This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

The Rise of the Digitally-Native Job

Walmart is the largest private employer in the United States, and the second-largest overall employer after the federal government. Globally, Walmart employs 2.3 million people; in the U.S., it employs 1.6 million (about 1% of America’s total workforce).

Amazon is catching up quickly, with 1.1 million U.S. employees and 1.6 million global employees—already double the 798,000 people employed by Amazon in 2018. (Walmart’s workforce has actually contracted slightly in that time period.) Over the next few years, we’ll likely see Amazon surpass Walmart as America’s largest private employer.

What’s unique about Amazon is that the company provides far more people with a livelihood than the employees captured in its own payroll expense. About 9.5 million sellers earn income on Amazon’s platform.

This gets at a unique property shared by many of the most successful technology companies: they create ecosystems that employ more people than they do themselves. The ecosystem effect Amazon created doesn’t apply to Walmart in the same way—yes, Walmart gives brands shelf space (thereby creating jobs for their makers), but it does so in a much less self-serve and scalable way. I often think back to Chris Anderson’s 2004 piece in WIRED, The Long Tail:

As egalitarian as Walmart may seem, it is actually extraordinarily elitist. Walmart must sell at least 100,000 copies of a CD to cover its retail overhead and make a sufficient profit; less than 1 percent of CDs do that kind of volume. What about the 60,000 people who would like to buy the latest Fountains of Wayne or Crystal Method album, or any other non-mainstream fare? They have to go somewhere else.

The same concept applies to sellers—what about the people who might not move enough product to warrant shelf space in a Walmart? They, too, have to go somewhere else. Many niche sellers have existing latent demand, and need the internet to unlock that demand: in 2000, the average Barnes & Noble carried 130,000 titles, and yet more than half of Amazon’s book sales at the time came from outside its top 130,000 titles.

The ecosystem question is one I often ask myself as an investor in startups: if this company is successful—if it really works—can it become a platform for massive job creation?

I’m fascinated by job titles that are digitally-native—that wouldn’t exist without the internet or, often, without a specific underlying tech company. Three examples from the Index portfolio:

Discord Community Manager—there are 19 million weekly active servers on Discord, and many employ managers to run the show

Roblox Developer—Roblox has 300,000+ developers building Roblox experiences

Etsy Seller—Etsy has 7.5 million active sellers from 234 countries

These job titles didn’t exist 10 or 20 years ago. To make the concept of digitally-native work more tangible, let’s revisit three examples of specific people I’ve written about in the past:

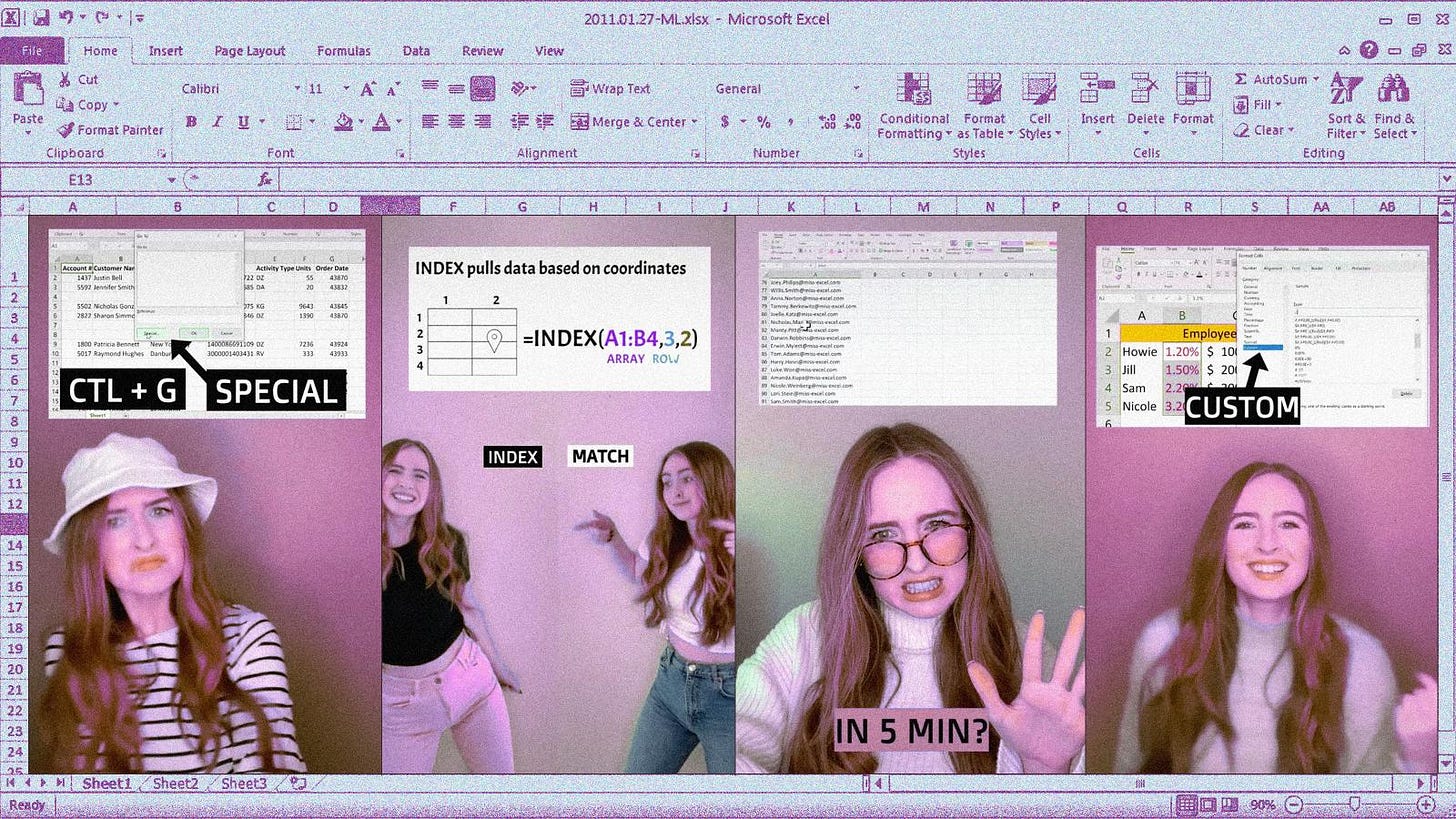

Miss Excel

Miss Excel—real name: Kat Norton—has over a million followers on TikTok and Instagram, where she posts content about (you guessed it) Excel. But Norton’s social channels really act as a funnel for her Excel training courses, sold here. She earns up to six figures a day selling her courses, all as a one-woman business.

Miss Excel has two digitally-native job titles—TikToker and “Excel online course creator”—that didn’t exist a few years ago. And her income is largely passive: she travels the world, working just a few hours a week to make content, while her evergreen Excel course flies off the proverbial shelves.

KARRA

The artist Kara Madden (who goes by KARRA) moved to LA to try to make it as a singer. But after a few years, she found herself managing a Jersey Mike’s and making under $10K from music, mostly from singing on My Little Pony commercials. Then she uploaded a pack of vocal hooks to Splice, a site that lets artists sell royalty-free sounds as component parts—atomic units that can be assembled by other creators into fresh works. KARRA has now made over $300K on Splice.

Splice costs $9.99 a month and gives users access to 2 million sounds, all royalty-free. It has 4 million users. KARRA’s vocal pack included wordless melodies and hooks like “don't wanna wake up” and “loving you.” David Guetta even used her samples in a song. In aggregate, Splice has paid out $40M+ to artists.

One board member says: “The music industry of 2017 wouldn’t have found KARRA in a million years. They weren’t looking in the right places for artists with superstar potential.” And in KARRA’s words: “Splice opens the doors for literally anyone to become a producer.” “Splice artist” is another job title that didn’t exist a few years ago, but that can now support a person’s livelihood.

Bella McFadden

Bella McFadden is a professional reseller on Depop, a secondhand clothing marketplace popular among Gen Zs (90% of Depop users are under 26). In 2020, McFadden became the first person to make over $1 million selling on Depop. She’s sold 64,936 items (!) through her Depop store, which has 380,000 followers.

McFadden spends her days sourcing products from outlets and cataloguing them based on their aesthetic, studying 90s fashion magazines for inspiration. She then photographs and lists the items, saying, “I start shooting at about 8 in the morning, and don’t finish till 7 or 8 at night.” Most of her products sell for between $15 and $25, so she needs to sell volume. She also charges $200 for personal styling, designing and curating an entire outfit based on her client’s aesthetic.

There are now entire armies of professional resellers on Depop, Vinted, Poshmark, and Facebook Marketplace.

Emergent Ecosystems

One of my favorite quotes about the internet—and one I’ve shared often in Digital Native—comes from Patreon’s Jack Conte: “You may have grown up in a small town, where you were the only person out of 1,000 people with a specific interest. But there are 4.5 billion people on the internet, meaning that there are 4.5 million people who share your interest. Online, no niche is too niche.” The same idea can be adapted to finding work: if only 1 in 1,000 people is interested in what you’re buying, that’s a customer base in the millions. If only 1 in 1,000,000 people is interested, that’s still a customer base of 4,000+—depending on your average selling price, potentially enough to sustain a living.

Many online marketplaces, social media companies, and content platforms fit into the “ecosystem” category. These are often the largest businesses, and the ones with the strongest network effects. But successful software companies can also facilitate job creation. Take Squarespace. Squarespace now offers Squarespace Marketplace, where you can browse and hire web designers.

Here’s the first profile surfaced to me—Bohdan, a Ukrainian developer offering a variety of services. Bohdan may make his entire living on Squarespace: if he’s hired to build one site each week, that’s $50,000+ in annual income.

These examples—from Roblox to TikTok, Etsy to Squarespace—are companies that have been around for years. But there are also newer ecosystem startups emerging.

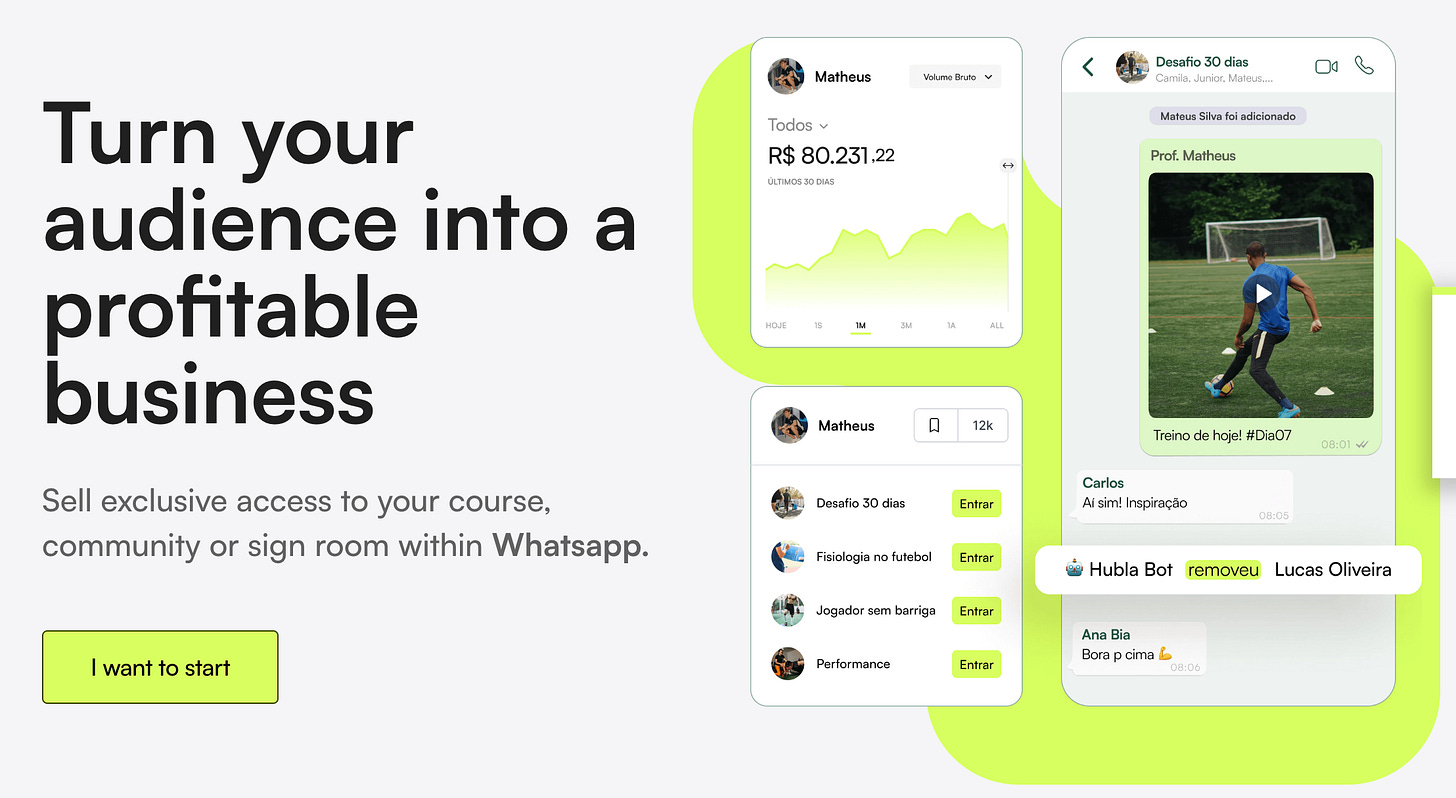

Some of these startups are building on other platforms. There are many companies, for instance, now building on WhatsApp. This is particularly true in Latin America, where WhatsApp is society’s connective tissue. Hubla is a Sao Paulo-based startup that lets people sell access to a course or community through a WhatsApp group:

Then there are other recent startups that themselves are becoming ecosystems for job creation. To look at three examples:

Office Hours

Office Hours is an expert network platform. Many people—particularly bankers, consultants, or investors—may be familiar with traditional expert networks like GLG and Alphasights. Office Hours extends that concept to the long tail, tapping into latent knowledge. Here, under the Product Management category, I can book time with leading product and engineering thinkers:

If you’re a doctor, you have incredibly specialized knowledge, but your income is largely capped. You could use Office Hours in your free time to earn more.

Many experts likely use Office Hours for supplemental income, but the site could theoretically become the single platform underpinning a career. Anyone with deep domain expertise—which is nearly everyone, on some subject—can become a full-time expert and monetize that knowledge.

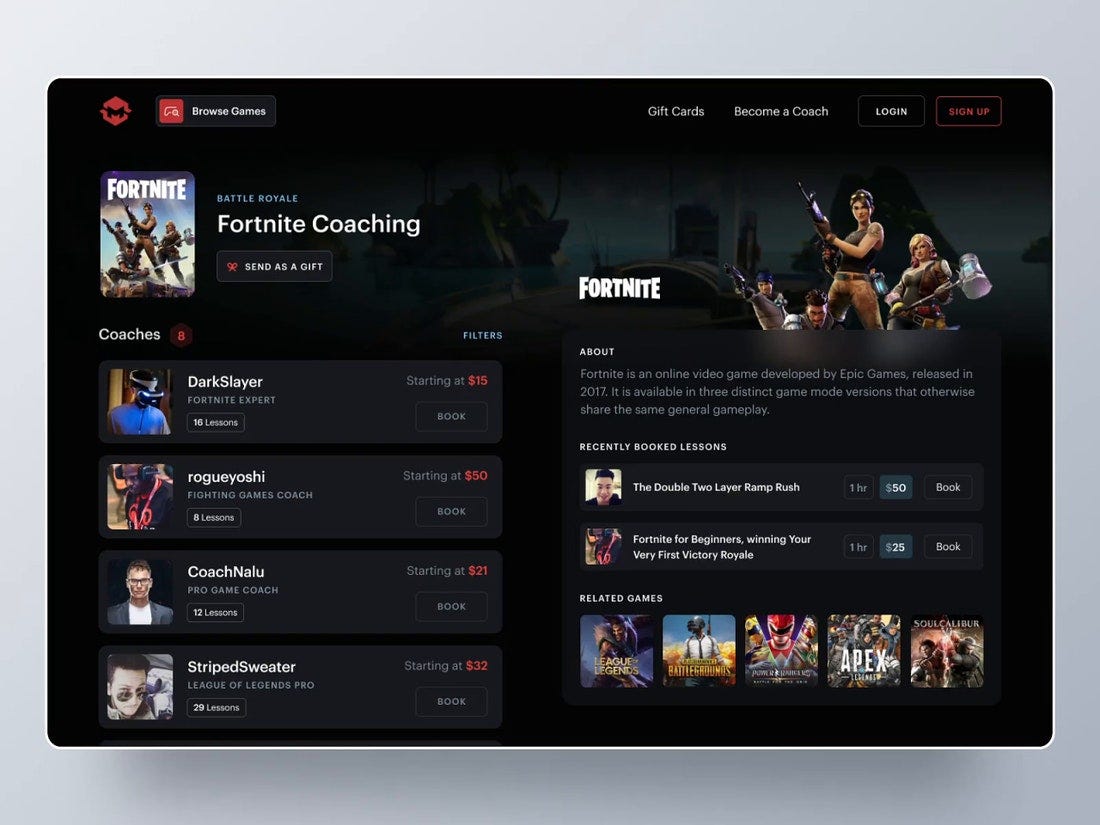

Metafy

Metafy is a place where you can book 1-on-1 coaching sessions with the world’s best gamers. In this screenshot, you can see that you can book DarkSlayer, a Fortnite expert, starting at $15, or StripedSweater, a League of Legends pro, starting at $32:

The gaming industry is set to be worth over $400 billion by 2028, and there are 3 billion gamers globally—nearly 1 in 2 people on the planet. Yet before Metafy, there wasn’t a systematic way to learn from the best. “Metafy Coach” is now a viable career opportunity.

Whatnot

Whatnot has exploded over the past few years as a livestream commerce destination, first in collectibles (think Pokemon and Funko Pops), and now across categories. I’ve used the example before of Li Jiaqui, known in China as the “Lipstick King.” In a typical livestream, Li will show off a lipstick for his viewers. Viewers ask questions in real-time—“How vibrant is the color?” “Does the lipstick also moisturize chapped lips?”—and Li answers their questions live. Then, he’ll offer a discount to create urgency to buy—“Buy now and get 15% off this lipstick.”

Li once tried on 380 lipsticks during a 7-hour livestream, and then sold 15,000 lipsticks in just five minutes (!). Last October, he sold $1.7 billion worth of product during a single 12-hour livestream; 250 million people tuned in.

Not everyone is the Lipstick King, but livestream selling can still be quite lucrative. In its pitch to prospective sellers on its site, Whatnot points to an average of $6,000 a month in earnings:

The West still has a ways to go to catch China, where being a livestream seller has become been a sought-after career and where livestream commerce is now a $550B industry, +60% year-over-year. But platforms like Whatnot expand the opportunity to be a professional seller beyond the QVC screen and into the long tail.

Final Thoughts

The internet has led to a Cambrian explosion in entrepreneurship—and a complete rethinking of how we earn a living. The rules are still being rewritten.

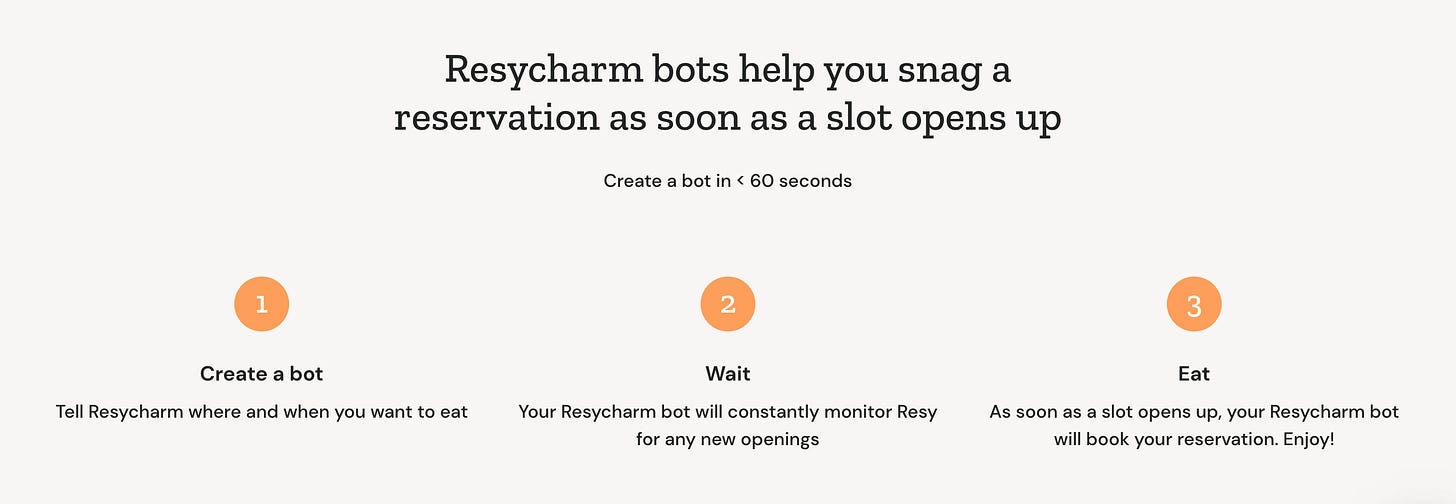

My friend—who has a separate full-time job at a startup—recently created Resycharm on the side. Resycharm is a bot that helps you snag a coveted restaurant reservation. If you’re worried about tables at Carbone filling up, Resycharm has you covered. You only get charged for successful reservations, $20 per seat across all restaurants.

It’s a brilliant product, and one with (based anecdotally on my friends, at least) a lot of pent-up market demand. But it also speaks to new ways that people are earning income online. My friend could, theoretically, build that bot and then sit on a beach somewhere, earning a nice living off of FOMO-driven college grads clamoring to get into Don Angie.

There’s an entire community called IndieHackers where people share how they built their online businesses and where they strategize ways to grow. It’s a community for people who have internet-native jobs that they’ve built for themselves.

Many of the generational businesses in the 2020s and 2030s will expand the same concept, allowing millions of people to build careers on top of their platforms. I’m curious what other “ecosystems” are forming today—if I missed one here, or if there are new entrants not on my radar, I’d love to learn about them.

Sources & Additional Reading

Thank you to Chris Paik, Jordan Cooper, Ian Spear, and Georgia Stevenson for being thought partners on many of these topics

The story of Miss Excel in The Verge

Splice & KARRA in Billboard

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: