The Rise of Cash App 🤑

Examining the World's Most Underrated Social Network

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

The Rise of Cash App 🤑

There’s one “company” that’s among the largest consumer tech businesses in the world, but that I’ve rarely written about in Digital Native: Cash App. Cash App gets overlooked in part because it’s a subset of Square Block, rather than a standalone company. But it shouldn’t be overlooked—it’s an impressive business: Cash App has been the #1 finance app in the App Store for five years running, has 80 million users, and last year was the 8th-most-downloaded app in the U.S. across all categories.

If you’re a finance company sitting alongside the likes of TikTok and Instagram, you know you’re doing something right. Cash App is a fascinating case study in product, growth, and branding.

Last week, reading through Block’s investor day presentation of Cash App, I was struck by how Cash App isn’t only one of the most underrated fintechs in the world, but also one of the most underrated social networks. Cash App saw something that most financial services companies hadn’t: money is inherently social.

Much of Cash App’s success owes to the fact that from the beginning, its team approached it not like a bank, but like a social network. What other financial services company would showcase its business lines with a slick visual like this?

In fact, all of Cash App’s design oozes coolness. It’s loud and splashy and fun. It’s playful. It makes you want to go hug a designer.

Let’s back up for a minute.

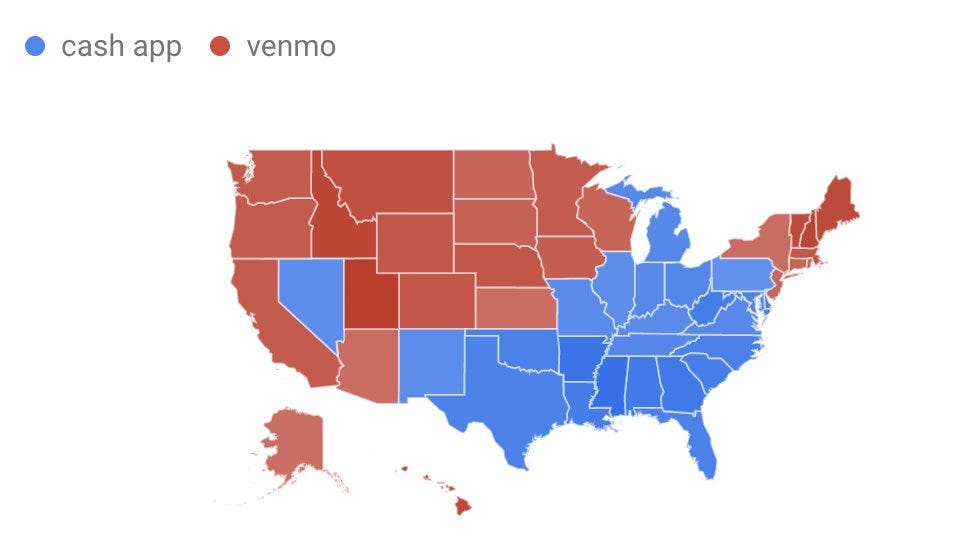

When Cash App launched in 2013, it was already behind. Venmo had launched four years earlier in 2009, and had already infiltrated major urban centers like New York and L.A. New college grads were Venmoing each other for cab rides and sushi dinners and karaoke nights. “What’s your Venmo?” was solidifying its place in the vernacular. The thing about peer-to-peer payments is that they have hyper-local network effects: if all your friends are on Venmo, chances are you’re on Venmo too. Most people don’t have both Venmo and Cash App downloaded on their phones. Cash App realized this from the start.

So Cash App turned to the places that Venmo had overlooked—often lower-income communities, and specifically communities in the American South. Cash App launched in Atlanta (it was called Square Cash, initially) and quickly took hold in the region.

Unbanked and underbanked communities embraced Cash App. As Jack Dorsey put it, “People use Cash App as their primary bank account, and in some cases their only bank account.”

Many Cash App users were Black, and Cash App’s network effect became especially strong in the Black community. Rappers began to rap about Cash App—unheard of for a finance company. Here’s what a search for “cash app” on Spotify returns:

The rapper Amine said, “This isn’t even just rap, this is just Black culture in general. Venmo is people in your business, and we don’t like people in our business. Venmo is made for white culture. ‘Drinks with Sarah.’ The 🔌 for the electricity bill. Venmo’s like the feds.”

Square saw how Black culture was embracing Cash App and leaned in. They tapped Travis Scott to give $100K to fans through Cash App. They then topped that with a $1M giveaway through Lil Nas X. When WAP came out, they partnered with Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion for #WAPParty.

A major financial services company was working with artists on a song about…well, you probably already know. Goldman Sachs would never.

And Cash App didn’t stop there. The team got creative across the board, revisiting long-held beliefs about how and where finance companies should market. The Cash App team bought advertisements on Joe Rogan’s podcast. They sponsored an e-sports tournament. They worked with Kim Kardashian.

Slowly, Cash App’s pervasiveness in the culture allowed it to spread across the country. It began to creep onto Venmo’s turf.

In 2018, Cash App surpassed Venmo in total users, and over the past four years, the gap has widened. Google search interest shows that the country is still split geographically (those network effects, remember?), but Cash App is winning.

Of course, viral marketing and sleek design are nothing without product innovation. But Cash App has that in spades too.

Cash App started with a peer-to-peer payments product. Its premise was simple: people don’t want to wait in long lines at the bank, and they shouldn’t have to. In a world where we all have supercomputers in our pocket, we should be able to do all our banking from our phones.

Cash App’s mission is to “redefine the world’s relationship with money by making it more relatable, instantly available, and universally accessible.” Over time, Square began to layer on more products to achieve that mission. In an excellent Twitter thread about Cash App, my partner Mark Goldberg pointed to Square’s insane product velocity:

Cash App’s product launches increase the gross profit per user. Cash App now has four separate products that will each do $200M in gross profit this year: Instant Deposit, Cash App Card, Bitcoin, & Business Accounts.

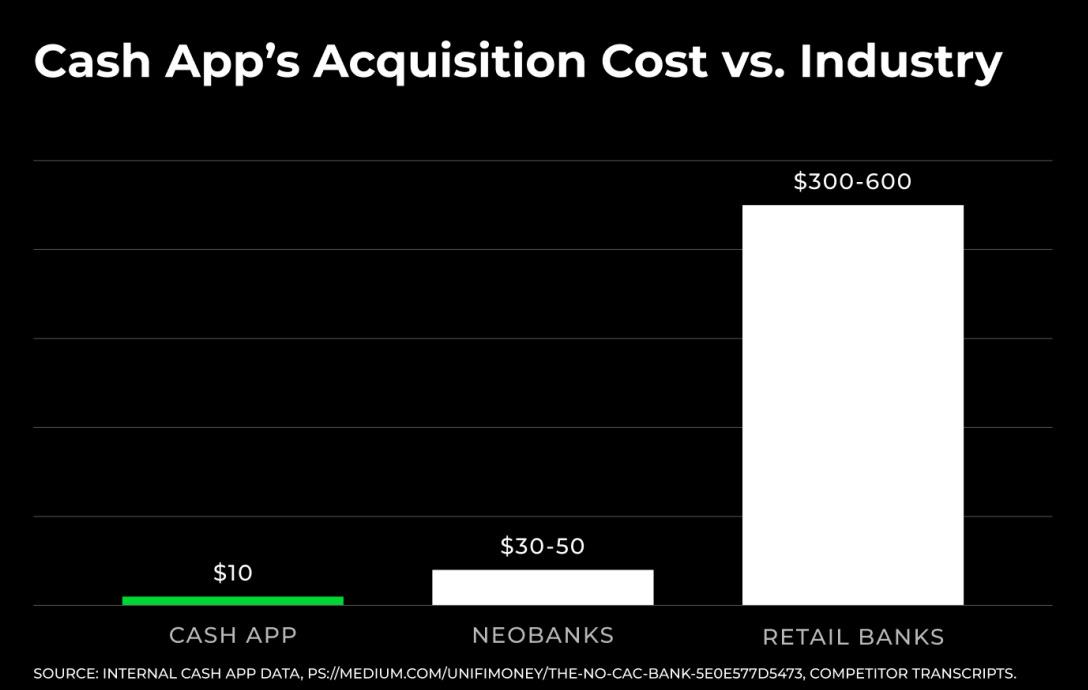

When you think about a company’s unit economics, there are two sides to the equation: customer acquisition cost (how much it costs to acquire a new customer), and customer lifetime value (how much that customer is worth). Cash App has layered in new products over time to increase the customer LTV side of the equation:

And the Cash App team’s savvy marketing—embedding Cash App into culture—has driven down the CAC side of the equation. Retail banks pay $300+ to acquire a customer. Neobanks pay $30+. Cash App pays just $10.

Cash App acts like a social network because it is a social network. Cash App sees a 31 percentage point increase in retention when a user has 4+ friends on the app. The product is designed to integrate social features, which in turn improve unit economics.

We don’t view Cash App as a consumer social company, but we should. Venmo, similarly, has long been a social network in disguise 🥸 Venmo is where you can see that Aaron paid for Cady’s Uber home from the bar (gasp!), that your ex has been going on lots of coffee dates with some guy named Shane (ugh), and that Gretchen invited Karen to her bachelorette but didn’t invite you (honestly, such a Gretchen move). Pro tip: go set your Venmo default to “Private” 👀

Revisiting Cash App’s story has made me think about a certain type of social network—the utility-based social network. These are social apps that serve a core purpose (e.g., peer-to-peer payments), but that also layer on social features to improve growth and retention. In some ways, utility-based social networks evoke Chris Dixon’s “Come for the tool, stay for the network.” You download the app to accomplish a job to be done, but you stay for the community.

Instagram started as more of a tool than network—the app was primarily a photo-editing app, where you could overlay cool filters onto your pictures. Rapidly, though, the network overpowered the editing tools.

There are other examples of utility-based social networks. Let’s take three of them:

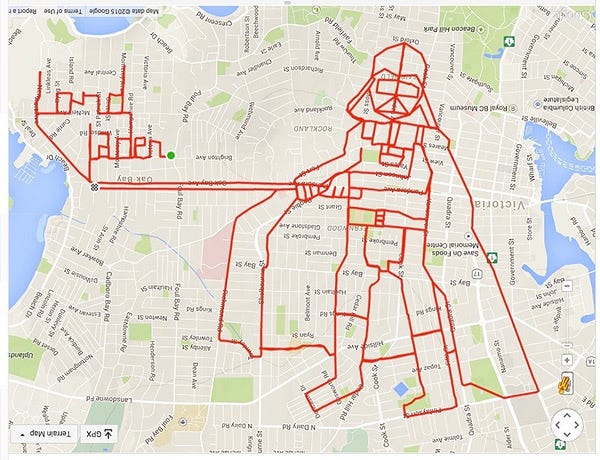

At first blush, Strava looks like a fitness app for tracking your runs and bike rides. But Strava is actually a robust social network for fitness enthusiasts. It’s Strava’s social features that keep users coming back every day. Who wouldn’t want to see their friend’s Darth Vader-shaped bike ride?

Or who wouldn’t want to be proposed to (!) via a carefully-planned running route?

Another example of a utility-based social network is Greg, an app for plant care. Greg serves a real purpose: the app uses machine learning to predict the water needs of your plant 🪴 Without Greg, my plants would no doubt have died a painful death months ago. But Greg is also social: you can share photos of your fiddle-leaf fig, and admire the health of your friend’s bird of paradise. For any proud plant parent, these social features are catnip to keep you returning to and engaging with Greg.

And we’re seeing new utility-based social apps emerge. Copper is a new app for authors and readers to discover and share book recommendations. For book enthusiasts, Copper is quite useful. But Copper is also a social app. In the words of its founder, Allison Trowbridge: “You have Twitch for the gamers, and Etsy for the crafters, and Spotify and SoundCloud for the musicians. Authors have never had a platform that’s built around their needs.” Copper has text-based forums and video-based Q&As built around books.

Like Cash App, Strava, Greg, and Copper are functional—they serve real purposes, beyond socializing. But they’re also sticky and enjoyable because of their social components. We’re social animals, and over time all consumer companies gravitate (in some way) toward social. Even the most utilitarian of consumer companies, like Amazon, have social features—reviews, community forums, affiliate programs.

Cash App is running circles around banking incumbents by reinventing the finance playbook. If you’re consumer-facing, regardless of vertical, the lessons are clear: don’t neglect design; think from first principles about how to reach people; and learn from your users about how they perceive you and what they want from you.

Sources & Additional Reading

Cash App Block Investor Day Presentation | May 2022

Check out my partner Mark’s Twitter thread on Cash App here and a piece about how fintech went from the business section to the style section

Cash App Is Culture | Alex Johnson

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: