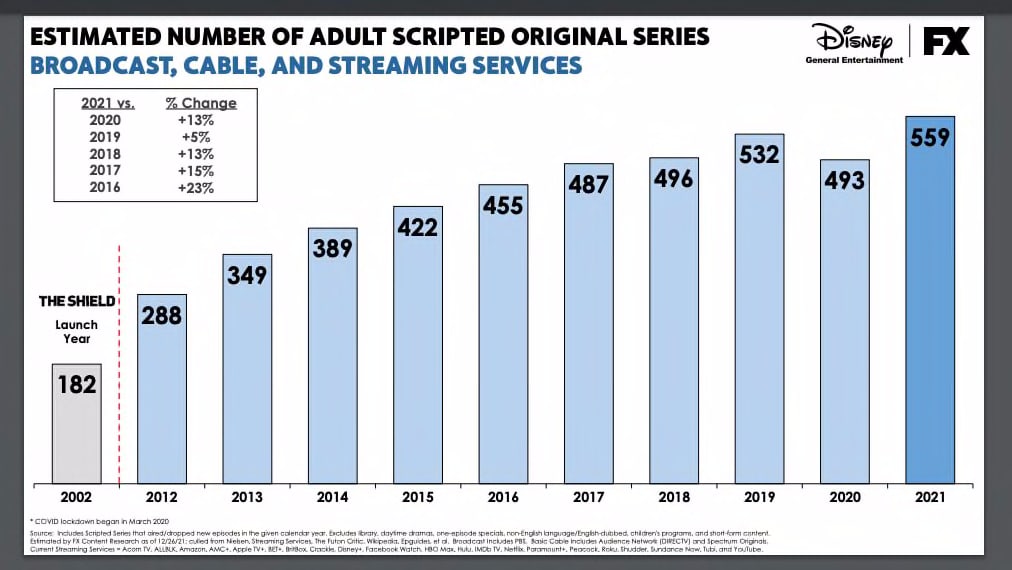

This brings us to TV (the Emmys) and to the rise of streaming. Last week I shared this chart of TV production:

In the midst of the streaming wars, we’re inundated with content. 2021’s 559 shows is the highest in history. A half-century ago, there were three TV channels and half of America watched M*A*S*H every week. Today, you’re unlikely to be watching the same show as your neighbor or coworker or barber.

The streaming release format (popularized by Netflix) further dilutes cultural impact.

An interesting case study is to compare Netflix’s Stranger Things with HBO’s Game of Thrones. Both shows were massive hits and both were viewed by roughly the same number of households. But Game of Thrones’s cultural impact was orders of magnitude larger. This came down to release strategy. Netflix dropped the entire Stranger Things season the week of the Fourth of July; by mid-July, the cultural conversation had moved on. In contrast, by releasing one episode of Thrones each week, HBO kept its show in the cultural water cooler for three months. Game of Thrones was appointment television: everyone was at the same place, at the same time, week after week. (Side note: probably for this reason, Netflix has decided to split Stranger Things Season 4 into two releases, one in May and the other in July, a strategy it just tried with Ozark.)

Mainstream television culture has been killed by 1) the sheer breadth of content, and 2) the rapid pace of streaming releases.

Finally, let’s turn to music (the Grammys). Music is also fragmenting. There are 60,000 songs uploaded to Spotify every day—about 22 million a year. We’re all discovering and listening to more and more artists. Spotify hasn’t refreshed this data since 2017, but the average number of artists that a listener streams per week has steadily ticked up:

My “Spotify Wrapped” told me that in 2021, I listened to 764 (!) distinct artists.

There’s a beauty to this: creation has never been easier, and we can all find music more tailored to our own personal tastes. But there’s also a downside: we lose a common language. I went to see Dua Lipa in concert last weekend. Dua Lipa is the most-streamed female artist in the world right now, with 70 million Spotify streams last month. “Levitating” topped Billboard’s year-end charts for 2021 as the year’s biggest song, and just broke the record for longest-charting song by a woman in Hot 100 history. Dua Lipa has 81.5 million Instagram followers. And yet, a handful of my colleagues had never even heard of Dua Lipa. (Yes, I was as aghast as you.)

The Oscars, Emmys, and Grammys are nothing if not vehicles for the stars who power the engine of pop culture. But the ubiquity of those stars is waning.

Two years ago, I wrote in The Business of Fame that we would never again have a celebrity on the scale of Marilyn Monroe or Oprah: celebrities of those eras existed before the noise of the internet, and fame is simply too accessible now. We’re all in our own content bubbles, and celebrity means different things to different people. To someone who watches Grey’s Anatomy, spotting Ellen Pompeo at a restaurant might be the highlight of your day (or year); to a non-viewer, it’s at best mildly cool. If you’re a fan of Dua Lipa, meeting her would be incredible; if you don’t know who she is, 🤷♂️. And a teenager might be thrilled to meet Emma Chamberlain, but their parent might not even know who Emma Chamberlain is.

The pandemic accelerated our culture’s fragmentation: we all became more of a digital species, meaning we retreated into our own cultural silos. In my last piece of 2020, titled We’re All Social Distancing Online, I wrote:

I’ve been thinking about 2020 as a year in technology, and I’ve been struck by its similarities to our socially-distanced physical world. When we remember 2020, we’ll remember it as the year that we also became secluded and isolated online.

That excerpt emphasizes the negativity of this shift, and I paired it with this rather alarmist image:

But the breakdown of mainstream culture isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

First, this is a trend that’s been in the works for a long time. Back in 2014, Balaji Srinivasin wrote:

An infinity of subcultures outside the mainstream now blossoms on the Internet—vegans, body modifiers, CrossFitters, Wiccans, DIYers, Pinners, and support groups of all forms. Millions of people are finding their true peers in the cloud, a remedy for the isolation imposed by the anonymous apartment complex or the remote rural location.

Re-reading Balaji’s piece, I’m reminded of Discord’s 19 million (!) weekly active servers, +184% from 6.7 million a year ago. Each server is the living, breathing nucleus of a community (including CrossFitters, DIYers, Pinners, etc). And I’m reminded of how Jack Conte of Patreon once framed online community: you may think your interests are niche—maybe only 1 in 1,000 people like the same things as you—but with 4 billion people online, that’s 4 million people who share your interests. On the internet, no niche is too niche.

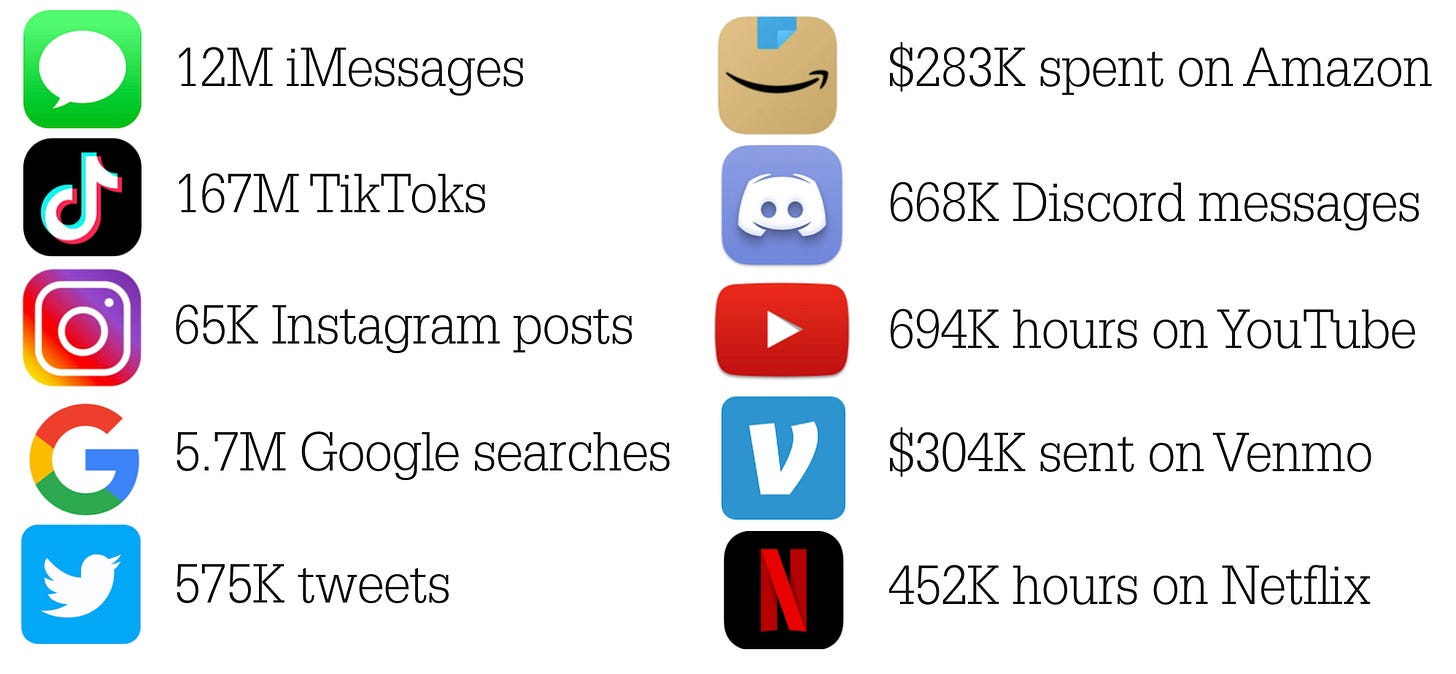

In the eight years since Balaji wrote those words, the internet has exploded. I always think back to “an internet minute”—everything that happens in 60 seconds online:

And newer content forms continue to expand and reinvent an internet minute. TikTok’s engagement, for instance, is now 3x that of Instagram.

A year ago, hardly anyone knew what an NFT was. Now, OpenSea has more NFTs listed on its platform than there were websites on the internet in 2010 (!).

Interestingly, the breakdown of mainstream culture shares its roots with much of the web3 movement: it’s a reaction to centralized authority. For the past century, a handful of studio executives, talent agents, and music producers—mostly in LA and New York—controlled American culture. Now, it’s anyone’s game. There are no rules. This is the same “down with the gatekeepers” attitude powering other major trends, like the rise of self-employment and the Great Resignation.

The breakdown of mainstream culture clearly has both good and bad aspects.

The fact that internet is vast, uncharted territory—anyone can take a hold and move culture—means that culture is becoming more diverse. Awards shows, meanwhile, remain stuck in the mostly-white, mostly-male media world of old. (See: #OscarsSoWhite, Adele’s 25 beating Beyonce’s Lemonade, or The Weeknd’s boycott of the Grammys.) The diversity of modern culture is unequivocally a good thing. But that comes at the cost of more fragmentation, the loss of a cohesive cultural language. And that fragmentation can be interpreted in different ways. Maybe instead of reading The New York Times, you now read Breitbart or subscribe to a Substack: that could be celebrated as more personalized, individualistic, gatekeeper-less media; or it could mean that you’ve sequestered yourself in your own algorithmic echo chamber, exposed only to the people and ideas that reinforce your own worldview. Both can be true.

When I think of modern culture, I think of Neil Stephenson’s The Diamond Age. Stephenson is better known for his novel Snow Crash, which coined the term “metaverse.” But in The Diamond Age, Stephenson introduces the idea of phyles. In the The Diamond Age, people live in phyles—cultural groups that have largely replaced nations. Phyles share values and interests, but often not location—they are, after all, digitally-native. As Balaji puts it, “The future of technology is not really location-based apps; it is about making location completely unimportant.” That’s the power of internet culture. We’re all living in digital phyles.

We see these tribes forming online. Take the TikTok comment below—even as TikTok’s algorithm divides us up into our own niches of culture, we feel closer and more connected than ever before. After all, in history there have never been more humans just a swipe or click or like or text or comment away.

Where is culure going? Cultural phenomena will be both momentarily larger than ever before possible (again, there are 4.5 billion people online), but the pace of culture will ensure that those highs are short-lived. Take the biggest hits of the past two falls, Squid Game and The Queen’s Gambit. Both were inescapable—142 million Netflix accounts watched Squid Game in its first month, 67% of all accounts around the world. But after some Halloween costumes and a whole lot of sales of chess sets, the culture had moved on. Culture is both bigger and smaller than ever before, and it’s certainly faster-moving. There’s no such thing as a mainstream—rather, we have 4.5 billion individual universes of culture, colliding and intersecting and building on one another to redefine how we collectively think and live.

Sources & Additional Reading

We Are All Weirdos Now | Jon Evans

Software Is Reorganizing the World | Balaji Srinivasin

Curating the Internet | Alexandra Sukin

Where Hollywood and Silicon Valley Collide | Lucas Shaw

Related (and very old) Digital Native pieces:

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: