The Seven Deadly Sins of Consumer Technology

Investing in Lust, Pride, Sloth, Greed, Envy, Wrath, and Gluttony

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

The Seven Deadly Sins of Consumer Technology

The seven deadly sins are a classification of our most fundamental vices—the negative personal characteristics that are human nature, and that we all find ourselves subject to. The origin of the seven deadly sins can be traced back to Christianity in Ancient Egypt, and the list has been refined over the centuries.

In short, the seven deadly sins are:

Pride

Sloth

Envy

Greed

Gluttony

Lust

Wrath

In our modern times, people might be most familiar with the seven deadly sins from the (excellent) 1995 hit movie Seven, ironically the year’s 7th-highest-grossing film. Without spoiling too much, Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman play detectives tasked with hunting down a serial killer who murders his victims based on the seven deadly sins.

For instance, one victim is a model whose face he mutilates; she’s given the option to call for help and live disfigured, or to commit suicide by taking pills. She chooses suicide, and her death thus represents Pride. Another victim is a morbidly obese man forced to eat until his stomach bursts (Gluttony), and another is a man strapped to his bed and forced to starve to death (Sloth).

Seven pushed the seven deadly sins back into our pop culture vernacular, beyond religious confines. And in the years since, the seven deadly sins have become part of our tech vocabulary too.

In 2011, Reid Hoffman declared, “Social networks do best when they tap into one of the seven deadly sins.” Ever since, people have built on his framework, often using the same tried-and-true examples: Facebook as Envy, Tinder as Lust, GrubHub as Gluttony. (Hoffman is the founder of LinkedIn, itself a mix of Pride and Greed.)

I would expand Hoffman’s statement to encompass consumer companies writ large. And I like his framework because it captures a key truth: human behavior is the engine of consumerism, capitalism, and culture. What’s more, human behavior doesn’t really change. Yes, each generation brings new ideas and worldviews, but we’re all fundamentally the same, shaped by millions of years of evolution: we all get angry; we all get jealous; we all need to feel respected.

Of course, the seven deadly sins framework filters things through a negative light, and companies building on a sin aren’t inherently bad. It’s normal to feel these emotions, and every consumer-facing company—in some way—taps into the negative emotions as well as the positive. Social networks, for instance, are as much about spreading kindness as they are about spreading malice. They are conduits for human communication, which runs the full spectrum of emotion. Both the good and the bad fuel network growth.

A decade later, the seven deadly sins framework is due for a refresh. This week, for each sin, I’ll dive into one example of a more mature tech company, and one example of a more recent startup building on that sin. Let’s jump in.

🪞 Pride

What better place to start than Reid Hoffman’s creation, LinkedIn? LinkedIn personifies Pride. In the early days of the company, LinkedIn’s founders were surprised to find that, curiously, there was one profile that people seemed to visit far more than any other: their own. It turns out that people love to curate and admire their own achievements.

Today, LinkedIn has 830 million registered users, and about 50% visit the site every month. LinkedIn profiles have become our modern-day flex for professional accomplishments, a public version of a CV. And the network has given birth to the (*shudder*) LinkedIn influencer. Younger users poke fun at the kind of content that clogs LinkedIn’s newsfeed; some Gen Zs hilariously troll LinkedIn with satirical posts. They proudly announce their new job at The Krusty Krab Restaurant, a “prestigious establishment” that will offer “a new chapter in [their] life.”

Or they announce their new status as the CEO of a billion-dollar company.

Gen Zs view LinkedIn as a cringeworthy, out-of-touch place for older internet users to subtly (or not-so-subtly) humblebrag. And for nearly as long as LinkedIn has been around, people have been predicting its disruption. But it turns out that LinkedIn has uniquely strong network effects, with millions of job-seekers and recruiters building their professional bedrock with the site. No matter how much cringey influencer content clogs our newsfeeds—and no matter how often LinkedIn prompts us to congratulate a connection on their work anniversary (has anyone ever done that?)—LinkedIn remains a staple of white-collar work.

There are still, of course, modern-day LinkedIn “disruptors” that also build on Pride. Polywork, for example, is a professional network founded on the premise that work is disaggregating, and that we all have more than one way to earn income and express professional identity.

And there are other examples of Pride beyond work—particularly companies that allow users to showcase achievements or make a “flex” in their profile. Discord offers Badges that denote that you’re a paying subscriber to Nitro, or that you’ve been a member of a community for a certain period of time.

But there’s one social network that is deceptively reliant on Pride: Strava. Strava lets athletes show off how far they biked or how far they ran. (Or, in certain cases, the cool shapes they drew with their biking or running route.)

The social features on Strava both keep people accountable and create a powerful mechanism for frequent engagement. Strava leverages Pride in a healthy way—to encourage people to exercise longer and more often.

Strava is Pride.

🦥 Sloth

No company has better captured Sloth in the past decade than Netflix. Netflix turned a Saturday afternoon outing to the multiplex into a 20-foot journey to the couch, while ushering in “peak TV” (600+ scripted shows a year and counting).

Netflix tacitly admits its slothdom when it asks you if you’re still watching after you haven’t touched the mouse / remote in a while. (You are always still watching, and you hit “continue” to carry on watching while feeling just a little bit worse about yourself.)

There are many other examples of Sloth: hiring someone on TaskRabbit to assemble your IKEA furniture; turning to Instacart for getting your groceries; becoming so accustomed to Amazon’s speed that even a two-day delivery begins to feel unacceptable. I’m guilty of all three.

But the sector that best captures Sloth in 2022 is gaming. Gaming is a larger industry than fellow Sloth industries like movies and TV combined. And the premise of the metaverse is inherently sloth-like: our bodies remain motionless in the analog world while our minds explore virtual worlds. I recently wrote about the rise of hypercasual games—games with ultrasimple gameplay. For example, Fill the Fridge (stocking a fridge) or Acrylic Nails (painting nails). Why fill the fridge in real life when your fingers can fill a virtual fridge on your iPhone?

Hypercasual game downloads surged to 15.6 billion last year, up from 12.6 billion in 2020 and 7.5 billion in 2019. Fill the Fridge is made by Rollic, a hypercasual game studio that Zynga just bought a stake in. Fittingly, 11 years ago, Zynga was Hoffman’s example for Sloth.

💍 Envy

Comparison is the root of Envy, and social media is built on comparison. I’ve pointed before to Olivia Rodrigo’s lyrics to “Jealousy, Jealousy”:

I kinda wanna throw my phone across the room

’Cause all I see are girls too good to be true

With paper-white teeth and perfect bodies

Wish I didn’t careComparison is killin’ me slowly

Instagram began as a literal filtered version of reality.

Envy feeds engagement. Younger social media users, who grew up online, are rejecting that premise. Rodrigo, for example, posted the following Instagram caption in April 2020:

today I took the classic Instagram dive, comparing myself to girls incessantly and wishing I had what they looked like they had. it’s so silly how we/i define ourselves by the most arbitrary things and idolize ppl who are humans just like us. anyway, i wrote this song today about the tendency I have to go down this self sabotaging hole and now I’m posting it on Instagram because I love irony. if ur reading this pls know that ur value is so inherent. it’s not something that could ever be defined by something as contrived and manipulative as social media. you are so loved!

Instagram disruptors like BeReal, Poparazzi, Dispo, and Locket have promised a more authentic, less curated reality. But even authenticity, over time, becomes performative; “photo dumps” become carefully-crafted compilations of artsy images that show us in a good light (“Look how this blurry photo implies I’m too busy having fun to take non-blurry pictures!”)

What’s a 2022 company built on Envy? The NFT hype of the past 18 months was derived from FOMO (fear of missing out), a close cousin of Envy. People who bought expensive digital assets wanted a place to show those off, turning to places like the virtual world of Decentraland. Here’s an NFT art gallery in Decentraland:

Even Sotheby’s opened an art gallery in Decentraland, while Snoop Dogg (never one to be left out on a tech craze) laid his roots in the competing virtual platform The Sandbox. (Someone then paid $450K to be Snoop’s neighbor in The Sandbox.)

Crypto wallets and virtual showrooms like Decentraland are the best modern example of Envy. Envy and Greed go hand-in-hand, which leads us to…

💰 Greed

A decade ago, Greed was signified by the rise of investing apps. Coinbase let us buy and sell crypto, minting thousands of Bitcoin millionaires. Fast forward to 2021, and 48% of Americans invested in crypto, with 63% saying the primary reason for doing so was to make money.

Today, everything is investable. We can invest in sports cards with Alt. We can invest in fine art with Masterworks. We can invest in people with Rally and we can invest in collectibles with a different startup called Rally. Everything is being financialized.

But the best example for Greed is cryptomania. What else explains why JPEGs of unenthused apes are selling for $100K—even after a 75% loss in value.

The company underpinning this new economy is OpenSea. Some portion of buyers on OpenSea are buying because they want to support an artist, because they want to belong to a community, or because they want to see what the NFT hype is all about. But most are buying because they hope to make (lots of) money. Who can blame them, with the media focused on the stories of people who got rich trading crypto assets? Greed is a powerful motivator.

🤤 Gluttony

When Reid Hoffman mentioned the seven deadly sins 11 years ago, he used GrubHub as the example for Gluttony. A lot has happened since then. In 2013, GrubHub merged with Seamless. In 2021, GrubHub completed its sale to Just Eat Takeaway.com.

Amidst all the changing of hands, the company’s market share stagnated. DoorDash, meanwhile, cemented itself as the clear leader in America’s food delivery wars. You could make the argument that DoorDash now represents Gluttony.

But there are new food startups making it even easier and cheaper and more enjoyable for people to eat. Though DoorDash has swelled to a $30 billion market cap (down from about $100 billion at its peak last November), food delivery is only ~10% of the restaurant market; takeout, meanwhile, makes up ~90%.

Snackpass is a social takeout app that lets you order ahead and pick up food—sort of like the Starbucks app, but for every restaurant. Snackpass gamifies food by letting you earn reward points and then gift free things to friends (for example, you can send your crush a boba tea 🧋 ).

Restaurants are a near-trillion-dollar market in the U.S.; our entire food industry is built on Gluttony. Companies like Snackpass are ushering in the next generation of more social and frictionless eating.

💄 Lust

Tinder is the canonical example of Lust. The company built its name on looks-based dating, with rapid swiping based only on a photo. A new onslaught of dating apps, many owned by Tinder’s parent company Match Group, are working to make online dating less visual. (Hinge, in particular, is having a moment.) But Tinder continues to be king of dating, perpetually near the top of the highest-grossing apps chart.

Even the highest-grossing games and streaming services can’t compete with Tinder, which now counts 6.6 million paid subscribers.

Dating and chat apps are still the best examples of Lust-based networks. It turns out that Lust makes for a great business. Grindr, the gay chat app, averages 61 minutes of engagement every day—equivalent to Facebook and Instagram combined. (Tinder is about 15 minutes.) This is because Grindr is typically used as more of a hook-up app, with live geolocation (“so-and-so is 12 feet away”). As the old maxim says, sex sells: Grindr did $150 million in revenue last year, with $16 in ARPU (average revenue per user) to Tinder’s $13.

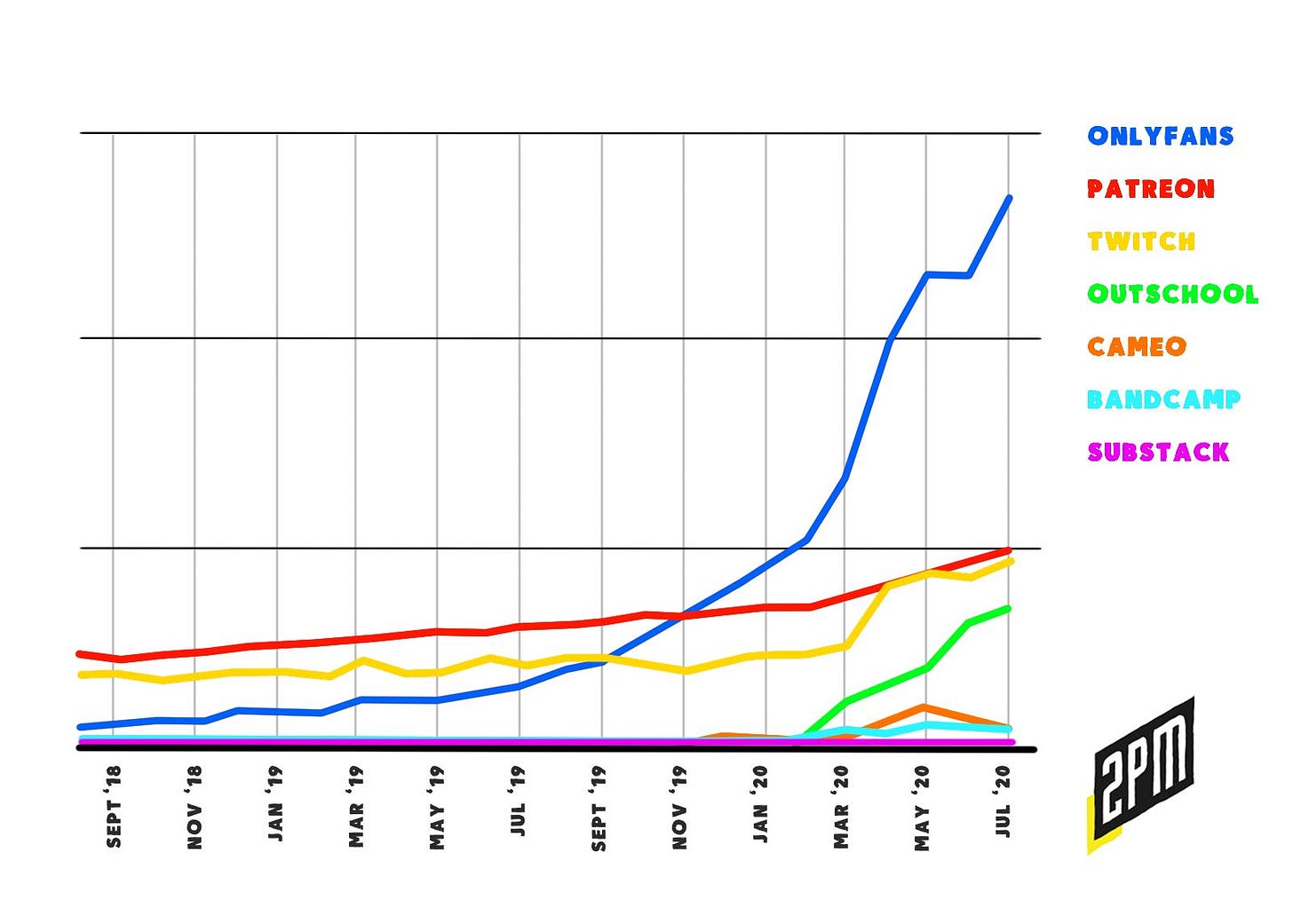

But beyond dating apps, there’s a new entrant in Lust: OnlyFans. OnlyFans exploded during the pandemic by cutting out the middleman of pornography, allowing creators to directly share content (usually NSFW) with their subscribers.

I like how my friend Lucy puts it:

“OnlyFans commoditized intimacy. It’s a tale as old as time—people are willing to pay for things they need, and they need intimacy and connection now more than ever. It seems capitalism slowly works its way up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and we’ve hit the Love & Belonging rung of the ladder with dating apps, paid communities, and fan subscription services.

Sex sells. Lust sells. And Lust is powering one of the most successful creator platforms.

😡 Wrath

In The Atlantic, Robinson Meyer wrote:

Wrath, according to Dante, was a twin sin to sullenness. He wrote that they both came from the same essential error: Wrath is rage expressed, sullenness is rage unexpressed. And he condemned both the sullen and the wrathful to the Fifth Circle—where, in a foul marsh, the wrathful attacked each other unendingly, without ever winning, while the sullen sat beneath the murk and stewed and scowled and acted aloof. Rarely has there been a better description of Twitter.

Twitter has always been about Wrath. Everyone on Twitter always seems…angry. Rather than adhering by “Strong opinions, weakly held”, power users seem to have strong opinions strongly held, and 280 characters doesn’t leave much room for nuance or thoughtful debate.

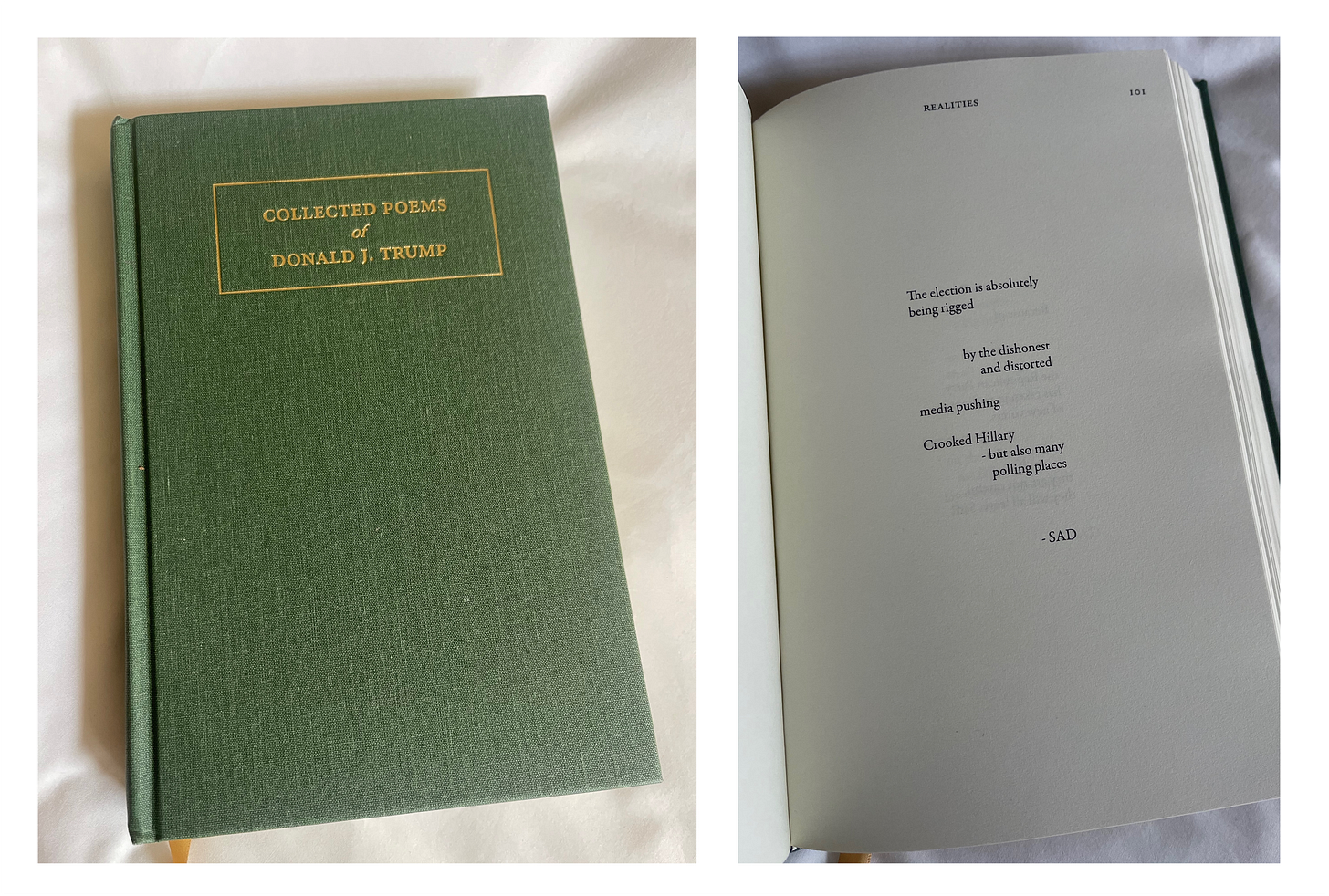

When I think of Twitter personified, I think of Donald Trump. I think of the excellent book Collected Poems of Donald J. Trump, which I proudly own. (Highly recommend it as a gift.)

Pure poetry.

Twitter is undoubtedly still Wrath, though Wrath is perhaps even better embodied by far-right social platforms like Parler and Gab (though you could argue that their lack of liberals makes people more homogenous and thus less angry). Review-based apps like Yelp also rely heavily on Wrath; some people even lose their jobs for being overly angry on Yelp. Fox News, meanwhile, has turned Wrath into its entire business model.

But another more subtle example is a startup that cleverly channels Wrath in a productive way. DoNotPay offers you a “robot lawyer” that lets you sue anyone at the press of a button. Think of all the things that make you really, really mad—lawsuit mad. Parking tickets. Malicious landlords. Identity theft. Airline cancellations. Insurance claims. DoNotPay has built a surprisingly large business on helping you solve all of them.

The company promises to “fight corporations” and “beat bureaucracy”, redirecting Wrath to bring about positive outcomes.

Final Thoughts

Theologians often recognize two other sins, beyond the initial seven.

The first is Vanity, which has close ties to Envy. Instagram (and any social network, particularly visual-based social networks) could also be attributed to Vanity. Though perhaps the best example of Vanity is Lightricks, the maker of the editing app Facetune. What Facetune did is allow anyone to harness the power of professional-grade photoshopping, a decades-old practice in advertising and magazines, all from a smartphone. Facetune used a freemium model to become Apple’s most-popular paid app in 2017, charging users $5.99 / month to unlock premium features. In 2018, Facetune was downloaded 20 million times and had 500,000 paying users.

Facetune leaned into social media’s distortion of reality; here’s an image Lightricks uses to promote Facetune:

“Facetune face” quickly became a meme.

Facetune’s success was built on our natural human desire to look good—our Vanity—nurtured by our image-obsessed culture.

The second additional sin—“the 9th sin”—is Acedia, a word which has faded from our vocabulary. Acedia is effectively apathy or listlessness, “not caring or not being concerned with one's position or condition in the world.” It’s the sin which I think most succinctly sums up Gen Z nihilism. Acedia is evident in the gallows humor, the 💀 emojis, the antiwork movement. It’s evident in the Birds Aren’t Real movement, an absurdist conspiracy theory disguising a cry for help. (Spoiler: members of the movement know that birds are, in fact, real.)

The seven nine deadly sins are evident in how we use technology every day, and in how we interact with each other through online networks. Companies are built on consumer behavior and consumer behavior, in turn, is built on our most fundamental, unchanging vices.

Sources & Additional Reading

Robinson Meyer in The Atlantic (2016)

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: