The Mobile Revolution vs. The AI Revolution

How AI Will Stack Up to Past Technology Revolutions

Weekly writing about how technology shapes humanity and vice versa. If you haven’t subscribed, join 50,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

The Mobile Revolution vs. The AI Revolution

The iPhone came out in June 2007; Uber was founded in March 2009.

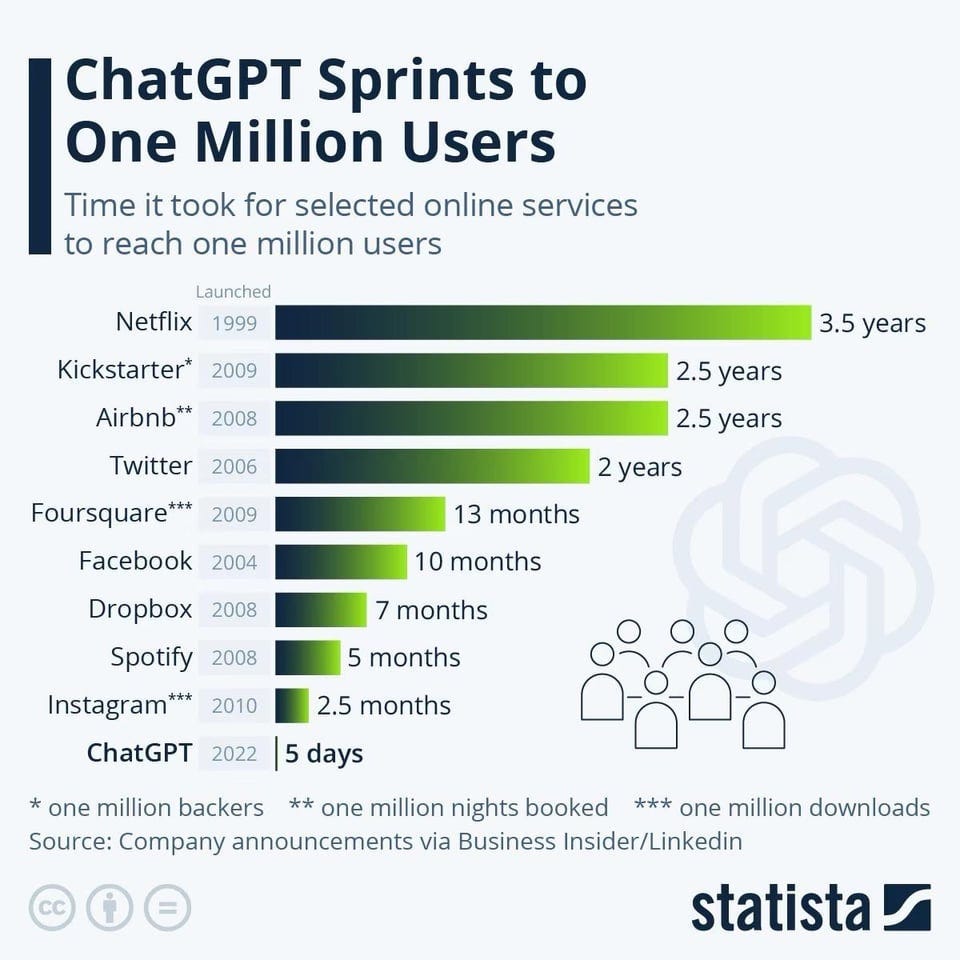

I’ve been thinking a lot about past technology revolutions and what they can teach us about our current AI revolution. If mobile offers any lesson, it’s that applications take time to develop. ChatGPT came out 10 months ago; this means we probably still have another six to 12 months before killer apps really start to emerge. And the same pattern will likely hold again when Apple launches its Vision Pro next year.

Here’s a chart of U.S. smartphone ownership after the iPhone came out—I’ve overlaid the foundings of WhatsApp (2009), Uber (2009), Instagram (2010), and Snap (2011).

Those are some of the greatest success stories in startup history: Facebook bought WhatsApp for a then-record $16B; Uber trades at a $95B market cap; Instagram would likely trade around ~$100B as a standalone company.

And where this chart ends—in March 2012—we were still early innings. At that point, smartphone penetration in the U.S. was hovering around 40%.

Here’s a chart that shows continued penetration, alongside the foundings of other major mobile companies: Tinder (2012), Robinhood (2013), TikTok (2015). These apps emerged five, six, and nine years after the iPhone launched, respectively.

The lesson here is that technology revolutions take time. Despite the hype for AI right now, we’re still early: while 58% of American adults have heard of ChatGPT, only 18% have used it. In recent months, ChatGPT monthly active users actually ticked down. I expect we’ll need more vertical-specific, user-friendly LLM applications for the technology to really break through. Many of those applications are being built or dreamt up right now.

This quest for understanding technological revolutions drove me to read Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital, an excellent book by the economist Carlota Perez (thank you to Rick Zullo for the recommendation). Perez wrote her book in 2002, shortly after the dotcom bubble burst. The book proved prescient in forecasting the 2000s and 2010s of technology, and I believe it offers some key insights for where we sit in 2023.

This week’s Digital Native explores how today’s AI revolution compares to past revolutions—from the Industrial Revolution of the 1770s to the Steel Revolution of the 1870s, the Internet Revolution of the late 90s to the Mobile Revolution circa 2010.

The key argument I’ll make is this: the AI Revolution isn’t comparable to the Mobile Revolution, as the latter was more a distribution revolution. Rather, AI is more comparable to the dawn of the internet. Or, more fundamentally, AI is an even larger-scale technology shift—it’s the dawn of a new discrete revolution that’s built not around computers acting like calculators, but computers acting like the human brain.

In short, we’re coming to a close of the “Information Age” that started in 1971, and we’re beginning a new era in technology.

Let’s dive in 👇

History’s Technology Revolutions

In the moment, it can be difficult to quantify a new technology’s impact.

This leads to predictions that don’t age well—for example, the economist Paul Krugman’s 1998 declaration, “By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet's impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.” Yikes. Poor Paul has had to live down that sentence for a quarter-century.

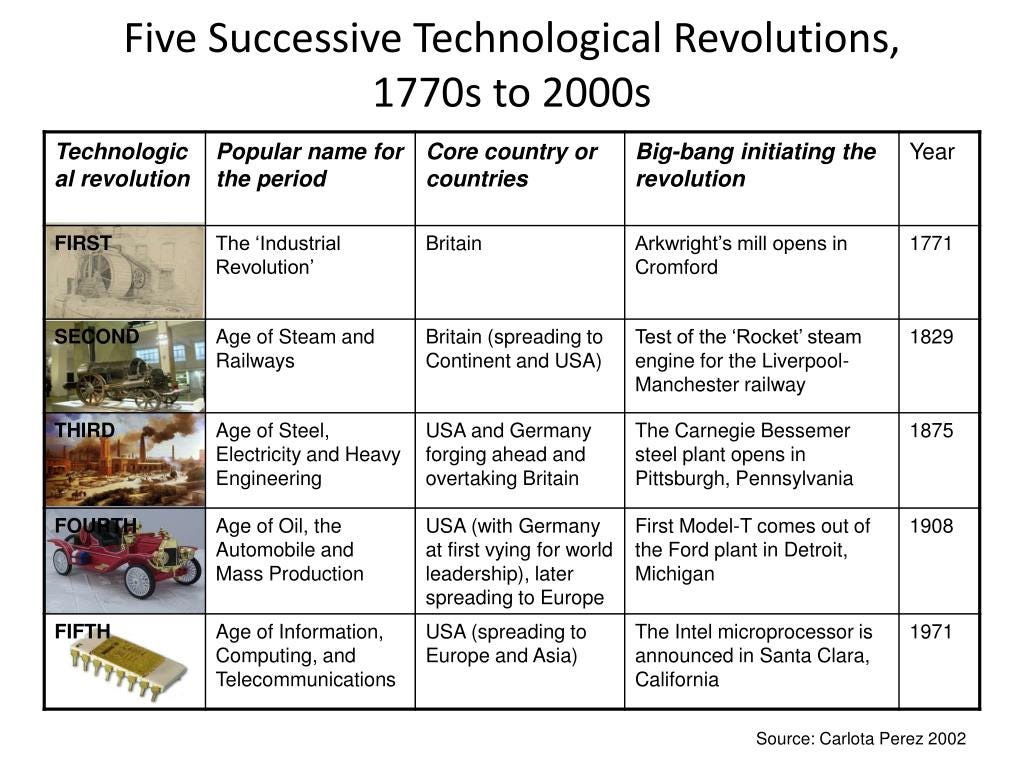

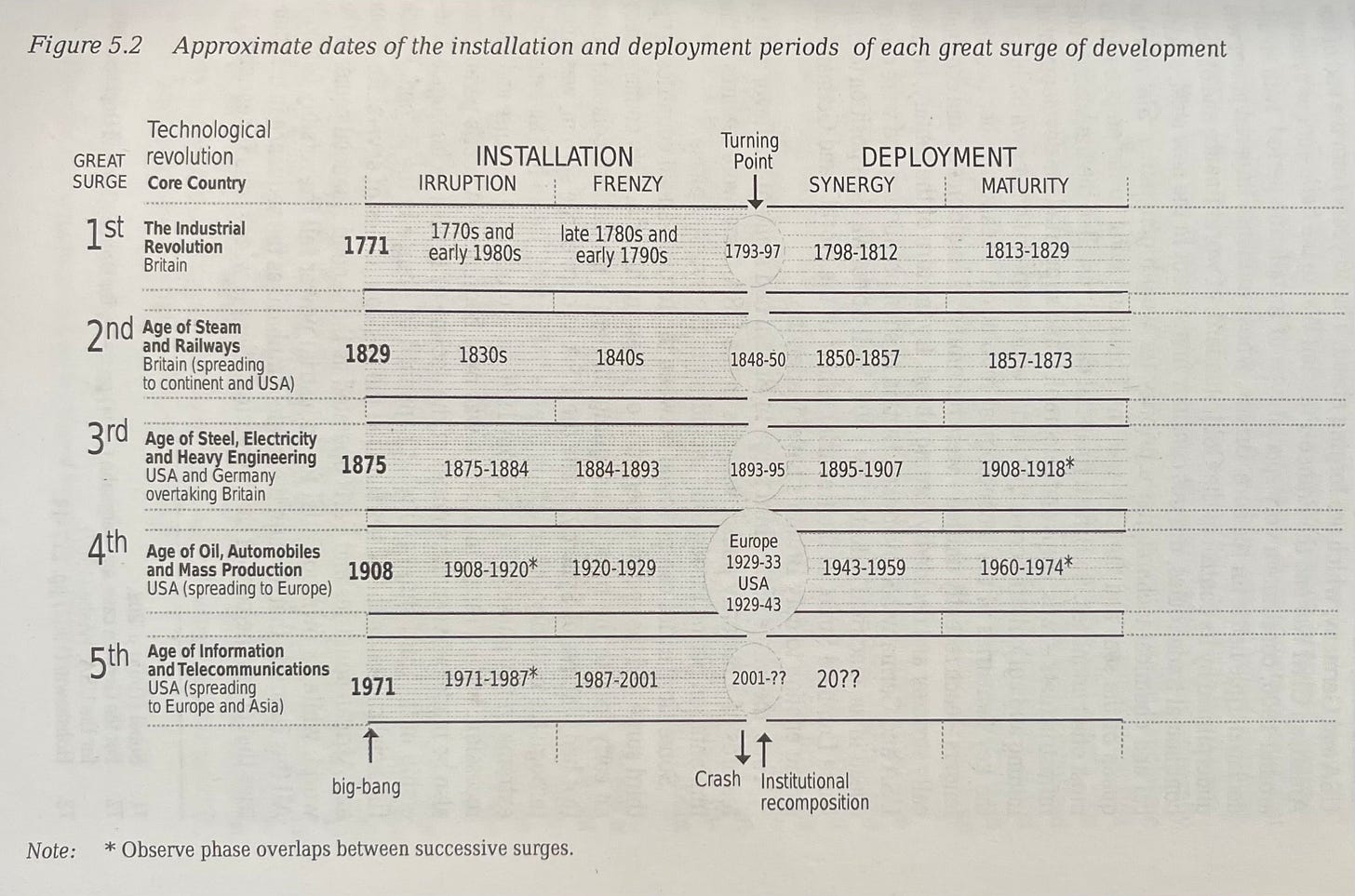

This is why it’s helpful to zoom out—to study history’s past cycles of innovation and to try to discern patterns. This is the focus of Carlota Perez’s book. Perez focuses on five distinct technological revolutions from the past ~250 years. Each revolution, she argues, was sparked by a “big bang” breakthrough:

Our most recent technology revolution, the dawn of the so-called “Information Age,” began in 1971 with Intel developing the microprocessor. Microprocessors were manufactured with silicon, giving Silicon Valley its name; the rest is history.

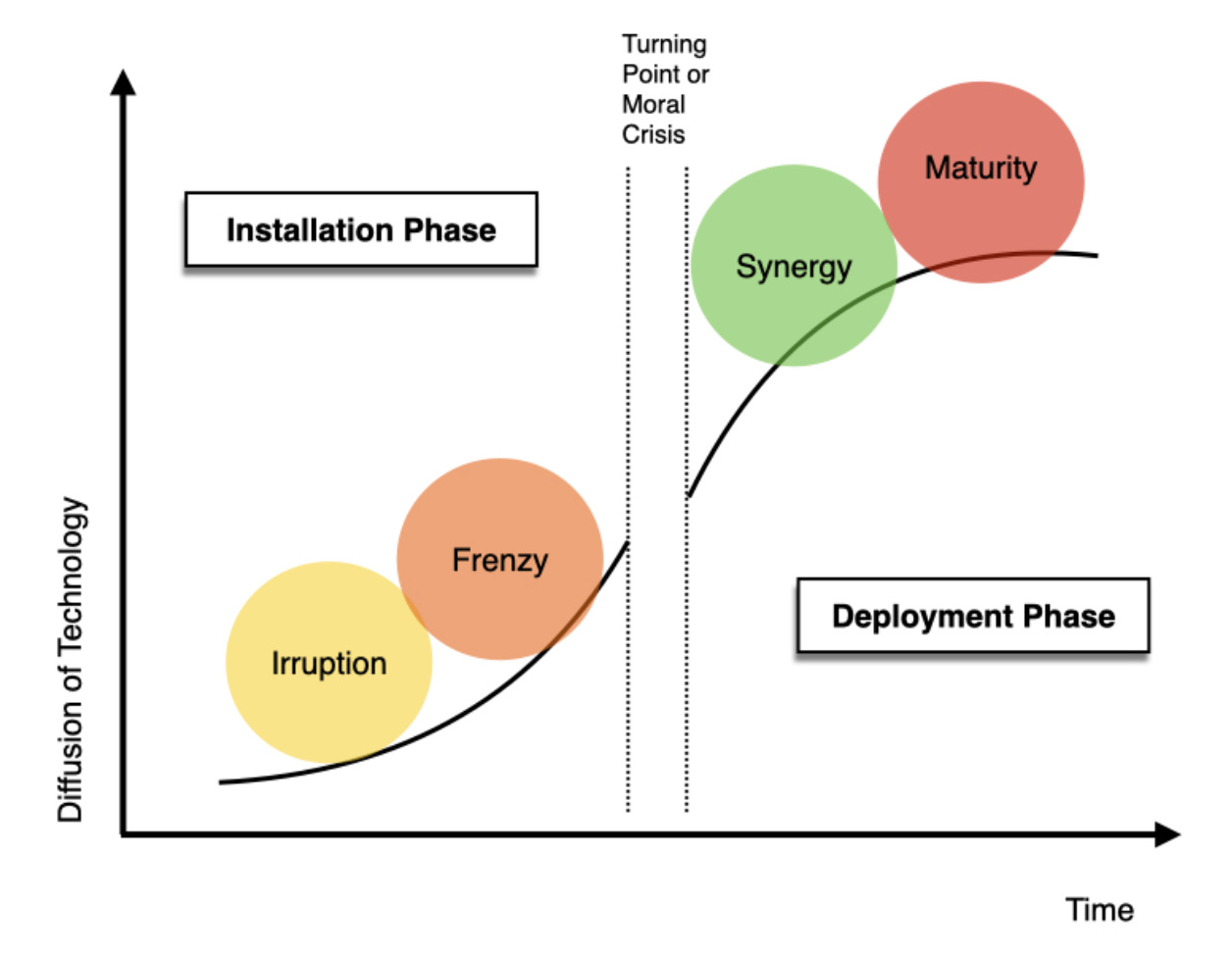

Technology revolutions follow predictable boom-and-bust cycles. An exciting new technology leads to frenzied investment in that technology; frenzied investment leads to the formation of an asset bubble; that bubble eventually bursts, cooling an overheated market. What makes Perez’s book remarkable is that she wrote it in 2002, shortly after the dotcom bubble had burst. Many people at the time were declaring the end of the internet era. But Perez argued that the bubble bursting was only the middle of a predictable cycle; the dotcom crash was rather a so-called “turning point” that would usher in the internet’s Golden Age (what she calls “Synergy”).

According to Perez, technology revolutions follow ~50-year cycles. “Turning points”—which often come in the form of a market crash—typically occur about halfway into the cycle. Many crashes bear the name of the revolution’s prevailing technology: canal mania (1790s); railway mania (1840s); the dotcom bubble (late 1990s).

After a technology’s turning point, the technology enters the deployment phase—this is ~20 years of steady growth and broad wealth creation. The internet’s widespread adoption in the 2000s and 2010s, buoyed by the arrivals of mobile and cloud, bears this out. Looking retrospectively from 2023, Perez’s framework appears spot on.

We can observe the “shift” from one technology revolution to the next in the companies that dominate an era. In the 1930s and 1940s, for instance, oil and automobile companies replaced steel companies as the largest businesses in America.

Here are the 10 largest companies in the world in 1990:

Today, of course, tech companies dominate: Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft, Nvidia, Meta. Tech domination is more pronounced via market cap, while the table above shows revenues, but the point remains. (Apple, for what it’s worth, brought in $394B in sales last year—with 25% profit margins to boot.) In the 1990s and 2000s, we saw technology begin to dominate; today, Big Tech represents 27% of the S&P 500.

But tech domination is also a sign of something else: maturation.

The Next Revolution: AI

Take another look at Perez’s chart above; the final stage is when a technology begins to mature. And that’s what we’ve been seeing with Big Tech. Companies like Alphabet and Meta have a bad case of arthritis.

Maturation extends to the private sector. I had a debate with a former colleague the other day—how many companies founded since 2016, we wondered, had hit $100M in ARR? Wiz, Ramp, Deel, Rippling. There might be a few others. But the list is short. And how many new apps reliably hover near the top of the App Store—apps not funded by Bytedance (TikTok, CapCut) or Pinduoduo (Temu)?

New revolutions emerge when the potential of the previous revolution approaches exhaustion. And it feels like we’re at the exhaustion point. Capital flowed into the venture world over the past decade, but that capital is increasingly chasing point-solutions. Abundant capital is thirsting for a new seismic, fundamental shift.

Thankfully, we have one. Enter: AI.

The arrival of AI is near-perfect timing to Perez’s framework. For AI, the “big bang” event—to use Perez’s terminology—was probably the release of ChatGPT last year.

You could argue that the big bang was actually the publication of the seminal paper Attention Is All You Need in 2017, which introduced the transformer model. But I think we’ll look back at ChatGPT as the true catalyzing moment.

Another sign of market saturation and the dawn of a new era: top talent drains from mature, slow-moving incumbents to strike out on its own. The co-author of Attention Is All You Need, Aidan Gomez, left Google to build Cohere.ai. The Google Brain researchers behind Google’s image model also left the Big Tech giant, founding Ideogram.

When you zoom out, the past 50 years have pretty closely followed Carlota Perez’s framework—in much the same pattern that we saw with the Industrial Revolution, with the steam engine, with steel, and with oil and mass production. To oversimplify:

1970s and 1980s: Irruption—venture capital is born as an industry, turbocharging the nascent Information Age

1990s: Frenzy—things get a little ahead of their skis

2000-2015ish: Synergy—the Golden Age, with mobile and cloud acting as accelerants on the fire

2015-Present: Maturation

Exogenous shocks muddy the picture. Many blamed the dotcom crash on the September 11th attacks, for instance, but that was incorrect; 9/11 worsened the market correction, yes, but the bubble had already begun to burst in spring 2001. The Great Recession and, later, COVID and related government spending also cloud the framework. Who could have predicted a mortgage crisis and a coronavirus pathogen? But when you zoom out, the pattern is there.

We’re now entering Phase One for AI—explosive growth and innovation:

This is exciting.

It means that the comparison in the title of this piece—the Mobile Revolution vs. the AI Revolution—is something of a misnomer. AI is bigger, a more fundamental shift in technology’s evolution. VR/AR, perhaps underpinned by Apple’s forthcoming Vision Pro, might be a mobile-scale revolution—a massive shift in distribution. That’s probably 5-ish years away. But AI is bigger.

The way I think about it: we’re moving from the calculator era to the brain era.

Back when computers were being created, there was a debate among experts—should the computer be designed to mimic a calculator, or to mimic the human brain? The calculator group won out (particularly because of technology’s limits) and the computer was born as we know it: literal, pragmatic, analytical. Computers are very good at….well, computation. They’re less good at nuance, reasoning, creativity.

Now, of course, that’s changing. AI is actually quite good at these things. In fact, AI is now better than humans at many uniquely-human tasks: reading comprehension, image recognition, language understanding, and so on. One study found that not only did ChatGPT outperform doctors on medical questions, but the chatbot had better bedside manner. (It turns out, ChatGPT doesn’t get as tired, irritable, or impatient as human physicians.)

Computers used to be good at math. Now they can write and draw and paint and sing. Naturally, this new technology epoch will bring with it new opportunities for innovation.

The Startup Opportunities

So what startups will a new technology revolution yield?

I’ll have (multiple) future pieces on the opportunities in AI’s application layer. This piece will only briefly touch on the topic. But I tend to think through three categories of innovation: (1) Extensions, (2) Enablements, and (3) Adjacent Industries.

Extensions

Extensions are natural carry-forward ideas from the most-recent revolution. For instance, we’ve seen a dozen “Instagram for AI” companies come out of the woodwork. Startups like Can of Soup let you use AI to create photos of you and your friends. As the company describes it: “You can create a photo of you, your best friend, and Rihanna playing volleyball on the moon, edit it to perfection, and share it to your friends feed.” In this way, generative AI provides a new atomic unit for a new social network.

Or take another concept that I think should exist—Pinterest for AI. I’m obsessed with interior design, and my newsfeeds are littered with gorgeous homes—only upon further inspection do the captions mention the images are actually AI creations. What about an AI-native Pinterest for shopping inspiration?

“Extensions” face the natural question of how they’ll beat the incumbent. Can “Canva for AI” really beat Canva, which has already moved fast to layer in AI tools? Only time will tell.

Enablements

In a few years, it will seem silly to call a company “an AI company,” just as it today seems silly to call a company “a mobile company.” Every company will incorporate AI, just as every company incorporates mobile. But there are companies that will be founded because they’re uniquely enabled by generative AI.

Enablements are the companies made possible by a new technology. Think Uber using mobile’s geolocation to offer a 10x better taxi experience (and thus expand the market size). Or think Snap, using your mobile camera to create a category around ephemeral photo-sharing. Both companies couldn’t exist before smartphones. AI will similarly underpin new AI-native companies that take advantage of what’s now possible.

Thinking through opportunities in Enablements requires a bit more creative thinking. It helps me to think through broad frameworks. One example:

The internet blew open the gates of distribution.

Generative AI blows open the gates of production.

It’s becoming faster, easier, and lower-cost to make…any digital content. What happens when technology can be creative, and when we all get creation superpowers?

Adjacent Industries

Technology revolutions have a fascinating way of underpinning large adjacent industries. The credit card industry was really an offshoot of mass consumerism made possible by the automobile; the same goes for shopping malls.

Yesterday, I bought a domain. Before the internet, who would think that a marketplace for websites like GoDaddy would be a $10B market cap business spitting off $4B in revenue? Or, even more obvious examples—Search and Social Networking are relatively “young” industries, yet Google did $282B in revenue last year, while Meta raked in $116B.

What new industries will pop up as second- and third-order derivatives of AI?

Betting on the Right Horse

One thing that’s critical: betting on the right horse.

Here’s a paragraph from a 2010 Reuters article:

The popularity contest between competing smartphone photo manipulation apps Instagram and PicPlz has been won by PicPlz in one regard today, after early Instagram investor Andreessen Horowitz said it has decided to switch teams and pour $5 million in first round funding into PicPlz.

Andreessen Horowitz had previously invested $500,000 into Instagram.

Yes, a16z had put $500K into Instagram—then decided to instead invest heavily in its competitor, PicPlz. a16z even told TechCrunch it would take a more “passive” role with Instagram as it amped up its involvement with PicPlz. We all know which horse won the race.

There will be dozens of “___ for AI” popping up in the coming years; it will be difficult to separate signal from noise. One of the challenges in the “Irruption” phase, which involves frenzied startup creation, is discerning which entrepreneurs and companies will go the distance.

Final Thoughts: Creative Destruction

The economist Joseph Schumpeter once wrote: “Capitalism is a process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.” The same is true for technology, which goes hand-in-hand with capitalism; innovation is capitalism’s spark, and technology its fuel.

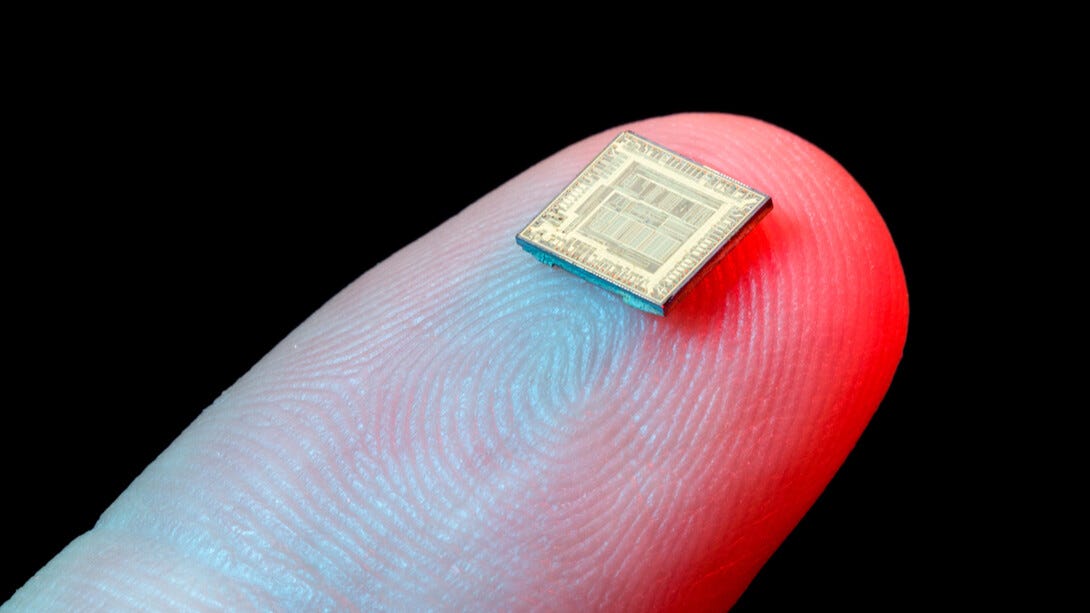

We’ve come a long way since the Information Age began. A terabyte hard drive in 1956 would’ve been the size of a 40-story building; today, it fits on your fingertip. Moore’s Law means that microchips improve exponentially.

This being said, the fact that the Information Age is in its maturation phase is tough news for growth investors. Most late-stage private companies are marked well above their “real” valuations. Public tech stocks have seen a ~70% sell-off over the past year and a half. This reckoning should naturally extend to private tech stocks. A company that raised at $10B is probably worth $3B; a company that raised at $1B is probably worth $300M.

On the flipside, it’s an excellent time to be investing at Seed. We’re at the dawn of a new era in tech—and as talent leaves Big Tech and overvalued startups, more entrepreneurs will emerge to build in this new era. This was the thesis behind Daybreak that I wrote about a few weeks back.

Amara’s Law says that we tend to overestimate the effect of a new technology in the short run and underestimate the effect of that technology in the long run. This means that AI might be a little frothy right now—it’s difficult to make the math work for a portfolio of $100M Seed valuations. If Perez’s framework holds, we’ll be in for more than one correction in the years to come. But those corrections won’t detract from the long-term potential of a new paradigm-shift in technology.

There are also open questions about where value will accrue. We’re entering this new revolution with a slew of trillion-dollar tech companies at the helm; what’s more, Big Tech has been unusually quick to respond to the threat posted by AI. Traditionally, incumbents tend to avoid radical change for fear of upsetting the apple cart—for fear of sacrificing juicy short-term profits in favor of massive self-disruption. But maybe this time is different. The question remains: will incumbents vacuum up the value, or will more agile, AI-native upstarts be able to win major segments of the market? Time will tell if Google and Meta sound as dated in 2043 as Yahoo! and AOL do in 2023.

The internet, mobile, and cloud looked like their own distinct revolutions—but rather, they may have been sub-revolutions in the broader Information Age that’s dominated the last 50 years of capitalism. We’re now seeing a brand new sea change—one that only comes around every half-century.

In other words, we’re in for a helluva ride.

Sources & Additional Reading

Carlota Perez’s book is accessible reading—you don’t need a background in finance or economics. It’s worth reading, and you can buy it here. Thanks to Rick Zullo for the recommendation.

Marc Andreeessen had a wide-ranging interview on the Huberman podcast—it’s nearly three hours (!) but covers many interesting and related topics on AI.

I enjoyed my friend Mike Mignano’s piece on what startups might form on AI’s application layer

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: