The Retail Revolution

10 Forces Shaping Commerce, From TikTok to CACs to Sustainability

Weekly writing exploring how technology and humanity collide. If you haven’t subscribed, join 40,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

Hey Everyone 👋 ,

Over the past two weeks, I wrote a two-part series on 10 forces shaping modern commerce, as well as the startups both riding and accelerating those shifts. We cover everything from TikTok to Roblox, CACs to sustainability, celebrity brands to livestreaming. This piece combines Part I and Part II into one single essay.

Let’s jump in.

The Retail Revolution 🛍

Rihanna had the most effective commercial of the Super Bowl. About halfway into her halftime set (which attracted 119M viewers—6M more than the game), she touched up her make-up with her very own Fenty products. According to Launchmetrics, the stunt garnered Fenty $5.6M in earned media value within 12 hours.

Commerce bleeds into every aspect of our lives. It’s there in the Super Bowl halftime show, sure, but it’s also the fuel powering the game: ~70 commercials, costing $7M for a 30-second spot, drive the NFL’s revenue from the game. (About 70% of Super Bowl ads are for alcohol, cars, and food.)

While commerce has been around forever, its centrality in our lives is relatively new. One of the earliest recorded forms of commerce was cattle trade around 10,000 B.C. Cattle had a fixed value and were exchanged for goods and services. As a result, the Latin word for money, pecunia, comes from pecus, which is the Latin word for cattle.

But before the Industrial Revolution, product differentiation was limited. As a result, marketing in its modern form didn’t exist. Only with the automation of manufacturing—which unlocked the floodgates of production—did it become essential to advertise products given consumers now had choice. The internet added accelerant to the fire, introducing new sales channels and the advent of digital advertising. Today, we’ve come a long way from trading cows: commerce is a $26 trillion global market, and e-commerce comprises about $6 trillion of that.

A year ago, I wrote Talking Shop: The Transformation of Commerce—a two-part deep-dive into 10 trends shaping commerce. It’s time for a refresh. This week and next, I’ll cover 10 new trends:

Power to the People

Gen Z Interns & Viral Marketing

The CAC Rules No Longer Apply

Influencer Commerce & Celebrity Brands

Self-Expression

AI 🤝 Retail

Immersive Shopping

B2B Commerce Makes Life Easier

Sustainable Commerce

Don’t Discount Discounters

Let’s dive in.

1) Power to the People

One of the challenges of online shopping is the omnipresence of dark patterns.

A “dark pattern” is a tactic used by a retailer to trick the consumer into doing something that benefits the retailer more than the consumer. Most retailers accomplish this with misleading web and app design. Examples include sneaking extra items into your cart, or using confusing language when you go to cancel an order—“Do I click ‘Cancel’ or ‘Ok’ to complete cancellation?” 🤔

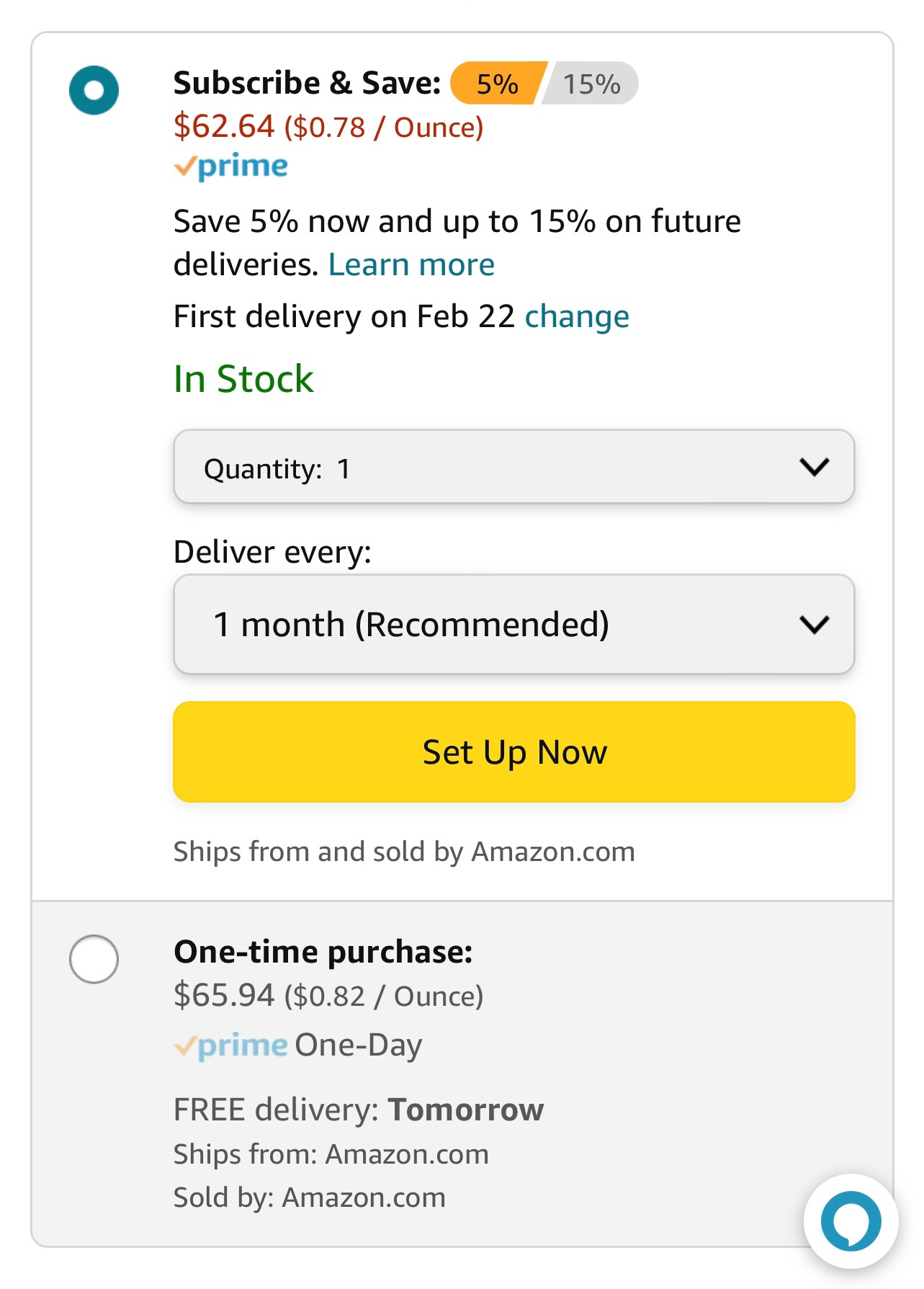

A study by Merchant Machine found that Amazon—famous for its customer obsession—is the worst culprit in retail, with 11 identified dark patterns. The most infuriating one that I consistently come across is the default to “Subscribe” to recurring purchases, versus complete a one-time purchase; here’s what it looks like when I go to order Whey protein:

Dark patterns may succeed in juicing short-term numbers, but over time they erode customer trust and tarnish a retailer’s reputation. One of my long-held beliefs about commerce—and about consumer-facing technology in general—is that power is always shifting to the customer. The arcs of technology and business bend toward customer-friendly products. This is especially true in today’s world of abundant consumer choice.

As a result, we’re seeing a shift to more products built to improve the customer experience rather than to get in the way. One example: loyalty programs. Starbucks just passed 30 million U.S. users in its rewards program, meaning that roughly 1 in 8 American adults is a member. (Fun fact: for many years, Starbucks was America’s leading mobile payments app—it now sits in second place behind Apple Pay, but still ahead of Google Pay.)

Loyalty is key to driving customer lifetime value and to making a brand’s unit economics work. Nike’s loyalty members account for 70% of sales in new stores; Prime members spend 2.3x more on Amazon; Marriott loyalty members book 50% of rooms. Companies like Yotpo let retailers build customized rewards programs, offering a flexible infrastructure layer for loyalty.

We’re also seeing a newer generation of startups build with customers in mind:

Catch, one of our portfolio companies at Index, cuts out credit card companies, letting shoppers pay by bank or debit. In return, shoppers earn 10% in store credit. As Catch puts it: “You win. Brands win. Everyone wins except the credit card companies.”

Safara, meanwhile, brings loyalty to hotels, offering a unified program across a million hotels that gives customers 10% back on every booking.

And Beam, another company we work with at Index, embeds social impact into the checkout experience. Customers can donate 1% of their cart to a cause of their choice—say, LGBTQ+ homelessness, ocean conservation, or school lunches for low-income kids. Importantly, it’s the brand giving up that 1%, not the customer. Shoppers get to shop their values, at no cost.

Catch, Safara, and Beam are all built around delivering a better experience to the consumer. Their business models work because brands also win: average order values swell, conversion rates improve, retention ticks up. Incentives are aligned.

Each is an example of a broader trend in commerce: power is shifting to the people, and the brands that win aren’t the brands that take advantage of the customer’s naivete, but the brands that deliver a more affordable, convenient, and enjoyable shopping experience.

2) Gen Z Interns & Viral Marketing

Last summer, 20-year-old Mary Clare Lacke interned at Claire’s, the teen accessories retailer that was once the go-to place for any 90s-baby looking to get her ears pierced. Claire’s revenue declined throughout the 2010s as the brand struggled to stay relevant in the digital age. One of Lacke’s tasks as an intern: inject fresh energy by running Claire’s nascent TikTok account.

In an 11-second video, Lacke riffed on a TikTok trend called “krissing”—a bait-and-switch type of video, inspired by Kris Jenner, that misleads the viewer and then reveals the fake-out. Lacke used #krissing to reveal that Claire’s did indeed still sell gummy bear earrings. The video generated 1.5 million views and 20,000 new followers for the company’s TikTok account.

This story speaks to a new phenomenon: the rise of the Gen Z TikTok intern.

Mary Claire Lacke is now one of four TikTok “college creators” that work for Claire’s as interns during the school year, producing new TikTok videos each week. Other brands are following suit, leveraging young people’s digital fluency to stay relevant.

The payoffs can be immense: while a 30-second Super Bowl ad would have cost you $7 million, the 11-second Claire’s video reached millions (with much better targeting to boot), and likely cost just a few hours of hourly wages for a college intern.

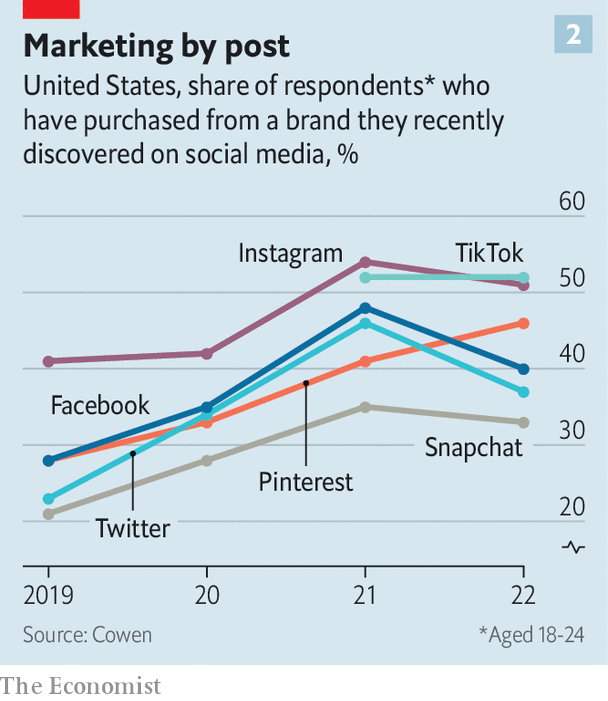

Mastering social channels is crucial in today’s world. The Economist found that 50% of consumers have bought from a brand they recently discovered on social media.

A recent McKinsey study takes things one step further: six in 10 Americans under 25 have actually completed a purchase on a social media site. Just this week, TikTok announced plans to move forward with its Shop feature, which gives brands the chance to sell products directly on the app with a full checkout experience.

The savviest brands consistently go viral: E.l.f. Cosmetics with its “Eyes Lips Face” TikTok song; Chipotle with the Lid Flip Challenge; Wendy’s with its Twitter roasts. One of my favorite examples: the time Burger King announced it would offer 1-cent Whoppers to any smartphone user within 600 feet of a McDonald’s. Within a week, the campaign drove over 1M downloads of the Burger King app, and the app went from #400 to #1 on the App Store.

In last year’s Revisiting Lifetime Value and Customer Acquisition Cost, I wrote about some examples from Calm, one of the savviest marketers out there—sponsoring the anxiety-ridden 2020 Presidential Election coverage on CNN, for example, or covering Naomi Osaka’s fine for withdrawing from the French Open for her mental health. My favorite: Baa Baa Land (a riff on La La Land), an 8-hour film of sheep grazing in a field. The company marketed it as “the dullest movie ever” and promised it as the ultimate insomnia cure.

Some companies even build virality into their features: Spotify Wrapped is a masterclass in viral marketing (in 2021, 60M users shared their Wrapped), while TikTok’s watermark and easy export features powered its ascent.

Figuring out how to go viral and how to generate earned media value—even if it requires hiring a Gen Z intern—is vital to survival as a brand in 2023. There’s more “noise” out there than ever before, and staying top-of-mind for consumers is a constant challenge. This is particularly true given what’s happening with customer acquisition costs.

3) The CAC Rules No Longer Apply

Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) changes have created something of a recession in digital advertising. The major ad platforms—Google, YouTube, Snap, Meta, etc.—are seeing slowing or even negative ad revenue growth. Digital real estate was finite to begin with, and supply-demand imbalances made sure that ad prices were steadily creeping up throughout the 2010s. Now, it’s harder than ever to measure those ads or ensure ROI. The old adage goes, “Half my advertising spend is wasted; the trouble is, I don’t know which half.” In a post-ATT world, this takes on new meaning.

I covered ATT in more detail in last year’s CAC: Customer Acquisition Chaos, and one of the best recent pieces breaking it down is Eric Seufert’s ATT Recession. The deterioration of direct response advertising may be the biggest shift in retail right now, as every brand faces CAC headwinds. Some enterprising startups are lessening the hurt. Northbeam and Triple Whale, for instance, are ad attribution platforms that help media buyers understand how their ad spend is performing—something that’s much more difficult in 2023 than in recent years.

We’re also seeing creative new channels emerge. Earlier this month, we announced our investment in Flagship, which lets creators launch their own boutique storefronts that showcase their favorite products. Brands are drawn to Flagship because they pay $0 unless someone converts; when someone buys, they’re happy to give up a percent of the sale because they just acquired a new customer. Flagship boutiques are a new, scalable channel for brands to explore.

Another example of a new acquisition channel: short-term rentals. Minoan is a startup that lets property managers buy brands for their rental units, where hundreds or thousands of annual visitors will experience the product—say, a Casper mattress, a Fellow coffee grinder, or a West Elm accent chair. Brands clamor to offer property managers discounted goods, because they want to be front-and-center for prospective new customers. In a world with more digital nomads, short-term rentals could become the newest form of experiential retail.

As CACs steadily creep up, brands have to get more creative about how to refine and measure their ad spend, and about how to reach customers through new channels.

4) Influencer Commerce & Celebrity Brands

With CACs rising, brands with built-in distribution are well-positioned. In other words, celebrity brands.

I recently got into an argument with a friend about celebrity brands. Inferior celebrity products, he argued, would beat out better products by leveraging free distribution— say, a massive Instagram following. I countered that consumers are savvy, and poorly-executed celebrity brands don’t stand a chance. I stand by that.

There’s a growing graveyard of celebrity brands that failed to catch on; people can sniff out inauthenticity and low effort. Most struggling celebrity brands are silently sunsetted, with a celebrity gradually posting less and less about her brand.

Even big celebs struggle: the WSJ recently reported that Beyoncé’s partnership with Adidas, the clothing brand Ivy Park, saw its sales fall 50% last year. Adidas projected $250M in 2022 sales, but the brand only brought in $40M. Ouch. Ivy Park is now set to lose about $200M for Adidas this year. (My take is that Beyoncé’s aspirational, somewhat-aloof persona is at odds with Ivy Park’s athleisure style. She should have created an ultra-luxury brand.)

The celebrity brands that endure do three things right: 1) They’re authentic to the celebrity, 2) They have a genuinely unique insight, and 3) They move beyond the celeb figurehead. The two most successful examples, in my mind, are Rihanna’s Fenty and Kim Kardashian’s SKIMS. Their unique insights:

Fenty: Make-up should come in more shades for people of color.

SKIMS: Shapewear is outerwear.

Both are raking in hundreds of millions, if not billions in revenue. They injected new energy into stale categories.

Both brands have also elevated themselves beyond Rihanna and Kim. SKIMS marketing, for instance, now rarely features Kim herself; the company brilliantly tapped Mia and Lucia from White Lotus Season 2 for its Valentine’s Day campaign, at the exact moment the two women were embedded in the zeitgeist 🤌

The danger facing celebrity brands is to be too closely associated with the celebrity. Kylie Jenner’s Kylie Cosmetics saw sales fall ~50% when Kylie took a break from posting to Instagram during her pregnancy. And this year, Adidas is set to lose $1.3 billion (!) from Yeezy after Kanye West’s self-destruction.

I tend to be more optimistic about celebrities and influencers as brand curators than as brand creators. Only a select few can build enduring de novo brands. But millions can be arbiters of taste, recommending to their communities what to buy. This is the thinking behind Flagship, mentioned above in the CAC section. Flagship’s business model is designed so that creators do what they do best—offer trusted recommendations:

The 800-pound gorilla in this category is still LTK (formerly LIKEtoKNOW.it), which just announced that it has a roster of 200,000 influencers driving $3.6B in annual GMV. The company boasts that 200 creators have made over $1M through affiliate on LTK.

One of the longest-running shifts in consumer behavior is trust migrating from corporations to people. Many shoppers would rather buy MrBeast Burger over McDonald’s, George Clooney’s Casamigos over Don Julio, Logan Paul’s Prime over Gatorade. We see this shift both in the rise of celebrity brands, though few have staying power, and in the long-tail curation of the influencer ecosystem.

5) Self-Expression

One of the biggest behavior shifts in Gen Z is a shift to more self-expression.

One interesting way this is revealing itself: weddings. The oldest members are Gen Z are 25, and they’re beginning to get married. A report last week found that a third of couples are choosing a wedding theme, up from 13% in 2017—examples include “Taylor Swift and Cats,” “Roaring ‘20s with Star Wars influence,” and “Vintage Nintendo.” And 40% of couples choose signature cocktails, compared with just 17% in 2017. (One thing that hasn’t changed: Ed Sheeran’s “Perfect” reigns as the most-chosen first dance song for the sixth straight year.)

We also see self-expression in the phenomenon of “committing to the bit.” Committing to the bit basically entails ironic consumption. In a piece in The Atlantic last week, Michael Waters told the story of 27-year-old Adonna Biel. Biel isn’t even a Pitbull fan, but she and her coworkers thought it would be funny to go to a Pitbull concert. So they committed to the bit: they rented a car they called the “Pitbus,” they bought Pitbull merch, and they even wore bald caps (Pitbull is famously bald). As a very casual Katy Perry fan who flew to Vegas last year dressed as a plastic bag, committing to the bit resonates with me.

Committing to the bit is a way of sampling identities, of trying on new forms of self-expression. Waters asks, “If committing to the bit means exploring the contours of a new persona, then perhaps it starts with a curiosity: What would it feel like to be that person for a day?”

Many Gen Z-focused brands say something specific about your personality: Madhappy means you value mental health; Dolls Kill means you’re edgy; Nensi Dojaka means you’re a “cool girl.” Expressing personality through clothes is nothing new, of course—but the torrid pace with which young people embrace and discard both their clothes and their identities is new.

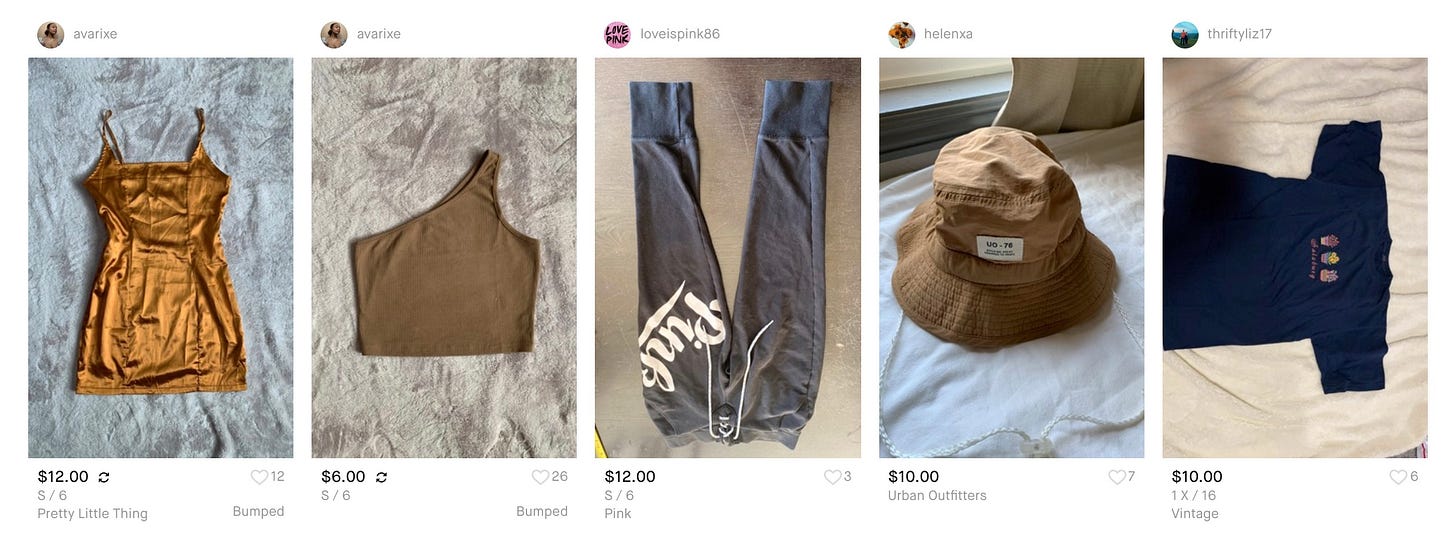

This is made possible by secondhand marketplaces. You can try one aesthetic, then sell those clothes on Vinted when you tire of them.

Or you can turn to even nicher marketplaces—Coscove, for instance, is a marketplace for cosplay costumes. Cosplay (a portmanteau of “costume” and “play”) is booming: one report estimated the cosplay costumes market to be $4.6 billion in 2020, growing to $23 billion by 2030, a 17.4% annualized growth rate. The tailwind? Self-expression.

One stat that surprised me: a Bain report found that the average Gen Z shopper makes their first luxury purchase when they’re 15, compared with 19 for their 30-something counterparts. Part of this embrace of luxury likely stems from the desire to use those products to achieve status or belonging. Part also comes from the fact that they can easily resell those goods on the internet, and move on to buy the next thing.

Part II

It’s no secret that I adore Taylor Swift. She’s the songwriter of our generation (I’m willing to debate anyone on this), and one of my greatest skills is that I can apply a Taylor Swift lyric to anything. A piece about how retail is changing in the digital age? No problem. From the song “Coney Island”:

We were like the mall before the internet

It was the one place to be

In the late 20th century, the mall was, indeed, the place to be.

Malls are a relatively recent creation. The first shopping mall sprung up in Missouri in 1922. With car production booming, malls were a convenient way to cluster a consumer’s shopping needs in one geographic location. In 1931, a mall in Texas had the idea to make stores face inwards, away from the street; this was the birth of the modern mall layout. The 1940s brought the rise of the suburban mall, and the 1950s saw malls tap department stores as “anchor tenants” surrounded by clusters of smaller retailers.

Malls soared throughout the late 1900s and into the early 2000s. That growth lasted until the financial crisis: 2007 was the first year that a new mall wasn’t built in the U.S. since the 1950s, and over 400 malls closed between 2007 and 2009. The recession, combined with the boom in e-commerce, spelled the end of the shopping mall’s heyday.

In my formative years, the mall was still the place to be. Food courts were the nuclei of middle school socializing. I went on my first date was to the Park Place Mall in Tucson, AZ (we each got rubbery slices of Sbarro). The “cool” stores were Hot Topic and Zumiez, Aeropostale and American Eagle, Billabong and PacSun.

PacSun provides an interesting case study of retail in the 2000s vs. retail today. PacSun had a big 2022 in part due to its investment in PacWorld, an expansive virtual world in Roblox. Roblox users could shop at PacSun through their blocky avatars. Last week, PacSun doubled down with its “Los Angeles Tycoon” world that lets Roblox users design LA neighborhoods, unlock dedicated pieces of a PacSun store, and wear 20 new digital items inspired by the brand’s Spring 2023 collection.

PacSun has adopted a “digital-first strategy,” in the words of its CEO, resulting in +30% sales growth over the past two years. The company’s reinvention captures how commerce has evolved from the shopping mall days to the internet-fueled modern era.

Technology is reinventing commerce. Last week, in Part 1, I looked at five forces shaping retail, from TikTok to CACs to celebrity brands. This week covers #6 through #10:

AI 🤝 Retail

Immersive Shopping

B2B Commerce Makes Life Easier

Sustainable Commerce

Don’t Discount Discounters

Let’s dive in.

6) AI 🤝 Retail

There are about 12 million items in Amazon’s inventory. If you expand that to include Amazon Marketplace’s third-party sellers, the number swells to about 550 million. Sifting through millions of products is already a challenge, made even more difficult by the various incentives at play. Brands, for their part, vie for paid placement at the top of search listings. Amazon, meanwhile, promotes its own private-label products: the company now has 118 distinct private-label brands, many carrying the Amazon name (Amazon Basics was the first private label, launched in 2009) and others operating in disguise (Solimo home products, Goodthreads clothing, Happy Belly snacks).

A search for “paper towels” yields four sponsored results (three from Bounty), followed by results from two Amazon private-label brands—Amazon Basics and Presto!

Amazon is famously customer-obsessed, but its shopping experience is deteriorating. That decline will only continue, as Amazon seeks to earn more from private labels: private-label brands typically have 25-30% higher profit margins. Amazon only gets about 3% of its sales from private labels today, compared to 59% for Trader Joe’s and 30% for Costco (Kirkland Signature is Costco’s private label). Target, for its part, owns 12 brands each worth $1B or more.

The bottom-line is: online shopping means sorting through a glut of products to figure out what’s actually good. This isn’t only a problem on Amazon; there are over 6.3 million Shopify Plus stores on Shopify. Consumers are tasked with extensive research on quality, price, and convenience.

So how does a consumer wade through mountains of stuff? With the help of AI-powered tools.

Vetted, a company we work with at Index, is an AI-driven product search engine. In the words of co-founder Stuart Kearney: “We founded Vetted because we felt that shopping online has become an overwhelming and frankly anti-consumer experience. People shouldn’t have to spend hours sifting through indistinguishable products littered across thousands of ad-infested sites loaded with fake reviews and unreliable information.”

Vetted is available on web or as a browser extension, culling information from reviews across Wirecutter, Reddit, YouTube, and other sites. The goal is to help shoppers make better and faster buying decisions.

We’re also seeing machine learning power discovery-driven shopping. Just as TikTok has infiltrated U.S. media, SHEIN has infiltrated U.S. fast fashion:

Here’s another view, comparing SHEIN to H&M and Zara sales:

SHEIN’s explosion is nothing short of remarkable: SHEIN has grown over 100% every year for eight straight years (!), and its latest private market valuation makes it worth more than Zara and H&M combined. Last June, SHEIN dethroned Amazon as the No. 1 shopping app in the iOS and Android app stores.

SHEIN’s velocity is something to behold: 2,000+ new items are added to SHEIN every day, while Zara adds 500 every week. SHEIN is basically an internet-native reincarnation of Zara and H&M, leveraging better technology to squeeze three week design-to-production timelines into three days. SHEIN combs competitor’s websites and Google Trends to figure out what’s in style, then creates designs quickly, forecasts demand, and adjusts inventory in real-time.

To bring us back to AI, one aspect of SHEIN that’s impressed me is its recommendations. Just as Bytedance anticipates the content you’ll want to watch, SHEIN anticipates the clothes you’ll want to buy. SHEIN is to commerce what Bytedance is to content. In The TikTokization of Everything, I wrote about how SHEIN is able to anticipate my needs and wants, based on limited data. From that piece:

Though Stitch Fix is now struggling, it was on to something groundbreaking—personalized commerce. The company just arrived at the concept a few years too early, when AI wasn’t yet sophisticated enough to take the place of a lengthy questionnaire and small army of data scientists. SHEIN is a step in the right direction, but we’re still only at the cusp of AI-driven recommendations.

Imagine a company that combs your camera roll and—with stunning accuracy—recommends a new wardrobe for you. Or the company simply asks you to link your Instagram account, and then it digests every like and follow you’ve ever made to deliver incredibly accurate, incredibly personalized fashion recommendations.

AI will continue to reinvent product recommendations, taking the onus off the consumer.

One final area for reinvention with AI: customized product design. Last week, I wrote about how Nike (always at the forefront of the industry) allows shoppers to design their own sneakers online and pick up in-store. That design process, though, is clunky and limited—I can tweak some colors and add my name, sure, but that’s about it.

What about when generative AI plays a part? I’ll be able to enter the text prompt “bright orange high-tops emblazoned with the swoosh and ‘REX’ on the back” and get a custom-made shoe in seconds. Everyone will become a product designer, unlocking new levels of personalization.

7) Immersive Shopping

Talking to Gen Zs, it’s clear that Millennial-era brands are back in vogue. We already covered PacSun, but J. Crew and Abercrombie & Fitch are also back with a vengeance. Some comebacks are the result of new leadership (creative director Olympia Gayot has injected new energy into J. Crew) and others are the result of ditching outdated and exclusionary norms (Abercrombie announced it would stop “sexualized marketing” and expand its sizes to include XL and XXL).

But many brands are “cool” again because they’re meeting young people where they are. PacSun’s Roblox world is one example. Nike, which consistently tops Gen Z rankings of favorite brands—20% of Gen Zs say it’s their favorite, well-ahead of #2 Apple (8.5%) and #3 Adidas (8%)—also has an expansive virtual world in Roblox, Nikeland. Players can outfit their avatars in Nike gear, unlock sports superpowers, and play soccer and basketball in Nike stadiums.

This strategy is savvy. Roblox users skew young—about 50% are 12 or under—and users spend a lot of time in Roblox: a recent Qustodio study made headlines for showing how TikTok is running circles around YouTube in daily engagement (113 minutes per day vs. 77 minutes per day, for daily actives), but Roblox trumps them both at a staggering 190 minutes per day, up 90% since 2020.

Brand presence in Roblox speaks to an interesting trend: more immersive digital shopping experiences. How do brands recreate the richness of offline shopping in an online realm?

We’ve seen Whatnot do so with livestreaming, leaning on charismatic sellers pushing product in real time. CommentSold has taken a similar tack, with far less fanfare, becoming one of the fastest companies to hit $1B in GMV by allowing sellers to simulcast across their websites, Facebook Live, Instagram Live, and TikTok Live. And newer startups like Showday let brands create interactive shoppable videos on their websites, either live or prerecorded.

Young consumers are early adopters of more immersive commerce: 47% of U.S. consumers who made livestream purchases last year were members of Gen Z. And while brands launch virtual worlds in platforms like Roblox, Minecraft, and Fortnite, those platforms themselves operate robust, immersive digital economies. Players spend billions of dollars a year on digital clothing and accessories using Robux, Minecoins, and V-Bucks.

I often think of social media as a march toward progressively richer media formats: Twitter (text) to Instagram (photos) to TikTok (videos). Commerce may follow a similar pattern, as innovative new products bring the richness of the analog world to online shopping.

8) B2B Commerce Makes Life Easier

The consumer-facing shopping experience has come a long way in the past few years. It’s hard for me to remember the last time I didn’t check out with Apple Pay. Business-to-business, meanwhile, lags far behind. Only about 5-10% of B2B transactions happen online and—in the year 2023!—about 50% of transactions are still done over the phone, over fax, or via in-person meetings with sales reps. The entire B2B ecosystem is inefficient, opaque, and convoluted.

In The $100 Trillion Opportunity in Marketplaces last fall, I wrote about how this is changing. The main example in that piece was Faire, which operates a wholesale marketplace between retailers and independent brands. Every year, U.S. consumers spend about $3.5 trillion. Independent retailers—small businesses with only a handful of employees and often just a single location—make up $750 billion of that spend, or about 25%. Faire digitizes that portion of retail.

There are many other examples of B2B innovation. Mable operates a similar model to Faire for specialty grocery. Fleek offers a B2B marketplace for vintage wholesalers, a fast-growing category. And Pepper, a company we work with at Index, digitizes how restaurants interface with their inventory suppliers, like providers of ingredients, utensils, and packaging. What was once a massive headache becomes fast and simple.

As my partner Damir puts it, “While the frontend of the restaurant is benefiting from technology, the backend has not received the same attention.” That trend is true across commerce: B2B innovation lags B2C innovation (the problems are less obvious), but B2B is often an even bigger prize. A new generation of startups aim to bring B2B spend and manual workflows into the 21st century.

9) Sustainable Commerce

Simply put, retail is bad for the environment. Retailers are responsible for about 25% of global carbon emissions. Scientists estimate that, globally, 35% of the microplastics found in oceans can be traced to textiles. Going back to the SHEIN example earlier, 95.2% of SHEIN clothing contains new microplastics.

The good news is that, 1) consumers are waking up to the problem, and 2) they’re pressuring brands to clean up their acts. The shift to more sustainable commerce—arguably the biggest retail shift of this generation—can be seen across various sub-sectors of commerce.

Secondhand is an obvious one, as consumers look to buy used and to recycle products. Resale is a $40B market expected to double to ~$80B by 2025 and to triple to ~$120B by 2030. By 2030, the secondhand fashion industry will be nearly twice the size of the fast fashion industry. On the B2C side, marketplaces like Depop and Vinted ride this tailwind. On the B2B side, companies like Archive and Reflaunt power resale for brands. In my mind, resale is still relatively unsolved by software; there’s a lot of work to be done to unlock supply, which is a thorny problem.

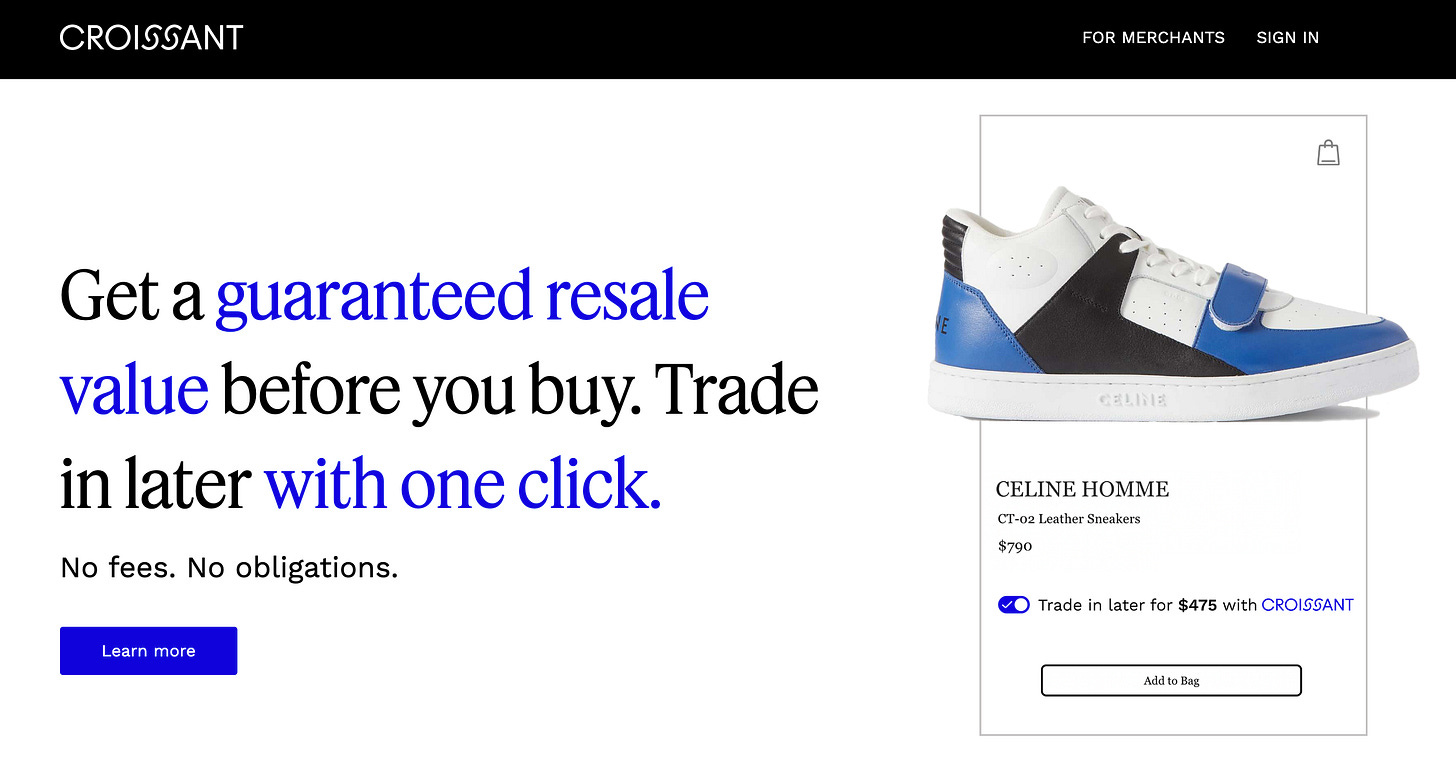

One interesting new area is recommerce at checkout. Naturally, consumers are more likely to convert (and spend more) if they know the estimated resale value of the item they’re buying. If this flow can also lessen the future logistics burden of resale (pulling in product details, for example), it can unlock latent supply. Examples here are AirRobe and Croissant.

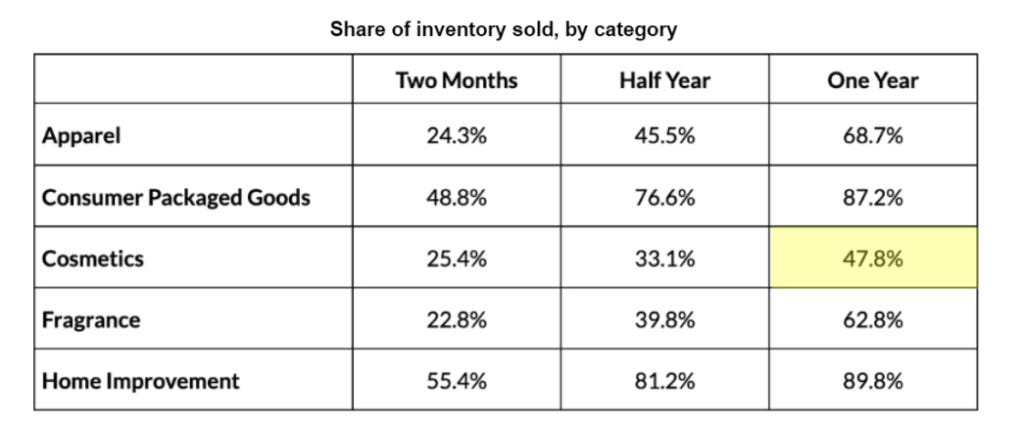

Another sub-sector within sustainable commerce is managing excess inventory. Brands overproduce more than $500B of goods annually. I like this chart from USV’s Hannah Murdoch and Rebecca Kaden, which shows that in some categories, like cosmetics, less than half of inventory is sold:

Much of this unsold product ends up in landfills like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which covers 1.6 million square kilometers in the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and California. The garbage patch is growing exponentially, swelling 10x each decade since 1945.

Excess inventory is a big problem. In 2017, a Swedish power plant abandoned coal as a source of fuel, instead choosing to burn mountains of discarded clothing from H&M. You can’t make this stuff up.

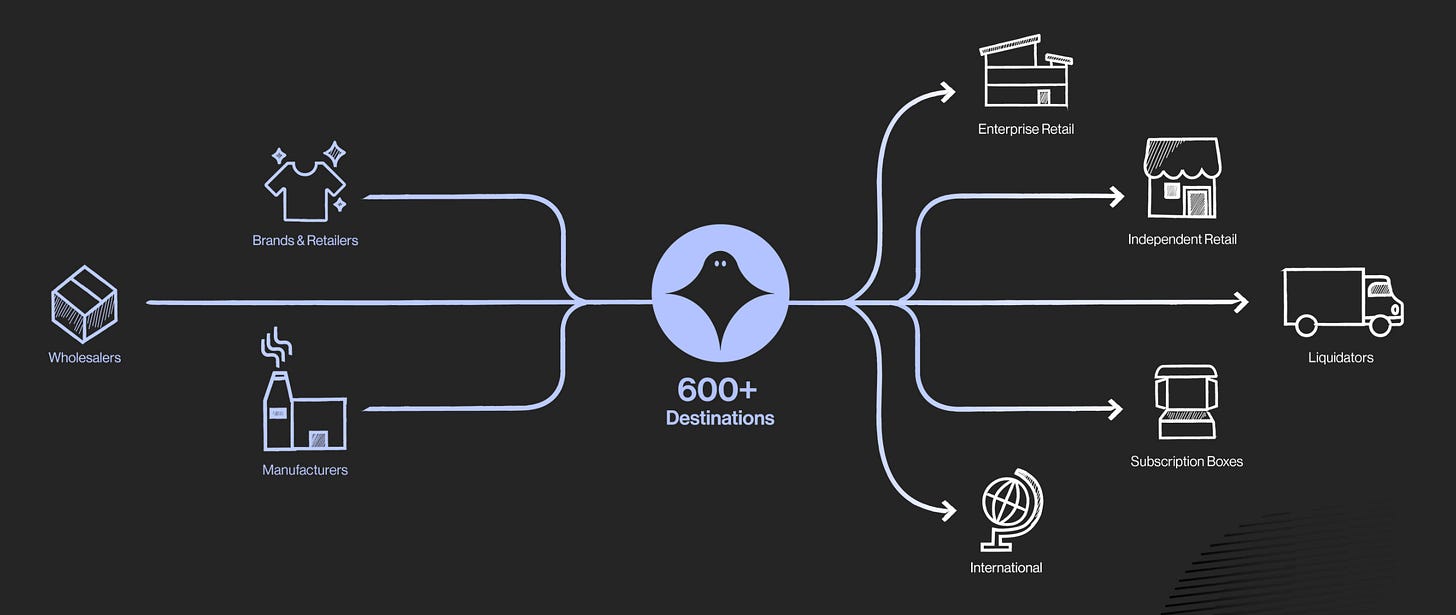

New startups are helping brands manage solve this problem. Ghost, for instance, is a B2B platform that allows brands to route surplus product to the right channels.

Sometimes this means liquidators, but increasingly this means off-price retailers. Better-managed excess inventory means increased supply for discounters, which are more in demand than ever. This brings us to the final force shaping retail…

10) Don’t Discount Discounters

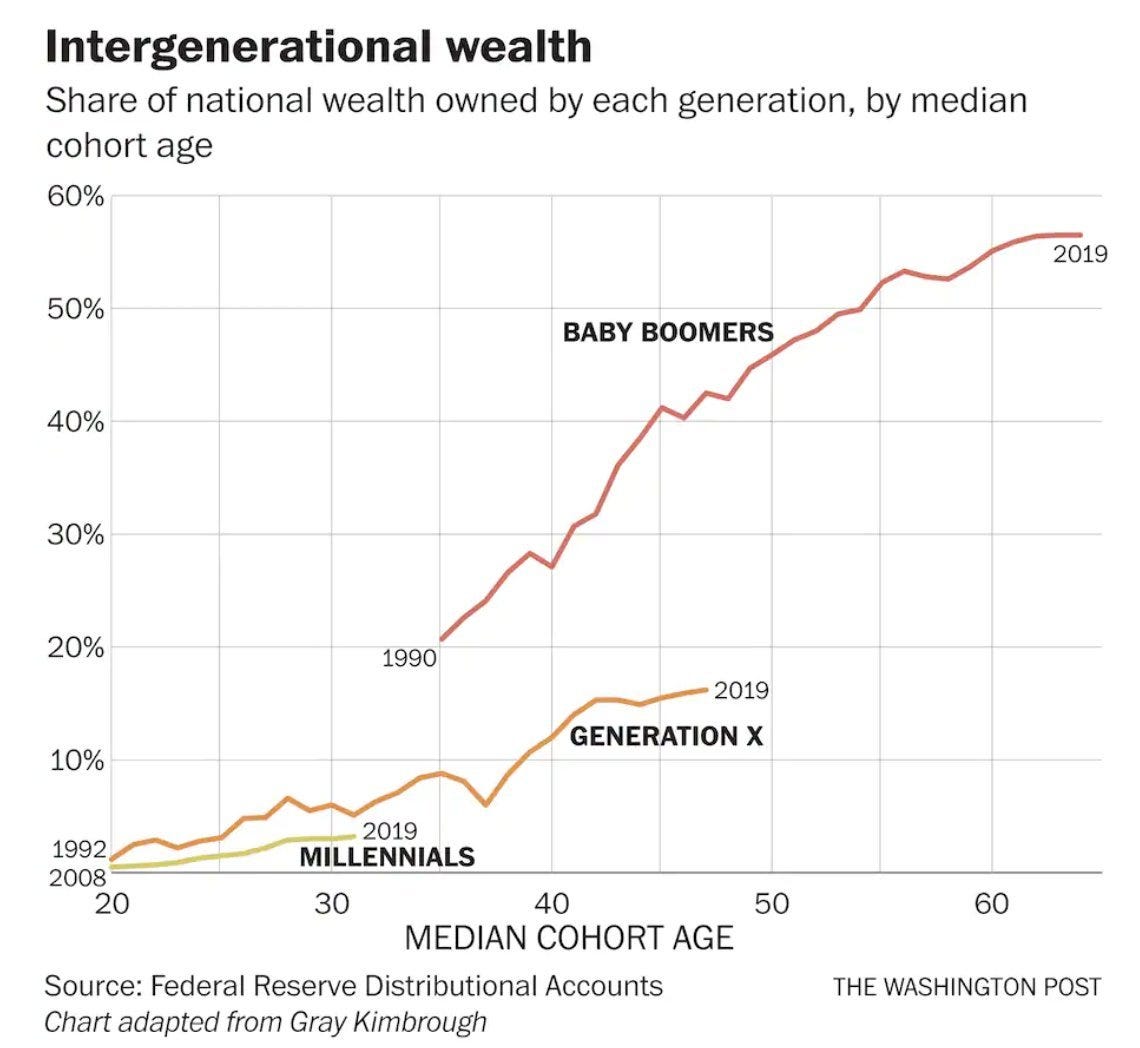

Just as malls have gone out of fashion, so has the middle class. This chart from The Washington Post tells us a lot about younger consumers’ purchasing power:

The Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, continues to creep higher and higher:

One consequence of the disappearing middle class is a boom in discount retailers. The top six retailers opening stores in 2022 were all dollar chains and discounters, led by Dollar General, Family Dollar, and Dollar Tree. In 2021, nearly 1 in 3 new chain stores opened in the U.S. was a Dollar General.

Young consumers are pessimistic. A study by McKinsey last year found that a quarter of Gen Zs doubt they’ll be able to afford to retire, and less than half believe they’ll ever own a home. Inflation exacerbates the problem, eroding the purchasing power of wages and savings. Procter & Gamble, which makes everything from Crest to Pantene to Gilette, just reported that it raised prices 10% year-over-year. Consumers feel the hurt.

Startups are also getting in on the rise in discounting. Ditto is a social shopping app that helps brands sell their excess inventory, passing savings along to consumers with dirt-cheap deals. In some ways, it aspires to be an online version of TJ Maxx, which counts $50B in revenue but only 2% digital penetration. Temu, meanwhile, exploded last fall and has remained at the top of the App Stores for months.

Temu is effectively an online dollar store, owned by the Chinese e-commerce giant Pinduoduo. Pinduoduo is following the Bytedance playbook of spending aggressively on user acquisition to win the U.S. market. Part of that plan included not one, but two Super Bowl commercials (costing $7M apiece). The strategy seems to have worked: Temu saw a 45% surge in downloads and a 20% uptick in daily active users on the day of the Super Bowl.

But Pinduoduo is no doubt bleeding money on Temu. E-commerce is challenging for discounters; the unit economics often don’t work. (How do you profit on shipping a bunch of $1 items from China to the U.S.?) There’s a long history of startups that have attempted discount retail online, but failed. Temu is the latest to tackle the space, with a $110B market cap company behind it, but the jury is out on whether it can ever make the math work.

Final Thoughts: The Fusion of Offline & Online

Consumer spending makes up two-thirds of the U.S. economy. Our lives revolve around commerce. That’s been true for millennia, with only the venue changing. Hundreds of years ago, it was the town square. In the 1900s, it was the shopping mall. Today, it’s online. Taylor Swift’s lyrics hold true: today, the internet is the place to be. Technology is working its tendrils into every facet of retail.

If there’s one overarching trend of commerce in the 21st century, it’s the fusion of offline retail and online retail. The holy grail for a brand is to merge atoms and bits, building relationships with customers in both the physical and digital worlds.

The most pioneering brands find new ways to do so. Nike, for example, allows buyers to design sneakers on its website, and then pick them up in-store. Glossier began as a direct-to-consumer e-commerce brand, but is now launching its much-hyped, stunning Soho flagship—and more importantly, you can now buy Glossier products in Sephora. Omnichannel is the future.

For the first time since 2016, physical store openings exceeded closings in 2022. And this year, retailers plan to open 3x more stores than they close, as pandemic-driven hesitations around brick-and-mortar give way. Shoppers clearly want a tight tether between online and offline.

Many of the companies mentioned in this piece are B2C—SKIMS and Vinted, for instance. But even more are B2B—Catch and Beam, Flagship and Minoan, Northbeam and Triple Whale. They power a new infrastructure for an omnichannel, technology-infused retail revolution.

What’s fascinating about the retail landscape is how rapidly the consumer experience is evolving. Shopping in 2023 looks very different than shopping in 2013—and shopping in 2033 will likewise stand in stark contrast to shopping today.

Sources & Additional Reading

Two of my favorite newsletters on commerce and consumer behavior are Daily Consumer by Damir Becirovic and After School by Casey Lewis

How Young People Spend Their Money | The Economist

TikTok Interns | Sapna Maheshwari, New York Times

Don’t Be Embarrassed to Commit to the Bit | Michael Waters, The Atlantic

One of the best reads on “the advertising recession” caused by ATT: The ATT Recession, by Eric Seufert

The History of Malls in the U.S. | Sunset Plaza

The Fashion Industry’s Environmental Impact | Bloomberg

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week:

![OC] Fast fashion companies add new items to their sites all the time. Shein is the worst, with 60,000 new items each month. : r/dataisbeautiful OC] Fast fashion companies add new items to their sites all the time. Shein is the worst, with 60,000 new items each month. : r/dataisbeautiful](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!atis!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F888530a0-1cc0-4080-95df-2569b6614954_3600x3600.png)