The Long Tail: The Internet and the Business of Niche

The Long Tail Investing Framework: 2005 vs. 2022

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

The Long Tail

Let’s play a game. Take a look at the two companies below and tell me which is the better business:

Company A: Company A is a content platform founded in 1997. Last year, it did $30 billion in revenue, +18% year-over-year. It has 225 million users and spent $19 billion on content in 2021.

Company B: Company B is also a content platform. It was founded in 2005. Company B also did $30 billion in revenue last year, +46% year-over-year, and has 2.6 billion users—but unlike Company A, Company B didn’t spend money making that content. Instead, users produce content for the platform.

Which is the better business model? You probably answered Company B, which crowdsources content production instead of shelling out $19 billion a year.

Company B is YouTube and Company A is Netflix. They are the two leading content platforms in the world, and both companies did about $30 billion in revenue last year. But they did so with dramatically different business models.

This isn’t a perfect exercise, of course. YouTube pays creators 55% of advertising revenue, which is effectively its cost of content. The 225 million figure for Netflix, meanwhile, is its paying subscriber count, while the 2.6 billion figure for YouTube is monthly active users. If you assume the average Netflix account is used by ~3 people, that means there are 775 million Netflix users. Still, ARPU (Average Revenue Per User) differs greatly: for YouTube, it’s about $11.50; for Netflix, it’s about $38.70.

But directionally, this exercise is helpful and interesting. The basic principle stands: Netflix pours billions into expensive content, while YouTube taps the world’s creativity. Netflix is a business built on heavy-hitters (expensive productions like Stranger Things, The Witcher, and Squid Game), while YouTube is built on volume—500 hours of video are added every minute. YouTube is built on the long tail.

The Origins of the Long Tail

The concept of the long tail was popularized by Chris Anderson in an October 2004 article in WIRED. Anderson’s opening lines read like a prophecy of YouTube, which would be founded the following year:

“Forget squeezing millions from a few megahits at the top of the charts. The future of entertainment is in the millions of niche markets at the shallow end of the bitstream.”

I’ve written in the past about another quote in WIRED, one that didn’t age quite so well. In 2005, the media mogul Barry Diller declared:

“There is not that much talent in the world. There are very few people in very few closets in very few rooms that are really talented and can’t get out.

People with talent and expertise at making entertainment products are not going to be displaced by 1,800 people coming up with their videos that they think are going to have an appeal.”

Yikes. It turned out that there was a lot of talent in the world—many people in many closets in many rooms. The same year that Barry Diller uttered those words, YouTube was born in a small room above a pizzeria in San Mateo. On April 23, 2005, the first YouTube video was posted. The video is titled “Me at the zoo” and features YouTube cofounder Jawed Karim…at the zoo. In the 18-second clip, he talks about elephants and their trunks 🐘

The concept of the long tail remains one of the best investing frameworks for internet companies. Many of the most successful technology companies in history have been built on the long tail. Google and Facebook turn to small businesses for the lion’s share of their advertising revenue. Ebay grew by tapping into a variety of niche interests and markets. Some of our most successful investments at Index have harnessed the power of niche: Etsy showed that a lot of people are interested in buying (and making) artisanal products; GOAT showed that sneakers are a deceptively large market; Discord has 19 million (!) weekly active servers.

One of the powers of the long tail is its ability to expand selection. Amazon might be the best example. As Anderson put it in 2004:

What’s really amazing about the Long Tail is the sheer size of it. Combine enough non-hits on the Long Tail and you’ve got a market bigger than the hits. Take books: The average Barnes & Noble carries 130,000 titles. Yet more than half of Amazon’s book sales come from outside its top 130,000 titles.

The same held true for movies: the average Blockbuster in 2004 carried fewer than 3,000 DVDs, but Netflix was getting 20% of its revenue from rentals outside its top 3,000 titles. And the same held in music too: Spotify, founded in 2006, built its business on expanding music to effectively infinite selection.

With the long tail, all of a sudden you could venture beyond the bestseller lists, instead discovering that little-known gem of a book with only a few dozen copies in print. But for long tail companies to succeed, they need to ensure that niche products are in stock when you need them; if you went to order that little-known gem of a book on Amazon and could never get it, your customer experience would degrade rapidly. This is why companies like Amazon have best-in-class inventory management systems.

In many ways, long tail platforms are more egalitarian than their hits-focused counterparts; in Anderson’s words in WIRED:

As egalitarian as Wal-Mart may seem, it is actually extraordinarily elitist. Wal-Mart must sell at least 100,000 copies of a CD to cover its retail overhead and make a sufficient profit; less than 1 percent of CDs do that kind of volume. What about the 60,000 people who would like to buy the latest Fountains of Wayne or Crystal Method album, or any other non-mainstream fare? They have to go somewhere else.

We’ve seen this play out on the internet. When the crowd gets to vote with dollars and eyeballs, new forms of content and commerce suddenly become popular. When more selection is available, customer preferences and interests become much more readily apparent than when tastes are curated by a handful of executives. Would K-pop be as big as it is today if tastes were still defined by radio stations? BTS dominates the charts despite getting almost no radio play.

Another facet of the long tail—paired with this greater selection—is that the long tail helps customers discover new products. Here’s a very 2004 graphic from WIRED:

Over the past two decades, “Data is the new oil” has become an oft-used refrain in tech. If you know a customer likes Britney, it becomes easier to surface similar songs from Pink and No Doubt.

Recommendations have become a massive part of the successful long-tail companies. Recommendations (and paid placement) on Amazon dictate the flows of billions of dollars spent on commerce; Netflix and YouTube algorithms shape culture; and Spotify’s recommendation-based playlists move music.

Refreshing the Framework

The two major categories for the long tail framework are content and commerce.

Let’s start with content. TikTok is the best modern extension of this framework. Building on the concept of recommendations, TikTok’s For You Page is entirely algorithmically-generated, tailor-made to the user’s tastes and preferences. And TikTok’s built-in creation tools make producing content easier, enabling the long tail to be even longer than it is on YouTube.

TikTok relies heavily on remix culture, allowing people to build on each other’s sounds and trends; this removes the friction to create that exists even with robust creation tools (“What video should I make?”) and leads to a stunning amount of creativity. My favorite example is this hilarious video:

Essentially, a man posted a video with his girlfriend and TikTok decided that the girlfriend looked…less than willing to be in the video. So, naturally, TikTok assumed she was being held hostage. Thousands of people began to duet the video to build on the premise—we see her hands tied in rope, then we see a SWAT team at the door ready to break it down, then we see a news crew outside reporting on the scene, then we see her mother crying and pleading for her daughter’s safety. It’s brilliant, and a great example of what happens when you crowdsource the entire world’s creativity.

As creation gets even easier, the long tail will continue to lengthen. Innovations like Midjourney, DALL-E, and StableDiffusion—which provide text to image AI generation—may unlock new levels of creativity and expression. This will shift content even more away from the handful of big-budget hits, and more to the long tail of creators.

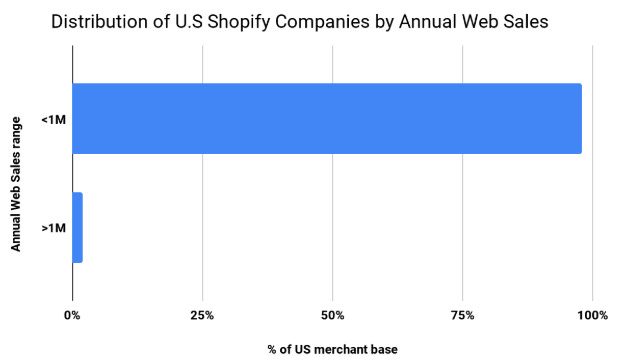

The concept of the long tail also extends to commerce. We’ve come a long way from Amazon in 2004. Take Shopify: the vast majority of Shopify merchants—about 97%—have annual sales under $1M.

And about 99% of Shopify stores have fewer than 100,000 unique visitors per month.

Shopify is built on the long tail—on serving the many, many small merchants out there that comprise the lion’s share of global retail.

The fact that Shopify is built on the long tail drives other new business models. Openstore, for instance, is a company that acquires Shopify stores in cash. As a merchant, you get a nice payday; Openstore then streamlines your operations and grows your brand. Openstore’s ultimate vision is to roll up all acquired brands into one cohesive brand.

There are dozens of Amazon roll-up companies with a similar concept (Thrasio is the largest).

We also see the long tail in businesses like Pietra that enable creators (or any marketing-savvy entrepreneur) to launch a product line. Pietra expands who can start a product line—you no longer have to be Kylie Jenner or Rihanna to start a beauty empire—thereby crowding in new business creation that otherwise wouldn’t exist.

Just as Shopify made it easier to launch an online storefront, Pietra makes it easier to launch a digitally-native product line, abstracting away the complexities of manufacturing, inventory management, and fulfillment.

Another example of a modern startup building for the long tail is Faire. Faire is a B2B marketplace that connects brands and wholesale retailers. Think of all the cute local shops you see around—those retailers need to source their products from somewhere. Merchants used to need to go to in-person trade shows, which were inefficient and expensive. Now, they can source products on Faire’s marketplace.

Faire hits on the key components of long tail businesses: Faire improves selection by giving retailers a much greater variety of potential brands to choose from, and vice versa. And Faire takes a data-driven approach to improve the experience: Faire can tell you that a similar retailer in Milwaukee had a lot of success with a sustainable candle brand, so you should give it a try too.

When you add up the long tail—the more than 1 billion videos viewed on TikTok every day; the more than 1,000,000 storefronts on Shopify; the 250,000 retailers and 30,000 brands on Faire—the long tail businesses often dwarf the businesses built only for the Goliaths.

Final Thoughts

There’s one characteristic that many of the most successful internet businesses share: they create more jobs through their platform than the company could ever directly employ. For instance, Shopify has 10,000 employees—but Shopify likely provides the foundation for 10 million jobs by enabling merchants to run and operate a storefront. (There are over 1,000,000 Shopify stores, many with multiple employees.) Or take YouTube, which employs 2,800 people. There are over 306,000 YouTube channels with over 100,000 subscribers (!), meaning there are hundreds of thousands—maybe millions—of creators making a living on YouTube.

My friend Chris Paik calls this “off-balance sheet operating leverage.” Can a company enable an entire ecosystem to form on top of it? Companies that have off-balance sheet operating leverage are often the companies that rely on the long tail.

Nearly two decades after Chris Anderson wrote that piece in WIRED—nearly 20 years after YouTube, Spotify, and Shopify came to life—the long tail framework remains one of the best frameworks through which to evaluate technology businesses. Two decades into the modern consumer internet, we’re still learning just how extensive and vibrant the long tail can be—and chances are, it will continue to surprise us.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Long Tail | Chris Anderson, WIRED (2004)

Understanding the Long Tail Theory of Media Fragmentation | Scott Baradell

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: